BAKU, Azerbaijan (AP) — For the third straight year, efforts to fight climate change haven't lowered projections for how hot the world is likely to get — even as countries gather for another round of talks to curb warming, according to an analysis Thursday.

At the United Nations climate talks, hosted in Baku, Azerbaijan, nations are trying to set new targets to cut emissions of heat-trapping gases and figure out how much rich nations will pay to help the world with that task.

But Earth remains on a path to be 2.7 degrees Celsius (4.9 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than pre-industrial times, according to Climate Action Tracker, a group of scientists and analysts who study government policies and translate that into projections of warming.

If emissions are still rising and temperature projections are no longer dropping, people should wonder if the United Nations climate negotiations — known as COP — are doing any good, said Climate Analytics CEO Bill Hare.

“There’s an awful lot going on that’s positive here, but on the big picture of actually getting stuff done to reduce emissions ... to me it feels broken,” Hare said.

The world has already warmed 1.3 degrees Celsius (2.3 Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial times. That's near the 1.5-degree (2.7 F) limit that countries agreed to at 2015 climate talks in Paris. Climate scientists say the atmospheric warming, mainly from human burning of fossil fuels, is causing ever more extreme and damaging weather including droughts, flooding and dangerous heat.

Climate Action Tracker does projections under several different scenarios, and in some cases, those are going up slightly.

“This is driven highly by China,” said Sofia Gonzales-Zuniga of Climate Analytics. Even though China's fast-rising emissions are starting to plateau, they are peaking higher than anticipated, she said.

Another upcoming factor not yet in the calculations is the U.S. elections. A Trump administration that rolls back the climate policies in the Inflation Reduction Act, and carries out the conservative blueprint Project 2025, would add 0.04 degree Celsius (0.07 Fahrenheit) to warming projections, Gonzales-Zuniga said. That's not much, but it could be more if other nations use it as an excuse to do less, she said.

“Fossil fuels and emissions are not peaking,” said Sherry Rehman, chair of climate and environment committee in Pakistan’s senate. After 29 years of climate talks, Rehman said countries are “still talking in bumper stickers.”

“We need a transformative solution. We need strong delivery,” Rehman said.

