After being grounded for months following a crash last November that killed eight service members in Japan, the V-22 Osprey — a complicated aircraft that flies fast like a plane but converts to land like a helicopter — is back in the air.

But there are still questions as to whether it should be.

Click to Gallery

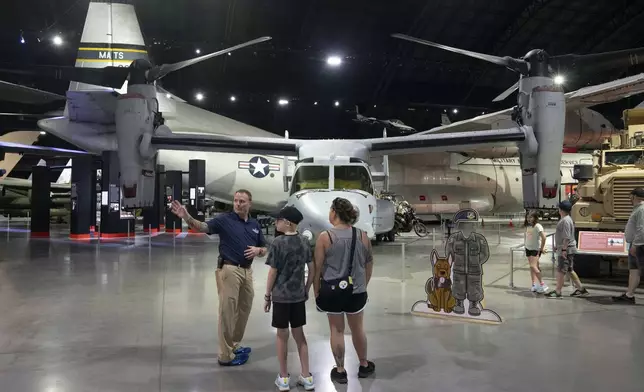

Former Air Force Osprey pilot Brian Luce, left, speaks with museum visitors inside of the Wright Patterson AFB Air Force Museum, Aug. 9, 2024, in Dayton, Ohio. (AP Photo/Jeff Dean)

FILE - Maj. Barry Moore shows a photo of a V-22 Osprey aircraft at a news conference, July 20, 1992, at Quantico Marine Air Station in Quantico, Va., after an experimental V-22 tilt-rotor aircraft crashed into the Potomac River near the air station. (AP Photo/Charles Tasnadi, File)

FILE - Wreckage of a U.S. military MV-22 Osprey is seen in shallow waters off Nago, Okinawa, southern Japan, Dec. 14, 2016, after it crash landed. (Yu Nakajima/Kyodo News via AP, File)

Marine Two, an Osprey tilt-rotor aircraft, with Vice President Kamala Harris and second gentleman Doug Emhoff aboard, lifts from Soldier Field in Chicago, Aug. 23, 2024.(AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin)

Osprey flight engineer Tech Sgt. Brett McGee sits on the back open ramp of the V-22 and holds the aircraft's .50 caliber gun as the crew flies over a New Mexico training range Oct. 9, 2024, near Cannon Air Force Base. (AP Photo/Tara Copp)

Former Air Force Osprey pilot Brian Luce poses for a portrait inside of the Wright Patterson AFB Air Force Museum, Aug. 9, 2024, in Dayton, Ohio. (AP Photo/Jeff Dean)

FILE - A V-22 Osprey tilt rotor aircraft taxi's during a mission in western Iraqi desert, Oct. 13, 2008. (AP Photo/Dusan Vranic, File)

Since the military started flying the aircraft three decades ago, 64 personnel have been killed and 93 injured in crashes. Japan’s military briefly grounded its fleet again late last month after an Osprey tilted violently during takeoff and struck the ground.

To assess its safety, The Associated Press reviewed thousands of pages of accident reports and flight data obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, interviewed more than 50 current and former program officials, crew members and experts, and flew both simulator and real training flights.

The AP found that safety issues have increased in the past five years and that the design of the aircraft itself is directly contributing to many of the accidents.

Yet past and present Osprey pilots — even those who have lost friends in accidents or been in crashes themselves — are some of the aircraft’s greatest defenders. Ospreys have been deployed around the world, rescuing U.S. service personnel from ballistic missiles in Iraq and evacuating civilians in Niger.

“There’s no other platform out there that can do what the V-22 can do,” said former Osprey pilot Brian Luce, who has survived two crashes. “When everything is going well, it is amazing. But when it’s not, it’s unforgiving.”

The AP found that the top three most serious types of incidents rose 46% between 2019 and 2023, while overall safety issues jumped 18% in the same period before the fleet was grounded.

Moreover, the AP found that over the past five years, not only have incidents climbed for both the Marine Corps and Air Force, but that the rise in safety problems largely involved the Osprey’s engine or drive system.

There were at least 35 instances where crews experienced an engine fire, power loss or stall, 42 issues involving the proprotors and at least 72 instances of chipping. That means that the gears inside the transmission or drive system become so stressed they flake off metal chips that can quickly endanger a flight.

The Marine Corps maintains that the Osprey is still one of the safest aircraft in its fleet. Over the past decade, the rate that it experienced the worst type of accident resulting in either death or loss of aircraft was 2.27 for every 100,000 hours of flight. That compares with 5.66 for its other heavy lift helicopter, the CH-53.

