KYIV, Ukraine (AP) — A high-tech factory in central Russia has created a new, deadly force to attack Ukraine: a small number of highly destructive thermobaric drones surrounded by huge swarms of cheap foam decoys.

The plan, which Russia dubbed Operation False Target, is intended to force Ukraine to expend scarce resources to save lives and preserve critical infrastructure, including by using expensive air defense munitions, according to a person familiar with Russia’s production and a Ukrainian electronics expert who hunts them from his specially outfitted van.

Neither radar, sharpshooters nor even electronics experts can tell which drones are deadly in the skies.

Here's what to know from AP's investigation:

Unarmed decoys now make up more than half the drones targeting Ukraine and as much as 75% of the new drones coming out of the factory in Russia’s Alabuga Special Economic Zone, according to the person familiar with Russia’s production, who spoke on condition of anonymity because the industry is highly sensitive, and the Ukrainian electronics expert.

The same factory produces a particularly deadly variant of the Shahed unmanned aircraft armed with thermobaric warheads, the person said.

During the first weekend of November, the Kyiv region spent 20 hours under air alert, and the sound of buzzing drones mingled with the boom of air defenses and rifle shots. In October, Moscow attacked with at least 1,889 drones – 80% more than in August, according to an AP analysis tracking the drones for months.

On Saturday, Russia launched 145 drones across Ukraine, just days after the re-election of Donald Trump threw into doubt U.S. support for the country.

Since summer, most drones crash, are shot down or are diverted by electronic jamming, according to an AP analysis of the Ukrainian military briefings. Less than 6% hit a discernible target, according to the data analyzed by AP since the end of July. But the sheer numbers mean a handful can slip through every day – and that is enough to be deadly.

Tatarstan’s Alabuga zone, an industrial complex about 1,000 kilometers (600 miles) east of Moscow, is a laboratory for Russian drone production. Originally set up in 2006 to attract businesses and investment to Tatarstan, it expanded after the 2022 invasion of Ukraine and some sectors switched to military production, adding new buildings and renovating existing sites, according to satellite images analyzed by The Associated Press.

In social media videos, the factory promoted itself as an innovation hub. But David Albright of the Washington-based Institute for Science and International Security said Alabuga’s current purpose is purely to produce and sell drones to Russia‘s Ministry of Defense. The videos and other promotional media were taken down after an AP investigation found that many of the African women recruited to fill labor shortages there complained they were duped into taking jobs at the plant.

Russia and Iran signed a $1.7 billion deal for the Shaheds in 2022, after President Vladimir Putin invaded neighboring Ukraine, and Moscow began using Iranian imports of the unmanned aerial vehicles, or UAVs, in battle later that year. Soon after the deal was signed, production started in Alabuga.

The most fearsome Shahed adaptation so far designed at the plant is armed with thermobarics, also known as vacuum bombs, the person with knowledge of Russian drone production said.

The plan to develop unarmed decoy drones at Alabuga was developed in late 2022, according to the person with knowledge of Russian drone production. Production of the decoys started earlier this year, said the person, who agreed to speak only on condition of anonymity. Now the plant turns out about 40 of the unarmed drones a day and around 10 armed ones, which are more expensive and take longer to produce.

From a military point of view, thermobarics are ideal for going after targets that are either inside fortified buildings or deep underground. They create a vortex of high pressure and heat that penetrates the thickest walls and, at the same time, sucks out all the oxygen in their path.

Alabuga’s thermobaric drones are particularly destructive when they strike buildings, because they are also loaded with ball bearings to cause maximum damage even beyond the superheated blast.

Serhii Beskrestnov, a Ukrainian electronics expert and more widely known as Flash whose black military van is kitted out with electronic jammers to down drones, said the thermobarics were first used over the summer and estimated they now make up between 3% and 5% of all drones.