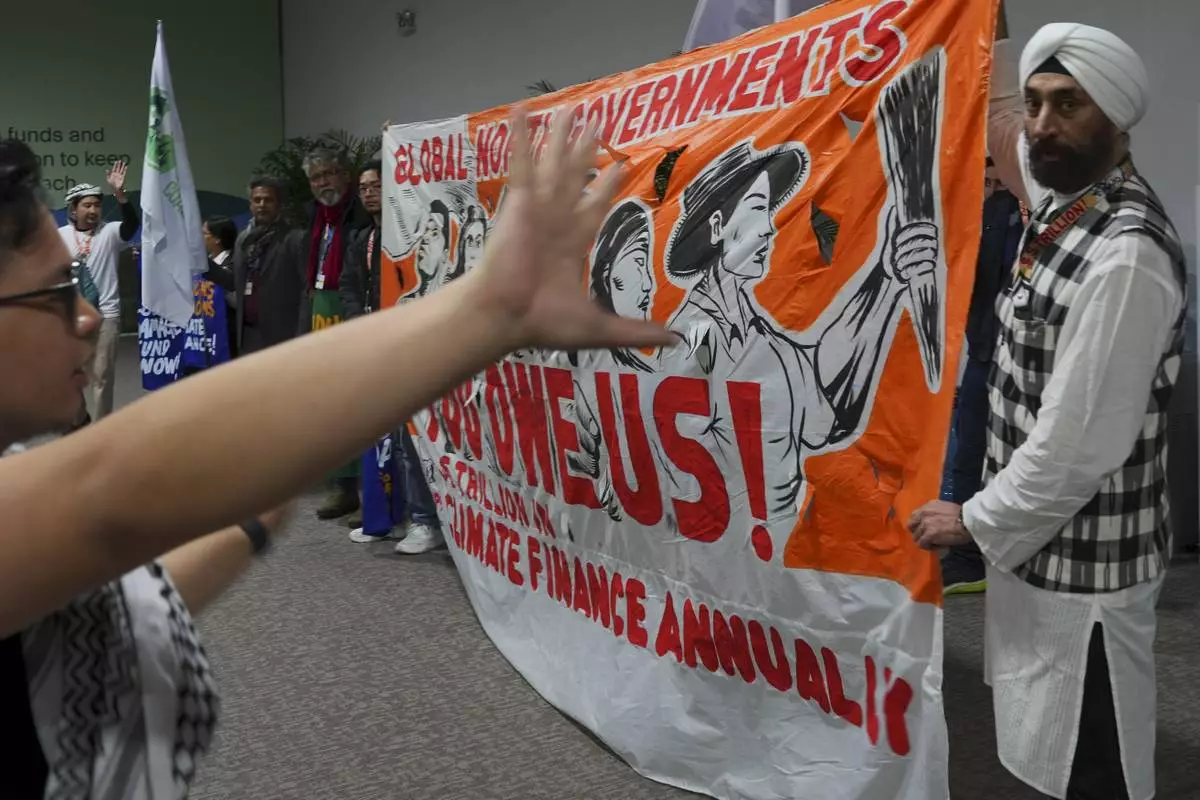

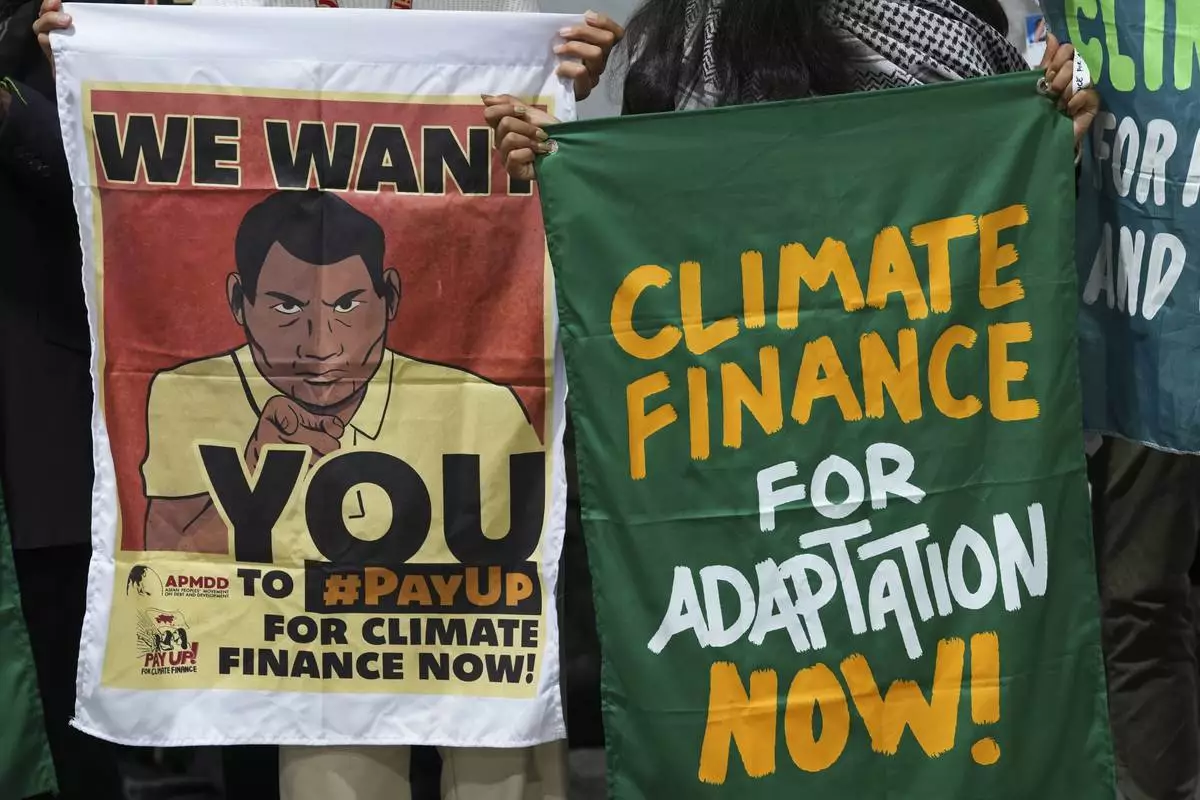

The major battle in Baku is over how much rich nations will pay for developing countries to decarbonize their energy systems, cope with future harms of climate change and pay for damage from warming's extreme weather.

