Last time Donald Trump was president, rumors of immigration raids terrorized the Oregon community where Gustavo Balderas was the school superintendent.

Word spread that immigration agents were going to try to enter schools. There was no truth to it, but school staff members had to find students who were avoiding school and coax them back to class.

Click to Gallery

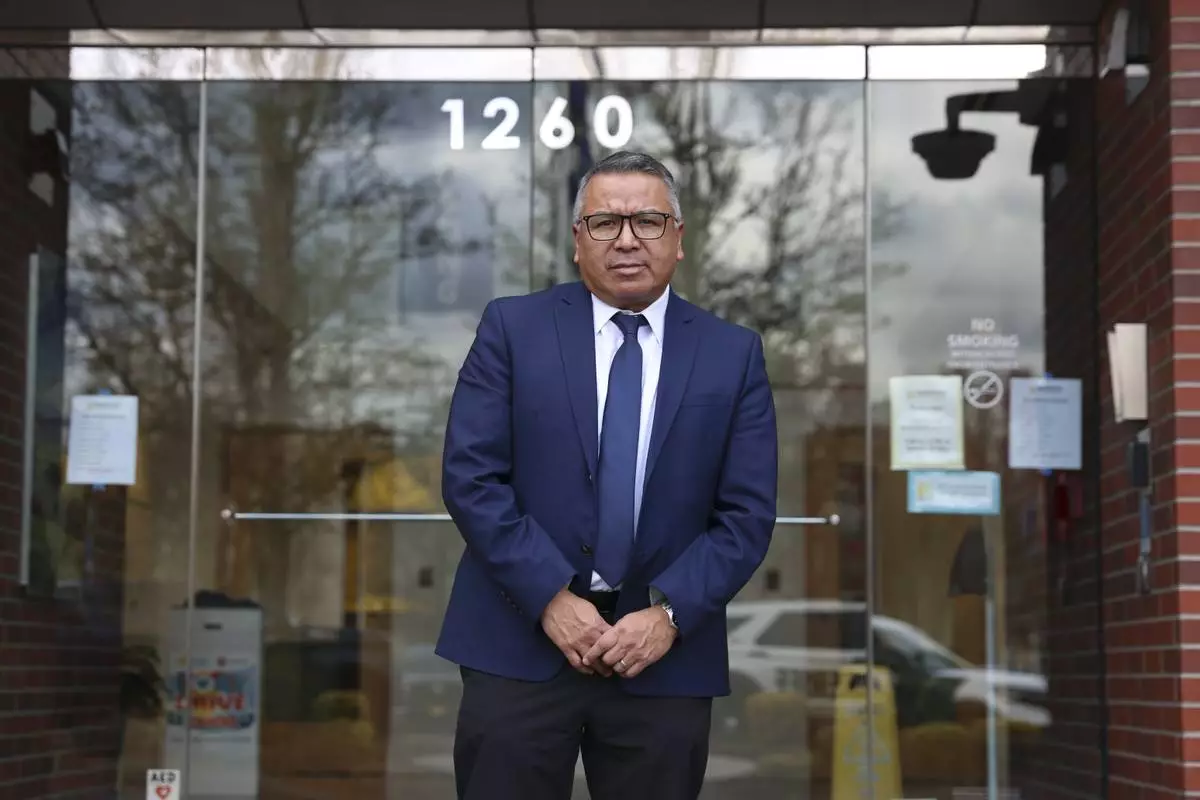

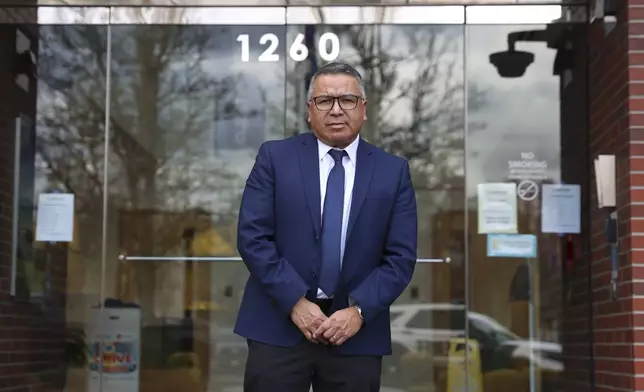

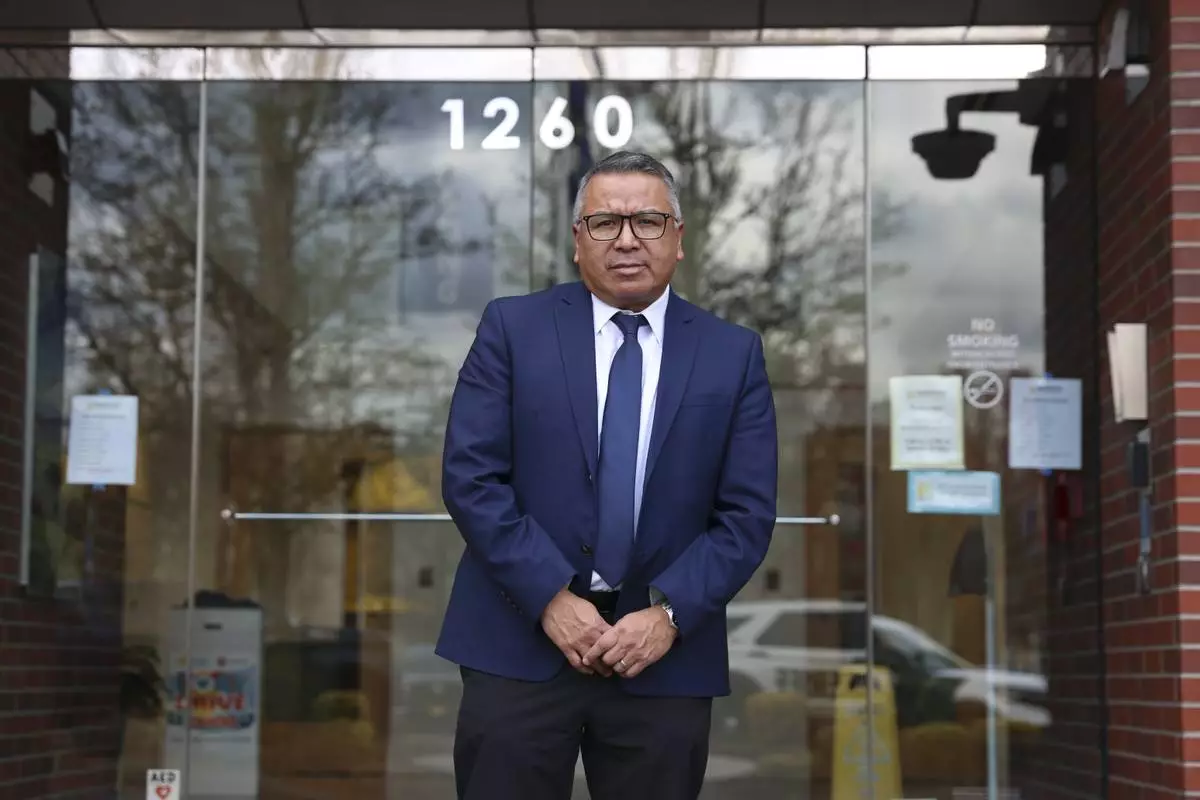

Gustavo Balderas, superintendent of Beaverton School District, stands for a photo in the lobby of the district administrative office in Beaverton, Ore., Monday, Nov. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Amanda Loman)

Gustavo Balderas, superintendent of Beaverton School District, works in his office at the district administrative office in Beaverton, Ore., Monday, Nov. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Amanda Loman)

Gustavo Balderas, superintendent of Beaverton School District, works in his office at the district administrative office in Beaverton, Ore., Monday, Nov. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Amanda Loman)

Gustavo Balderas, superintendent of Beaverton School District, stands for a photo outside of the Beaverton school district administrative office in Beaverton, Ore., Monday, Nov. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Amanda Loman)

Gustavo Balderas, superintendent of Beaverton School District, stands for a photo outside of the Beaverton school district administrative office in Beaverton, Ore., Monday, Nov. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Amanda Loman)

Gustavo Balderas, superintendent of Beaverton School District, stands for a photo outside of the Beaverton school district administrative office in Beaverton, Ore., Monday, Nov. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Amanda Loman)

FILE - Jefferson County Public Schools buses make their way through the Detrick Bus Compound on the first day of school, Aug. 9, 2023, in Louisville, Ky. (Jeff Faughender/Courier Journal via AP, File)

FILE - An American flag hangs in a classroom as students work on laptops in Newlon Elementary School, Aug. 25, 2020, in Denver. (AP Photo/David Zalubowski, File)

“People just started ducking and hiding,” Balderas said.

