MILWAUKEE (AP) — The Aurora Health Care Mobile Medical Clinic team waited patiently at a table in the main hallway of the Milwaukee Public Library’s sprawling downtown branch, a blood pressure cuff and mental health questionnaire at the ready as they called out to patrons who paused: “Do you have any questions about your health?”

On this Tuesday afternoon, one man did. His joints were bothering him, he told Carolyn McCarthy, the team’s nurse practitioner. And he knew his bones need calcium to stay strong, so he stopped taking his blood pressure medication, a calcium channel blocker.

McCarthy talked with him at length in simple and specific terms about how the medication worked on his cells, why it was important to take and how it doesn’t affect calcium storage in his bones.

“Hopefully, he walked away a little bit more informed,” McCarthy said.

The mobile clinic is one of several health programs offered by libraries around across the U.S. — from tiny rural town libraries to large urban systems. They offer fitness classes, food pantries, cooking classes, conversations about loneliness and mental health, and even blood pressure monitors that can be checked out just like books.

The public health programs leverage libraries' reputation as sources of reliable information and their ability to reach people beyond formal health care settings. No money, insurance, language skills or ID required, no limits on age. All are welcome.

Libraries are “the last true public institution,” said Jaime Placht, a health and well-being specialist at the Kansas City Public Library system in Kansas City, Missouri. The system has a full-time social work team. “The library is a public health space.”

The Kansas City Public Library, along with Milwaukee and several others, is part of the American Heart Association's Libraries with Heart program. Several Kansas City branches have blood pressure stations — which Placht said have been used 13,000 times — as well as a take-home blood pressure kits that have been checked out nearly 100 times. The program started there about a year ago.

“We have patrons that say, ‘Because I used the blood pressure monitor at the library, I went and saw my physician for the first time in a long time,’” Placht said.

There is no local public health office in Jarrell, Texas, a small town between Austin and Waco. But there is a nonprofit library that can connect patrons to mental health help. It's one of nine rural libraries in central Texas that receives funding from the St. David’s Foundation, the philanthropic arm of one of the state’s largest health systems.

Jarrell Community Library and Resource Center is a place for brave conversations. When a senior card game group turned to a discussion of the best crematorium in town, the library brought in local experts to teach about end-of-life planning, library director Susan Gregurek said. Last year, seven women came to the library for information on how to file restraining orders against their husbands.

“This is mental health, but it’s obviously larger than mental health," Gregurek said.

The public library in Smithville, Texas, which also gets money from the Libraries for Health program, stocks boxes of surplus food from area farmers and built out programs that help teens, older adults and parents address isolation. The library’s peer support specialist has gone from working with four to five people a month to nearly 60 in the community southeast of Austin.

St. David's Foundation has invested more than $3 million in the program over three years, which Smithville library director Judy Bergeron said is key when she hears comments like, “Why are we funding the library so much? Nobody reads anymore.”

A year and a half into being in Milwaukee's libraries, mobile health clinic reaches eight patrons on average per visit. They've had some people come back to say they went to the hospital and got a life-saving treatment, McCarthy said. They’ve also had patients who did not seek help and later died.

“What we do is a Band-Aid on a broken (health care) system,” McCarthy said of the clinic.

