LONDON (AP) — Facebook and Instagram users in Europe will get the option to see less personalized ads if they don't want to pay for an ad-free subscription, social media company Meta said Tuesday, bowing to pressure from Brussels over privacy and digital competition concerns.

Meta Platforms has been offering European Union an ad-free subscription option for about a year to comply with the continent's strict data privacy rules, but regulators had accused the company of giving people a false choice.

The company said in a blog post that while people will still be able to choose between the subscription and existing free versions, it would also start giving free users an extra option over the coming weeks to see digital ads that are less personalized.

This means ads will be targeted at users based only on what they see during their current session on Facebook or Instagram going back no more than two hours, plus minimal personal information such as age, location, gender as well as how they engage with ads.

Data from all of a user's previous time spent on Facebook or Instagram, which is typically combined to precisely target an individual with tailored ads, won't be used.

“While this new choice is designed to give people an additional control over their data and ad experience, it may result in ads that are less relevant to a person’s interests,” Meta said in a blog post. “That means people will see ads that they don’t find as interesting. This drop in relevance is inevitable given that drastically reduced data is being used to show these less personalized ads to people.”

People who choose the new option will see ad breaks that can't be skipped for a few seconds, Meta said.

European Union regulators had accused Meta of breaching the 27-nation bloc's digital rules when it gave user the option to pay a monthly fee to avoid being targeted by ads based on their personal data.

The U.S. tech giant had rolled out the option after the European Union’s top court ruled Meta must first get consent before showing ads to users, in a decision that threatened its business model of tailoring ads based on individual users’ online interests and digital activity.

The company also said Tuesday it's slashing monthly subscription prices for the ad-free option. Web users will pay 5.99 euros ($6.36), down from 9.99 euros previously, while iPhone and Android users will be charged 7.99 euros instead of 12.99 euros, which includes commissions charged by the Apple and Google mobile app stores.

Meta's new subscription model could hit the company's lucrative digital ad business in one of its biggest markets. The company said it has already factored the new offering into its most recent business outlook and financial guidance.

The options are available to users 18 and older in the EU’s 27 member countries, plus Switzerland, Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein.

FILE - The Meta logo is seen at the Vivatech show in Paris, France, on June 14, 2023. (AP Photo/Thibault Camus, File)

The first five games of the Winnipeg-St. Louis series have all had the same result. The home team won.

The Blues need that trend to continue Friday — or else.

Game 6 of the Jets-Blues matchup awaits in St. Louis, with Winnipeg — the NHL's best team in the regular season — holding a 3-2 series lead. The Blues rolled to wins on their home ice in Games 3 and 4, taking those games by scores of 7-2 and 5-1 to extend a run of invincibility there that has lasted for more than two months.

“It's a tough building to play in,” Jets forward Vladislav Namestnikov said. “But I know we can get the win there.”

If they do, they will be doing so without star Mark Scheifele, the team's second-leading scorer and leader in game-winning goals this season. Scheifele was hurt in Game 5 and wasn't flying with Winnipeg to St. Louis on Thursday for Game 6.

The teams had different opinions about when Scheifele got hurt, but the bottom line is the Jets will be missing a big part of their team for a potential closeout game.

“Certainly, not having him is going to be huge,” Jets coach Scott Arniel said Thursday. “But at the end of the day, last night, our three centermen had to step up and play big minutes and did a great job. ... So proud of the group, how everybody stepped up. It's kind of what our team has done all year. Guys go down, other guys step in.”

Winnipeg was the most recent visiting team to win in St. Louis — but that was more than two months ago.

The Blues have put together the longest home winning streak in the NHL this season, a 14-game run that started on Feb. 23 and hasn't stopped. St. Louis has outscored opponents 69-25 in that span at home, winning by an average of a whopping 3.14 goals per game.

“We've played some good hockey at home for a couple months now,” St. Louis' Brayden Schenn said. “We're comfortable there.”

That's a bit of an understatement. The Blues have simply looked like a different team in their own building; St. Louis has had stretches of three goals in five minutes, three goals in eight minutes and three goals in 15 minutes so far in this series on its own ice.