They have a fearsome reputation because of the physical effects even on people caught outside the initial blast site: Collapsed lungs, crushed eyeballs, brain damage, according to Arthur van Coller, an expert in international humanitarian law at South Africa’s University of Fort Hare.

For Russia, the benefits are huge.

An unarmed drone costs considerably less than the estimated $50,000 for an armed Shahed drone and a tiny fraction of the cost of even a relatively inexpensive air defense missile. One decoy with a live-feed camera allows the aircraft to geolocate Ukraine’s air defenses and relay the information to Russia in the final moments of its mechanical life. And the swarms have become a demoralizing fact of life for Ukrainians.

Burrows reported from Washington D.C.

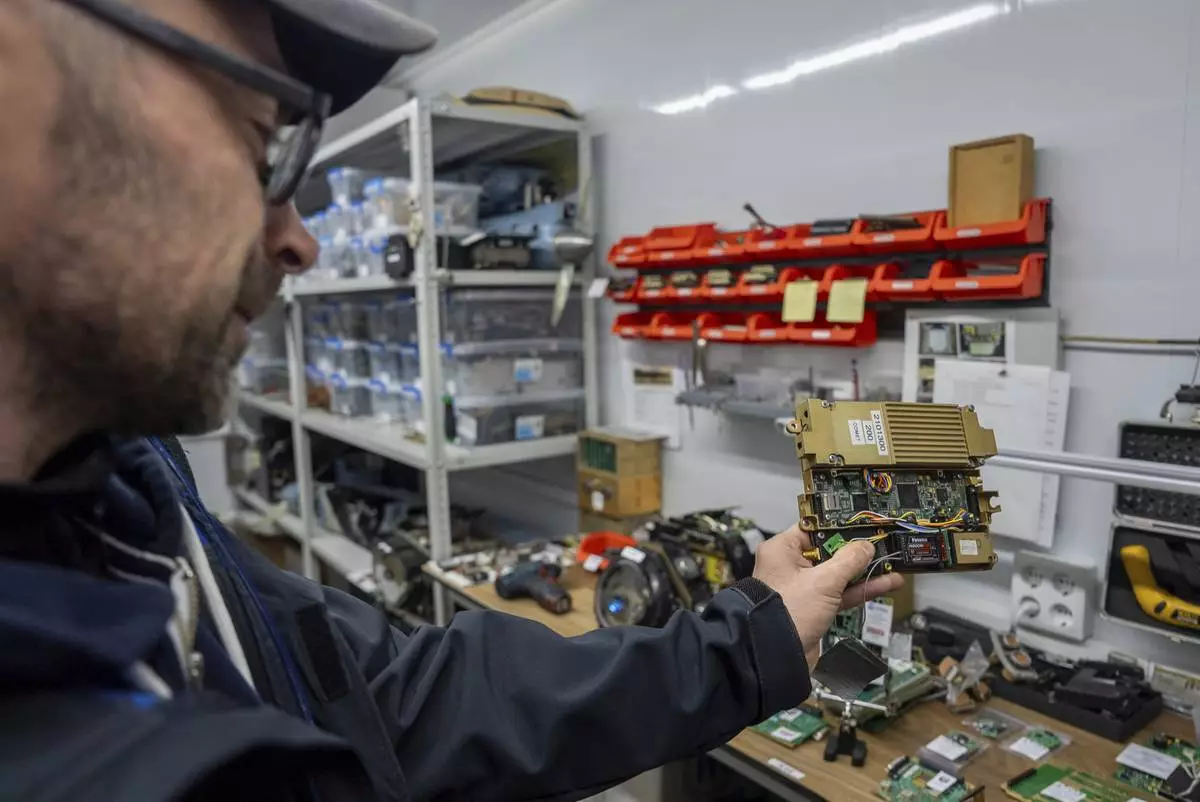

Andrii Kulchytskyi the head of the military research laboratory at the Kyiv Scientific Research Institute of Forensic Expertise sits in his workspace in Kyiv, Ukraine, Tuesday, Oct. 15, 2024. (AP Photo/Alex Babenko)

