REYKJAVIK, Iceland (AP) — Icelanders will elect a new parliament Saturday after disagreements over immigration, energy policy and the economy forced Prime Minister Bjarni Benediktsson to pull the plug on his coalition government and call early elections.

This is Iceland’s sixth general election since the 2008 financial crisis devastated the economy of the North Atlantic island nation and ushered in a new era of political instability.

Click to Gallery

A view of Tjörnin, the city pond completely frozen, with the city hall at left, and downtown Reykjavik in the background, Friday, Nov. 29, 2024. (AP Photo Marco Di Marco)

A view of Hallgrímskirkja, the main church of Reykjavík and the most famous landmark of the capital of Iceland, in Reykjavik, Iceland, Friday, Nov. 29, 2024. (AP Photo Marco Di Marco)

Cars drive past a bilboard of the Left Green Party (Vinstri græn) reading "Let's stay on the left side, in Reykjavik, Iceland, Friday, Nov. 29, 2024. (AP Photo Marco Di Marco)

A bilboard of the People's Party (Flokkur Fólksins) reading "It's your turn", in Reykjavik, Iceland, Friday, Nov. 29, 2024. (AP Photo Marco Di Marco)

A bilboard of the Progressive Party (Framsóknarflokkurinn) reading "Lower interest rates - More Progress", is backdropped by Mt. Esja covered with fresh snow in Reykjavik, Iceland, Friday, Nov. 29, 2024. (AP Photo Marco Di Marco)

A bilboard of the Independente Party (Sjálfstæðisflokkurinn) with the photo of the current Prime Minister Bjarni Benediktsson reading "Success! Do not turn left", in Reykjavik, Iceland, Friday, Nov. 29, 2024. (AP Photo Marco Di Marco)

A Bilboard of the Democratic Party (Lýðræðisflokkurinn) reading "Let's limit the interest rate by law to a maximum of 4%" is backdropped by Mt. Esja covered with fresh snow, in Reykjavik, Iceland, Friday, Nov. 29, 2024. (AP Photo Marco Di Marco)

Opinion polls suggest the country may be in for another upheaval, with support for the three governing parties plunging. Benediktsson, who was named prime minister in April following the resignation of his predecessor, struggled to hold together the unlikely coalition of his conservative Independence Party with the centrist Progressive Party and the Left-Green Movement.

Iceland, a nation of about 400,000 people, is proud of its democratic traditions, describing itself as arguably the world’s oldest parliamentary democracy. The island’s parliament, the Althingi, was founded in 930 by the Norsemen who settled the country.

Here’s what to look for in the contest.

Voters will choose 63 members of the Althingi in an election that will allocate seats both by regional constituencies and proportional representation. Parties need at least 5% of the vote to win seats in parliament. Eight parties were represented in the outgoing parliament, and 10 parties are contesting this election.

Turnout is traditionally high by international standards, with 80% of registered voters casting ballots in the 2021 parliamentary election.

A windswept island near the Arctic Circle, Iceland normally holds elections during the warmer months of the year. But on Oct. 13 Benediktsson decided his coalition couldn’t last any longer, and he asked President Halla Tómasdóttir to dissolve the Althingi.

“The weakness of this society is that we have no very strong party and we have no very strong leader of any party,’’ said Vilhjálmur Bjarnson, a former member of parliament. “We have no charming person with a vision … That is very difficult for us.”

The splintering of Iceland's political landscape came after the 2008 financial crisis, which prompted years of economic upheaval after its debt-swollen banks collapsed.

The crisis led to anger and distrust of the parties that had traditionally traded power back and forth, and prompted the creation of new parties ranging from the environment focused Left-Green Alliance to the Pirate Party, which advocates direct democracy and individual freedoms.

“This is one of the consequences of the economic crash,’’ said Eva H. Önnudóttir, a professor of political science at the University of Iceland. “It’s just the changed landscape. Parties, especially the old parties, have maybe kind of been hoping that we would go back to how things were before, but that’s not going to happen.”

