CHURCHILL, Manitoba (AP) — Sgt. Ian Van Nest rolls slowly through the streets of Churchill, his truck outfitted with a rifle and a barred back seat to hold anyone he has to arrest. His eyes dart back and forth, then settle on a crowd of people standing outside a van. He scans the area for safety and then quietly addresses the group's leader, unsure of the man's weapons.

“How are you today?” Van Nest asks. The leader responds with a wary, “We OK for you here?”

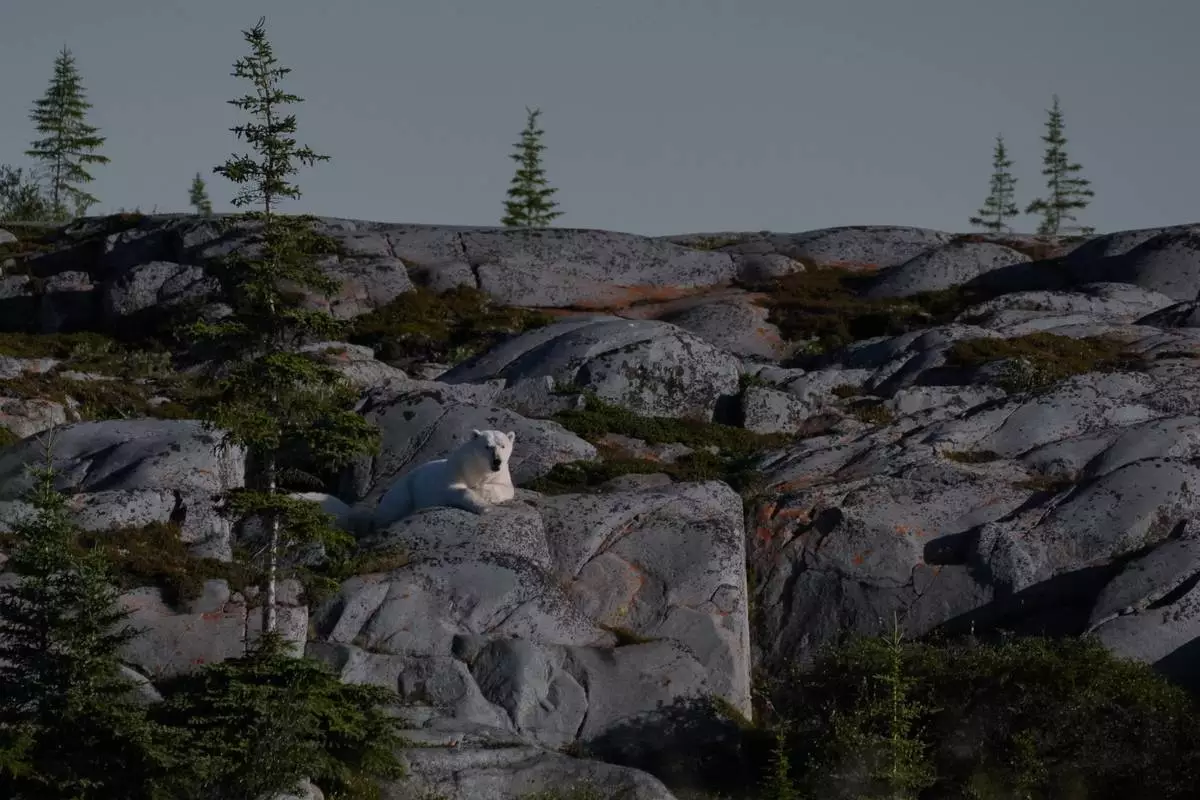

“You’re good. You got a lot of distance there. When you have people disembarking from the vehicle you should have a bear monitor,” Van Nest, a conservation officer for the province of Manitoba, cautions as the tourists gaze at a polar bear on the rocks. "So, if that’s you, just have your shotgun with you, right? Slugs and cracker shells if you have or a scare pistol.”

It's the beginning of polar bear season in Churchill, a tiny town on a spit of land jutting into Hudson Bay, and keeping tourists safe from hungry and sometimes fierce bears is an essential job for Van Nest and many others. And it's become harder as climate change shrinks the Arctic sea ice the bears depend on to hunt, forcing them to prowl inland earlier and more often in search of food, according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, a group of scientists that tracks how endangered species are.

“You're seeing more bears because there are more bears on the land for longer periods of time to be seen” and they are willing to take more risks, getting closer to people, said Polar Bears International research and policy director Geoff York. There are about 600 polar bears in this Western Hudson Bay population, about half what it was 40 years ago, but that's still close to one bear for every resident of Churchill.

Yet this remote town not only lives with the predator next door, but depends upon and even loves it. Visitors eager to see polar bears saved the town from shrinking out of existence when a military base closed in the 1970s, dropping the population from a few thousand to about 870. A 2011 government study calculated that the average polar bear tourist spends about $5,000 a visit, pumping more than $7 million into a tiny town that boasts fancy restaurants and more than two dozen small places to stay amid dirt roads and no stoplights.