Ukrainian soldiers of the 3rd assault brigade fly an FPV exploding drone over Russian positions in Kharkiv region, Ukraine, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

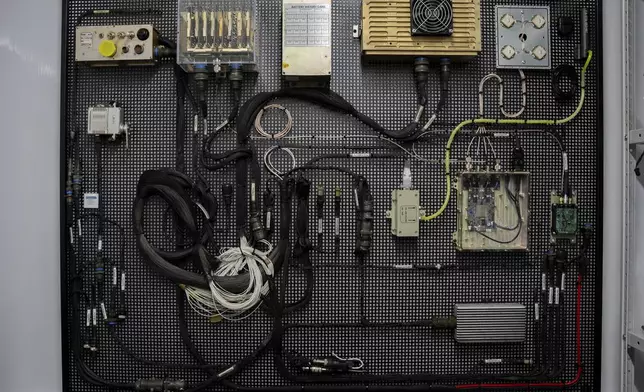

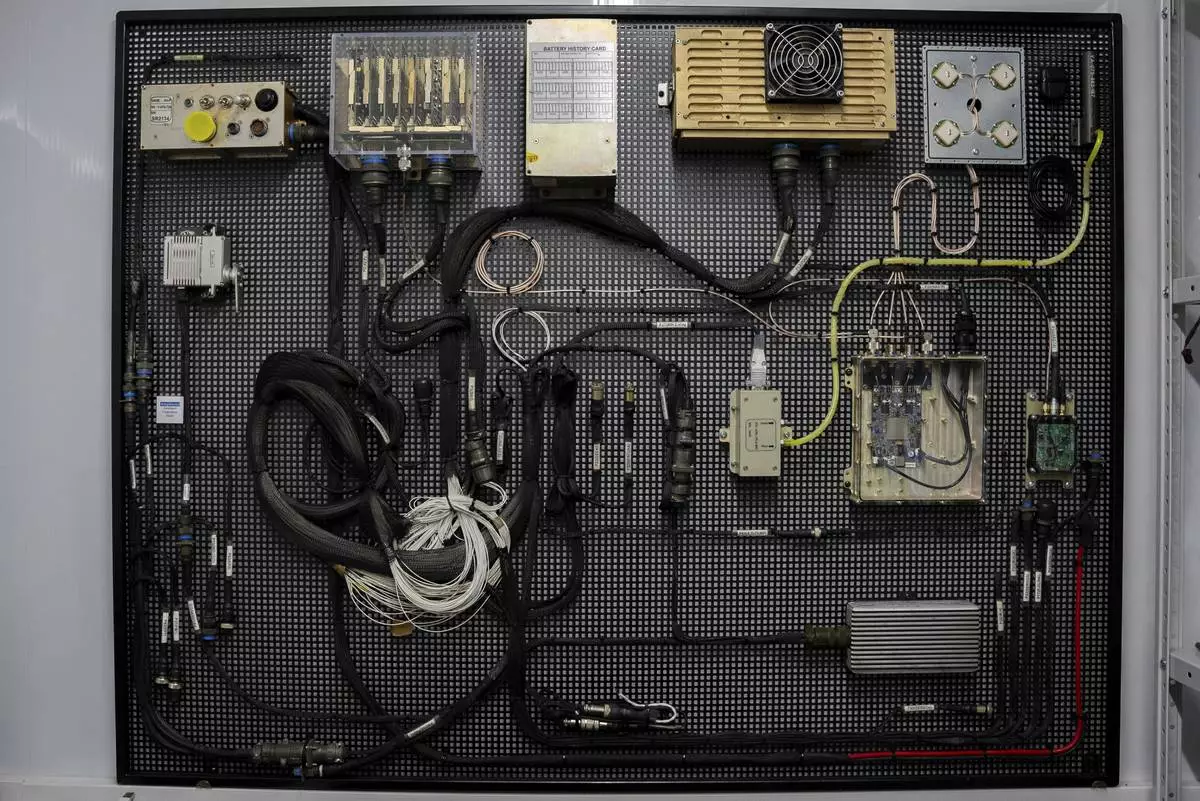

The internal mechanism of Shahed drone is seen in Kyiv Scientific Research Institute of Forensic Expertise in Kyiv, Ukraine, Tuesday, Oct. 15, 2024. (AP Photo/Alex Babenko)

