NEW YORK (AP) — When John Jobbagy’s grandfather immigrated from Budapest in 1900, he joined a throng of European butchers chopping up and shipping off meat in a loud, smelly corner of Manhattan that New Yorkers called the Meatpacking District.

Today only a handful of meatpackers remain, and they're preparing to say goodbye to a very different neighborhood, known more for its high-end boutiques and expensive restaurants than the industry that gave it its name.

Click to Gallery

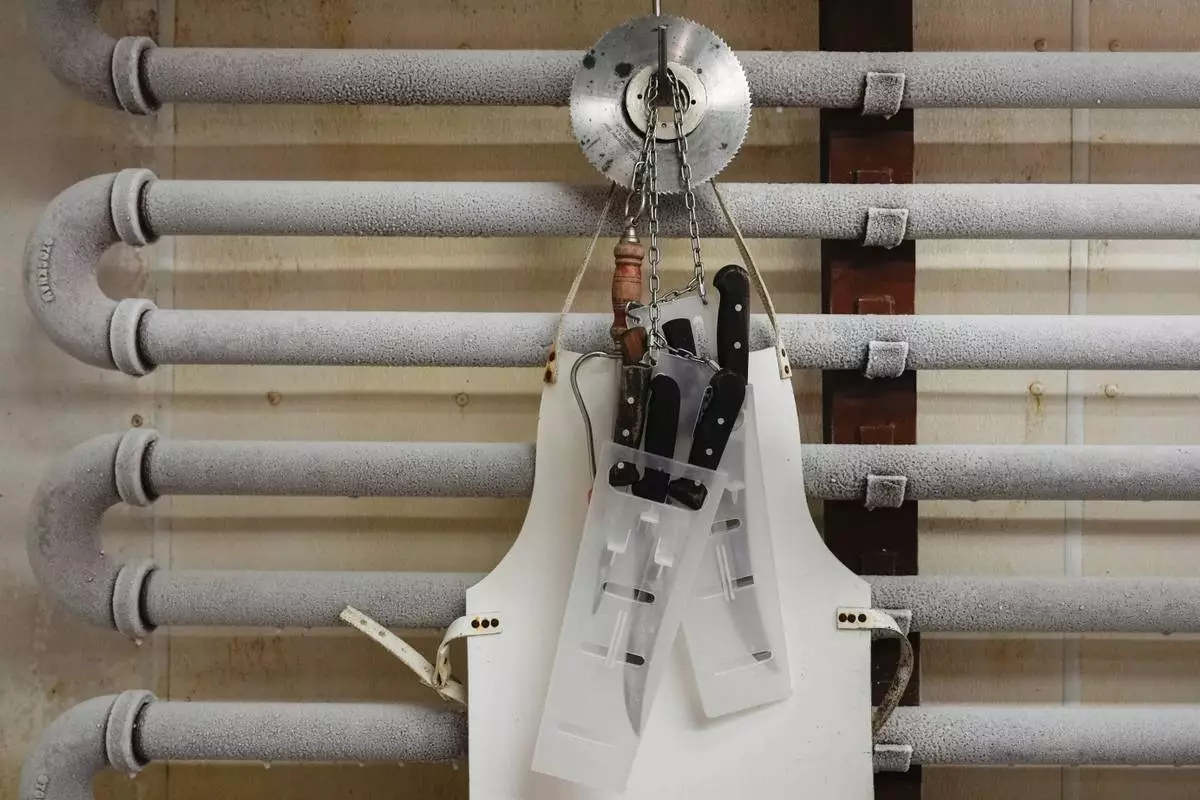

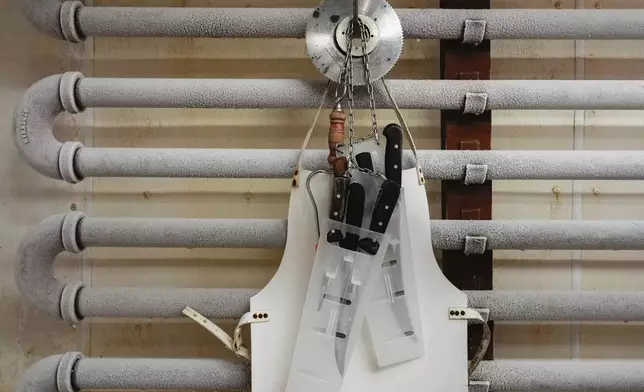

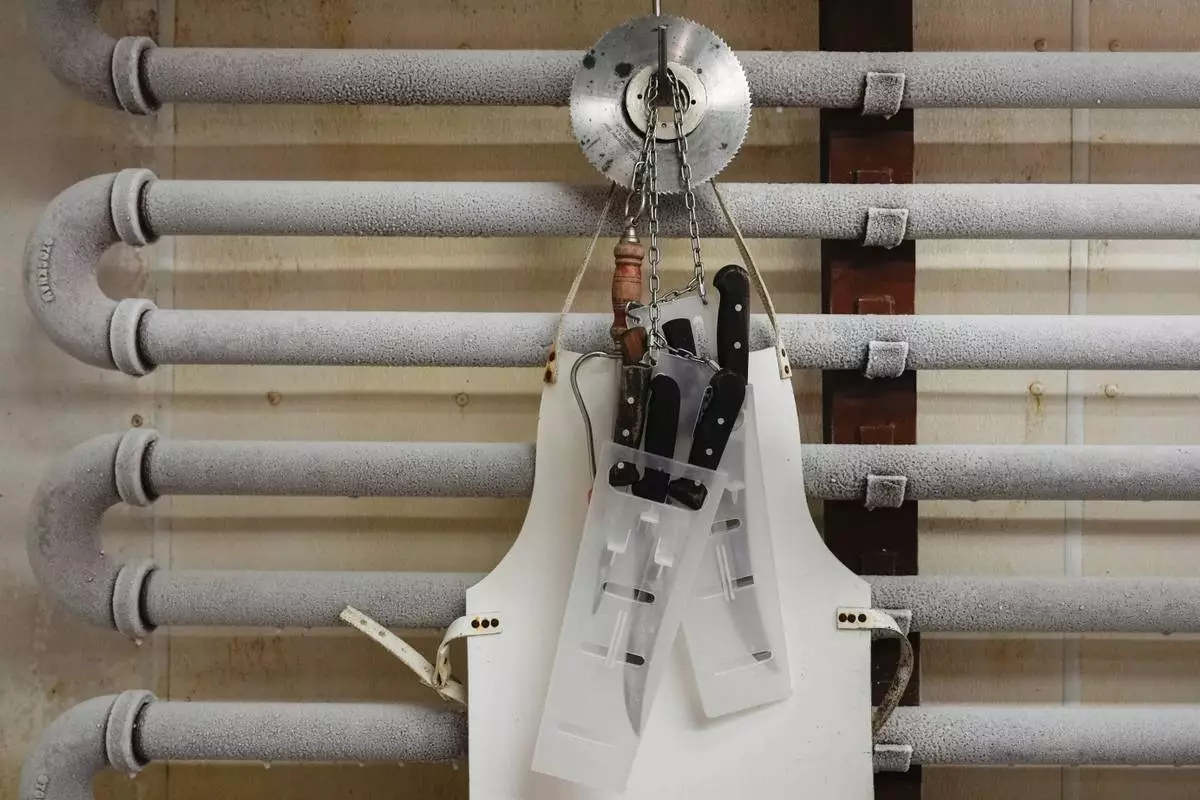

Knifes hang in the meat locker of J.T. Jobbagy Inc. in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

John Jobbagy shows his father in a photograph during an interview with The Associated Press at J.T. Jobbagy Inc. in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

John Jobbagy in his office at J.T. Jobbagy Inc. during an interview in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

John Jobbagy shows cuts of beef in the meat locker of J.T. Jobbagy Inc. during an interview in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

Beef hangs in the meat locker of J.T. Jobbagy Inc. in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

John Jobbagy explains a photo of the Meatpacking District of Manhattan during an interview with The Associated Press at J.T. Jobbagy Inc. in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

The Gansevoort Market and the Whitney Museum of American Art are seen from Little Island park, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

