CHISINAU, Moldova (AP) — Moldovan historian and politician Octavian Ticu remembers when the Soviet Union collapsed in the early 1990s, a seismic event that enabled him to become one of the first amateur boxers to fight for his country at the pinnacle of his sport: the Olympic Games.

“It was a happy moment for me,” the 52-year-old recalls, as he wraps his fists at a boxing gym in the capital, Chisinau. “In 1996, I participated in the Olympics in Atlanta. … If I were in the Soviet Union, I would never have accomplished this.”

But today, more than three decades after proclaiming independence, Moldova is being targeted by Russia in a hybrid war of propaganda and disinformation that “wreaks havoc,” Ticu, who competed in the lightweight division, told The Associated Press.

Like Ukraine and Georgia, the former Soviet republic aspires to join the European Union but is caught in a constant geopolitical tug between Moscow and the West.

“Russian propaganda is a reality of 30 years of independence,” added Ticu, who has written several books on his country’s history.

This story, supported by the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting, is part of an ongoing Associated Press series covering threats to democracy in Europe.

In a national referendum on Oct. 20, Moldovans voted by a razor-thin majority of 50.35% in favor of securing a path toward EU membership. But the result was overshadowed by allegations of a Moscow-backed vote-buying scheme.

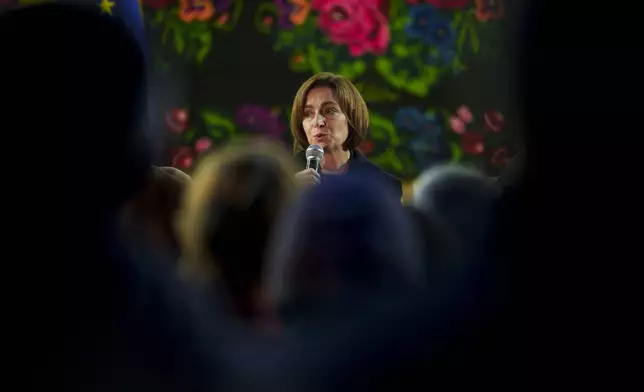

In a presidential election held the same day, incumbent pro-Western President Maia Sandu obtained 42% of the vote, but failed to win an outright majority. On Sunday, she will face Alexandr Stoianoglo, a Russia-friendly former prosecutor general, in a runoff viewed as a choice between geopolitical opposites — again.

As in the EU referendum, a poll released this week by research company iData indicates a tight race on Sunday that leans toward a narrow Sandu victory, an outcome that might rely on Moldova's large diaspora.

The presidential role carries significant powers in areas such as foreign policy and national security.

In the wake of the two October votes, Moldovan law enforcement said that a vote-buying scheme was orchestrated by Ilan Shor, an exiled oligarch who currently lives in Russia and was convicted in absentia in 2023 of fraud and money laundering. Prosecutors say $39 million was paid to more than 130,000 recipients through an internationally sanctioned Russian bank to voters between September and October. Shor denies any wrongdoing.

“These people who go to Moscow, the so-called government-in-exile of Ilan Shor, who come with very large sums of money, are left to roam free,” said Ticu, who ran as a long-shot candidate in the presidential race.

It was “obvious,” Ticu added, that the votes would “not be fair or democratic.” Of the 11 first-round candidates, he was the only one to endorse Sandu in the runoff.

Voters from Moldova’s Kremlin-friendly breakaway region of Transnistria, which declared independence after a short war in the early 1990s, can cast ballots in Moldova proper. Transnistria has been a source of tension during the war in neighboring Ukraine, especially since it is home to a military base with 1,500 Russian troops.

Ticu warned that if Russian troops in Ukraine reach the port city of Odesa, they could “join the Transnistrian region, and then the Republic of Moldova will be occupied."

In Gagauzia, an autonomous part of Moldova where only 5% voted in favor of the EU, a doctor was detained after allegedly coercing 25 residents of a home for older adults to vote for a candidate they did not choose. Police said they obtained “conclusive evidence,” including financial transfers from the same sanctioned Russian bank.

Anticorruption authorities have conducted hundreds of searches and seized over $2.7 million (2.5 million euros) in cash as they attempt to crack down.

On Thursday, prosecutors raided a political party headquarters and said 12 people were suspected of paying voters to select a candidate in the presidential race. A criminal case was also opened in which 40 state agency employees were suspected of taking electoral bribes.

Instead of winning the overwhelming support that Sandu had hoped, the results in both races exposed Moldova’s judiciary as unable to adequately protect the democratic process. It also allowed some pro-Moscow opposition to question the validity of the votes.

Igor Dodon, the Party of Socialists leader and former president who has close ties to Russia, stated this week that “we don’t recognize” the referendum result, and labeled Sandu “a dictator in a skirt” who will “do whatever it takes to stay in power.”

Sandu admitted the ballots suffered from unprecedented fraud and foreign meddling, which undermined the results, calling the interference a “vile attack” on Moldova’s sovereignty.

“If the judiciary does not wake up … if it closes its eyes to selling the country, the future of Moldova will be in danger for decades,” she warned.