A worker of the Kyiv Scientific Research Institute of Forensic Expertise shows parts of Russian weapons in Kyiv, Ukraine, Tuesday, Oct. 15, 2024. (AP Photo/Alex Babenko)

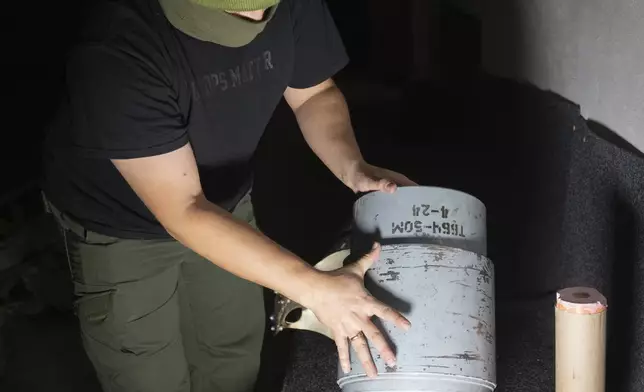

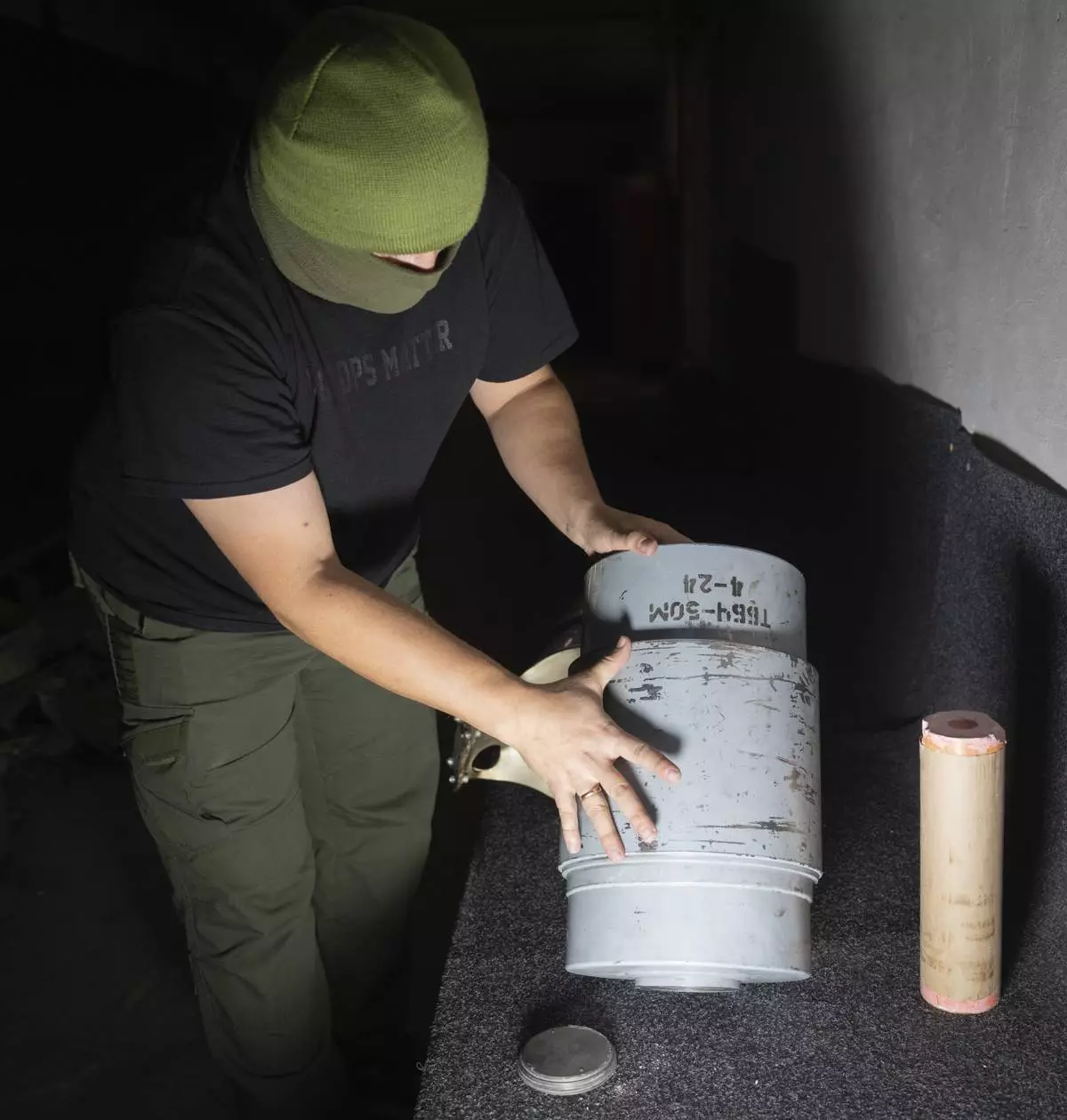

A Ukrainian officer examines a downed Shahed drone with thermobaric charge launched by Russia in a research laboratory in an undisclosed location in Ukraine Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024. (AP Photo/Efrem Lukatsky)

Flames and smoke rise from a residential building after the attack of Russian drones in Kyiv, Ukraine, Friday, Oct. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Alex Babenko)

A medical emergency team collects the body of a victim who died after the Russian attack in Kyiv, Ukraine, Friday, Oct. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Alex Babenko)

A Ukrainian officer, callsign Raccoon, shows a thermobaric charge of a downed Shahed drone launched by Russia in a research laboratory in an undisclosed location in Ukraine Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024. (AP Photo/Efrem Lukatsky)

