WELLINGTON, New Zealand (AP) — A proposed law that would redefine New Zealand’s founding treaty between the British Crown and Māori chiefs has triggered political turmoil and a march by thousands of people the length of the country to Parliament to protest it.

The bill is never expected to become law. But it has become a flashpoint on race relations and a critical moment in the fraught 180-year-old conversation about how New Zealand should honor its promises to Indigenous people when the country was colonized -– and what those promises are.

Tens of thousands are expected to throng the capital, Wellington, for the final stretch of the weeklong protest march on Tuesday. It follows a Māori tradition of hīkoi, or walking, to bring attention to breaches of the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi.

Considered New Zealand’s founding document, the treaty was signed between representatives of the British Crown and 500 Māori chiefs during colonization. It laid out principles guiding the relationship between the Crown and Māori, in two versions -– one in English and the other in Māori.

It promised Māori the rights and privileges of British citizens, but the English and Māori versions differed on what power the chiefs were ceding over their affairs, lands and autonomy.

Over decades, the Crown breached both versions. By the mid-20th century, Māori language and culture had dwindled -– Indigenous people were often barred from practicing it -- tribal land was confiscated and Māori were disadvantaged in many metrics.

Prompted by a surging Māori protest movement, for the past 50 years the courts of New Zealand, lawmakers and the Waitangi Tribunal -– a permanent body set up to adjudicate treaty matters -– have navigated the differences in the treaty’s versions and tried to redress breaches by constructing the meaning of the treaty's principles in their decisions.

Those principles are intended to be flexible but are commonly described as partnership with the Crown, protection of Māori interests and participation in decision-making.

While Māori remain disenfranchised in many ways, the weaving of treaty recognition through law and attempts at redress have changed the fabric of society since then. Māori language has experienced a renaissance, and everyday words are now commonplace -– even among non-Māori. Policies have been enacted to target disparities Māori commonly face.

Billions of dollars in settlements have been negotiated between the Crown and tribes for breaches of the treaty, particularly the widespread expropriation of Māori land and natural resources.

Some New Zealanders, however, are unhappy with redress. They have found a champion in lawmaker David Seymour, the leader of a minor libertarian political party which won less than 9% of the vote in last year’s election -– but scored outsized influence for its agenda as part of a governing agreement.

Seymour‘s proposed law would set specific definitions of the treaty’s principles, and would apply them to all New Zealanders, not only to Māori. He says piecemeal construction of the treaty’s meaning has left a vacuum and has given Māori special treatment.

His bill is widely opposed — by left- and right-wing former prime ministers, 40 of the country’s most senior lawyers, and thousands of Māori and non-Māori New Zealanders who are walking the length of the country in protest.

Seymour’s bill is not expected to pass its final reading. It cleared a first vote on Thursday due to a political deal, but most of those who endorsed it are not expected to do so again.

Detractors say the bill threatens constitutional upheaval and would remove rights promised in the treaty that are now enshrined in law. Critics have also lambasted Seymour -– who is Māori -– for provoking backlash against Indigenous people.

Peaceful walking protests are a Māori tradition and have occurred before at crucial times during the national conversation about treaty rights.

Police in the country of 5 million people say they expect 30,000 to march across Wellington to Parliament on Tuesday. Crowds of up to 10,000 people have joined the march in cities en route to Wellington.

Many are marching to oppose Seymour’s bill. But others are protesting a range of policies from the center-right government on Māori affairs -– including an order, prompted by Seymour, that public agencies should no longer target policies to specifically redress Māori inequities.

FILE - A protester against the Treaty Principles Bill sits outside Parliament in Wellington, New Zealand, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024. (AP Photo/Charlotte Graham-McLay, File)

FILE - Protesters against the Treaty Principles Bill stand by a Māori sovereignty flag outside Parliament in Wellington, New Zealand, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024. (AP Photo/Charlotte Graham-McLay, File)

FILE - ACT Party leader David Seymour stands during the first debate on the Treaty Principles Bill in Parliament in Wellington, New Zealand, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024. (AP Photo/Charlotte Graham-McLay, File)

FILE - A protester against the Treaty Principles Bill sits outside Parliament in Wellington, New Zealand, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024. (AP Photo/Charlotte Graham-McLay, File)

BAKU, Azerbaijan (AP) — United Nations talks on getting money to curb and adapt to climate change resumed Monday with tempered hope that negotiators and ministers can work through disagreements and hammer out a deal after slow progress last week.

