CHARLOTTE, N.C. (AP) — Baker Mayfield is hoping the NCAA doesn't outlaw flag planting.

Mayfield, who gained notoriety when he ran onto the field and planted an Oklahoma flag at midfield of Ohio State's stadium following a win by the Sooners in 2017, said the altercations Saturday that followed similar flag-planting incidents across the country are just part of college football's rivalries.

“I’ll say this: OU-Texas does it every time they play," Mayfield said after leading the Tampa Bay Buccaneers to a 26-23 overtime win over the Carolina Panthers on Sunday. “It’s not anything special. You take your ‘L’ and you move on. I’ll leave it at that.”

On Sunday, the Big Ten Conference fined Michigan and Ohio State $100,000 each for violating the conference’s sportsmanship policy for the on-field melee at the end of the Wolverines’ win in Columbus, Ohio.

Wolverine players attempted to the plant the Michigan flag on the OSU logo at midfield and were quickly confronted by Buckeyes players.

A fight broke out between the teams. Ohio State defensive end Jack Sawyer grabbed the top of the Wolverines’ flag and ripped it off the pole, and players were shoving and punching each other.

Police used pepper spray to break up the altercation. A police union official said one officer suffered a head injury when he was “knocked down and trampled while trying to separate players fighting."

The officer was treated at a hospital and released.

Similar scenes played out in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, after at least one North Carolina State player tried to plant a Wolfpack flag on UNC’s field following a 35-30 win. And there was a dust-up in Tallahassee, Florida, after Gators edge rusher George Gumbs Jr. planted a flag on Florida State’s logo after a 31-11 win.

When asked if the NCAA should ban flag planting, Mayfield responded, “ College football’s meant to have rivalries. It’s like the Big 12 banning the ‘Horns down’ signal."

He added: “Let the boys play.”

AP NFL: https://apnews.com/hub/NFL

Tampa Bay Buccaneers quarterback Baker Mayfield against the Carolina Panthers during the first half of an NFL football game, Sunday, Dec. 1, 2024, in Charlotte, N.C. (AP Photo/Rusty Jones)

Florida State and Florida players scuffle at midfield after an NCAA college football game Saturday, Nov. 30, 2024, in Tallahassee, Fla. (AP Photo/Colin Hackley)

Florida State and Florida players scuffle at midfield after an NCAA college football game Saturday, Nov. 30, 2024, in Tallahassee, Fla. (AP Photo/Colin Hackley)

BUSAN, South Korea (AP) — Negotiators working on a treaty to address the global crisis of plastic pollution for a week in South Korea won’t reach an agreement and plan to resume the talks next year.

They are at an impasse over whether the treaty should reduce the total plastic on Earth and put global, legally binding controls on toxic chemicals used to make plastics.

The negotiations in Busan, South Korea, were supposed to be the fifth and final round to produce the first legally binding treaty on plastics pollution, including in the oceans, by the end of 2024. But with time running out early Monday, negotiators agreed to resume the talks next year. They don’t yet have firm plans.

More than 100 countries want the treaty to limit production as well as tackle cleanup and recycling, and many have said that is essential to address chemicals of concern. But for some plastic-producing and oil and gas countries, that crosses a red line.

For any proposal to make it into the treaty, every nation must agree to it. Some countries sought to change the process so decisions could be made with a vote if consensus couldn’t be reached and the process was paralyzed. India, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Kuwait and others opposed changing it, arguing consensus is vital to an inclusive, effective treaty.

On Sunday, the last scheduled day of talks, the treaty draft still had multiple options for several key sections. Some delegates and environmental organizations said it had become too watered down, including negotiators from Africa who said they would rather leave Busan without a treaty than with a weak one.

Every year, the world produces more than 400 million tons of new plastic. Plastic production could climb about 70% by 2040 without policy changes.

In Ghana, communities, bodies of water, drains and farmlands are choked with plastics, and dumping sites full of plastics are always on fire, said Sam Adu-Kumi, the country’s lead negotiator.

“We want a treaty that will be able to solve it,” he said in an interview. “Otherwise we will go without it and come and fight another time.”

At Sunday night’s meeting, Luis Vayas Valdivieso, the committee chair from Ecuador, said that while they made progress in Busan, their work is far from complete and they must be pragmatic. He said countries were the furthest apart on proposals about problematic plastics and chemicals of concern, plastic production and financing the treaty, as well as the treaty principles.

Valdivieso said the meeting should be suspended and resume at a later date. Many countries then reflected on what they must see in the treaty moving forward.

Rwanda’s lead negotiator, Juliet Kabera, said she spoke on behalf of 85 countries in insisting that the treaty be ambitious throughout, fit for purpose and not built to fail, for the benefit of current and future generations. She asked everyone who supported the statement to “stand up for ambition.” Country delegates and many in the audience stood, clapping.

Panama’s delegation, which led an effort to include plastic production in the treaty, said they would return stronger, louder and more determined.