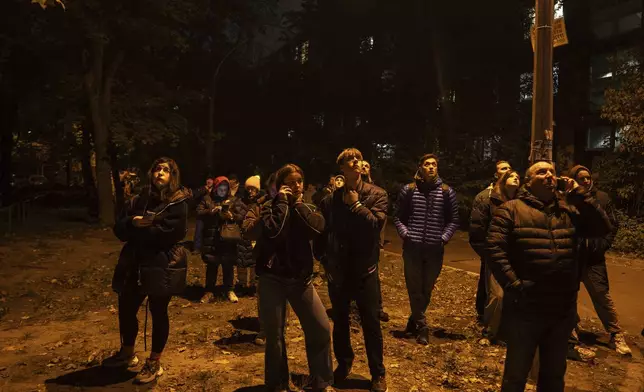

Local residents look up at the fire in a residential building after an attack of Russian drones in Kyiv, Ukraine, Friday, Oct. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Alex Babenko)

A couple comforts each other while looking at the fire in a residential building after the attack of Russian drones in Kyiv, Ukraine, Friday, Oct. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Alex Babenko)

A Ukrainian officer shows a thermobaric charge of a downed Shahed drone launched by Russia in a research laboratory in an undisclosed location in Ukraine Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024. (AP Photo/Efrem Lukatsky)

Serhii Beskrestnov, more widely known as Flash, a Ukrainian electronics expert, who hunts drones for the military, stands near his kitted-out black van in Kyiv, Ukraine, Monday, Nov. 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Hanna Arhirova)

Flames and smoke rise from a residential building after the attack of Russian drones in Kyiv, Ukraine, Friday, Oct. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Alex Babenko)