Like many Western countries, Iceland has been buffeted by the rising cost of living and immigration pressures.

Inflation peaked at an annual rate of 10.2% in February 2023, fueled by the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. While inflation slowed to 5.1% in October, that is still high compared with neighboring countries. The U.S. inflation rate stood at 2.6% last month, while the European Union’s rate was 2.3%.

Iceland is also struggling to accommodate a rising number of asylum-seekers, creating tensions within the small, traditionally homogenous country. The number of immigrants seeking protection in Iceland jumped to more than 4,000 in each of the past three years, compared with a previous average of less than 1,000.

Repeated eruptions of a volcano in the southwestern part of the country have displaced thousands of people and strained public finances. One year after the first eruption forced the evacuation of the town of Grindavik, many residents still don’t have secure housing, leading to complaints that the government has been slow to respond.

But it also added to a shortage of affordable housing exacerbated by Iceland’s tourism boom. Young people are struggling to get a foot on the housing ladder at a time when short-term vacation rentals have reduced the housing stock available for locals, Önnudóttir said.

“The housing issue is becoming a big issue in Iceland,'' she said. ——

Kirka reported from London.

A view of Tjörnin, the city pond completely frozen, with the city hall at left, and downtown Reykjavik in the background, Friday, Nov. 29, 2024. (AP Photo Marco Di Marco)

A view of Hallgrímskirkja, the main church of Reykjavík and the most famous landmark of the capital of Iceland, in Reykjavik, Iceland, Friday, Nov. 29, 2024. (AP Photo Marco Di Marco)

Cars drive past a bilboard of the Left Green Party (Vinstri græn) reading "Let's stay on the left side, in Reykjavik, Iceland, Friday, Nov. 29, 2024. (AP Photo Marco Di Marco)

A bilboard of the People's Party (Flokkur Fólksins) reading "It's your turn", in Reykjavik, Iceland, Friday, Nov. 29, 2024. (AP Photo Marco Di Marco)

A bilboard of the Progressive Party (Framsóknarflokkurinn) reading "Lower interest rates - More Progress", is backdropped by Mt. Esja covered with fresh snow in Reykjavik, Iceland, Friday, Nov. 29, 2024. (AP Photo Marco Di Marco)

A bilboard of the Independente Party (Sjálfstæðisflokkurinn) with the photo of the current Prime Minister Bjarni Benediktsson reading "Success! Do not turn left", in Reykjavik, Iceland, Friday, Nov. 29, 2024. (AP Photo Marco Di Marco)

A Bilboard of the Democratic Party (Lýðræðisflokkurinn) reading "Let's limit the interest rate by law to a maximum of 4%" is backdropped by Mt. Esja covered with fresh snow, in Reykjavik, Iceland, Friday, Nov. 29, 2024. (AP Photo Marco Di Marco)

BUSAN, South Korea (AP) — The world’s nations will wrap up negotiating a treaty this weekend to address the global plastic pollution crisis.

Their meeting concludes Sunday or early Monday in Busan, South Korea, where many environmental organizations have also flocked to push for a treaty to address the volume of production and toxic chemicals used in plastic products.

