HONG KONG (AP) — A former Hong Kong reporter of The Wall Street Journal on Tuesday said she'll sue the publication for sacking her because she joined a trade union.

Selina Cheng lost her job in July after a senior editor told her that her position was eliminated due to restructuring. However, Cheng believed the termination was linked to her refusal to comply with her supervisor’s request to withdraw from the election for the chairperson of the Hong Kong Journalists Association, a trade union for journalists that advocates for press freedom.

Cheng, now the chair of the association, said in a press briefing that she had sought mediation with her former employer through private channels and legal representatives, but their communication was “not fruitful" and her former employer refused to reinstate her job.

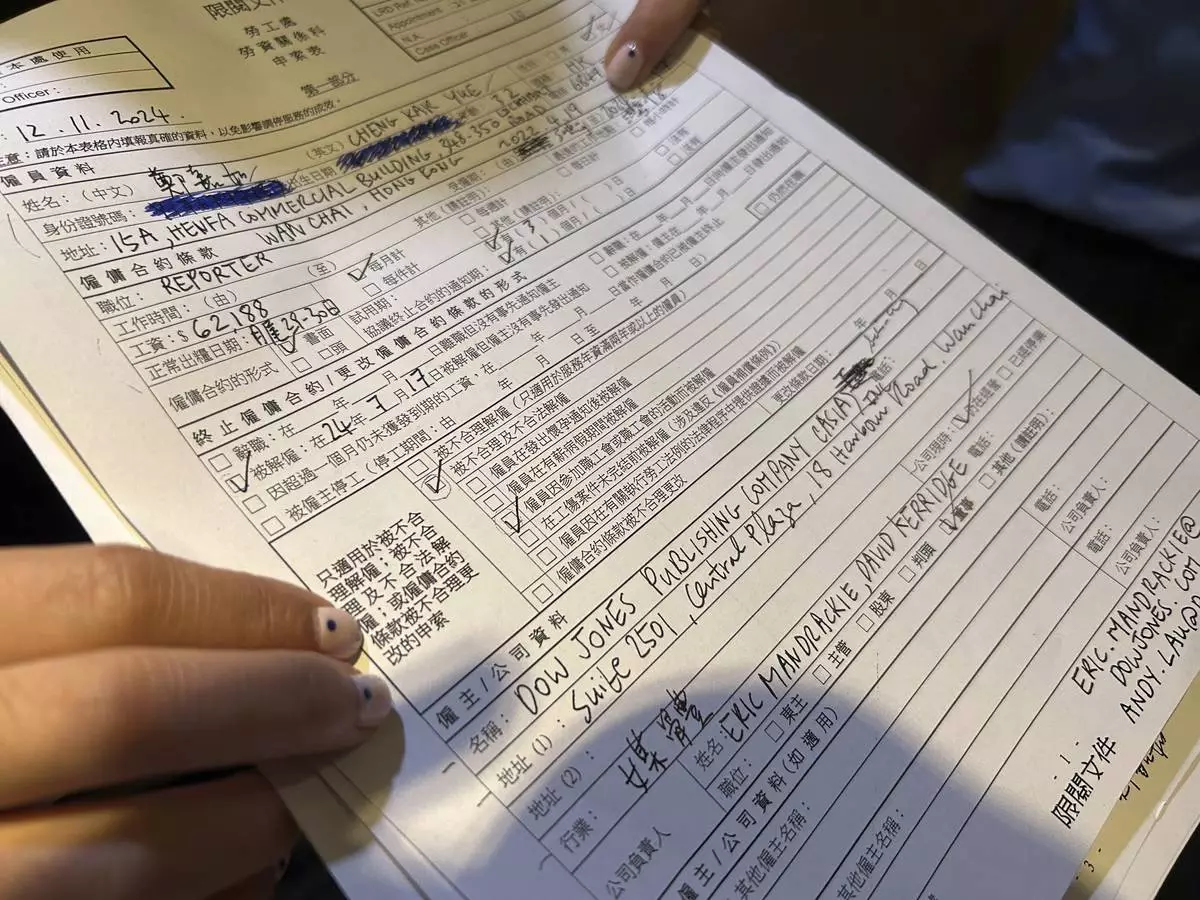

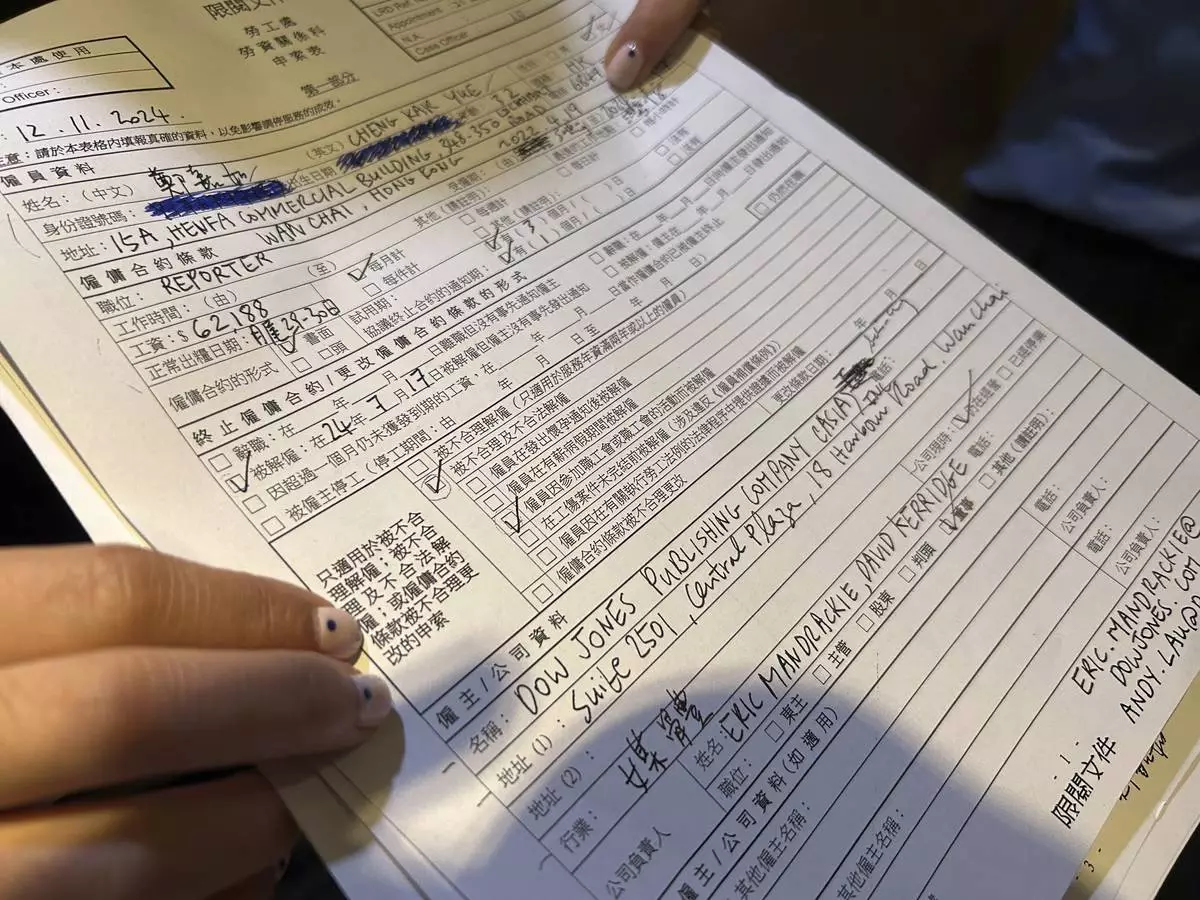

After the failed attempts, Cheng said she would file a civil claim at the Labor Tribunal, saying she had already brought evidence to the city's Labor Department. In a claim form shown to reporters, she stated she was fired unreasonably and illegally and it was due to her participation in a trade union.

“If the Wall Street Journal regrets this decision and agree that this wasn't right, there are ways to make repairs, perhaps still,” she said.

Cheng said she would meet with the department's investigators on Wednesday “to pursue this as a criminal matter.” She requested them to investigate her ex-employer for what she called “likely” violation of the employment ordinance.

Dow Jones, which publishes the newspaper, did not immediately comment.

