BEIRUT (AP) — Lubnan Baalbaki, the conductor of the Lebanese Philharmonic Orchestra, watched on his phone screen as an aerial camera pointed to a village in southern Lebanon. In seconds, multiple houses erupted into rubble, smoke filling the air. The camera panned right, revealing widespread devastation.

He zoomed in to confirm his fears: His family’s house in the border village of Odaisseh, where his parents are buried, was now in ruins.

Click to Gallery

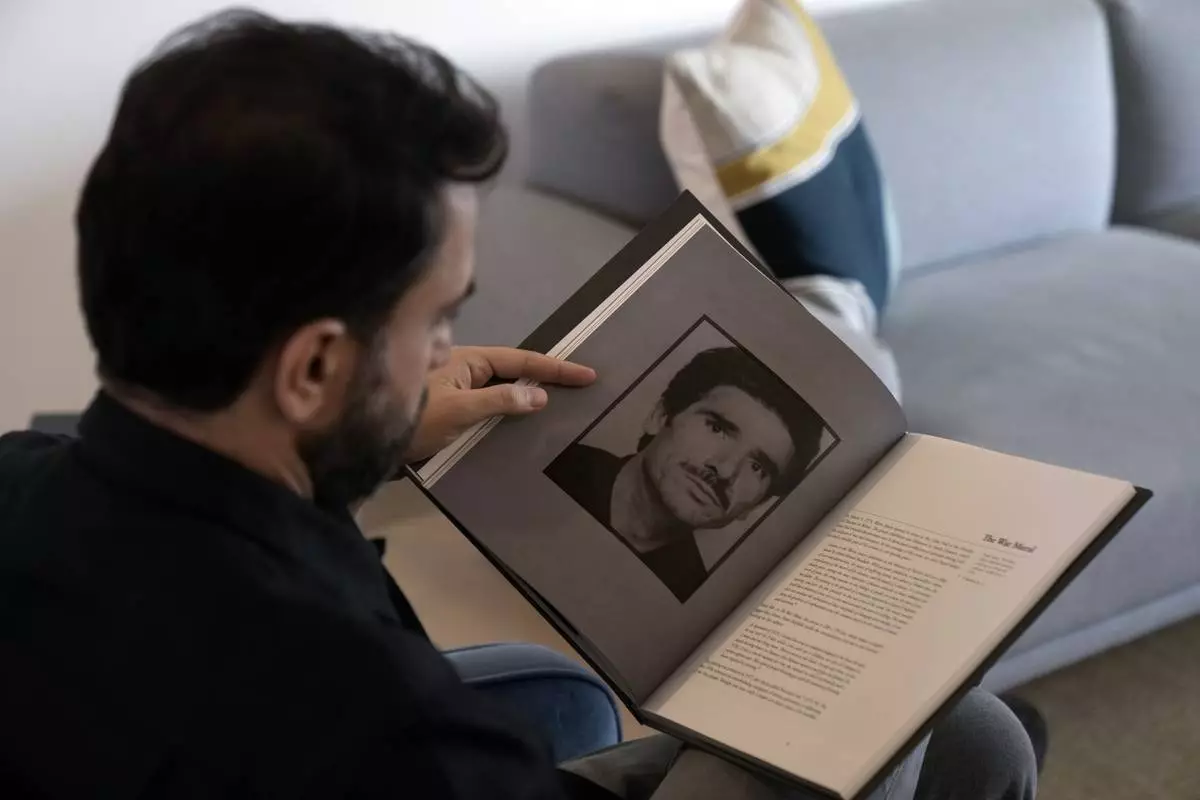

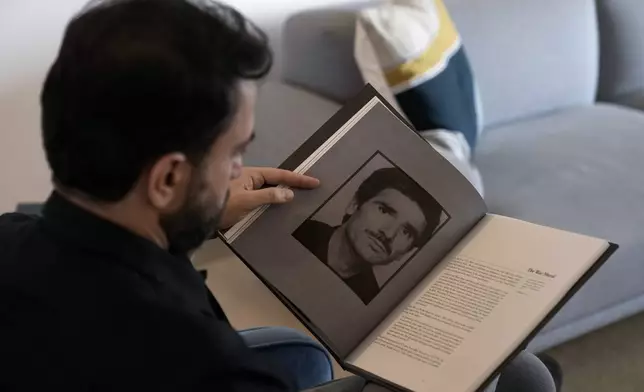

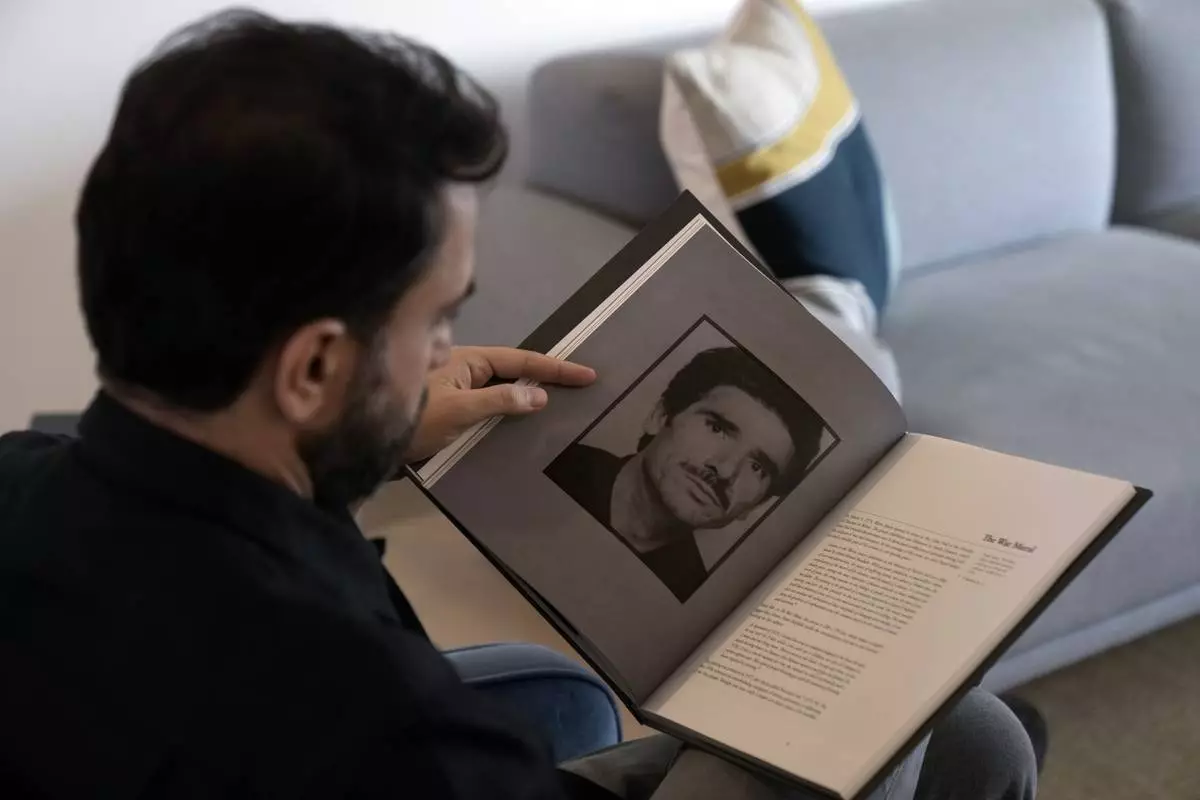

Lubnan Baalbaki shows a picture of his late father during an interview with The Associated Press at his house in Geitawi, Beirut, Lebanon, Thursday, Oct. 31, 2024. (AP Photo/Bilal Hussein)

