NEW YORK (AP) — Prosecutors and defense lawyers agree on this about Marine veteran Daniel Penny's encounter last year with a distressed, angry man making ominous remarks on a New York subway: Penny didn't mean to kill him.

But a prosecutor told jurors Friday that Penny “went way too far” in trying to neutralize someone he saw as a threat and not as a person. A defense attorney countered that Penny showed “courage" and put others' welfare ahead of his own when he placed Jordan Neely in a chokehold that ended with Neely limp on the floor.

Click to Gallery

In this image from body camera video provided by New York City Police Department, emergency medical personnel in a New York City subway car attempt to revive Jordan Neely after he was placed in a chokehold by Daniel Penny on May 5, 2023. (New York City Police Department via AP)

Daniel Penny, accused of choking a distressed Black subway rider to death, arrives for opening statements in New York, Friday, Nov. 1, 2024.(AP Photo/Kena Betancur)

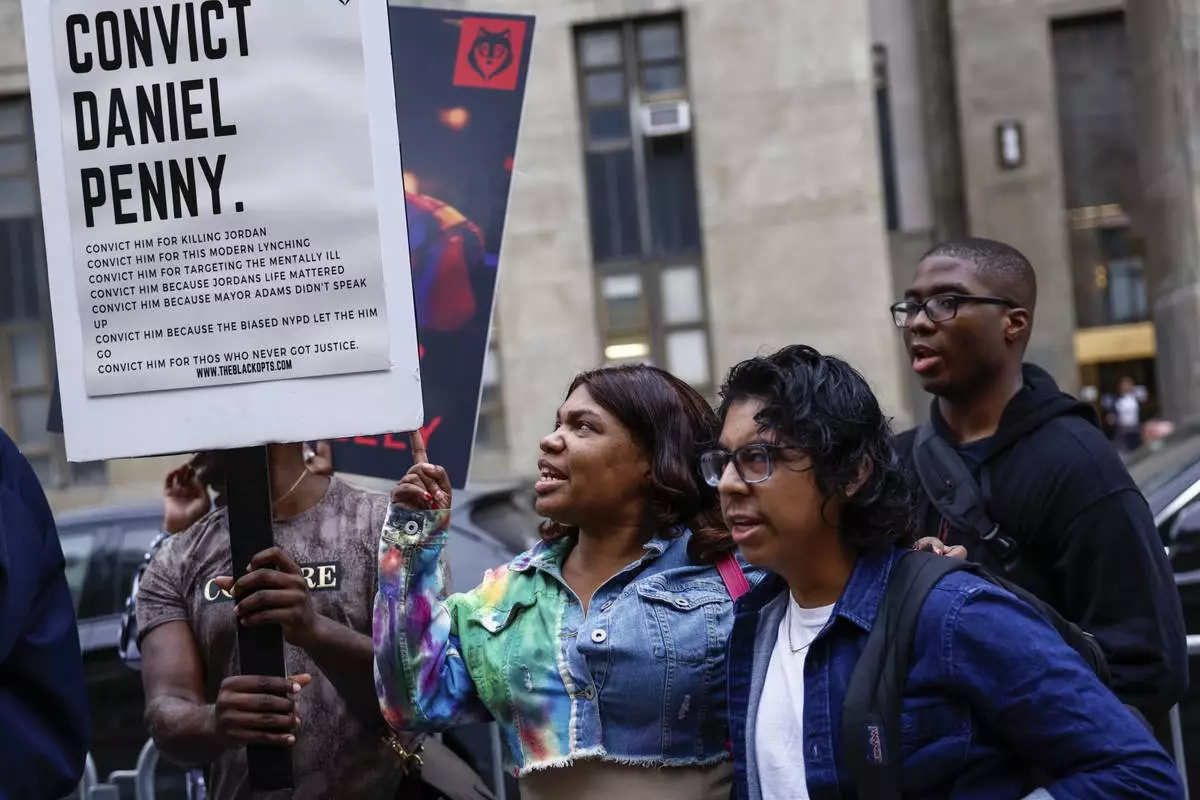