Hong Kong journalists work in a narrowing space after drastic political changes in the city that was once seen as a bastion of media freedom in Asia.

After Beijing imposed a national security law in 2020, two local news outlets known for critical coverage of the government, Apple Daily and Stand News, were forced to shut down following the arrest of their senior management, including Apple Daily publisher Jimmy Lai. Lai is expected to testify in his defense next week in his landmark national security trial.

Two former editors at Stand News were convicted in August, the first journalists found guilty of sedition since the former British colony returned to China in 1997. One of them received a jail term of 21 months.

In March, Hong Kong enacted another security law, sparking worries among many journalists over a further decline in media freedom.

The termination of Cheng's contract in July sent shockwaves among Hong Kong's media workers. Cheng on Tuesday said her former employer insisted her job loss was a result of redundancy.

“Us being reporters, we hate being lied to by whoever it is, and least of all by our own supervisors and companies,” she said.

The Independent Association of Publishers’ Employees, a union run by and for the employees of Dow Jones, previously said in a statement that if Cheng was fired as what she claimed, the behavior was “unconscionable." It called on the publication to restore her job and provide full explanation about their decision to dismiss her.

Hong Kong ranked 135th out of 180 countries and territories in Reporters Without Borders’ latest World Press Freedom Index, down from 80 in 2021.