That hope comes from the arrival of the climate and environment ministers from around the world this week in Baku, Azerbaijan, for the COP29 talks. They’ll give their teams instructions on ways forward.

"We are in a difficult place,” said Melanie Robinson, economics and finance program director of global climate at the World Resources Institute. “The discussion has not yet moved to the political level — when it does I think ministers will do what they can to make a deal.”

Talks in Baku are focused on getting more climate cash for developing countries to transition away from fossil fuels, adapt to climate change and pay for damages caused by extreme weather. But countries are far apart on how much money that will require. Several experts put the sum needed at around $1 trillion.

“One trillion is going to look like a bargain five, 10 years from now,” said Rachel Cleetus from the Union of Concerned Scientists, citing a multitude of costly recent extreme weather events from flooding in Spain to hurricanes Helene and Milton in the United States. “We’re going to wonder why we didn’t take that and run with it.”

Also on Monday, the Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development has been mulling a proposal to cut public spending for foreign fossil fuel projects. The OECD — made up of 38 member countries including the United States, the United Kingdom, South Korea, Japan and Germany — are discussing a deal that could prevent up to $40 billion worth of carbon-polluting projects.

At COP29, activists are protesting the U.S., South Korea, Japan, and Turkey who they say are the key holdouts preventing the agreement in Paris from being finalized.

“It’s of critical importance that President Biden comes out in support. We know it’s really important that he lands a deal that Trump cannot undo. This can be really important for Biden’s legacy," said Lauri van der Burg, Global Public Finance Lead at Oil Change international. “If he comes around, this will help mount pressure on other laggards including Korea, Turkey and Japan.”

Meanwhile, the world’s biggest decision makers are halfway around the world as another major summit convenes. Brazil is hosting the Group of 20 summit, which runs Nov. 18-19, bringing together many of the world's largest economies. Climate change — among other major topics like rising global tensions and poverty — will be on the agenda.

Harjeet Singh, global engagement director for the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty Initiative, said G20 nations “cannot turn their backs on the reality of their historical emissions and the responsibility that comes with it.”

"They must commit to trillions in public finance," he said.

In a written statement on Friday, United Nations Climate Change's executive secretary Simon Stiell said “the global climate crisis should be order of business Number One” at the G20 meetings.

Stiell noted that progress on stopping more warming should happen both in and out of climate talks, calling the G20's role “mission-critical.”

Associated Press journalist Ahmed Hatem in Baku contributed to this report.

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Activist Ann Carlotta Oltmanns, center, pretends to resuscitate Earth with others during a demonstration at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Monday, Nov. 18, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Activist Friday Barilule Nbani leads a demonstration for clean energy at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Monday, Nov. 18, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

Mukhtar Babayev, COP29 President, bangs a gavel during a plenary session at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Monday, Nov. 18, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Rafiq Maqbool)

Attendees gather in the Moana Blue Pacific Pavilion at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Monday, Nov. 18, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

Yalchin Rafiyev, Azerbaijan's COP29 lead negotiator, attends a plenary session at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Monday, Nov. 18, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Rafiq Maqbool)