“We’re obviously used to bears so (when you see one) you don’t start to tremble,” Mayor Mike Spence said. “It’s their area too. It’s important how the community coexists with bears and wildlife in general to really get along. We’re all connected.”

It's been more than a decade since a bear mauled two people in an alley late on Halloween night before a third person scared off the animal.

“It was the scariest thing that's ever happened in my life,” said Erin Greene, who along with a 72-year-old man who tried to fight off the bear with a shovel survived their injuries. Greene, who had come to Churchill the year before for a job in the tourist trade, said it was the other animals of Churchill — the beluga whales that she sings to as she runs paddleboat tours and her dozen rescued retired sled dogs — that helped her recover from the trauma.

There have been no attacks since then, but the town is watchful.

At Halloween, trick-or-treating occurs when bears are hungriest, and dozens of volunteers line the streets to keep trouble at bay. Any time of year, troublesome bears that wander into town too often may be put into the polar bear jail — a big Quonset hut-style structure with 28 concrete-and-steel cells — before being returned to the wild. The building doesn't fill up, but it can get busy enough to be noisy from banging and growling inside, Van Nest said.

Residents show polar bear pride in a way that mixes terror and fun, kind of like a rollercoaster.

“You know we're the polar bear capital of the world, right? We have the product, it's just about getting out there to see the bears safely,” said Dave Daley, who owns a gift shop, runs dog sleds and talks up the city like the former Chamber of Commerce president he is. “I always tell tourists or whatever ‘You know what, they’re the T. rex like, of the dinosaur era. They're the Lords of the Arctic. They'll eat you.”

Usually they don't.

The military base's rocket launch site seemed to keep bears away, and when it closed in the 1970s, they came around more, longtime residents said. So Churchill and province officials “put together a polar bear alert program to make sure the community members were looked after, protected,” said Spence, mayor since 1995.

The town's old curfew siren blares nightly at 10 p.m., suggesting to people that it's time to go home for safety from bears. But on this Saturday night, three different bonfire parties are going on at the town beach — a spot next to the school, library and hospital that is a particular hot spot for bears coming inland. Yet no one is leaving.

Then a truck shows up, and a lone figure — one of government's paid guards — gets out, armed with a shotgun. He walks out on the dunes about 100 yards from the parties and scans the horizon for polar bears. The guards are expected to scare any bears away with warning shots, flares, bear spray or noise — not kill them.

“It's just everybody watches out for everybody,” Spence said. “So it's just, it's just normal. It kicks into gear as a community that lives alongside polar bears, you're always accustomed to coming out of your house and you look like this and you look ahead. And that's just in your DNA now.”

Georgina Berg recalls growing up in the 1970s outside of Churchill, where many First Nations people lived, and how differently her father and mother reacted to a bear sighting. Her father, she said, would see a bear poking in garbage and just walk on by.

“He said, ‘If you don’t bother them, then they won’t bother you’," she recalled.

When a bear came near in later years, after her father had died, her mom was scared.

“Everything was like pandemonium. Everybody was yelling, and all the kids had to come in and everybody had to go home. And then we stayed silent in the house for a long time until we knew for sure that bear was gone, ” Berg recalled.

For Van Nest, the provincial officer, the group he came upon that day was plenty safe from a bear about 300 yards (meters) away. He said the bear was “putting on a bit of a show” for the tourists.

“This is a great situation to be in," he said. “The tourists are a safe distance away and the bear’s doing his natural thing and not being harassed by anybody.”

Read more of AP’s climate coverage at http://www.apnews.com/climate-and-environment

Follow Seth Borenstein on X at @borenbears

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

A person watches for polar bears near Hudson Bay, Saturday, Aug. 3, 2024, in Churchill, Manitoba. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

A polar bear statue stands near a road, Saturday, Aug. 3, 2024, in Churchill, Manitoba. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Erin Greene holds one of her rescued sled dogs, Thursday, Aug. 8, 2024, in Churchill, Manitoba. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

A polar bear trap sits outside the Polar Bear Holding Facility, Sunday, Aug. 4, 2024, in Churchill, Manitoba. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Tourists stand outside the Polar Bear Holding Facility, Sunday, Aug. 4, 2024, in Churchill, Manitoba. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

A polar bear stands near rocks, Tuesday, Aug. 6, 2024, in Churchill, Manitoba. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Waves from Hudson Bay crash onto shore, Wednesday, Aug. 7, 2024, in Churchill, Manitoba. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

A person walks along the rocks near Hudson Bay while watching for polar bears, Saturday, Aug. 3, 2024, in Churchill, Manitoba. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Conservation officer Sgt. Ian Van Nest scans the area for polar bears, Tuesday, Aug. 6, 2024, in Churchill, Manitoba. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

A female polar bear sits on rocks, Wednesday, Aug. 7, 2024, in Churchill, Manitoba. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)