Selina Cheng, a former reporter at the Wall Street Journal, and chairperson of the Hong Kong Journalists Association shows reporters her claim form against her former employer for what she called unreasonable dismissal in Hong Kong on Tuesday, Nov.12, 2024. (AP Photo/ Kanis Leung)

Selina Cheng, a former reporter at the Wall Street Journal, and chairperson of the Hong Kong Journalists Association speaks to media in Hong Kong on Tuesday, Nov.12, 2024. Cheng said she'll sue the publication for sacking her because she joined a trade union. (AP Photo/ Kanis Leung)

WASHINGTON (AP) — Those ever-present TV drug ads showing patients hiking, biking or enjoying a day at the beach could soon have a different look: New rules require drugmakers to be clearer and more direct when explaining their medications' risks and side effects.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration spent more than 15 years crafting the guidelines, which are designed to do away with industry practices that downplay or distract viewers from risk information.

Many companies have already adopted the rules, which become binding Nov. 20. But while regulators were drafting them, a new trend emerged: thousands of pharma influencers pushing drugs online with little oversight. A new bill in Congress would compel the FDA to more aggressively police such promotions on social media platforms.

“Some people become very attached to social media influencers and ascribe to them credibility that, in some cases, they don’t deserve,” said Tony Cox, professor emeritus of marketing at Indiana University.

Still, TV remains the industry's primary advertising format, with over $4 billion spent in the past year, led by blockbuster drugs like weight-loss treatment Wegovy, according to ispot.tv, which tracks ads.

The new rules, which cover both TV and radio, instruct drugmakers to use simple, consumer-friendly language when describing their drugs, without medical jargon, distracting visuals or audio effects. A 2007 law directed the FDA to ensure that drug risk information appears “in a clear, conspicuous and neutral manner.”

FDA has always required that ads give a balanced picture of both benefits and risks, a requirement that gave rise to those long, rapid-fire lists of side effects parodied on shows like “ Saturday Night Live.”

But in the early 2000s, researchers began showing how companies could manipulate images and audio to de-emphasize safety information. In one example, a Duke University professor found that ads for the allergy drug Nasonex, which featured a buzzing bee voiced by Antonio Banderas, distracted viewers from listening to side effect information, making it harder to remember.

Such overt tactics have largely disappeared from drug ads.

“In general, I would say the ads have gotten more complete and transparent,” says Ruth Day, director of the medical cognition lab at Duke University and author of the Nasonex study.

The new rules are “significant steps forward,” Day said, but certain requirements could also open the door to new ways of downplaying risks.

One requirement instructs companies to show on-screen text about side effects while the audio information plays. A 2011 FDA study found that combining text with audio increased recall and understanding.

But the agency leaves it to companies to decide whether to display a few keywords or a full transcript.

“You often cannot put all that on the screen and expect people to read and understand it,” Day said. “If you wanted to hide or decrease the likelihood of people remembering risk information, that could be the way to do it.”

Viewers tend to tune out long lists of warnings and other information. But experts who work with drug companies don’t expect those lists to disappear. While the guidelines describe how the information should be presented, companies still decide the content.

“If you’re a company and you’re worried about possible FDA enforcement or product liability and other litigation, all your incentives are to say more, not less,” said Torrey Cope, a food and drug lawyer who advises companies.

Experts also say the new rules will have little effect on the overall tone and appearance of ads.

“The most salient element of these ads are the visuals, and they are uniformly positive,” said Cox. “Even if the risk message is about, for instance, sudden heart failure, they’re still showing someone diving into a swimming pool.”

The new rules come as Donald Trump's advisers begin floating plans for the FDA and the pharmaceutical industry.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr., an anti-vaccine activist who has advised the president-elect, wants to eliminate TV drug ads. He and other industry critics point out that the U.S. and New Zealand are the only countries where prescription drugs can be promoted on TV.

Even so, many companies are looking beyond TV and expanding into social media. They often partner with patient influencers who post about managing their conditions, new treatments or navigating the health system.

“They’re teaching people to live a good life with their disease, but then some of them are also paid to advertise and persuade,” said Erin Willis, who studies advertising and media at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Advertising executives say companies like the format because it’s cheaper than TV and consumers generally feel influencers are more trustworthy than companies.

FDA’s requirement for truthful, balanced risk and benefit information applies to drugmakers, leaving a loophole for both influencers and telehealth companies like Hims, Ro and Teledoc, who may not have a direct financial connection to makers of the drugs they’re promoting.

The issue has attracted attention from members of Congress.

“The power of social media and the deluge of misleading promotions has meant too many young people are receiving medical advice from influencers instead of their health care professional,” Sens. Dick Durbin of Illinois and Mike Braun of Indiana wrote the FDA in a February letter.

A recently introduced bill from the senators would bring influencers and telehealth companies clearly under FDA’s jurisdiction, requiring them to disclose risk and side effect information. The bill also would require drugmakers to publicly disclose payments to influencers.

“It’s asking the FDA to take a more serious stance with this kind of marketing,” said Willis. "They know it’s happening, but they could be doing more and their regulations haven’t been updated since 2014."

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

This combination of images from video shows scenes from Nasonex television commercials broadcast in the U.S. in the 2000s. (AP Photo)