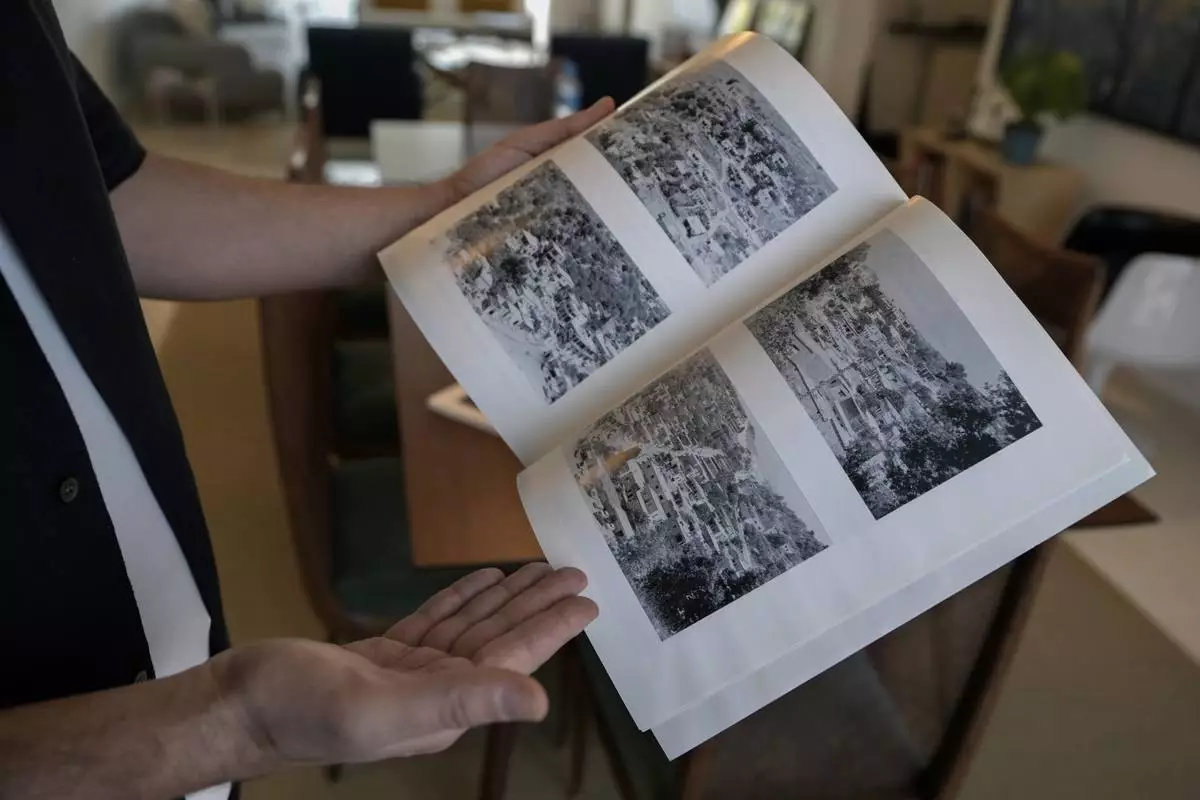

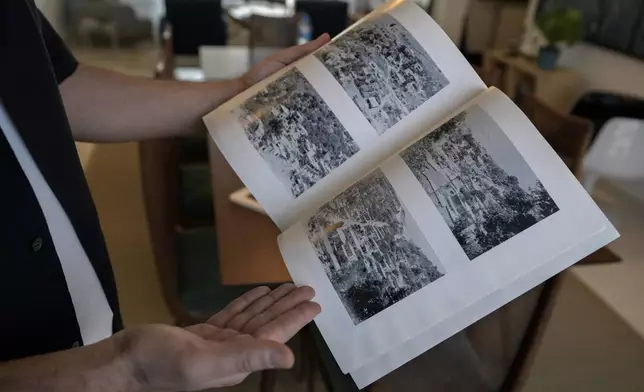

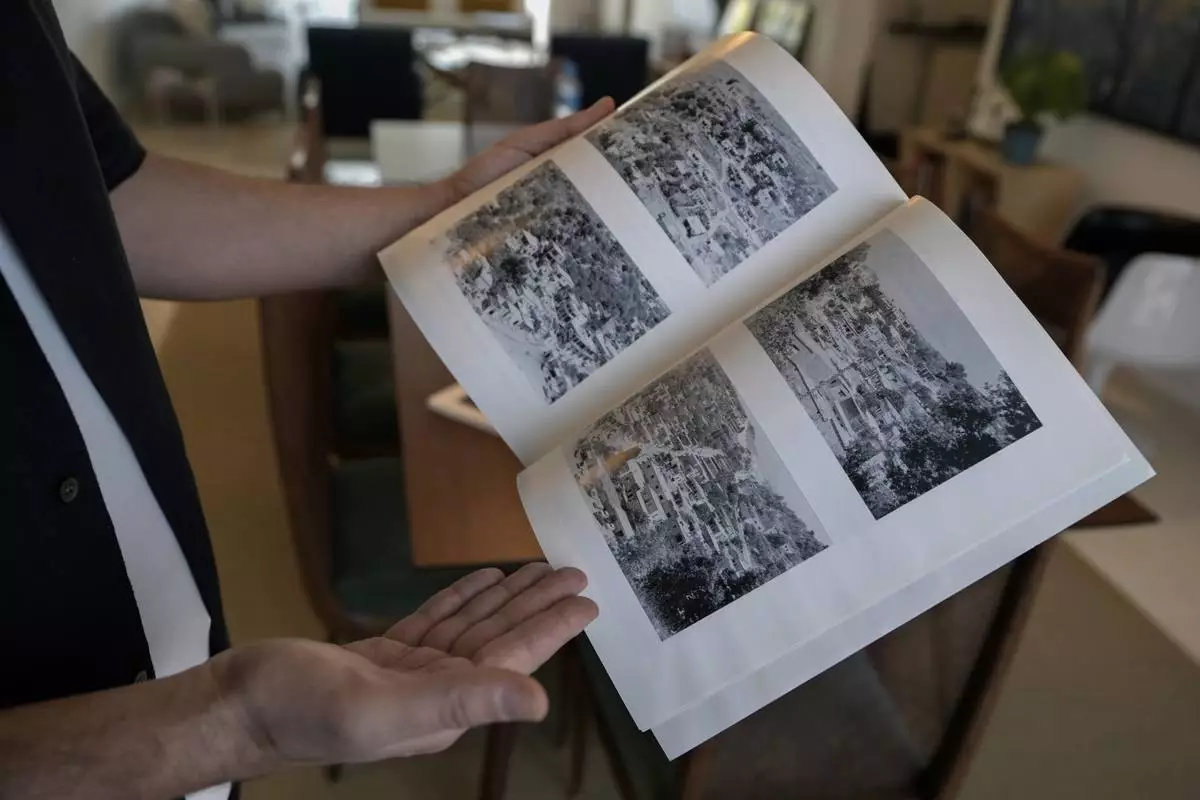

Lubnan Baalbaki shows pictures of Odeisseh village taken by his late father, during an interview with The Associated Press at his house in Geitawi, Beirut, Lebanon, Thursday, Oct. 31, 2024. (AP Photo/Bilal Hussein)