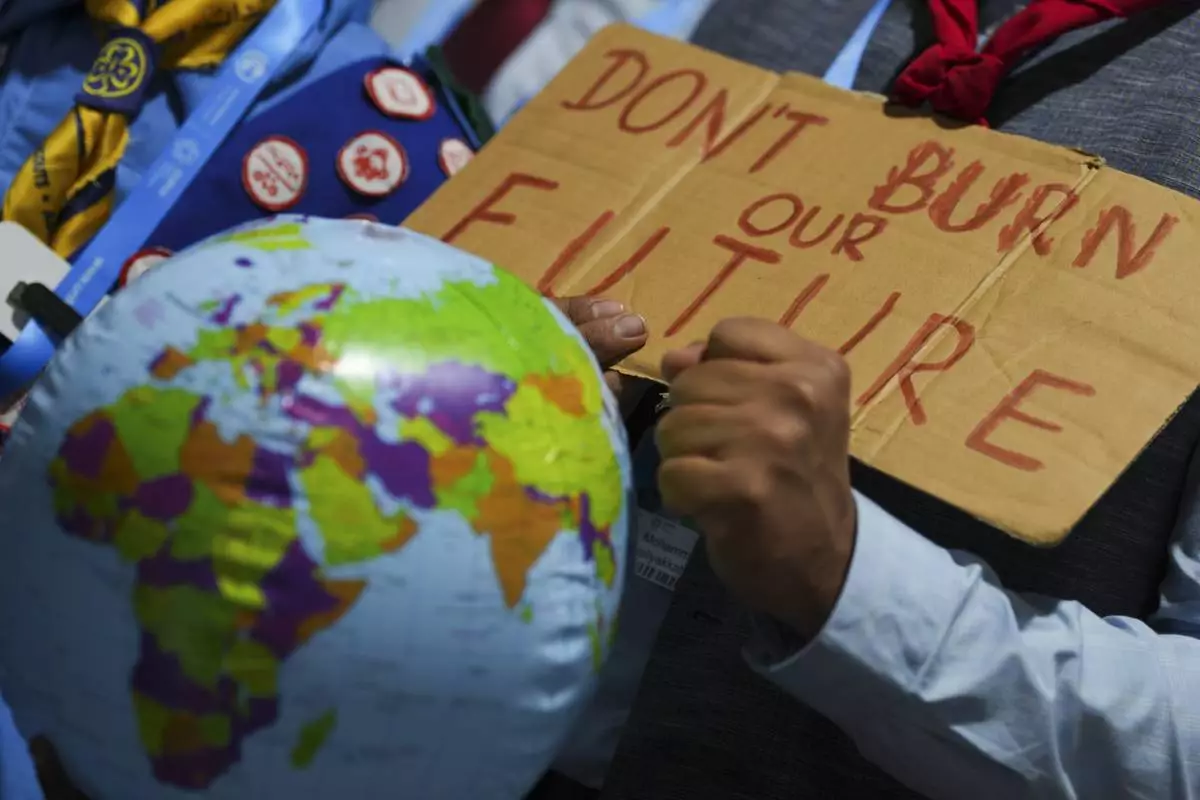

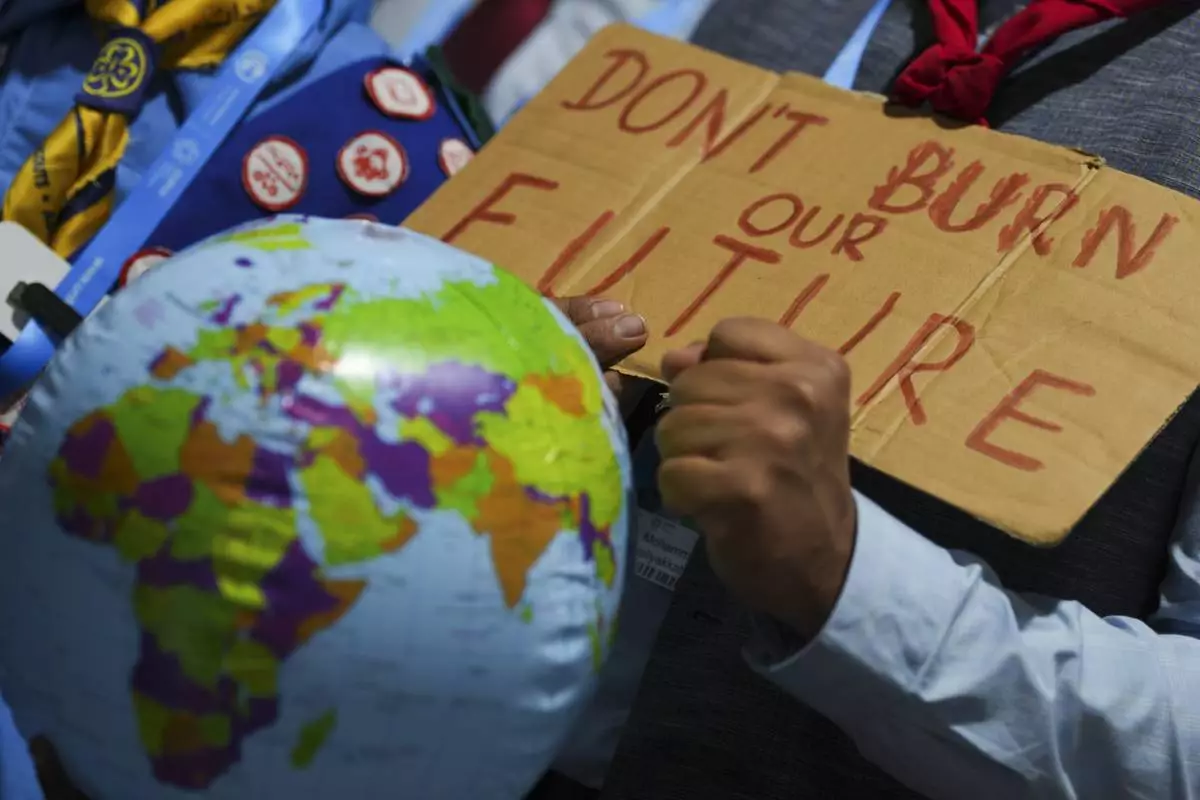

A demonstrators holds a sign that reads "don't burn our future" at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Monday, Nov. 18, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Attendees arrive at the venue as it rains during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Monday, Nov. 18, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