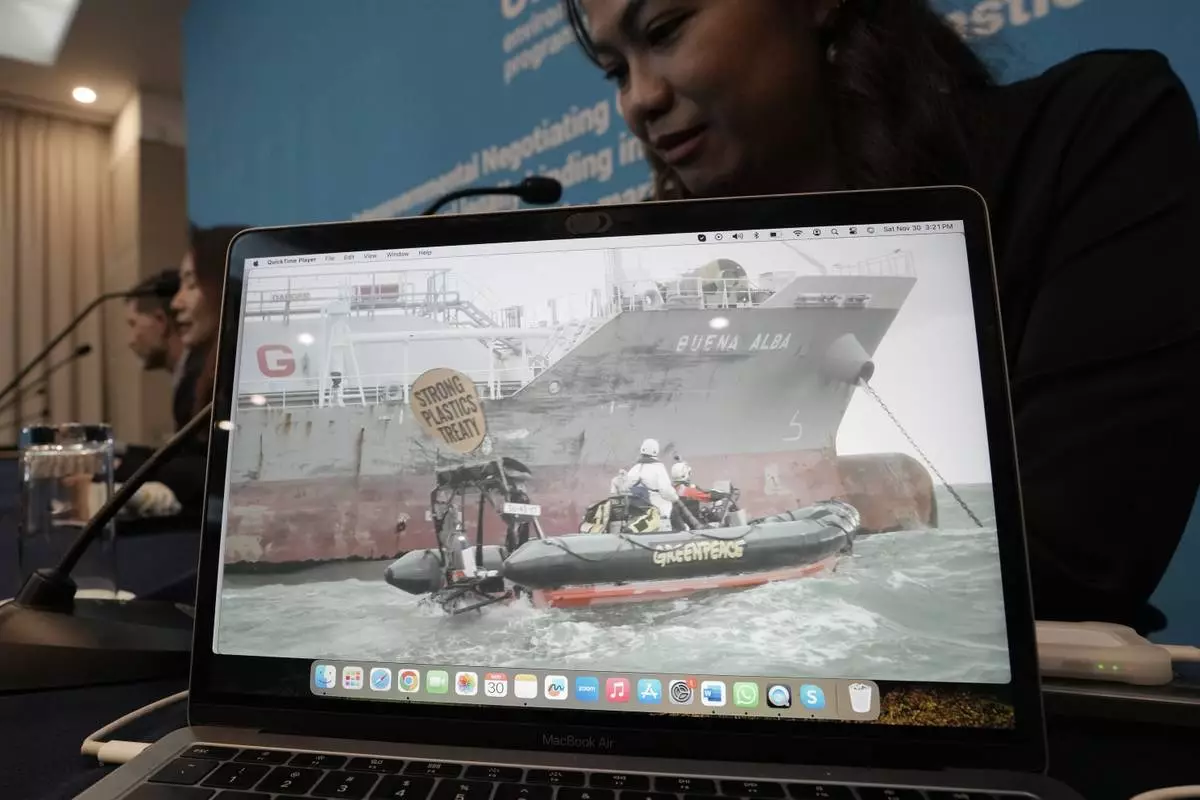

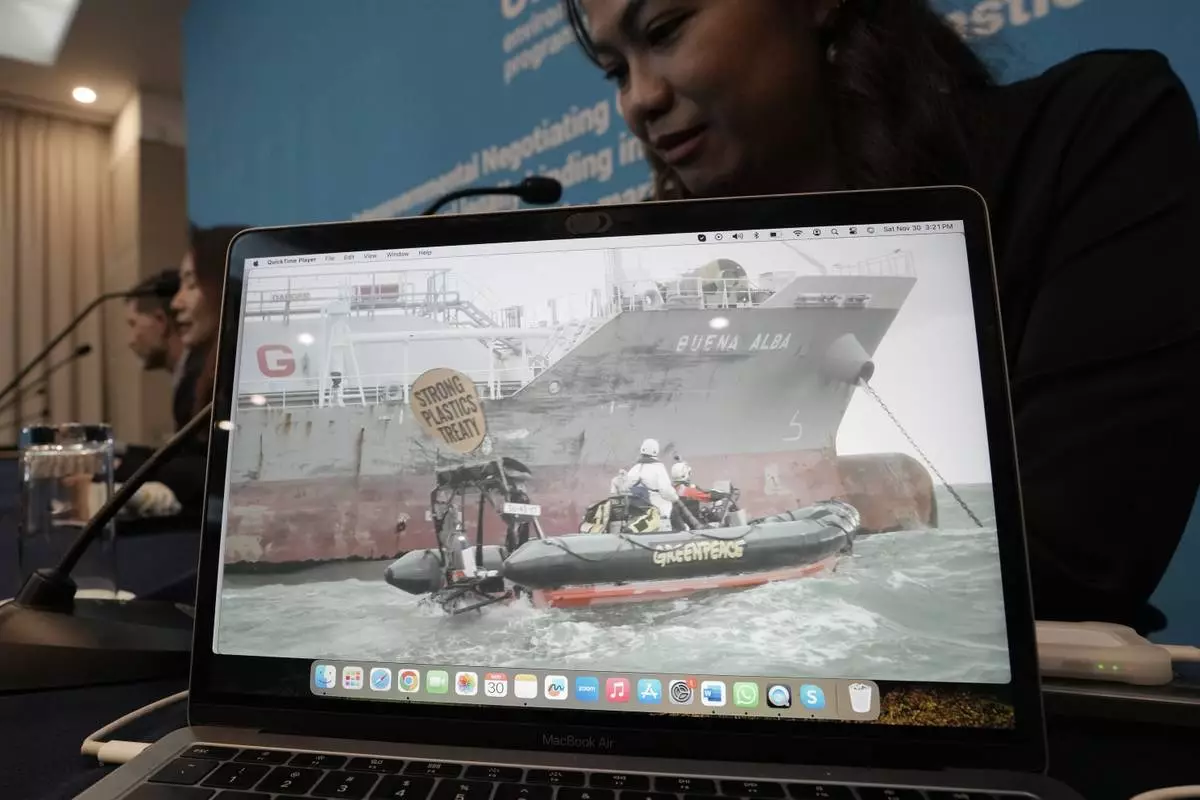

Greenpeace said it escalated its pressure Saturday by sending four international activists to Daesan, South Korea, who boarded a tanker headed into port to load chemicals used to make plastics.