John Jobbagy shows his stamp on a cut of beef during an interview at J.T. Jobbagy Inc. in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

John Jobbagy shows his stamp on a cut of beef during an interview at J.T. Jobbagy Inc. in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

People walk on the High Line in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

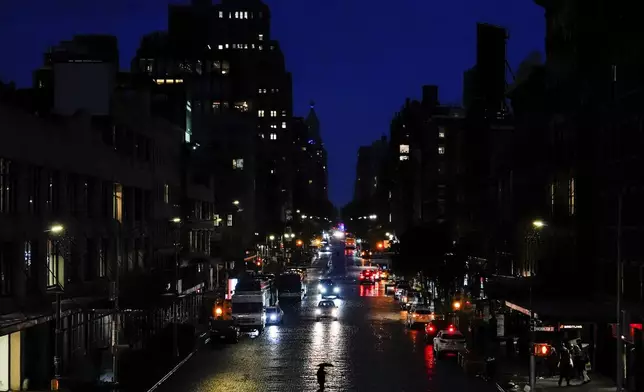

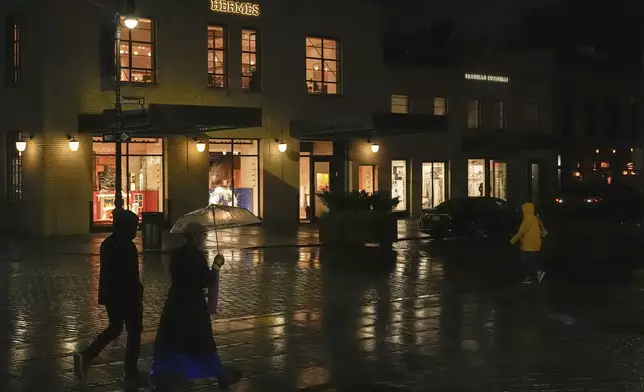

A person uses an umbrella while crossing the street in the Meatpacking District neighborhood of Manhattan, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