Those numbers don’t tell the whole story. The Marines’ three most serious categories of accidents climbed from 2019 to 2023 — even as the number of hours they flew their Ospreys dropped significantly, from 50,807 total hours in fiscal 2019 to 37,670 hours in 2023, according to data obtained by the AP.

The Air Force’s Osprey has a much higher rate of the worst type of accidents per 100,000 flight hours than its other major aircraft, and its accidents have also climbed even as flight hours have dropped.

Experts said the Osprey’s failures have a variety of causes. In the 1980s, when the V-22 was still in early concept for Bell Flight and Boeing, the Marine Corps got to call the shots on the Osprey's final design because it committed to buying most of them. The Marines wanted an aircraft that could carry at least 24 troops and take up the same limited amount of space on a ship deck as the CH-46 helicopter, which the Osprey was replacing.

Those design limitations made the Osprey weigh more than twice as much as the CH-46.

Because of the Osprey’s weight, the blades needed to be longer, but couldn’t be — they would have hit the body of the aircraft or the tower on the ship deck.

As a result, the Osprey’s proprotors — which work as propellers while flying like an airplane and as rotor blades when functioning as a helicopter — are too small in diameter for the aircraft’s weight, which tops out at 60,500 pounds.

To help with weight, the Osprey’s entire engine and transmission bends like an elbow to shift to a vertical position when it flies like a helicopter — and engines don’t like to be vertical.

While designing the engines to rotate vertically helped the Osprey takeoff, it also created dangers that crews still have to mitigate today.

When flying as a helicopter, the engines can’t cool down because they don’t get enough air flow. The hydraulic lines at the joint can wear down, and the aircraft is difficult to maintain.

The Osprey’s first fatal crash in 1992 occurred because pooled fluids spilled back down into the engine as the aircraft converted from flying horizontally like a plane to vertically like a helicopter to land. It caught fire and crashed, killing seven.

A 2000 crash that killed four Marines happened when a worn-down hydraulic line ruptured and the Osprey lost power.

Then there’s dust. When the Osprey hovers in helicopter mode, the air and exhaust it creates can kick up a wall of dust and debris that can get sucked back into the engines, clogging and degrading them.

In 2015, a Marine Corps Osprey hovering for 45 seconds in Hawaii disturbed so much sand and dust that the crew had to abort and try again to land, because they could no longer see. On their second attempt, the Osprey’s left engine stalled and the aircraft dropped flat, killing two Marines.

Pilots face very sensitive instruments that change from working like the controls inside an airplane to operating like those inside a helicopter.

The aircraft’s cockpit is also crammed with messaging and navigation screens, and rows of control buttons. The aircraft is frequently flashing error codes — but crews can get desensitized to them, what one Osprey pilot called the “fatigue of small errors.”

If there are other complications in flight or a pilot is distracted or misses the significance of an aircraft warning light, those mistakes can turn dangerous quickly.

Col. Seth Buckley, commander of the 20th Special Operations Squadron, which flies Ospreys, acknowledged that he puts a lot of pressure on his crews to be perfect for their own safety.

“You have to take that mindset because there are so many things you can do in this aircraft to induce worse problems,” Buckley said.

Former Air Force Osprey pilot Brian Luce, left, speaks with museum visitors inside of the Wright Patterson AFB Air Force Museum, Aug. 9, 2024, in Dayton, Ohio. (AP Photo/Jeff Dean)

FILE - Maj. Barry Moore shows a photo of a V-22 Osprey aircraft at a news conference, July 20, 1992, at Quantico Marine Air Station in Quantico, Va., after an experimental V-22 tilt-rotor aircraft crashed into the Potomac River near the air station. (AP Photo/Charles Tasnadi, File)

FILE - Wreckage of a U.S. military MV-22 Osprey is seen in shallow waters off Nago, Okinawa, southern Japan, Dec. 14, 2016, after it crash landed. (Yu Nakajima/Kyodo News via AP, File)

Marine Two, an Osprey tilt-rotor aircraft, with Vice President Kamala Harris and second gentleman Doug Emhoff aboard, lifts from Soldier Field in Chicago, Aug. 23, 2024.(AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin)

Osprey flight engineer Tech Sgt. Brett McGee sits on the back open ramp of the V-22 and holds the aircraft's .50 caliber gun as the crew flies over a New Mexico training range Oct. 9, 2024, near Cannon Air Force Base. (AP Photo/Tara Copp)

Former Air Force Osprey pilot Brian Luce poses for a portrait inside of the Wright Patterson AFB Air Force Museum, Aug. 9, 2024, in Dayton, Ohio. (AP Photo/Jeff Dean)

FILE - A V-22 Osprey tilt rotor aircraft taxi's during a mission in western Iraqi desert, Oct. 13, 2008. (AP Photo/Dusan Vranic, File)

UDHAGAMANDALAM, India (AP) — Scattered groves of native trees, flowers and the occasional prehistoric burial ground are squeezed between hundreds of thousands of tea shrubs in southern India's Nilgiris region — a gateway to a time before colonization and the commercial growing of tea that reshaped the country's mountain landscapes.