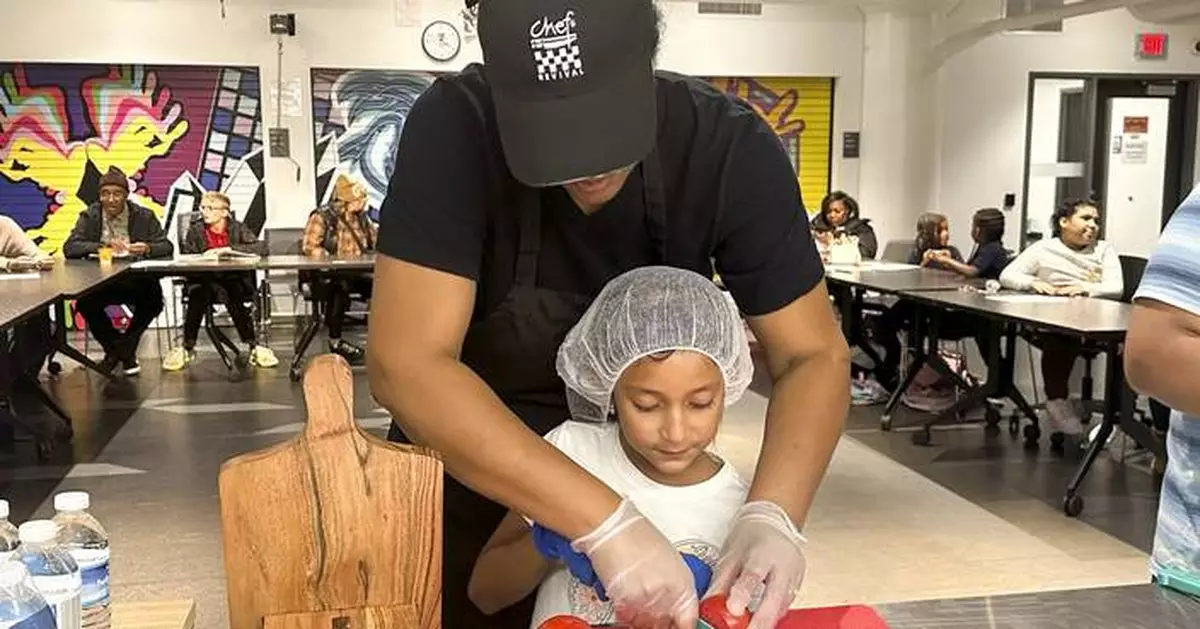

Another library effort in Milwaukee teaches kids about healthy nutrition habits at the Mitchell Street branch — a weekly after-school program run by chef Sharrie Agee since 2022.

“Certain areas of Milwaukee don’t have the same opportunities to (access) healthy ingredients, healthy sources of food, the knowledge behind how to use those ingredients,” said Agee, whose class learns how to make snacks from different continents.

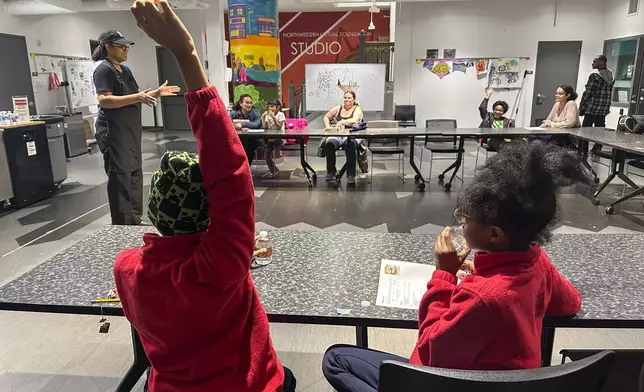

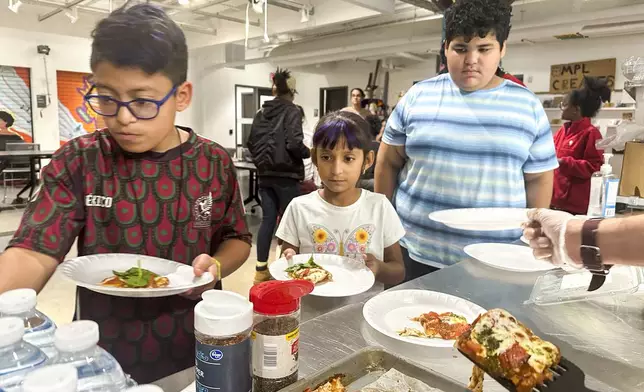

Four junior chefs helped her cut cheese and tomatoes for a pizza this month while she quizzed the rest of the attendees: What country is pizza from? What ingredients are listed on the recipe?

Ruby Herrera, 40, brought her children to help them learn to cook something healthy and try different foods. Her older kids cook everything in the air fryer.

Yareni Orduna-Herrera, 7, ran over to her mom, smiling, her task of slicing tomatoes complete.

She said she'll try the recipe home again and also wants to learn to make rice and beans. But first, she needed to taste the pizza.

“The one that I made,” she said with pride.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Chef Sharrie Agee prepares food as part of the Milwaukee Public Library’s Snack Hack program for kids on Nov. 19, 2024, Milwaukee. (AP Photo/Devi Shastri)

A child raises his hand to answer a question asked by Chef Sharrie Agee at the Milwaukee Public Library’s Snack Hack program for kids on Nov. 19, 2024, Milwaukee. (AP Photo/Devi Shastri)

Attendees of the after school nutrition program, Milwaukee Public Library Snack Hack, line up to get a slice of pizza made from scratch, Nov. 19, 2024, in Milwaukee. (AP Photo/Devi Shastri)

A free blood pressure machine is used at the public library in Kansas City, Mo., on Nov. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Nick Ingram)

Attendees stretch during a fitness class at the public library in Kansas City, Mo., on Nov. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Nick Ingram)

Chef Sharrie Agee helps Yareni Orduna-Herrera slice tomatoes for a margherita pizza as part of the Milwaukee Public Library Snack Hack, an after school nutrition program that teaches kids how to make healthy meals at home, Nov. 19, 2024, in Milwaukee. (AP Photo/Devi Shastri)