Educators around the country are bracing for upheaval, whether or not the president-elect follows through on his pledge to deport millions of immigrants who are in the country illegally. Even if he only talks about it, children of immigrants will suffer, educators and legal observers said.

If “you constantly threaten people with the possibility of mass deportation, it really inhibits peoples’ ability to function in society and for their kids to get an education,” said Hiroshi Motomura, a professor at UCLA School of Law.

That fear already has started for many.

“The kids are still coming to school, but they’re scared,” said Almudena Abeyta, superintendent of Chelsea Public Schools, a Boston suburb that’s long been a first stop for Central American immigrants coming to Massachusetts. Now Haitians are making the city home and sending their kids to school there.

“They’re asking: ‘Are we going to be deported?’” said Abeyta.

Many parents in her district grew up in countries where the federal government ran schools and may think it’s the same here. The day after the election, Abeyta sent a letter home assuring parents their children are welcome and safe, no matter who is president.

Immigration officials have avoided arresting parents or students at schools. Since 2011, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement has operated under a policy that immigration agents should not arrest or conduct other enforcement actions near “sensitive locations,” including schools, hospitals and places of worship. Doing so might curb access to essential services, U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas wrote in a 2021 policy update.

The Heritage Foundation's policy roadmap for Trump’s second term, Project 2025, calls for rescinding the guidance on “sensitive places.” Trump tried to distance himself from the proposals during the campaign, but he has nominated many who worked on the plan for his new administration, including Tom Homan for “border czar.”

If immigration agents were to arrest a parent dropping off children at school, it could set off mass panic, said Angelica Salas, executive director of the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights in Los Angeles.

“If something happens at one school, it spreads like wildfire and kids stop coming to school,” she said.

Balderas, now the superintendent in Beaverton, a different Portland suburb, told the school committee there this month it was time to prepare for a more determined Trump administration. In case schools are targeted, Beaverton will train staff not to allow immigration agents inside.

“All bets are off with Trump,” said Balderas, who is also president of ASSA, The School Superintendents Association. “If something happens, I feel like it will happen a lot quicker than last time.”

Many school officials are reluctant to talk about their plans or concerns, some out of fear of drawing attention to their immigrant students. One school administrator serving many children of Mexican and Central American immigrants in the Midwest said their school has invited immigration attorneys to help parents formalize any plans for their children’s care in case they are deported. The administrator spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak to the media.

Speaking up on behalf of immigrant families also can put superintendents at odds with school board members.

“This is a very delicate issue,” said Viridiana Carrizales, chief executive officer of ImmSchools, a nonprofit that trains schools on supporting immigrant students.

She’s received 30 requests for help since the election, including two from Texas superintendents who don’t think their conservative school boards would approve of publicly affirming immigrant students’ right to attend school or district plans to turn away immigration agents.

More than two dozen superintendents and district communications representatives contacted by The Associated Press either ignored or declined requests for comment.

“This is so speculative that we would prefer not to comment on the topic,” wrote Scott Pribble, a spokesperson for Denver Public Schools.

The city of Denver has helped more than 40,000 migrants in the last two years with shelter or a bus ticket elsewhere. It’s also next door to Aurora, one of two cities where Trump has said he would start his mass deportations.

When pressed further, Pribble responded, “Denver Public Schools is monitoring the situation while we continue to serve, support, and protect all of our students as we always have.”

Like a number of big-city districts, Denver’s school board during the first Trump administration passed a resolution promising to protect its students from immigration authorities pursuing them or their information. According to the 2017 resolution, Denver will not “grant access to our students” unless federal agents can provide a valid search warrant.