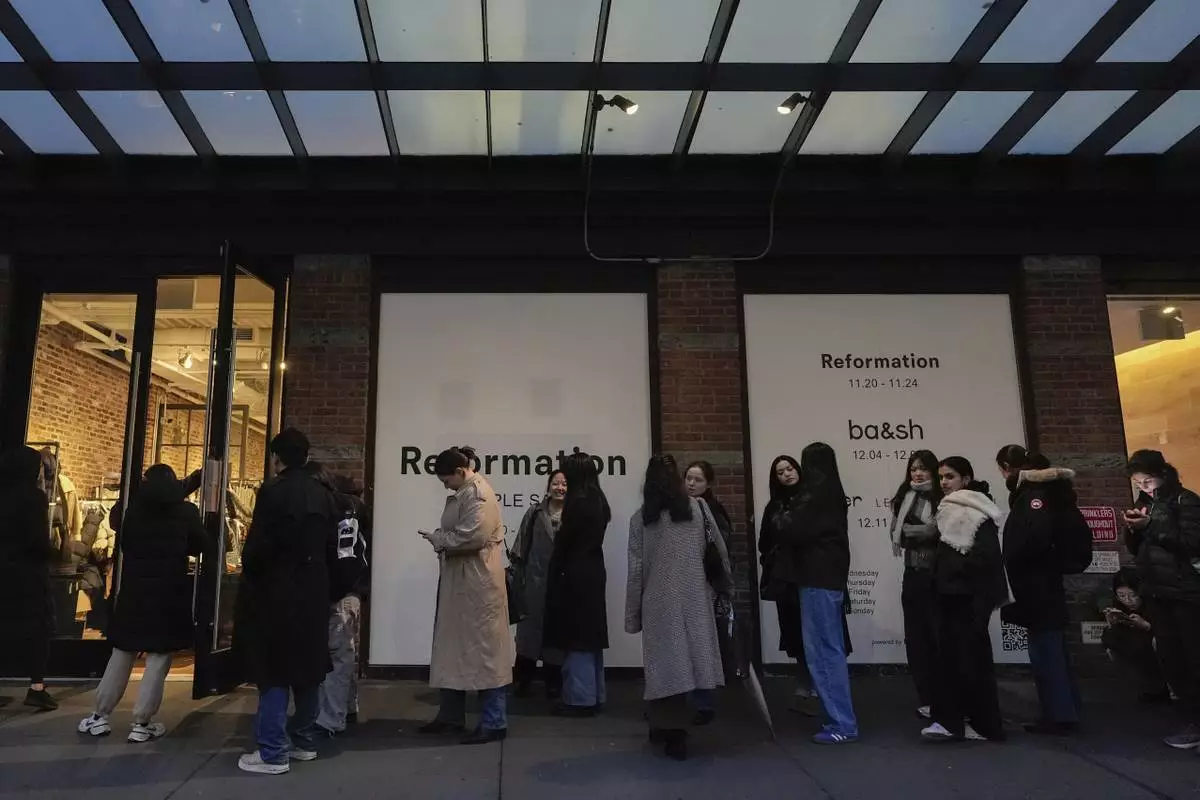

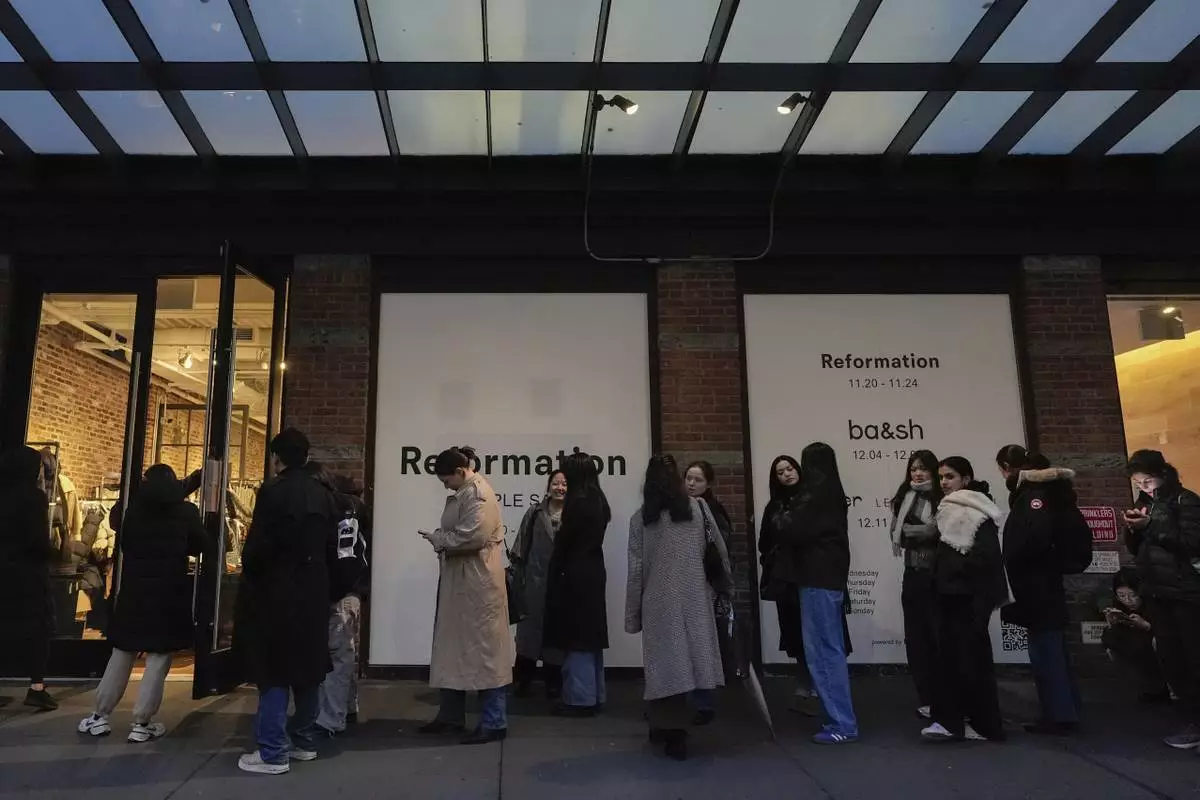

People wait in line for a sample sale in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