A special independent group of experts commissioned by United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres issued its own estimate of costs and finances on Thursday, calling for a tripling of the old commitment. It said about $1 trillion a year is needed by developing nations from all outside sources, not just government grants.

“Advanced economies need to demonstrate a credible commitment” to helping poor nations, the report said.

Negotiations on a grand total and structuring the overall amount have taken “a step back” when a draft of just a few pages that was worked on for a year was rejected and the latest proposal with many options has more than 30 pages, said top European negotiator Veronika Bagi of Hungary. European Commission negotiator Jacob Werksman said there’s a “very significant gap″ between what rich and poor nations propose.

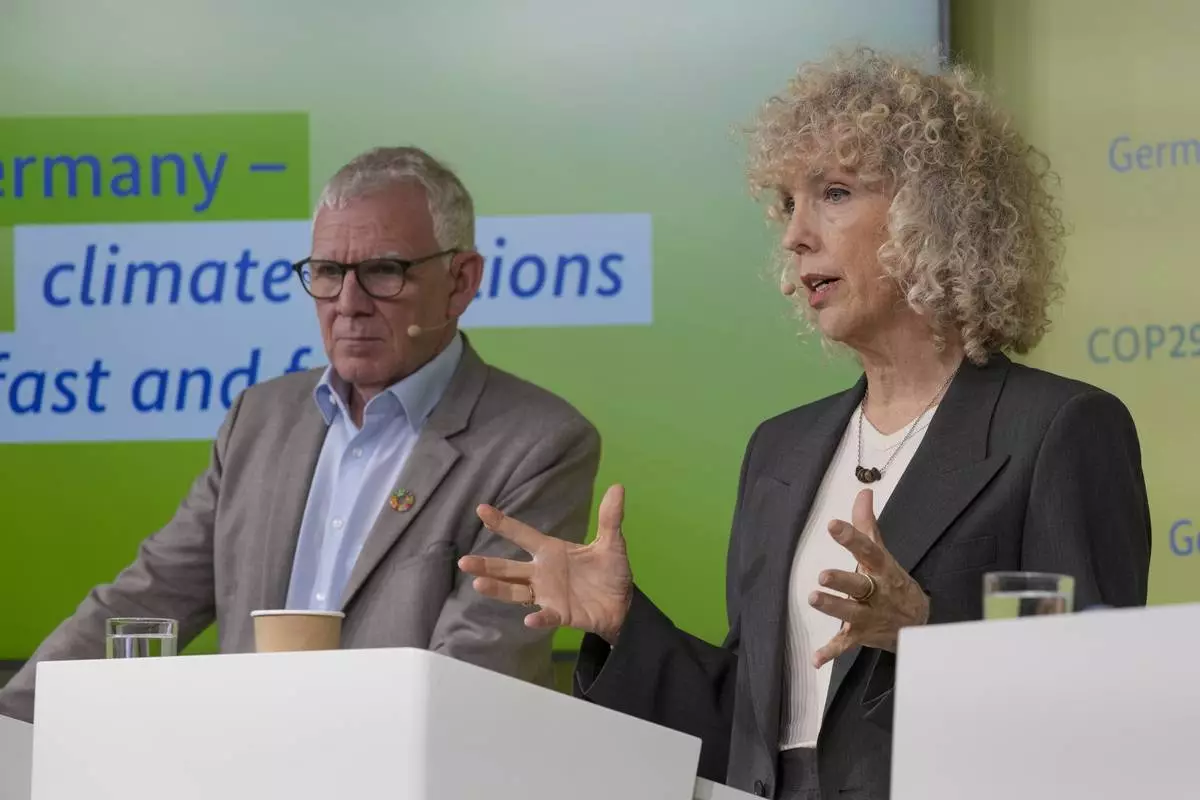

German climate envoy Jennifer Morgan said “private investment has to be brought to the table” in order to fulfill developing countries needs. But Mariana Paoli of Christian Aid said any number that comes out of negotiations that's not based in publicly-financed grants “will be meaningless.”