The rationale has been that students cannot learn if they fear immigration agents will take them or their parents away while they’re on campus. School districts also say these policies reaffirm their students’ constitutional right to a free, public education, regardless of immigration status.

The Associated Press’ education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Gustavo Balderas, superintendent of Beaverton School District, stands for a photo in the lobby of the district administrative office in Beaverton, Ore., Monday, Nov. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Amanda Loman)

Gustavo Balderas, superintendent of Beaverton School District, works in his office at the district administrative office in Beaverton, Ore., Monday, Nov. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Amanda Loman)

Gustavo Balderas, superintendent of Beaverton School District, works in his office at the district administrative office in Beaverton, Ore., Monday, Nov. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Amanda Loman)

Gustavo Balderas, superintendent of Beaverton School District, stands for a photo outside of the Beaverton school district administrative office in Beaverton, Ore., Monday, Nov. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Amanda Loman)

Gustavo Balderas, superintendent of Beaverton School District, stands for a photo outside of the Beaverton school district administrative office in Beaverton, Ore., Monday, Nov. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Amanda Loman)

Gustavo Balderas, superintendent of Beaverton School District, stands for a photo outside of the Beaverton school district administrative office in Beaverton, Ore., Monday, Nov. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Amanda Loman)

FILE - Jefferson County Public Schools buses make their way through the Detrick Bus Compound on the first day of school, Aug. 9, 2023, in Louisville, Ky. (Jeff Faughender/Courier Journal via AP, File)

FILE - An American flag hangs in a classroom as students work on laptops in Newlon Elementary School, Aug. 25, 2020, in Denver. (AP Photo/David Zalubowski, File)

FRAMINGHAM, Mass. (AP) — For the nearly three decades that he was behind bars, Michael Sullivan's mother and four siblings died, his girlfriend moved on with her life and he was badly beaten in several prison attacks.

All for a murder he long insisted he never committed.

Earlier this month, the 64-year-old Sullivan got a degree of justice when a Massachusetts jury ruled that he was innocent of the 1986 murder and robbery of Wilfred McGrath. He was awarded $13 million — though state regulations cap rewards at $1 million for wrongful convictions. The jury also found a state police chemist falsely testified at the trial though his testimony isn't what guaranteed Sullivan's conviction.

It's the latest in a string of convictions that have been overturned in the state in recent years.

“The most important thing is finding me innocent of the murder, expunging it from my record,” said Sullivan, speaking at the Framingham, Massachusetts, office of his lead attorney Michael Heineman. “The money, of course, will be very helpful to me.”

A spokesman for the Massachusetts attorney general said, "We respect the jury’s verdict and are evaluating whether an appeal is appropriate.”

Sullivan was convicted of murder and armed robbery in 1987 after police say McGrath was robbed and beaten and his body dumped behind an abandoned supermarket.

Authorities zeroed in on Sullivan after they learned his sister had been out with McGrath the night before the murder and the two had gone to the apartment she shared with Sullivan. Another suspect in the murder, Gary Grace, implicated Sullivan and had his murder charges dropped. Grace testified at the trial that Sullivan was wearing a purple jacket the night of the murder and a former State Police chemist testified that he found blood on the jacket and a hair consistent with McGrath, not Sullivan's.

Sullivan was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. Grace, meanwhile, pleaded guilty to accessory after a murder, and was sentenced to 6 years. Emil Petrla, who beat McGrath and helped dispose of his body, pleaded to second-degree murder. He was sentenced to life in prison with the possibility of parole but he died in prison.

“I couldn't believe I was convicted of murder,” Sullivan said, recalling prosecutors mentioned the purple jacket five times in their closing argument. “My mother was crying in the courtroom, my brother was crying. I was crying. It was very hard for me and my family.”

Prison would prove a nightmare for Sullivan. He had his nose almost bitten off in one attack and nearly lost an ear in another. And because he was a lifer, the prison system didn't allow him to take any classes to gain much-needed skills

“It’s very hard on a person, especially when you know you’re innocent,” Sullivan said. “And prison is a bad life, you know. Prison is a tough life.”