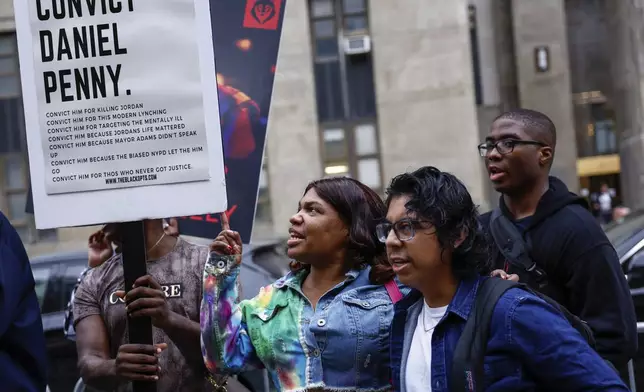

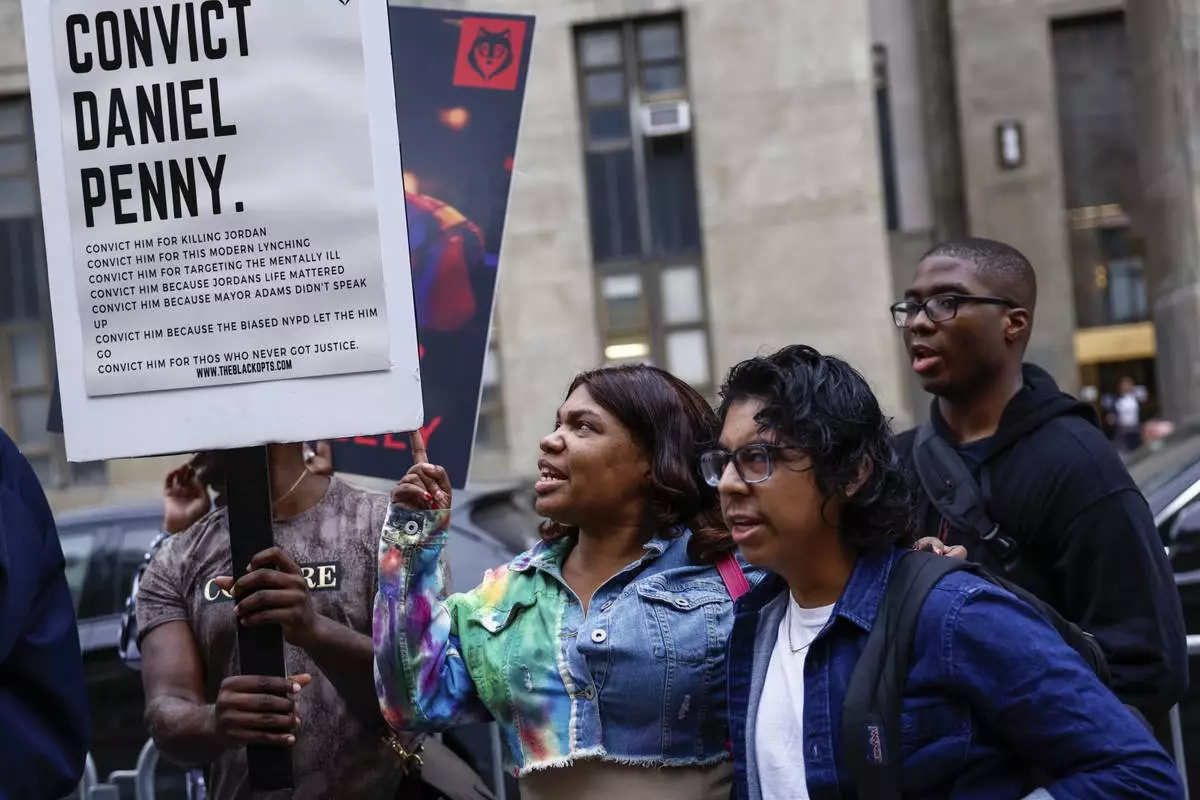

Protestors gather before Daniel Penny, the white veteran accused of choking a distressed Black subway rider to death, arrives for opening statements at the court in New York, Friday, Nov. 1, 2024.(AP Photo/Kena Betancur)

A Protestor speaks before Daniel Penny, the white veteran accused of choking a distressed Black subway rider to death, arrives for opening statements at the court in New York, Friday, Nov. 1, 2024.(AP Photo/Kena Betancur)

Daniel Penny, accused of choking a distressed Black subway rider to death, arrives for opening statements in New York, Friday, Nov. 1, 2024.(AP Photo/Kena Betancur)

Daniel Penny, accused of choking a distressed Black subway rider to death, arrives for opening statements in New York, Friday, Nov. 1, 2024.(AP Photo/Kena Betancur)

Protestors gather before Daniel Penny, the white veteran accused of choking a distressed Black subway rider to death, arrives for opening statements at the court in New York, Friday, Nov. 1, 2024.(AP Photo/Kena Betancur)