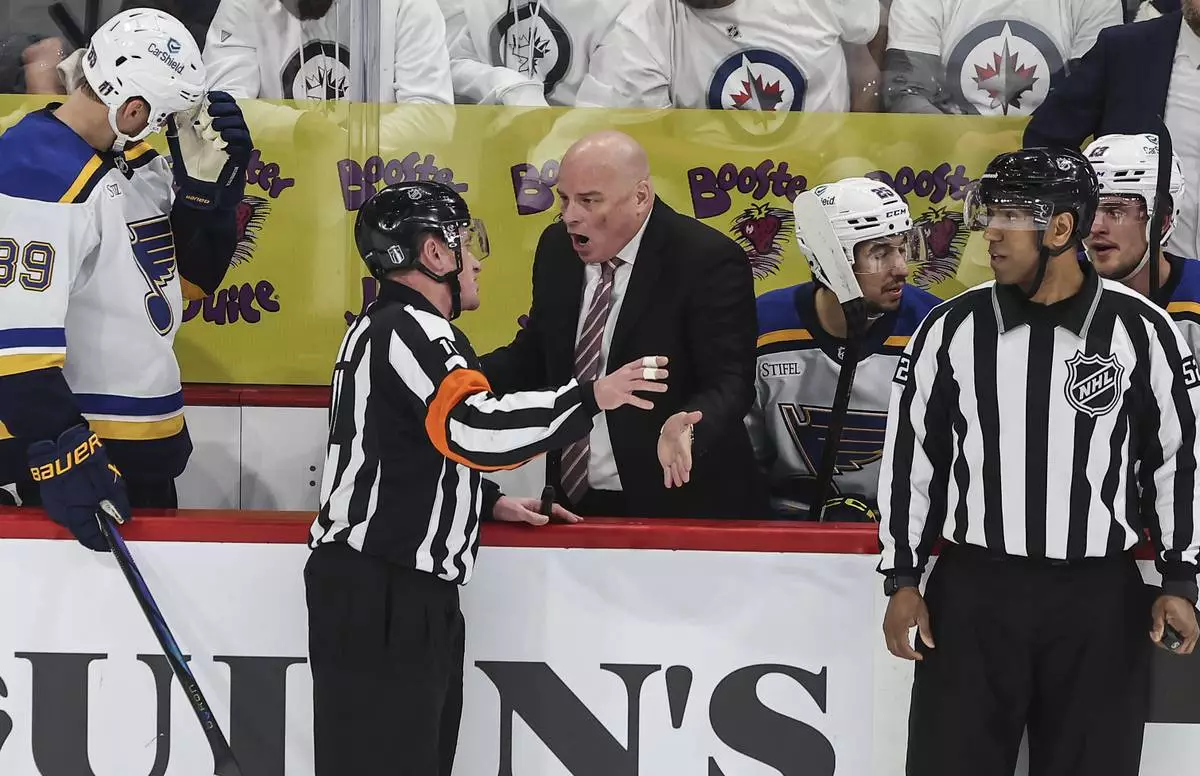

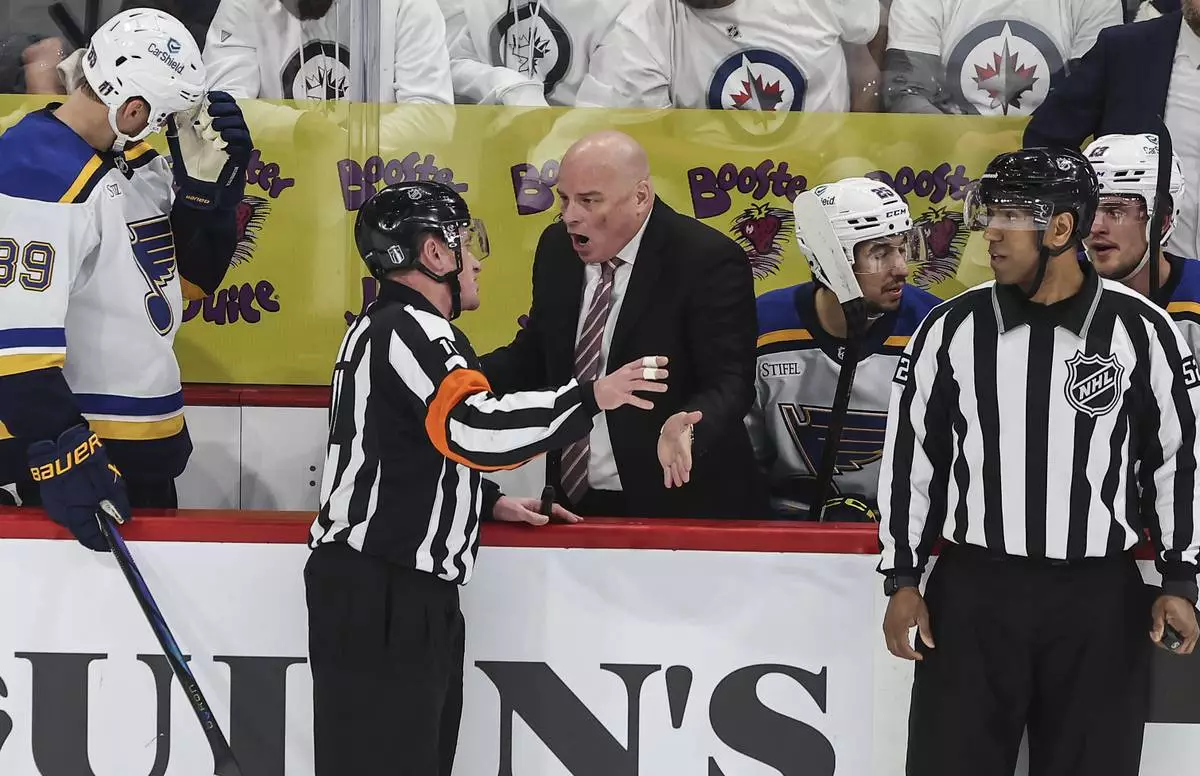

They looked nothing like that club in Game 5, a 5-3 Winnipeg win that probably wasn't as close as that score would make it seem. Blues coach Jim Montgomery didn't waste any time thinking about that game once the final horn sounded.

“We can analyze every part of it. They were better,” Montgomery said. “So, we're on to the next one.”

It took St. Louis a long — long — time to get home on Thursday, after their travel plans were seriously delayed.

The Blues had plane issues trying to leave Winnipeg and, after a replacement jet was sent to Manitoba, they finally took off about eight hours behind schedule.

The Jets landed in St. Louis around 3 p.m. Central time on Thursday, actually a tiny bit ahead of schedule, while the Blues didn't get there until about 9 p.m.

When/Where to Watch: Game 6, Friday. 8 p.m. (TNT/truTV/Max)

Series: Jets lead 3-2

Winnipeg hasn't closed out a series with a road win since 2018, and getting it done Friday will be difficult.

Forget St. Louis' 14-game home winning streak, which is impressive enough. The Blues simply don't give up scoring chances in their building; they have allowed two goals or less in 11 of those 14 wins, and that level of stinginess puts enormous pressure on the other team's netminder.

That said, Winnipeg goalie and MVP hopeful Connor Hellebuyck has reveled in big moments like this all season.

The newly announced Hart Trophy finalist — alongside Edmonton forward Leon Draisaitl and Tampa Bay forward Nikita Kucherov — led the NHL with 47 wins, a 2.00 GAA, and a .925 save percentage this season, had eight shutouts, steered Winnipeg to its first Presidents’ Trophy, won the William M. Jennings Trophy (fewest goals allowed) for the second straight year and seems like a lock for the Vezina Trophy (top goalie) for the second straight year and third time in six seasons.