Relying on the private sector means climate cash will not be “needs based, it will be profit-driven," she said, adding that crises like the COVID-19 pandemic and bank bailouts proves that public funds are available.

“It’s about fairness, it’s about justice,” she said.

Getting climate cash is personal for many activists from vulnerable nations, like Sandra Leticia Guzman Luna, who is from Mexico and the director of the climate finance group for Latin America and the Caribbean. “We are observing the climate impacts causing a lot of costs, not only economic costs but also human losses,” she said.

Argentina withdrew from the climate talks on Wednesday on the orders of its president, climate skeptic Javier Milei. The Argentine government did not respond to requests from The Associated Press for comment.

Climate activists called the decision regrettable.

“It’s difficult to understand how a climate-vulnerable country like Argentina would cut itself from critical support," said Anabella Rosemberg, an Argentina native who works as a senior adviser at Climate Action Network International.

Also Wednesday, France's environment minister, who was set to lead the delegation, pulled out of the talks after Azerbaijan president Ilham Aliyev called out France and the Netherlands for their colonial histories.

Agnès Pannier-Runacher called Aliyev’s remarks on France and Europe “unacceptable." Speaking at the French Senate on Wednesday, Pannier-Runacher criticized Azerbaijan’s leader for using the fight against climate change “for a shameful personal agenda.”

“The direct attacks on our country, its institutions and its territories are unjustifiable,” she said.

COP29 negotiator Rafiyev declined to comment Thursday on Pannier-Runacher's decision, but said “Azerbaijan has made sure we have inclusive process.”

“We have opened our door for everyone to come for constructive, critical discussions,” he said.

Associated Press reporter Sylvie Corbet contributed from Paris.

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Activist Luisa Neubauer, of Germany, records on her phone at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Mukhtar Babayev, COP29 President, walks through the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

A person walks past art in the Turkey Pavilion at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

People walk outside the Baku Olympic Stadium at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Rafiq Maqbool)

Principal advisor for climate at the European Commission Jacob Werksman attends a news conference at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Rafiq Maqbool)