Daniel Penny, accused of choking a distressed Black subway rider to death, arrives for opening statements in New York, Friday, Nov. 1, 2024.(AP Photo/Kena Betancur)

This image from body camera video provided by New York City Police Department, Penny, standing at left, looks on in a New York City subway car as officers attempt to revive Jordan Neely onMay 5, 2023. (New York City Police Department via AP)

Daniel Penny, accused of choking a distressed Black subway rider to death, arrives for opening statements in New York, Friday, Nov. 1, 2024.(AP Photo/Kena Betancur)

A group of people rally in support of justice for Jordan Neely across the street from the Manhattan criminal courts in New York, Monday, Oct. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

Daniel Penny returns to the courtroom after a break in New York, Monday, Oct. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

Both sides gave opening statements Friday in a manslaughter trial that has rattled fault lines surrounding race, homelessness, perceptions of public safety and bystanders’ responsibility.

Penny’s critics see him as a white vigilante killer of a Black man who was behaving erratically and making dire statements but wasn’t armed and hadn’t assaulted or even touched anyone in the subway car. Supporters credit the 25-year-old Penny with taking action to protect frightened riders — action that he has said was meant to defuse, not kill.

Prosecutor Dafna Yoran told the anonymous jury that the trial isn’t “a referendum on our society’s failure to deal with mental illness and homelessness on the subway" or on police response. Nor is the case about whether Penny had a right to intervene or about his decision to try a chokehold, she said.

Rather, she said, “He used far too much force for far too long. He went way too far.”

She said he showed “indifference” toward Neely and “didn’t recognize his humanity.”

Not so, said defense lawyer Thomas Kenniff. He told jurors that Penny applied only as much force as needed to contain a “seething, psychotic” man who had lunged toward a woman with a small child and declared, “I will kill.”

“In that moment, Danny could look away and pray, or he could summon the courage to put the safety of his neighbors above that of himself, to protect those who could not protect themselves,” and he did the latter, Kenniff said.

“It doesn’t make him a hero. But it doesn’t make him a killer.”

Jurors, who were quizzed earlier about their subway experiences, later saw police body camera video of officers performing some lifesaving techniques on Neely after Penny calmly explained he had “put him out," describing Neely as a “crackhead” who was “going crazy.”

The case has been absorbed into the United States’ fractious politics, with Republican officials speaking up for Penny and Democratic ones attending Neely’s funeral. Both supporters and critics of Penny have held demonstrations; Penny arrived at the courthouse Friday to critical chants from a small group of protesters.

Once in court, Penny sat straight up in his seat at the defense table, mostly looking directly ahead. A member of Neely's family who was in the audience sometimes sniffled with tears.

“We know who the victim is in this case, and we know who the villain is," family lawyer Donte Mills said outside court.

Neely's life was tattered by mental illness and drug use after his mother was murdered and stuffed in a suitcase when he was a teen, his family has said. By 30, he sometimes entertained subway riders as a Michael Jackson impersonator, but he also had a criminal record that included assaulting a woman at a subway station.

Penny, an architecture student who served four years in the Marines, was going from class to a gym when he encountered Neely on a subway May 1, 2023.

Neely was begging for money, shouting about being willing to die or go to jail, and making sudden movements, according to witnesses. Yoran said Neely talked about hurting people.

Penny put his arm around the man's neck, took him to the floor and held Neely there, with Penny's legs around him.

With bystanders recording some of the encounter on video, Penny held Neely for about six minutes, Yoran said. The hold continued as the train stopped at a station, all but two fellow riders got off, those two helped restrain Neely, and another warned Penny to let Neely go or he'd die, according to Yoran's statement and court papers.

Kenniff said Penny pleaded with fellow passengers to call police and that he kept holding Neely because the man periodically flailed or tried to get up.

Penny ultimately released Neely nearly a minute after his body went limp, prosecutors said. He waited for police, but Yoran noted that despite being trained in first aid, Penny didn’t check Neely’s breathing or pulse or try to revive him.

Officers arrived about seven minutes after 911 calls started coming in, their description as varied as harassment and a gun-toting man.

Over about four minutes, officers talked to Penny, searched Neely — finding nothing but a muffin in his pockets — and determined he had a faint pulse but wasn't breathing. Then they did chest compressions and administered an overdose-reversal drug but didn’t attempt mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

Asked why, Sgt. Carl Johnson testified Friday that Neely was “very dirty,” and the sergeant feared the man might have a disease or wake up and vomit.