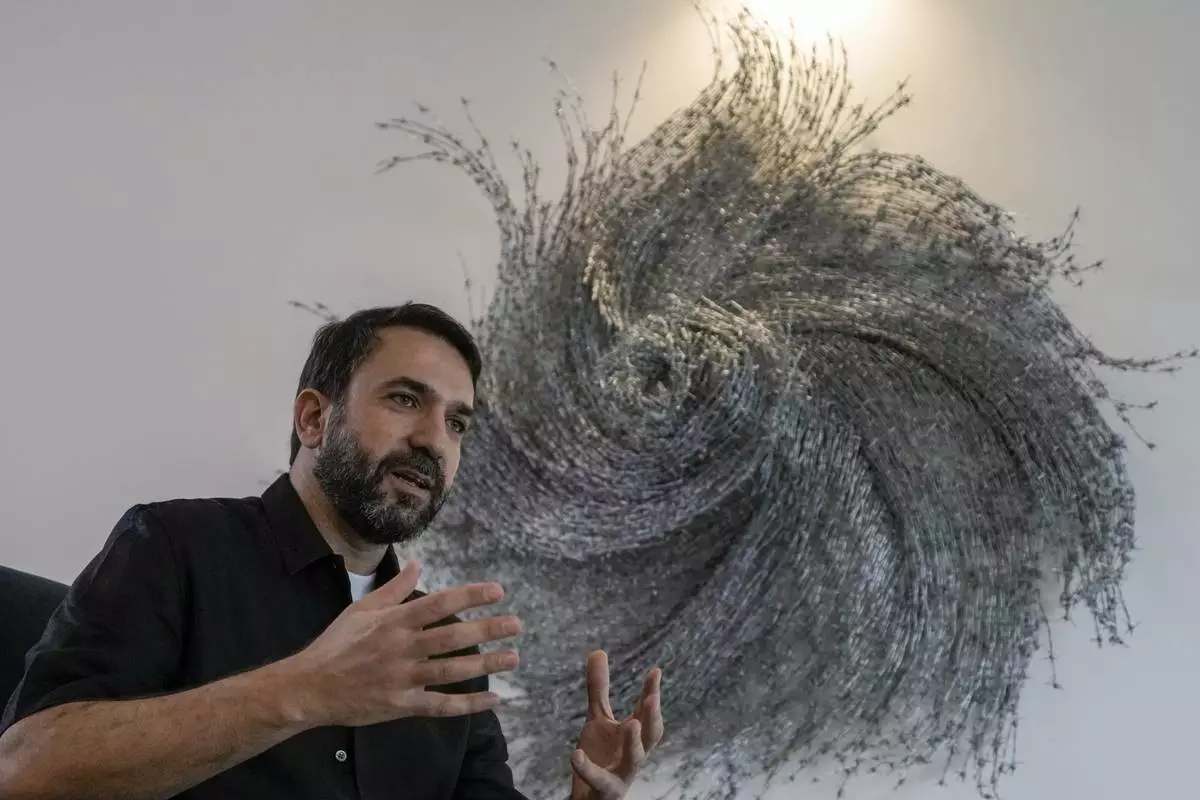

Lubnan Baalbaki shows his father's paintings during an interview with The Associated Press at his house in Geitawi, Beirut, Lebanon, Thursday, Oct. 31, 2024. (AP Photo/Bilal Hussein)

Lubnan Baalbaki shows a sketch depicting him while he was asleep drawn by his late father, during an interview with The Associated Press at his house in Geitawi, Beirut, Lebanon, Thursday, Oct. 31, 2024. (AP Photo/Bilal Hussein)