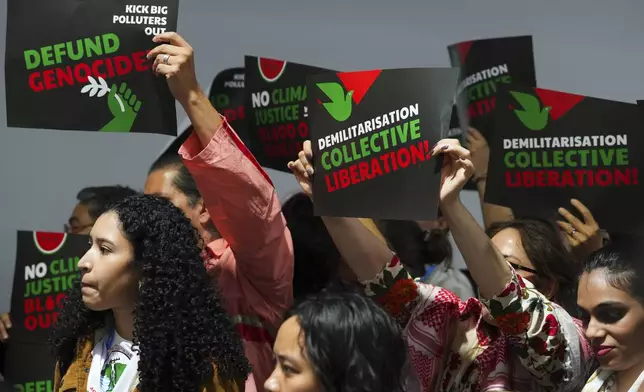

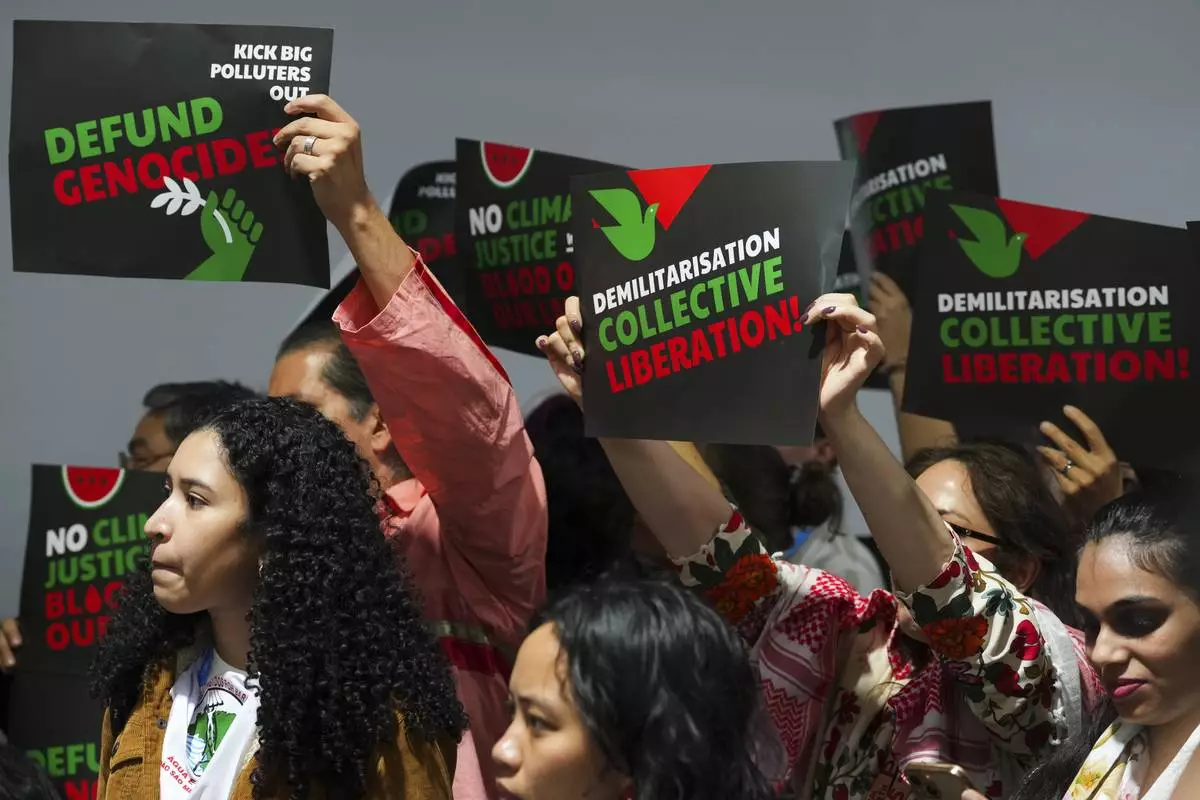

Activists participate in a demonstration at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