But in 2011, Sullivan's fortunes changed dramatically.

Sullivan's attorney requested DNA testing — which had not been available for the first trial — that found no blood on the coat. The testing also found substances on the coat did not contain McGrath's DNA and could not determine if the hair found on a jacket belonged to him.

Dana Curhan, a Boston attorney who represented Sullivan from 1992 until 2014 and pushed for the DNA testing, said Sullivan had always told him McGrath's blood wasn't on the jacket. But he was surprised to learn there wasn't any blood, which undermined the prosecutor's argument that Sullivan had beaten McGrath into a “blood pulp.”

“At the prosecutor's closing, he essentially said, 'Hey, if he wasn’t the one who did it, why did they find blood on both of cuffs of the jacket?'” Curhan said. “He kept repeating that. Now, we don’t have any blood nor a DNA match. You would expect someone doing what he was alleged to have done to be covered in blood. There is no blood. That really was the case.”

A new trial was ordered in 2012 and Sullivan was released in 2013. He spent the first six months on home confinement and had to wear an electronic monitoring bracelet for years.

“When I walked out the front door, I was in an emotional state, he said.

In 2014, the Supreme Judicial Court upheld a decision to grant Sullivan a new trial and, in 2019, the state decided against retrying the case. At the time, Middlesex District Attorney Marian Ryan said it was virtually impossible for her office to successfully retry the case against Sullivan given the deaths of some witnesses, and a diminishment of the memories of other potential witnesses.

Sullivan admits he “shut down” after he was released and, to this day, struggles to function in a world that changed dramatically while he was in prison. Before he was arrested, he had worked at a peanut factory and had planned to go to school to become a truck driver and eventually work for his brother who owned a trucking company.

Instead, he left prison with no job prospects and little hope of finding work. He still can't use a computer and mostly helps his sister with odd jobs. His girlfriend, whom he had known since he was 12, would visit him for a decade in prison but eventually “had to go on with her life."

“I’m still really not adjusted to the outside world,” Sullivan said, adding that he spends much of his time with his Yorkshire terrier Buddy and pigeons that he keeps at his sister's house.

“It’s hard for me,” he said. “I don’t go nowhere. I’m scared all the time ... I'm pretty much a loner.”

Sullivan's sister, Donna Faria, said the family “never for a minute” believed that he killed McGrath. They were at the trial in support and would talk with Sullivan twice a week while he was in prison and visit him every few months.

But Faria laments all that Sullivan lost while in prison, noting he “never had kids, never married like the rest of us did.”

“If he didn’t have me, my brother would have been walking the streets like a lot of the homeless people,” Faria said. “It's almost like he don't trust people. If he is around his family, he feels safe. If he is not, he doesn’t.”

These days, Sullivan spends most of his time at Faria's house in Billerica, Massachusetts, and often does her family’s laundry like he did for fellow inmates while in prison. Despite the jury award, Sullivan doesn't expect that his life will change all that much.

Sullivan will treat himself to a new truck but said he wants to save most of the money to ensure his nieces and nephews have what they need when they turn 21. Sullivan hasn't been getting any therapy for the hardship he endured but his attorney Heineman said he plans to ask the court, as part of the judgment, to provide him with therapy and educational services.

“They'll have money. That will make me very happy,” he said. “The most important thing is my nieces and nephews — taking care of them.”

Michael Sullivan, 64, of Lowell, Mass., who was convicted of murder and armed robbery in 1987 and spend years in jail before being ruled innocent, displays one of his pigeons while speaking with a reporter from The Associated Press, at the home of his sister, Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024, in Billerica, Mass. (AP Photo/Steven Senne)

Michael Sullivan, 64, of Lowell, Mass., who was convicted of murder and armed robbery in 1987 and spend years in jail before being ruled innocent, holds his six-year-old Yorkshire terrier "Buddy" while speaking with a reporter from The Associated Press at his attorney's office, Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024, in Framingham, Mass. (AP Photo/Steven Senne)

Michael Sullivan, 64, of Lowell, Mass., who was convicted of murder and armed robbery in 1987 and spend years in jail before being ruled innocent, brings feed to his pigeons at the home of his sister, Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024, in Billerica, Mass. (AP Photo/Steven Senne)