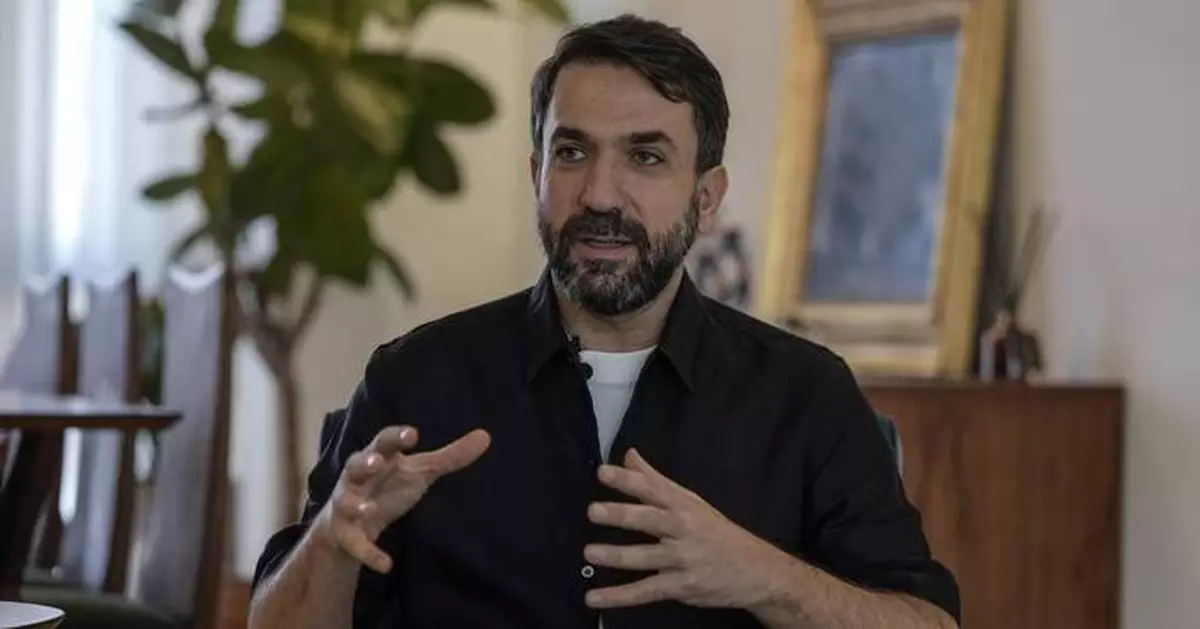

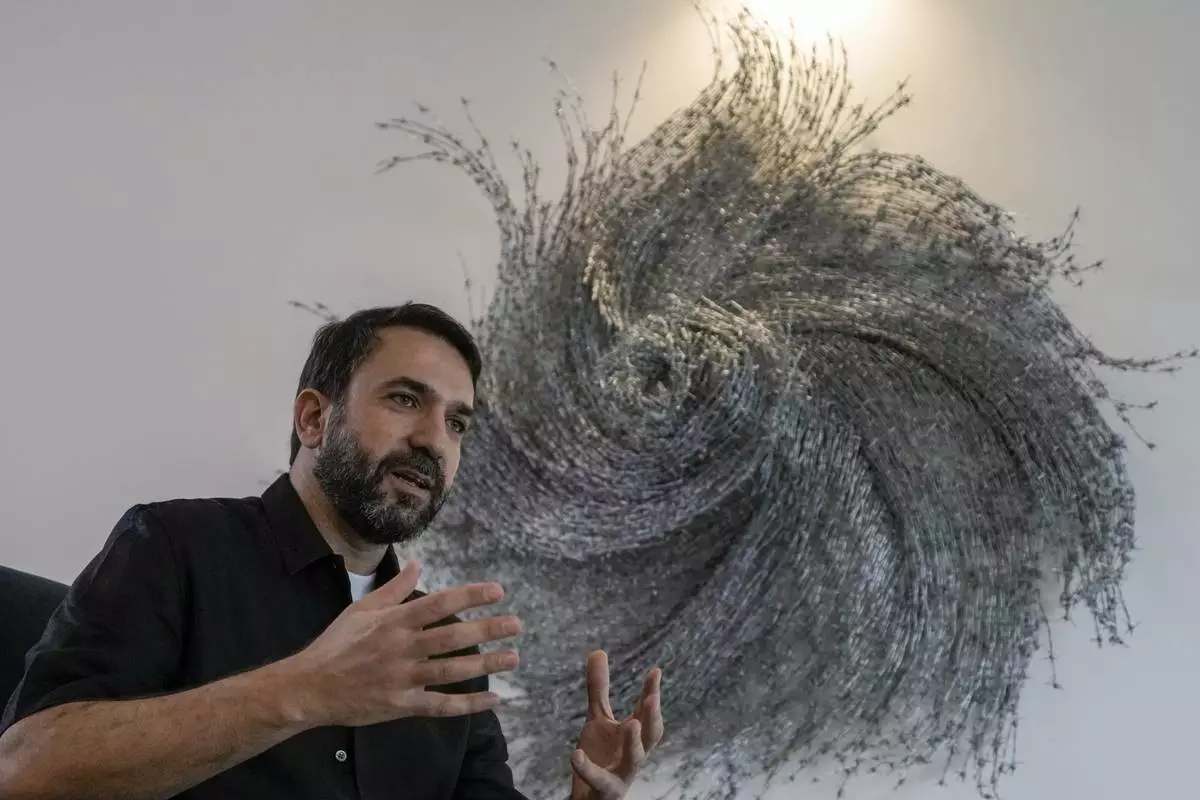

Lubnan Baalbaki speaks during an interview with The Associated Press at his house in Geitawi, Beirut, Lebanon, Thursday, Oct. 31, 2024. (AP Photo/Bilal Hussein)