“The motto is ‘serve and protect,’ right?” Kenniff said. He asked whether Johnson would have ordered rescue breaths if the officers had a protective mask.

“No,” Johnson replied, adding: “There’s a certain line where you have to protect your officers."

Neely's pulse soon faded away.

Penny told police that he had simply wanted to “de-escalate” the edgy situation and wasn’t trying to injure Neely but rather "to keep him from hurting anyone else.”

City medical examiners determined Neely died from compression of the neck. Penny’s lawyers question that finding.

Associated Press journalists Joseph Frederick and David R. Martin contributed.

In this image from body camera video provided by New York City Police Department, emergency medical personnel in a New York City subway car attempt to revive Jordan Neely after he was placed in a chokehold by Daniel Penny on May 5, 2023. (New York City Police Department via AP)

Daniel Penny, accused of choking a distressed Black subway rider to death, arrives for opening statements in New York, Friday, Nov. 1, 2024.(AP Photo/Kena Betancur)

Protestors gather before Daniel Penny, the white veteran accused of choking a distressed Black subway rider to death, arrives for opening statements at the court in New York, Friday, Nov. 1, 2024.(AP Photo/Kena Betancur)

A Protestor speaks before Daniel Penny, the white veteran accused of choking a distressed Black subway rider to death, arrives for opening statements at the court in New York, Friday, Nov. 1, 2024.(AP Photo/Kena Betancur)

Daniel Penny, accused of choking a distressed Black subway rider to death, arrives for opening statements in New York, Friday, Nov. 1, 2024.(AP Photo/Kena Betancur)

Daniel Penny, accused of choking a distressed Black subway rider to death, arrives for opening statements in New York, Friday, Nov. 1, 2024.(AP Photo/Kena Betancur)

Protestors gather before Daniel Penny, the white veteran accused of choking a distressed Black subway rider to death, arrives for opening statements at the court in New York, Friday, Nov. 1, 2024.(AP Photo/Kena Betancur)

Daniel Penny, accused of choking a distressed Black subway rider to death, arrives for opening statements in New York, Friday, Nov. 1, 2024.(AP Photo/Kena Betancur)

This image from body camera video provided by New York City Police Department, Penny, standing at left, looks on in a New York City subway car as officers attempt to revive Jordan Neely onMay 5, 2023. (New York City Police Department via AP)

Daniel Penny, accused of choking a distressed Black subway rider to death, arrives for opening statements in New York, Friday, Nov. 1, 2024.(AP Photo/Kena Betancur)

A group of people rally in support of justice for Jordan Neely across the street from the Manhattan criminal courts in New York, Monday, Oct. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

Daniel Penny returns to the courtroom after a break in New York, Monday, Oct. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

COLUMBIA, S.C. (AP) — South Carolina put Richard Moore to death by lethal injection Friday for the 1999 fatal shooting of a convenience store clerk, despite a broad appeal for mercy by parties that included three jurors and the judge from his trial, a former prison director, pastors and the his family.

Moore, 59, was pronounced dead at 6:24 p.m.

Moore was convicted of killing the Spartanburg convivence store clerk in September 1999 and sentenced to death two years later. Moore went into the store unarmed, took a gun from the victim when it was pointed at him and fatally shot him in the chest as the victim shot him with a second gun in the arm.

Moore’s lawyers asked Republican Gov. Henry McMaster to reduce his sentence to life in prison without parole because of his spotless prison record and willingness to be a mentor to other inmates. They also said it would be unjust to execute someone for what could be considered self-defense and unfair that Moore, who is Black, was the only inmate on the state’s death row convicted by a jury without any African Americans.

But McMaster refused to grant clemency. No South Carolina governor has reduced a death sentence, and 45 executions have now been carried out since the U.S. Supreme Court allowed states to restart executions nearly 50 years ago.

Unlike in previous executions, the curtain to the death chamber was open when media witnesses arrived. Moore's last words had already been read by Lindsey Vann, his lawyer of 10 years.

Moore had his eyes closed and his head was pointed toward the ceiling. A prison employee announced the execution could begin at 6:01 p.m. Moore took several deep breaths that sounded like snores over the next minute. Then he took some shallow breaths until about 6:04, when his breathing stopped. Moore showed no obvious signs of discomfort.