This 1937 image from the New York City Municipal Archives shows the Chicken Market, part of New York's Meatpacking District. (New York City Municipal Archives via AP)

This image from the Collections of the New York Public Library shows part of New York's Meatpacking District. (Collections of the New York Public Library via AP)

J.T. Jobbagy Inc. trucks stand under the High Line in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

A Tesla Cybertruck drives through the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

People sit in a bar in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

People wait in line to enter the Whitney Museum of American Art, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

People walk past a Tesla store in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

This Jan. 1929 image from the New York City Municipal Archives shows part of New York's Meatpacking District. (New York City Municipal Archives via AP)

This image from the Collections of the New York Public Library shows part of New York's Meatpacking District, and the construction of the High Line Railway, right. (Collections of the New York Public Library via AP)

An elevated view of the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

John Jobbagy eats at Hector's Cafe & Diner in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

Diners eat at a restaurant in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

People walk past a Hermes store in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

Beef hangs in the meat locker of J.T. Jobbagy Inc. in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

John Jobbagy shows dry aged beef during an interview at J.T. Jobbagy Inc. in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

Jobbagy and the other tenants in the district’s last meat market have accepted a deal from the city to move out so the building can be redeveloped, the culmination of a decades-long transformation.

“The neighborhood I grew up in is just all memories,” said Jobbagy, 68. “It’s been gone for over 20 years.”

In its heyday, it was a gritty hub of over 200 slaughterhouses and packing plants at the intersection of shipping and train lines, where meat and poultry were unloaded, cut and moved quickly to markets. Now the docks are recreation areas and an abandoned freight line is the High Line park. The Whitney Museum of American Art moved from Madison Avenue next to Jobbagy's meat company in 2015.

Some of the new retailers maintain reminders of the neighborhood’s meat-packing past. At the exposed brick entrance to an outlet of fashion brand Rag & Bone, which sells $300 leather belts, is a carefully restored sign from a previous occupant, “Dave’s Quality Veal,” in red and white hand-painted lettering.

Another sign for a wholesale meat supplier appears on a long building awning outside Samsung’s U.S. flagship phone store.

But the neighborhood no longer sounds, smells or feels like the place where Jobbagy began working for his father in the late 1960s. He worked through high school and college summers before going into business for himself.

Back then, meatpackers kept bottles of whiskey in their lockers to stay warm inside the refrigerated plants. Outside, “it reeked,” he said, especially on hot days near the poultry houses where chicken juices spilled into the streets.

People only visited the neighborhood if they had business, usually transacting in handshake deals, he said.

Slowly but surely, meatpacking plants began closing or moving out of Manhattan as advances in refrigeration and packaging enabled the meat industry to consolidate around packing plants in the Midwest, many of which can butcher and package more than 5,000 steers in a day and ship directly to supermarkets.

Starting in the 1970s, a new nightlife scene emerged as bars and nightclubs moved in, many catering to the LGBTQ+ community. Sex clubs and slaughterhouses coexisted. And as the decades wore on, the drag queens and club kids began giving way to fashion designers and restaurateurs.

By 2000, “Sex and The City” character Samantha had left her Upper East Side apartment for a new home in the Meatpacking District. By the show's final 2003 season, she was outraged to see a Pottery Barn slated to open near a local leather bar.

Another turning point came with the 2009 opening of the High Line, on a defunct rail track originally built in the 1930s. The popular greenway is now flanked by hotels, galleries and luxury apartment buildings.

Jobbagy said his father died five years before the opening and would be baffled at what it looks like now.

“If I told him that the elevated railroad was going to be turned into a public park, he never would have believed it,” he said.

But the area has changed constantly, noted Andrew Berman, executive director of local architectural preservation group Village Preservation.

“It wasn’t always a meatpacking district. It was a sort of wholesale produce district before that, and it was a shipping district before that," Berman said. In the early 1800s, Fort Gansevoort stood there. "So it’s had many lives and it’s going to continue to have new lives.”

Though an exact eviction date for the last meat market has not been set, some of the other companies will relocate elsewhere.