If Hellebuyck does win the Hart as MVP, he'd be the fourth goalie in the league's expansion era to do it alongside Dominik Hasek, José Théodore and Carey Price. He was pulled twice in St. Louis and has a gaudy 3.96 goals-against average and .822 save percentage in this series — including all three wins.

“He's our best player,” Namestnikov said.

AP NHL: https://apnews.com/hub/nhl

St. Louis Blues' Brayden Schenn (10) celebrates with Colton Parayko (55) after scoring against the Winnipeg Jets during the second period in Game 4 of an NHL hockey first-round playoff series Sunday, April 27, 2025, in St. Louis. (AP Photo/Connor Hamilton)

St. Louis Blues goaltender Jordan Binnington (50) saves the shot from Winnipeg Jets' Jaret Anderson-Dolan (28) during first period NHL playoff action in Winnipeg on Wednesday, April 30, 2025. (John Woods/The Canadian Press via AP)

Winnipeg Jets' Dylan DeMelo (2), Vladislav Namestnikov (7), Gabriel Vilardi (13) and Kyle Connor (81) celebrate DeMelo's goal against the St. Louis Blues during second period NHL playoff action in Winnipeg on Wednesday, April 30, 2025. (John Woods/The Canadian Press via AP)

St. Louis Blues head coach Jim Montgomery questions referee Kelly Sutherland during first period NHL playoff action against the Winnipeg Jets in Winnipeg on Wednesday, April 30, 2025. (John Woods/The Canadian Press via AP)

St. Louis Blues goaltender Jordan Binnington (50) makes the save off Winnipeg Jets' Gabriel Vilardi's (13) wraparound attempt during the third period of an NHL playoff game in Winnipeg on Wednesday, April 30, 2025. (John Woods/The Canadian Press via AP)

Winnipeg Jets and St. Louis Blues players rough it up after the Blues score during the third period of an NHL playoff game in Winnipeg on Wednesday, April 30, 2025. (John Woods/The Canadian Press via AP)