Vann cried as the employee announced the execution could start. She clutched a prayer bracelet with a cross. Sitting beside her was a spiritual advisor, his hands on his knees palms up. Vann clutched a prayer bracelet with a cross.

Two members of the victims' family were also present, along with Solicitor Barry Barnette, who was on the prosecution team that convicted Moore. They all watched stoically.

Afterward prison spokeswoman Chrysti Shain read his last words at a news conference.

“To the family of Mr. James Mahoney, I am deeply sorry for the pain and sorrow I caused you all,” he said. “To my children and granddaughters, I love you and am so proud of you. Thank you for the joy you have brought to my life. To all of my family and friends, new and old, thank you for your love and support.”

His final meal was steak cooked medium, fried catfish and shrimp, scalloped potatoes, green peas, broccoli with cheese, sweet potato pie, German chocolate cake and grape juice.

Three jurors who condemned Moore to death in 2001, including one who wrote Friday, sent letters asking McMaster to change his sentence to life without parole. They were joined by a former state prison director, Moore's trial judge, his son and daughter, a half-dozen childhood friends and several pastors.

They all said Moore, 59, was a changed man who loved God, doted on his new grandchildren the best he could, helped guards keep the peace and mentored other prisoners after his addiction to drugs clouded his judgment and led to the shootout in which James Mahoney was killed, according to the clemency petition.

Moore previously had two execution dates postponed as the state sorted through issues that created a 13-year pause in the death penalty, including companies' refusal to sell the state lethal injection drugs, a hurdle that was solved by passing a secrecy law.

Moore is the second inmate executed in South Carolina since it resumed executions. Four more are out of appeals and the state appears ready to put them to death in five-week intervals through the spring. There are now 30 people on death row.

The governor said before the execution that he would carefully reviewing everything sent by Moore's lawyers and, as is customary, would wait until minutes before the execution starts to announce his decision once he hears by phone that all appeals are finished.

“Clemency is a matter of grace, a matter of mercy. There is no standard. There is no real law on it,” McMaster told reporters Thursday.

In an interview for a video that accompanied his clemency petition, Moore expressed remorse for the killing of Mahoney.

“This is definitely part of my life I wish I could change. I took a life. I took someone’s life. I broke the family of the deceased,” Moore said. “I pray for the forgiveness of that particular family.”

Prosecutors and Mahoney's relatives have not spoken publicly in the weeks leading up to the execution. In the past, family members have said they suffered deeply and want justice to be served.

Moore’s lawyers said his original attorneys did not analyze the crime scene carefully and left unchallenged prosecutors' contention that Moore, who came into the store unarmed, fired at a customer and that his intention from the start was a robbery.

According to their account, the clerk pulled a gun on Moore after the two argued because he was 12 cents short for what he wanted to buy.

Moore said he wrestled the gun from Mahoney's hand and the clerk pulled a second weapon. Moore was shot in the arm and fired back, hitting Mahoney in the chest. Moore then went behind the counter and stole about $1,400.

No one else on South Carolina’s death row started their crime unarmed and with no intention to kill, Moore’s current attorneys say.

Jon Ozmint, a former prosecutor who was director of the South Carolina Department of Corrections from 2003 to 2011 and who added his voice to those seeking clemency, said Moore's case was not the worst-of-the-worst kind of crime that would usually prompt a death penalty case.

There are plenty of people who were not sentenced to death but committed much more heinous crimes, Ozmint said, citing the example of Todd Kohlhepp, who was given a life sentence after pleading guilty to killing seven people including a woman he raped and tortured for days.

Lawyers for Moore, who is Black, also said his trial was not fair. There were no African Americans on the jury even though 20% of Spartanburg County residents were Black.

Moore’s son and daughter said he remained engaged in their lives. He once asked them about schoolwork and gave advice in letters. He now had grandchildren whom he saw on video calls.

“Even though my father has been away, that still has not stopped him from making a big impact on my life, a positive impact,” said Alexandria Moore, who joined the Air Force at her father’s encouragement.

This undated photo provided by the South Carolina Department of Corrections shows the execution room at the Broad River Correctional Institution in Columbia, S.C. (South Carolina Department of Corrections via AP)

This undated photo provided by the South Carolina Department of Corrections shows the witness room in the execution chamber at the Broad River Correctional Institution in Columbia, S.C. (South Carolina Department of Corrections via AP)

This photo provided by Justice 360 shows death row inmate Richard Moore at Kirkland Reception and Evaluation Center in Columbia, S.C., Aug. 17, 2018. (Justice 360 via AP)