Lubnan Baalbaki shows a video released by the IDF as they blew up his village of Odeiseh during an interview with The Associated Press at his house in Geitawi, Beirut, Lebanon, Thursday, Oct. 31, 2024. (AP Photo/Bilal Hussein)

Lubnan Baalbaki speaks during an interview with The Associated Press at his house in Geitawi, Beirut, Lebanon, Thursday, Oct. 31, 2024. (AP Photo/Bilal Hussein)

“To see your house getting bombed and in a split second turned into ash, I don’t think there is description for it,” Baalbaki said.

The destruction of his childhood home in October came during Israel's offensive in Lebanon. The aim, Israel says, is to debilitate the Hezbollah militant group, push it away from the border and end more than a year of Hezbollah fire into northern Israel.

The Israeli military has released videos of controlled detonations in areas along the border, saying it is targeting Hezbollah facilities and weapons.

But the bombardment has also wiped out entire residential neighborhoods or even villages. The World Bank in a recent report said over 99,000 housing units have been “fully or partially damaged” by the war in Lebanon.

Baalbaki’s family home in Odaisseh, designed by his late father, renowned Lebanese painter Abdel Hamid Baalbaki, held more than just personal memories. It held a collection of Abdel Hamid’s paintings, his art workshop and over 1,500 books. All were destroyed along with the house.

What cut even deeper, Baalbaki said, was the loss of the letters his parents exchanged during his father’s art studies in France. Only a few remain as digital photos.

“The language of passion and love they shared was filled with poetry,” Baalbaki said.

In a book of poems and photographs his father created for his wife following her sudden death in a car accident, the first page reads, “Dedication to Adeeba, the partner of my most precious days, the love bird that left its nest too soon.”

Abdel Hamid painstakingly designed his wife’s tombstone. Later, he was laid to rest beside her in the garden next to the house. For their son, watching his childhood home go up in smoke brought back the pain of losing them.

It was a moment he had feared for months.

Hezbollah began firing missiles into Israel on Oct. 8, 2023, in solidarity with Hamas in Gaza. Israel responded with airstrikes and shelling. For nearly a year, the conflict remained limited.

After the war dramatically escalated on Sept. 23 with intense Israeli airstrikes on southern and eastern Lebanon as well as Beirut’s southern suburbs, Baalbaki and his siblings frequently checked satellite images for updates on their village.

On Oct. 26, explosions in and around Odaisseh triggered an earthquake alert in northern Israel. That day, videos circulated online, one of which showed their home being obliterated.

Until a few days before that, the satellite images showed their house still standing.

Now, Baalbaki said, he is resolved to honor his father’s dream.

“The mourning phase started to turn to determination to rebuild this project,” he said.

When the war is over, he plans to rebuild the house as an art museum and cultural center.

Lubnan Baalbaki shows a picture of his late father during an interview with The Associated Press at his house in Geitawi, Beirut, Lebanon, Thursday, Oct. 31, 2024. (AP Photo/Bilal Hussein)

Lubnan Baalbaki shows pictures of Odeisseh village taken by his late father, during an interview with The Associated Press at his house in Geitawi, Beirut, Lebanon, Thursday, Oct. 31, 2024. (AP Photo/Bilal Hussein)

Lubnan Baalbaki shows his father's paintings during an interview with The Associated Press at his house in Geitawi, Beirut, Lebanon, Thursday, Oct. 31, 2024. (AP Photo/Bilal Hussein)