Not Jobbagy, who has held on by supplying high-end restaurants and the few retail stores that still want fresh hanging meat. He’ll retire, along with his brother and his employees, most of them Latino immigrants who trained with him and saved up to buy second homes in Honduras, Mexico or the Dominican Republic. Some want to move to other industries, in other states.

He expects to be the last meatpacker standing when the cleaver finally falls on Gansevoort Market.

“I’ll be here when this building closes, when everybody, you know, moves on to something else," Jobbagy said. “And I’m glad I was part of it and I didn’t leave before.”

Knifes hang in the meat locker of J.T. Jobbagy Inc. in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

John Jobbagy shows his father in a photograph during an interview with The Associated Press at J.T. Jobbagy Inc. in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

John Jobbagy in his office at J.T. Jobbagy Inc. during an interview in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

John Jobbagy shows cuts of beef in the meat locker of J.T. Jobbagy Inc. during an interview in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

Beef hangs in the meat locker of J.T. Jobbagy Inc. in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

John Jobbagy explains a photo of the Meatpacking District of Manhattan during an interview with The Associated Press at J.T. Jobbagy Inc. in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

The Gansevoort Market and the Whitney Museum of American Art are seen from Little Island park, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

John Jobbagy shows his stamp on a cut of beef during an interview at J.T. Jobbagy Inc. in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

John Jobbagy shows his stamp on a cut of beef during an interview at J.T. Jobbagy Inc. in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

People walk on the High Line in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

A person uses an umbrella while crossing the street in the Meatpacking District neighborhood of Manhattan, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

People wait in line for a sample sale in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

This 1937 image from the New York City Municipal Archives shows the Chicken Market, part of New York's Meatpacking District. (New York City Municipal Archives via AP)

This image from the Collections of the New York Public Library shows part of New York's Meatpacking District. (Collections of the New York Public Library via AP)

J.T. Jobbagy Inc. trucks stand under the High Line in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

A Tesla Cybertruck drives through the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

People sit in a bar in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

People wait in line to enter the Whitney Museum of American Art, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

People walk past a Tesla store in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

This Jan. 1929 image from the New York City Municipal Archives shows part of New York's Meatpacking District. (New York City Municipal Archives via AP)

This image from the Collections of the New York Public Library shows part of New York's Meatpacking District, and the construction of the High Line Railway, right. (Collections of the New York Public Library via AP)

An elevated view of the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

John Jobbagy eats at Hector's Cafe & Diner in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

Diners eat at a restaurant in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

People walk past a Hermes store in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

Beef hangs in the meat locker of J.T. Jobbagy Inc. in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

John Jobbagy shows dry aged beef during an interview at J.T. Jobbagy Inc. in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson)

SADO, Japan (AP) — Japan held a memorial ceremony on Sunday near the Sado Island Gold Mines despite a last-minute boycott of the event by South Korea that highlighted tensions between the neighbors over the issue of Korean forced laborers at the site before and during World War II.

South Korea’s absence at Sunday’s memorial, to which Seoul government officials and Korean victims’ families were invited, is a major setback in the rapidly improving ties between the two countries, which since last year have set aside their historical disputes to prioritize U.S.-led security cooperation.

The Sado mines were listed in July as a UNESCO World Heritage site after Japan moved past years of disputes with South Korea and reluctantly acknowledged the mines’ dark history, promising to hold an annual memorial service for all victims, including hundreds of Koreans who were mobilized to work in the mines.

On Saturday, South Korea announced it would not attend the event, saying it was impossible to settle unspecified disagreements between the two governments in time.

Families of Korean victims of the mine accidents were expected to separately hold their own ceremony near the mine at a later date.

Masashi Mizobuchi, an assistant press secretary in Japan’s Foreign Ministry, said Japan has been in communication with Seoul and called the South Korean decision “disappointing.”

The ceremony was held as planned on Sunday at a facility near the mines, where more than 20 seats for Korean attendees remained vacant.

The 16th-century mines on the island of Sado, off Japan’s north-central coast, operated for nearly 400 years before closing in 1989 and were once the world’s largest gold producer.