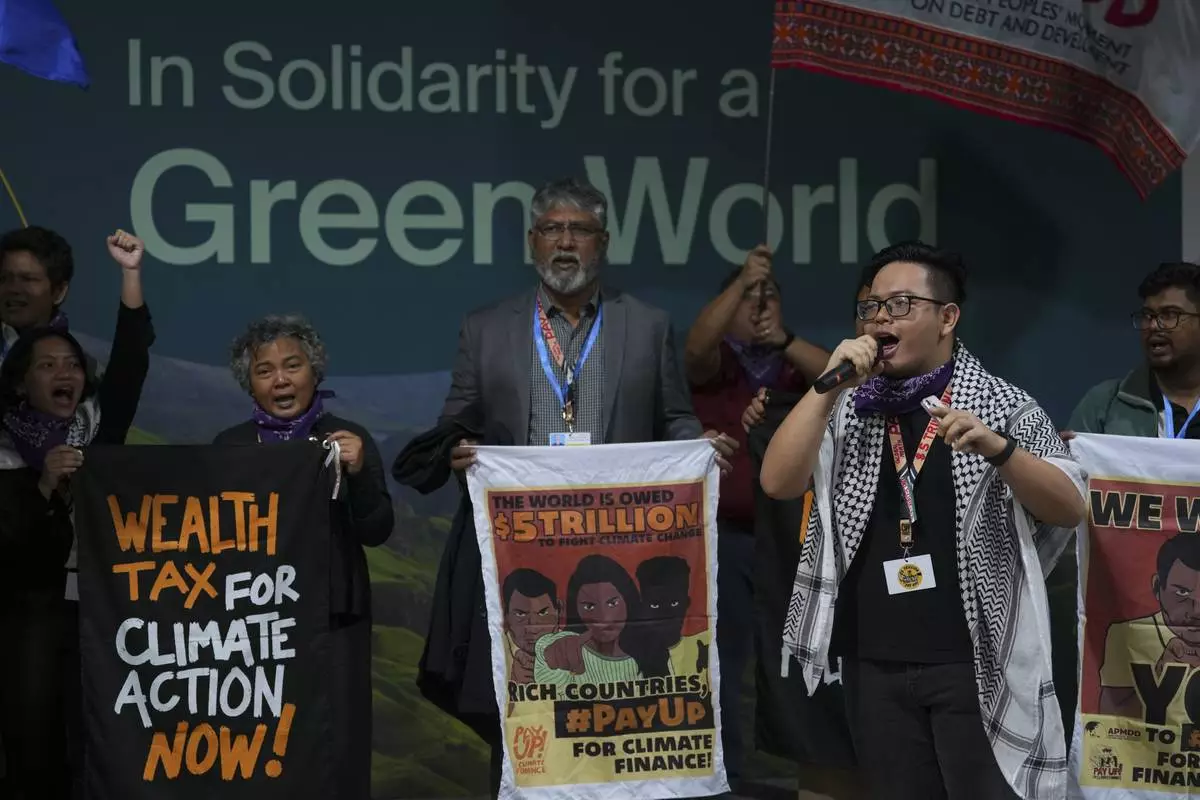

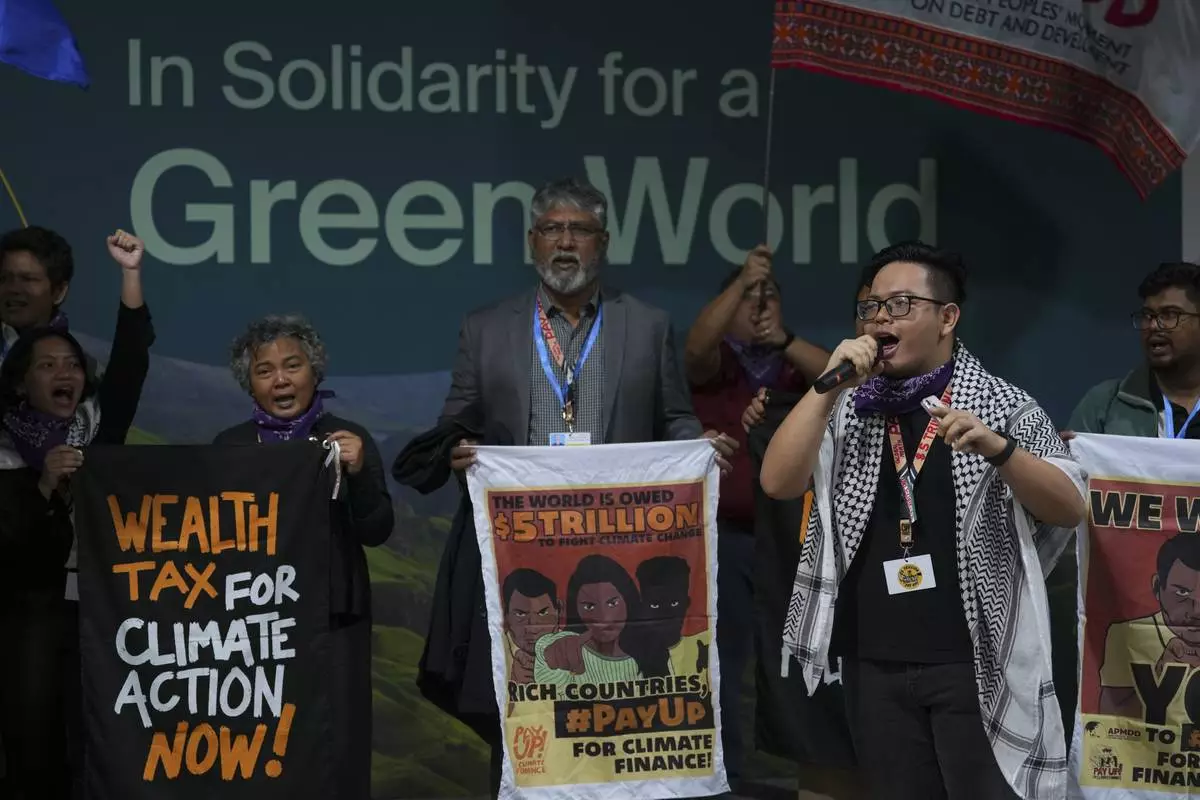

Activists participate in a demonstration for climate finance at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Monday, Nov. 18, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Arnold Jason Del Rosario leads a demonstration on climate finance at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Monday, Nov. 18, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

People arrive as it rains at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Monday, Nov. 18, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Rafiq Maqbool)