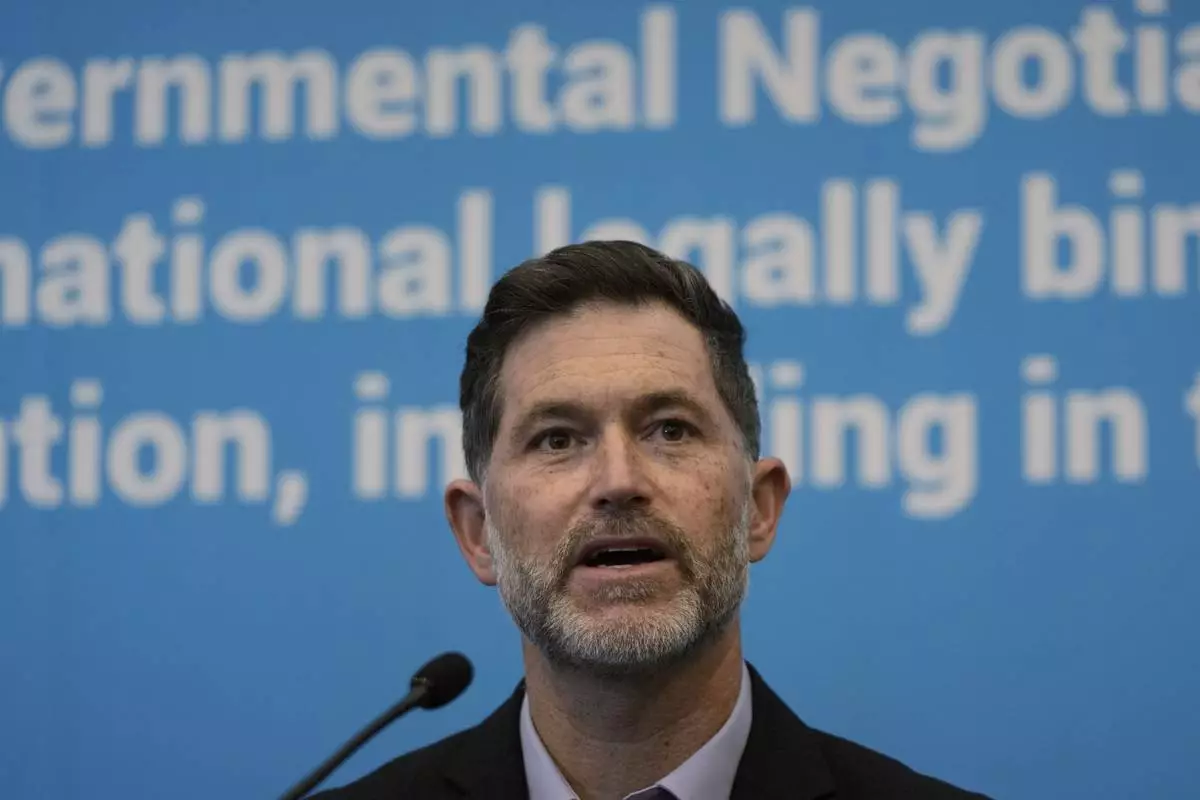

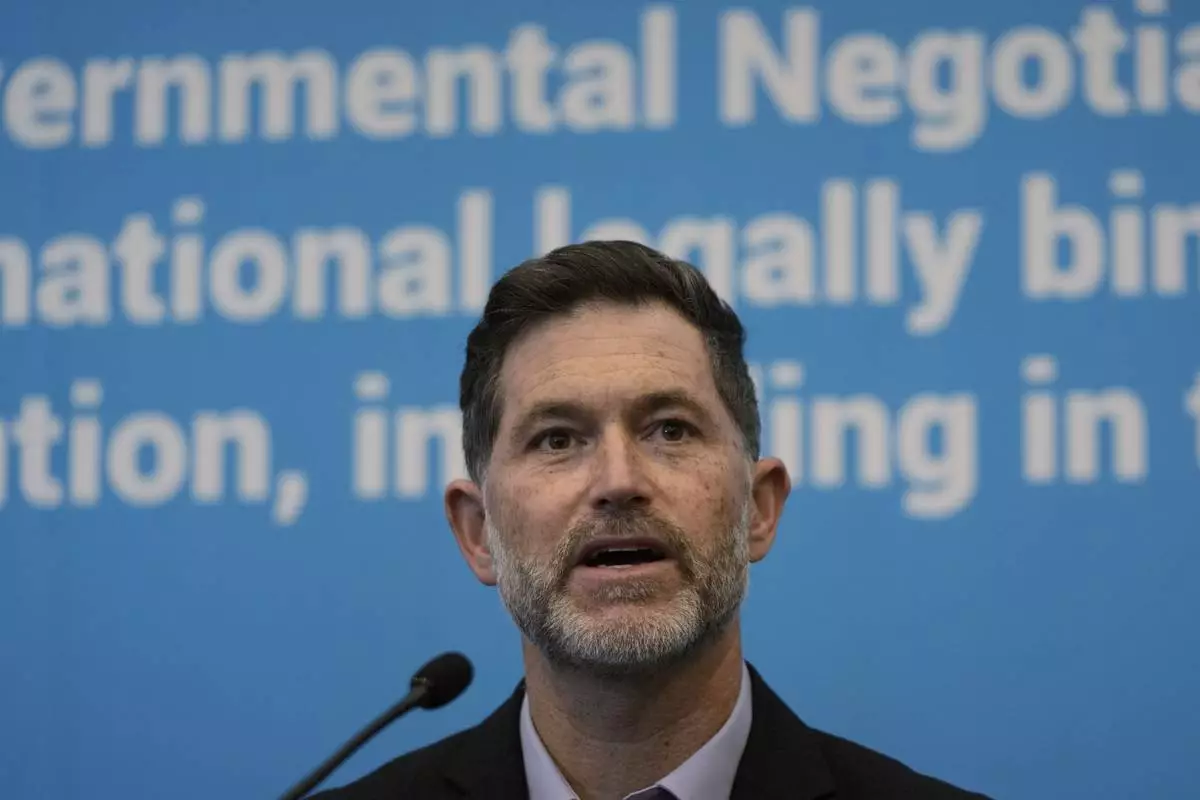

Graham Forbes, who leads the Greenpeace delegation in Busan, said the action is meant to remind world leaders they have a clear choice: Deliver a treaty that protects people and the planet, or side with industry and sacrifice the health of every living person and future generations.