Moldova is one of Europe’s poorest countries and has been hit hard by inflation since the war started. Tatiana Cojocari, a Russia foreign policy expert at Chisinau-based think-tank WatchDog, says this means many citizens could “fall prey to electoral corruption” for relatively small amounts of money.

“For Russia, it’s very important to have as many resources as possible to work with. It creates chaos, both informationally and politically,” Cojocari said, adding that Russia "has turned a bit to the tactics of the Cold War and uses them skillfully, only now adapted to social media.”

In the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Moldova applied to join the EU. It was granted candidate status in June of that year, and in summer 2024, Brussels agreed to start membership negotiations. The sharp Westward shift irked Moscow and significantly soured relations with Chisinau.

Since then, Moldovan authorities have repeatedly accused Russia of waging a vast “hybrid war,” from sprawling disinformation campaigns to protests by pro-Russia parties to vote-buying schemes that undermine countrywide elections. Russia has denied it is meddling.

Social media platforms have played a crucial role in disseminating Russian propaganda in Moldova, says Andrei Rusu, a media monitoring expert at WatchDog. “One of the biggest lies is that if Moldovans join the EU, they will go to war with Russia, they will lose their faith and traditional values, or they will be forced to follow LGBT propaganda," he said.

Moldovans who lived through the Soviet Union, he added, can struggle to spot Russian propaganda about the EU and the West, and differentiate between real videos and ones generated by artificial intelligence, such as those that have frequently appeared online depicting Sandu.

In recent weeks, Meta and Telegram removed multiple fake accounts that railed against the EU and Sandu, and that expressed support for pro-Russian parties.

However, Moldova watchers warn that Moscow’s main target could be the 2025 parliamentary elections. Waning support for the governing pro-Western Party of Action and Solidarity suggests it could lose its majority in the 101-seat legislature.

“We are already waiting for the parliamentary elections to see other tactics and strategies,” added Cojocari, the Russia analyst. “This government will no longer be able … to secure a parliamentary majority.”

Back at the boxing gym, Ticu warned more must be done to counter foreign interference, or face a “danger of hybrid governance” with pro-Russian forces.

“Very good laws have been adopted, but are not implemented,” he said. Russian President Vladimir “Putin does not want a war in Moldova, he wants to show the world and Europe a case in which European integration policies have failed.”

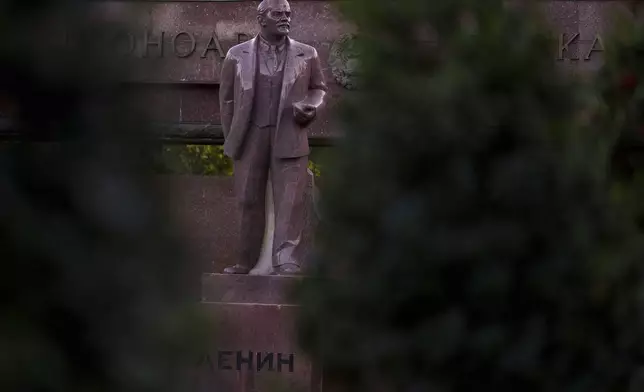

Children skate next to a statue of Lenin, with the words "Board of Honor" written in Cyrillic in Romanian and Russian in Chisinau, Moldova, Friday, Nov. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Vadim Ghirda)

FILE - Moldova's President Maia Sandu speaks to people in Magdacesti, Moldova, Oct. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Vadim Ghirda, File)

Moldovan historian and politician Octavian Ticu, right, trains with coach Igor Rotaru, in a gym in Chisinau, Moldova, Oct. 18, 2024. (AP Photo/Vadim Ghirda)

FILE - A woman mops a stage before an electoral rally of Moldova's President Maia Sandu in Magdacesti, Moldova, Oct. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Vadim Ghirda, File)

Tatiana Cojocari, a Russia foreign policy expert at WatchDog, a Chisinau-based think-tank speaks during an interview with the Associated Press in Chisinau, Moldova, Oct. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Vadim Ghirda)

A statue of Lenin, with the words "Board of Honor" written in Cyrillic in Romanian and Russian in Chisinau, Moldova, Friday, Nov. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Vadim Ghirda)

Moldovan historian and politician Octavian Ticu speaks during an interview with the Associated Press in a gym in Chisinau, Moldova, Oct. 18, 2024. (AP Photo/Vadim Ghirda)

A woman walks past posters displaying Alexandr Stoianoglo, presidential candidate of the Socialists' Party of Moldova (PSRM) in Chisinau, Moldova, Friday Nov. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Vadim Ghirda)

Alexandr Stoianoglo, presidential candidate of the Socialists' Party of Moldova (PSRM) delivers a statement at the party headquarters in Chisinau, Moldova, Oct. 18, 2024. (AP Photo/Vadim Ghirda)

FILE - A woman walks by a depiction of the European Union flag near a park in central Chisinau, Moldova, Oct. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Vadim Ghirda, File)

Moldovan historian and politician Octavian Ticu trains in a gym in Chisinau, Moldova, Oct. 18, 2024. (AP Photo/Vadim Ghirda)

A girl skates next to a statue of Lenin, with the words "Board of Honor" written in Cyrillic in Romanian and Russian in Chisinau, Moldova, Friday, Nov. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Vadim Ghirda)