These sacred groves once blanketed the Western Ghats mountains, but nearly 200 years ago, British colonists installed rows upon rows of tea plantations. The few groves that stand today are either protected by Indigenous communities who preserve them for their faith and traditions, or are being grown and tended back into existence by ecologists who remove tea trees from disused farms and plant seeds native to this biodiverse region. It takes decades, but their efforts are finally starting to see results as forests flourish despite ecological damage and wilder weather caused by climate change.

The teams bringing back the forests — home to more than 600 native plants and 150 animal species found only here — know that they still need to work around their neighbors. Nearly everyone in the region's more than 700,000-strong population either farms black, green and white tea or works with the almost 3 million tourists who come to escape the searing heat of the Indian plains.

“In this time of climate change, I think ecological restoration and rewilding is extremely important,” said Godwin Vasanth Bosco, a Nilgiris-based naturalist and restoration practitioner. “What we’re trying to do is to help nature restore itself.”

Environmentalists say industrial-scale tea farming has destroyed the soil’s nutrients and led to conflict with animals like elephants and gaur, or Indian bison, that have little forest left to live in.

Estimates say nearly 135,000 acres of tea have been planted across the mountains, damaging close to 70% of native grasslands and forests.

“There is no biological diversity," Gokul Halan, a Nilgiris-based water expert, said of the tea farms. “It doesn’t support the local fauna nor is it a food source.”

The forests among the tea farms are recognized by the United Nations as one of the world’s eight “ hottest hotspots for biodiversity,” but the areas degraded by excessive pesticide use and other commercial farming methods have been dubbed “green deserts” by environmentalists for their poor soil and inability to support other life.

The Nilgiris region has also had to clear land to facilitate the increasing number of tourists and people from India’s plains who are moving to the region.

Poorer land makes it more vulnerable to landslides and flooding, which are now more common because of human-caused climate change. The neighboring mountainous region of Wayanad suffered devastating landslides that killed nearly 200 people earlier this year, and Halan warns Nilgiris may suffer a similar fate.

Halan also warned the region is susceptible to long droughts and excess heat because of climate change, and that's already affected some tea harvests.

In a small mountain fold just a few hundred meters below the region’s tallest peak, native trees planted 10 years ago have grown up to 4.5 meters (15 feet) tall. A stream flows amid the young trees that replaced nearly 7 acres of tea plants.

“This whole place was tea plantations and this stream was not flowing throughout the year,” said Bosco, the ecologist. “Since we began our restoration work, it flows through the year and the trees and bamboo have grown well along the stream.”

The forests are known as Shola-grassland forests or cloud forests because they can capture moisture from high-altitude mist.

Bosco said the plants and trees have an “incredible capacity to provide for life” across the nearly 2,000 acres his organization works to restore. The native trees maintain the microclimate underneath them by providing nutrients to the soil. That helps saplings and small plants grow even during hot, dry summers.

The region is also home to several Indigenous communities, called Adivasi, many of them classified as highly vulnerable with only a few thousand of their people remaining.

Representatives of these Adivasi communities consider themselves the original custodians of the forests and have also restored forests in the region. They say such restoration initiatives are welcome.

“When the British built tea estates, we were kicked out to the fringes of this district, our lands were lost and we lost our traditions because of deforestation,” said Mani Raman, who belongs to the Alu Kurumbar Adivasi community.

“Such restoration work is good. By bringing the forests back, the wildlife and birds will get more food. Animals that have moved out of forests will have a place to live,” he said.

Tea growers and factory owners say that the region's entire economy depends on tea and it is relatively less harmful to the local environment compared to rampant development to cater to tourism.

“To convert tea to grasslands and shola forests will have a negative impact on the region’s economy and environment,” said A. Balakrishnan, the owner of a two-year-old tea factory near the town of Kotagiri in the Nilgiris.

Eighty-year-old I. Bhojan, who's been a tea grower all his life, agrees. “There is no Nilgiris without tea,” he said.

Bhojan, president of the small farmers and tea growers welfare association for the Nilgiris, estimates that around 600,000 people — 50,000 of them small farmers — depend on tea for their livelihood.

Balakrishnan argued that tea plants are maintained well given their economic benefits compared to native forests.