Here’s what to know about plastics:

The use of plastics has quadrupled over the past 30 years. Plastic is ubiquitous. And every day, the equivalent of 2,000 garbage trucks full of plastic are dumped into the world’s oceans, rivers and lakes, the UN said. Most nations agreed to make the first global, legally binding plastic pollution accord, including in the oceans, by the end of 2024.

The production and use of plastics globally is set to reach 736 million tons by 2040, according to the intergovernmental Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Panama is leading an effort to address the exponential growth of plastic production as part of the treaty, supported by more than 100 countries. There’s just too much plastic, said Juan Carlos Monterrey, head of Panama’s delegation.

“If we don’t have production in this treaty, it is not only going to be horribly sad, but the treaty may as well be called the greenwashing recycling treaty, not the plastics treaty,” he said in an interview. “Because the problem is not going to be fixed.”

China was by far the biggest exporter of plastic products in 2023, followed by Germany and the U.S., according to the Plastics Industry Association.

Together, the three nations account for 33% of the total global plastics trade, the association said.

The United States supports having an article in the treaty that addresses supply, or plastic production, a senior member of the U.S. delegation told The Associated Press Saturday.

Less than 10% of plastics are recycled. Most of the world’s plastic goes to landfills, pollutes the environment, or is burned.

Sarah Dunlop, head of plastics and human health at the Minderoo Foundation, said chemicals are leaching out of plastics and “making us sick.”

The International Indigenous Peoples Forum on Plastics held an event about the impact of plastics Saturday on the sidelines of the talks. They want the treaty to fully recognize their rights, and the universal human right to a healthy, clean, safe and sustainable environment. Juan Mancias of the Carrizo/Comecrudo Nation in Texas spoke about feeling a spiritual connection to the land.

“Five hundred years ago, we had clean water, clean air and there was no plastics,” he said. “What happened?”

About 40% of all plastics are used in packaging, according to the UN. This includes single-use plastic food and beverage containers — water bottles, takeout containers, coffee lids, straws and shopping bags — that often end up polluting the environment.

U.N. Environment Program Executive Director Inger Andersen told negotiators in Busan the treaty must tackle this problem.

“Are there specific plastic items that we can live without, those that so often leak into the environment? Are there alternatives to these items? This is an issue we must agree on,” she said.

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

People pass by an electric display board calling for a reduction in plastic production near the venue for the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution in Busan, South Korea, Saturday, Nov. 30, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

A display board shows a call for a reduction in plastic production during the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution, at a taxi station in Busan, South Korea, Saturday, Nov. 30, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

A screen shows Greenpeace activists boarding a tanker on Saturday, to demand that nations agree to reduce plastic production, during a press conference of Greenpeace at the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution in Busan, South Korea, Saturday, Nov. 30, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

Graham Forbes, Greenpeace Head of Delegation to the Global Plastics Treaty Negotiations, speaks during a press conference at the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution in Busan, South Korea, Saturday, Nov. 30, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

Juan Benito Marcias, a member of The International Indigenous Peoples' Forum on Plastic, speaks during a press conference at the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution in Busan, South Korea, Saturday, Nov. 30 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

Juan Carlos Monterrey, right, head of Panama's delegation, speaks before a press conference of members of The International Indigenous Peoples' Forum on Plastics at the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution in Busan, South Korea, Saturday, Nov. 30, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

Members of The International Indigenous Peoples' Forum on Plastics attend a press conference at the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution in Busan, South Korea, Saturday, Nov. 30, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)