Historians say about 1,500 Koreans were mobilized to Sado as part of Japan’s use of hundreds of thousands of Korean laborers, including those forcibly brought from the Korean Peninsula, at Japanese mines and factories to make up for labor shortages because most working-age Japanese men had been sent to battlefronts across Asia and the Pacific.

Japan’s government has maintained that all wartime compensation issues between the two countries were resolved under a 1965 normalization treaty.

South Korea had long opposed the listing of the site as World Heritage on the grounds that the Korean forced laborers, despite their key role in the wartime mine production, were missing from the exhibition. Seoul's backing for Sado came as South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol prioritized improving relations with Japan.

The Japanese government said Sunday’s ceremony was to pay tribute to “all workers” who died at the mines, but would not spell out inclusion of Korean laborers — part of what critics call a persistent policy of whitewashing Japan’s history of sexual and labor exploitation before and during the war.

Preparation for the event by local organizers remained unclear until the last minute, which was seen as a sign of Japan’s reluctance to face its wartime brutality.

Japan’s government said on Friday that Akiko Ikuina — a parliamentary vice minister who reportedly visited Tokyo’s controversial Yasukuni Shrine in August 2022, weeks after she was elected as a lawmaker — would attend the ceremony. Japan’s neighbors view Yasukuni, which commemorates 2.5 million war dead including war criminals, as a symbol of Japan's past militarism.

Ikuina belonged to a Japanese ruling party faction of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who led the whitewashing of Japan's wartime atrocities in the 2010s during his leadership.

For instance, Japan says the terms “sex slavery” and “forced labor” are inaccurate and insists on the use of highly euphemistic terms such as “comfort women” and “civilian workers” instead.

South Korean Foreign Minister Cho Tae-yul said Saturday that Ikuina’s Yasukuni visit was an issue of contention between the countries’ diplomats.

“That issue and various other disagreements between diplomatic officials remain unresolved, and with only a few hours remaining until the event, we concluded that there wasn’t sufficient time to resolve these differences,” Cho said in an interview with MBN television.

Some South Koreans had criticized Yoon’s government for supporting the event without securing a clear Japanese commitment to highlight the plight of Korean laborers. There were also complaints over South Korea agreeing to pay for the travel expenses of Korean victims’ family members to Sado.

Kim reported from Seoul, South Korea.

Akiko Ikuina, Parliamentary Vice-Minister for Foreign Affairs, offer a flower on behalf of the government during a memorial ceremony for the Sado Island Gold Mine in Sado, Niigata prefecture, Japan, Sunday, Nov. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Guests offer a flower during a memorial ceremony for the Sado Island Gold Mine in Sado, Niigata prefecture, Japan, as several seats reserved for South Korean guests remained empty Sunday, Nov. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Visitors walk though a tunnel at Sado Kinzan Gold Mine historic site in Sado, Niigata prefecture, Japan, Saturday, Nov. 23, 2024. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

A visitor tries to pick up a gold bar at Sado Kinzan Gold Mine historic site in Sado, Niigata prefecture, Japan, Saturday, Nov. 23, 2024. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Guests offer a moment of silence during a memorial ceremony for the Sado Island Gold Mine in Sado, Niigata prefecture, Japan, Sunday, Nov. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Guests offer a moment of silence during a memorial ceremony for the Sado Island Gold Mine in Sado, Niigata prefecture, Japan, Sunday, Nov. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

People visit remains of a Sado gold mine are seen on Sado Island, northern Japan, on Aug. 26, 2024. (Yasufumi Fujita/Kyodo News via AP)

Guests offer a moment of silence during a memorial ceremony for the Sado Island Gold Mine in Sado, Niigata prefecture, Japan, as several seats reserved for South Korean guests remained empty Sunday, Nov. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Mayor of Sado City Ryugo Watanabe delivers a speech during a memorial ceremony for the Sado Island Gold Mine in Sado, Niigata prefecture, Japan, Sunday, Nov. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Visitors look at display at Sado Kinzan Gold Mine historic site in Sado, Niigata prefecture, Japan, Saturday, Nov. 23, 2024. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)