“If tea was not there, Nilgiris will become a place for tourists only, there'll be more construction and urbanization,” he said.

Planting woody trees and shrubs in tea plantations, known as agroforestry, can ease the battle for space between farms and restoration, according to some experts.

Other crops and timber "can make tea plantations a bit more biodiverse compared to what is there currently,” said water expert Halan.

Officials of Tamil Nadu state, of which the Nilgiris district is a part, earmarked $24 million earlier this year to encourage farmers to shift away from chemical-laden fertilizers to help preserve soil health. The state's forest department officials also announced plans last year to plant nearly 60,000 native trees in the region.

Restoration ecologist Bosco said adding value to smaller tea farming operations by growing special, higher-quality tea on smaller parcels of land can open up more land to reforestation without hurting farmers' pockets.

He added that if those working to restore the land were paid for that service, that could be another stream of revenue for residents, as well as sourcing new products to sell from the native plants. “For example, we're trying to come up with products from some of the plants that have medicinal value,” he said.

Raman added that future such work could also learn from Adivasi traditional practices.

“Adivasi people have been protecting forests for so long, wherever we live the forests are protected," he said. “The state government should be taking such work up at large scale.”

Follow Sibi Arasu on X at @sibi123

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Motorists ride through the Shola-grassland forests or cloud forests in Nilgiris district, India, Wednesday, Sept. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Aijaz Rahi)

Tea workers disembark from a truck filled with sacks of tea leaves collected from an estate in Nilgiris district, India, Thursday, Sept. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Aijaz Rahi)

Mist covers the tea estates over a thickly populated area in Udhagamandalam in Nilgiris district, India, Thursday, Sept. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Aijaz Rahi)

Tea leaves are processed on a conveyer belt at a tea factory in Nilgiris district, India, Thursday, Sept. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Aijaz Rahi)

Steam rises as tea leaves are processed on a conveyer belt at a tea factory in Nilgiris district, India, Thursday, Sept. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Aijaz Rahi)

Tea leaves are processed at a tea factory in Nilgiris district, India, Thursday, Sept. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Aijaz Rahi)

R. Veeramani, a worker at a tea factory, holds up a bunch of leaves during the withering process in Nilgiris district, India, Thursday, Sept. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Aijaz Rahi)

Workers carry sacks of tea leaves before handing over to a contractor at a tea estate in Nilgiris district, India, Wednesday, Sept. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Aijaz Rahi)

Workers pluck tea leaves using cutters at a tea estate in Nilgiris district, India, Wednesday, Sept. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Aijaz Rahi)

Godwin Vasanth Bosco, a naturalist and restoration practitioner, jumps over a stream where he planted native trees 10 years ago, in Nilgiris district, India, Wednesday, Sept. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Aijaz Rahi)

A worker plucks tea leaves using a cutter at a tea estate in Nilgiris district, India, Wednesday, Sept. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Aijaz Rahi)

Nanjamma, right, part of Adivasi Indigenous community, spends time with children outside her house in Banagudi village, in Nilgiris district, India, Thursday, Sept. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Aijaz Rahi)

Wali, part of Adivasi Indigenous community, carries water collected from a stream in Banagudi village in Nilgiris district, India, Thursday, Sept. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Aijaz Rahi)

The roots of tea plants are visible at a tea estate in Nilgiris district, India, Wednesday, Sept. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Aijaz Rahi)

An Indian giant squirrel rests on a tree branch in the tribal village of Banagudi in Nilgiris district, India, Thursday, Sept. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Aijaz Rahi)

A worker arranges native tree saplings at a nursery run by a restoration practitioner in Udhagamandalam in Nilgiris district, India, Friday, Sept. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Aijaz Rahi)

E. Shekhar, left, and N Krishnan, who work for a restoration practitioner, water the native tree saplings and grasses after planting them at a site surrounded by tea estates, in Nilgiris district, India, Friday, Sept. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Aijaz Rahi)

Workers harvest cabbage from a strip of land surrounded by large tea estates in Nilgiris district, India, Wednesday, Sept. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Aijaz Rahi)

Godwin Vasanth Bosco, a naturalist and restoration practitioner, passes through native trees planted by him 10 years ago in Nilgiris district, India, Wednesday, Sept. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Aijaz Rahi)

A strip of land where native grass species were replanted by a restoration practitioner is surrounded by large tea estates in Nilgiris district, India, Wednesday, Sept. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Aijaz Rahi)

Workers pluck tea leaves using cutters at a tea estate in Nilgiris district, India, Wednesday, Sept. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Aijaz Rahi)