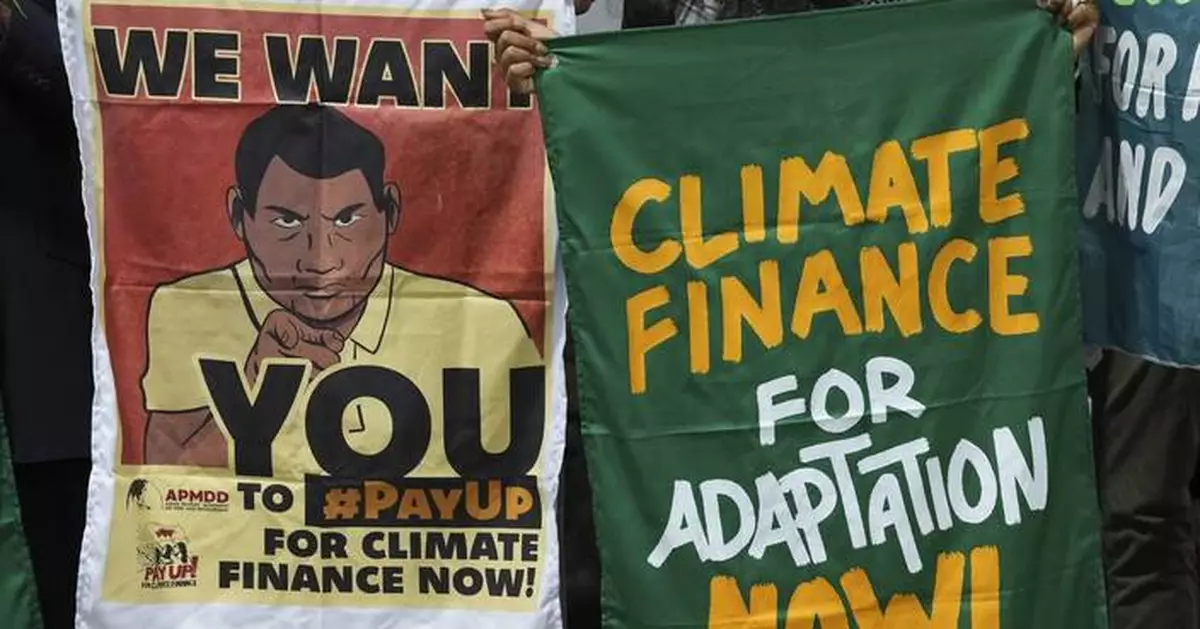

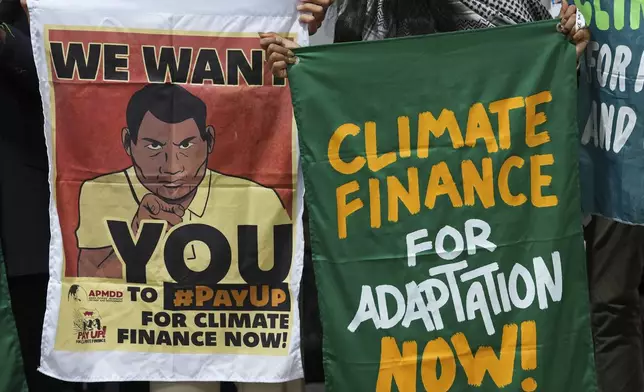

Activists participate in a demonstration calling for climate finance during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

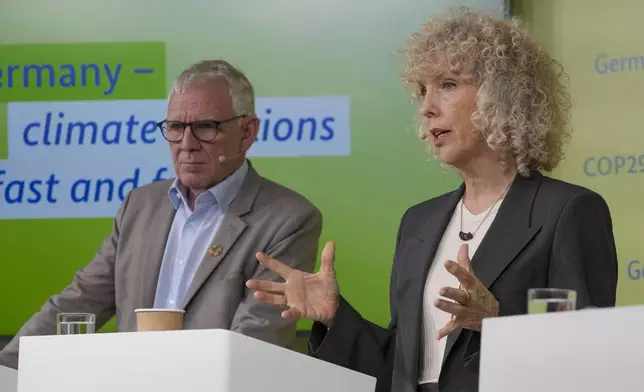

State secretary in Germany's economic cooperation ministry Jochen Flasbarth, left, and Jennifer Morgan, Germany climate envoy, attend a news conference at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

Activists participate in a demonstration for climate justice during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Attendees arrive for the day at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Activists participate in a demonstration calling for climate finance during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