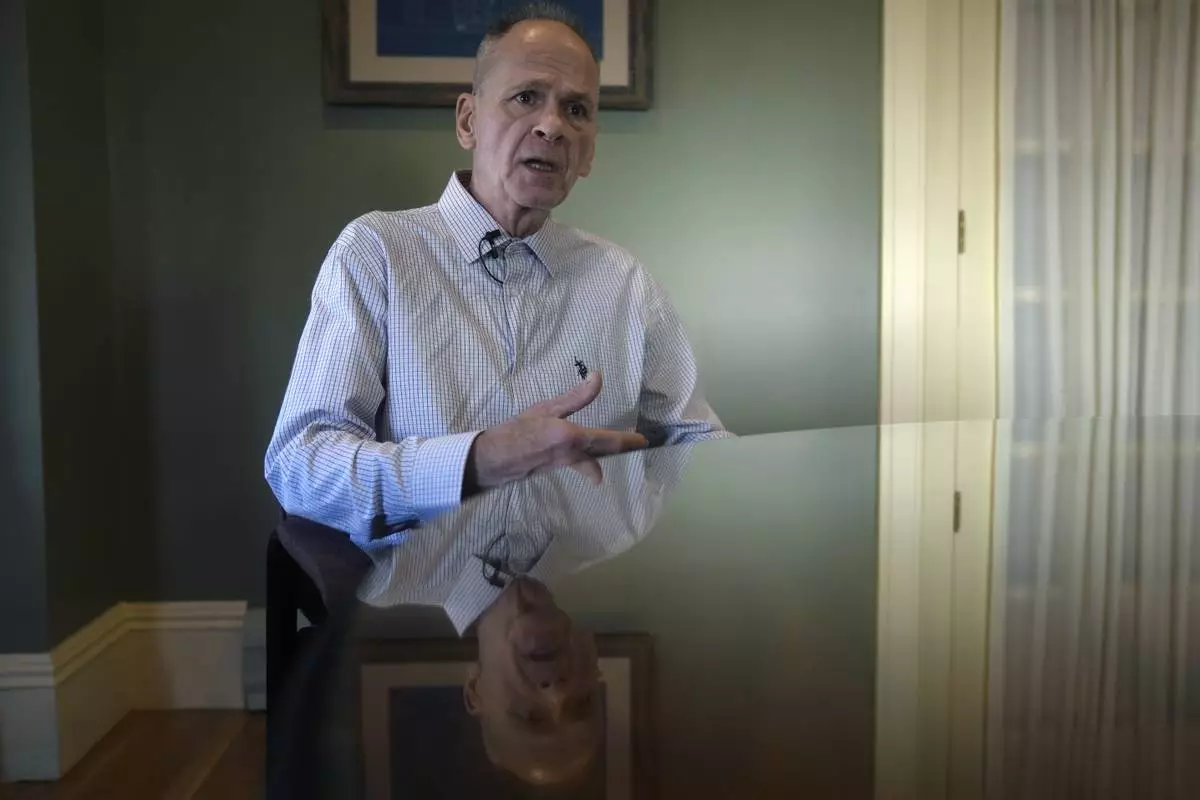

Michael Sullivan, 64, of Lowell, Mass., who was convicted of murder and armed robbery in 1987 and spend years in jail before being ruled innocent, speaks to a reporter from The Associated Press at his attorney's office, Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024, in Framingham, Mass. (AP Photo/Steven Senne)

Pigeons belonging to Michael Sullivan, 64, of Lowell, Mass., stand together in a cage Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024, in Billerica, Mass. (AP Photo/Steven Senne)

Michael Sullivan, 64, of Lowell, Mass., who was convicted of murder and armed robbery in 1987 and spend years in jail before being ruled innocent, speaks to a reporter from The Associated Press at his attorney's office, Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024, in Framingham, Mass. (AP Photo/Steven Senne)

Michael Sullivan, 64, of Lowell, Mass., who was convicted of murder and armed robbery in 1987 and spend years in jail before being ruled innocent, stands near his pigeons at the home of his sister, Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024, in Billerica, Mass. (AP Photo/Steven Senne)