Lubnan Baalbaki shows a sketch depicting him while he was asleep drawn by his late father, during an interview with The Associated Press at his house in Geitawi, Beirut, Lebanon, Thursday, Oct. 31, 2024. (AP Photo/Bilal Hussein)

Lubnan Baalbaki speaks during an interview with The Associated Press at his house in Geitawi, Beirut, Lebanon, Thursday, Oct. 31, 2024. (AP Photo/Bilal Hussein)

Lubnan Baalbaki shows a video released by the IDF as they blew up his village of Odeiseh during an interview with The Associated Press at his house in Geitawi, Beirut, Lebanon, Thursday, Oct. 31, 2024. (AP Photo/Bilal Hussein)

Lubnan Baalbaki speaks during an interview with The Associated Press at his house in Geitawi, Beirut, Lebanon, Thursday, Oct. 31, 2024. (AP Photo/Bilal Hussein)

SEOUL, South Korea (AP) — South Korea’s government said Saturday it will not attend a memorial service near Japan’s Sado Island Gold Mines due to unspecified disagreements with Tokyo over the event, which stirred longstanding tensions over the abuse of Korean forced laborers at the site before the end of World War II.

The decision marked a rare display of friction between the countries since the 2022 inauguration of South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol. Yoon has prioritized improving relations with Japan following years of disputes over their bitter history and solidifying three-way security cooperation with Washington to counter North Korean nuclear threats, but has faced accusations at home that he was neglecting the suffering of Korean survivors.

South Korea’s Foreign Ministry said in a statement it was impossible to settle the disagreements between both governments before the planned event near the mines on Sunday. It didn't specify what the disagreements were.

Japanese officials had no immediate comment.

Some South Koreans had criticized Yoon’s government for throwing its support behind an event without securing a clear Japanese commitment to highlight the plight of Korean laborers.

South Korean sentiment over the event worsened after the Japanese government said this week it would send Akiko Ikuina, a parliamentary vice minister at the country’s Foreign Ministry, to the event. Ikuina had reportedly visited Tokyo’s controversial Yasukuni Shrine following her election as a lawmaker in 2022. The shrine honors the country’s about 2.5 million war dead, including convicted war criminals. Japan’s neighbors view the shrine as a symbol of the country’s past militarism.

There were also complaints over South Korea agreeing to pay for the travel expenses of Korean victims’ family members who were invited to attend the ceremony.

Ties between Seoul and Tokyo have long been complicated by grievances related to Japan’s brutal rule of the Korean Peninsula from 1910 to 1945, when hundreds of thousands of Koreans were mobilized as forced laborers for Japanese companies, or sex slaves at Tokyo’s military-run brothels during World War II. Many forced laborers are already dead and survivors are in their 90s.

Historians say hundreds of Koreans were forced to labor at the Sado mines under abusive and brutal conditions during World War II. Japan’s government has said Sunday’s ceremony will pay tribute to “all workers” who died at the mines, without specifying who they are. Critics saw this as part of a persistent policy of whitewashing Japan’s history of sexual and labor exploitation before and during the war.

The 16th-century mines on the island of Sado, off the western coast of Niigata prefecture, operated for nearly 400 years before closing in 1989 and were once the world’s largest gold producer. The mines were designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site earlier this year after Tokyo and Seoul settled a yearslong dispute. South Korea withdrew its opposition to the listing after Japan agreed to acknowledge Korean suffering more clearly in the site’s exhibition and to include Koreans in a memorial ceremony.

In 2023, Yoon took a major step toward improving ties with Japan that had deteriorated for years over historical grievances and trade disputes, by announcing a plan to compensate Korean forced laborers from the colonial period without requiring contributions from Japanese companies.

Yoon’s plan, which relies on money raised in South Korea, drew an immediate backlash at home from former forced laborers and their supporters, who had demanded direct compensation from the Japanese companies and a fresh apology from the Japanese government.

__ AP writer Mari Yamaguchi in Tokyo contributed.

Remains of Japan’s Sado gold mine are seen on Sado Island, northern Japan, on Aug. 19, 2021. (Keiji Uesho/Kyodo News via AP)