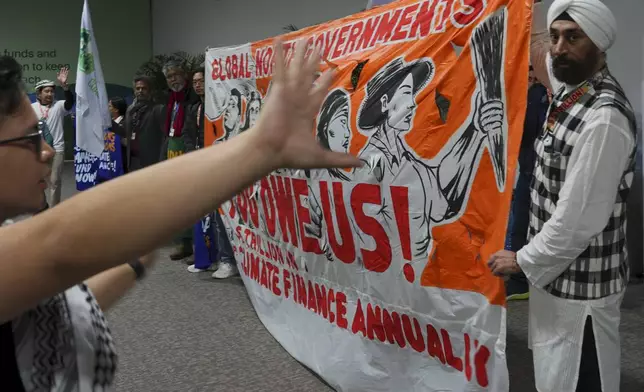

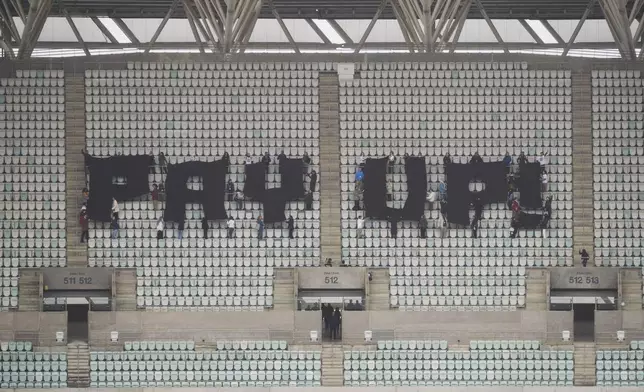

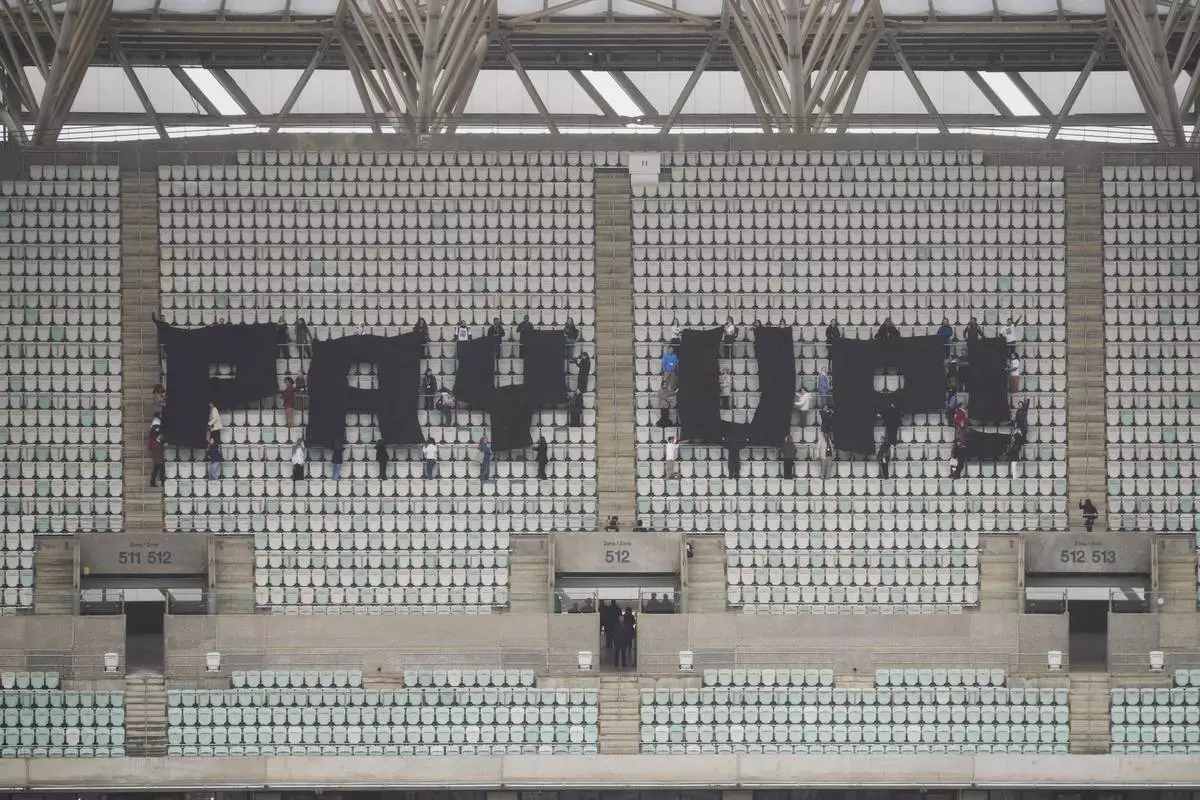

Activists with signs spell out "pay up" for climate finance in the Baku Olympic Stadium during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

Attendees arrive for the day at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Rafiq Maqbool)

Activists participate in a demonstration for climate finance at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)