Saudi Arabia’s negotiator said chemicals and plastic production are not within the scope of the treaty. Speaking on behalf of the Arab group, he said if the world addresses plastic pollution, there should be no problem producing plastic. Kuwait’s negotiator echoed that, saying the objective is to end plastic pollution, not plastic itself, and stretching the mandate beyond its original intent erodes trust and goodwill.

In March 2022, 175 nations agreed to make the first legally binding treaty on plastics pollution, including in the oceans, by the end of 2024. The resolution states that nations will develop an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution based on a comprehensive approach that addresses the full life cycle of plastic.

Stewart Harris, a spokesperson for the International Council of Chemical Associations, said it was an incredibly ambitious timeline. He said the ICCA is hopeful governments can reach an agreement with just a little more time.

Most of the negotiations in Busan took place behind closed doors. Environmental groups, indigenous leaders and others who traveled to Busan to help shape the treaty said it should’ve been transparent and they felt silenced.

“The voices of the impacted communities, science and health leaders are silent in the process, and to a large degree, this is why the negotiation process is failing,” said Bjorn Beeler, international coordinator for the International Pollutants Elimination Network. “Busan proved that the process is broken and just hobbling along.

South Korea’s foreign affairs minister Cho Tae-yul said that though they didn’t get a treaty in Busan as many had hoped, their efforts brought the world closer to a unified solution to ending global plastic pollution.

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Chair of the International Negotiating Committee Luis Vayas Valdivieso speaks during the start of a plenary of the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution in Busan, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

Chair of the International Negotiating Committee, Luis Vayas Valdivieso, on the screen, speaks during a plenary of the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution in Busan, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

Chair of the International Negotiating Committee Luis Vayas Valdivieso reacts during a plenary of the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution in Busan, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

Chair of the International Negotiating Committee, Luis Vayas Valdivieso, on the screen, speaks during a plenary of the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution in Busan, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

Delegates attend a plenary of the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution in Busan, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

Chair of the International Negotiating Committee, Luis Vayas Valdivieso, right, speaks with Inger Andersen, Executive Director of UNEP, before the start of a plenary of the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution in Busan, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

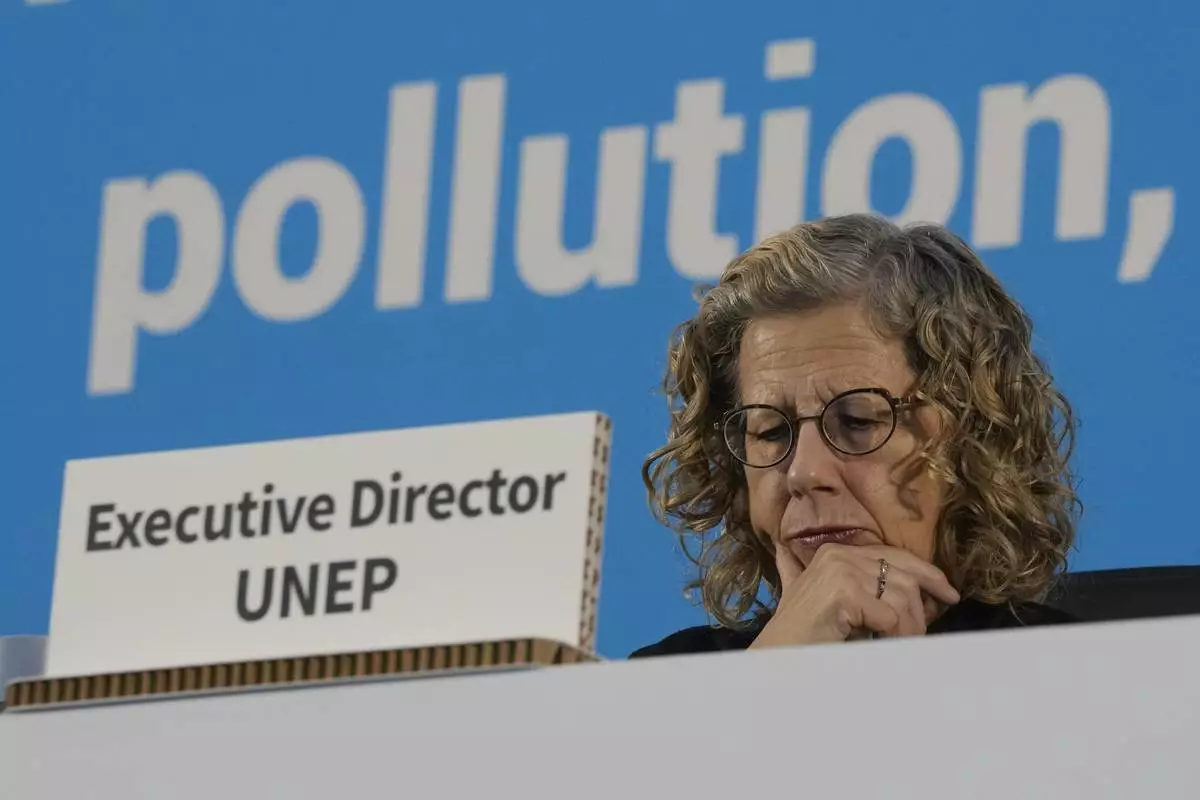

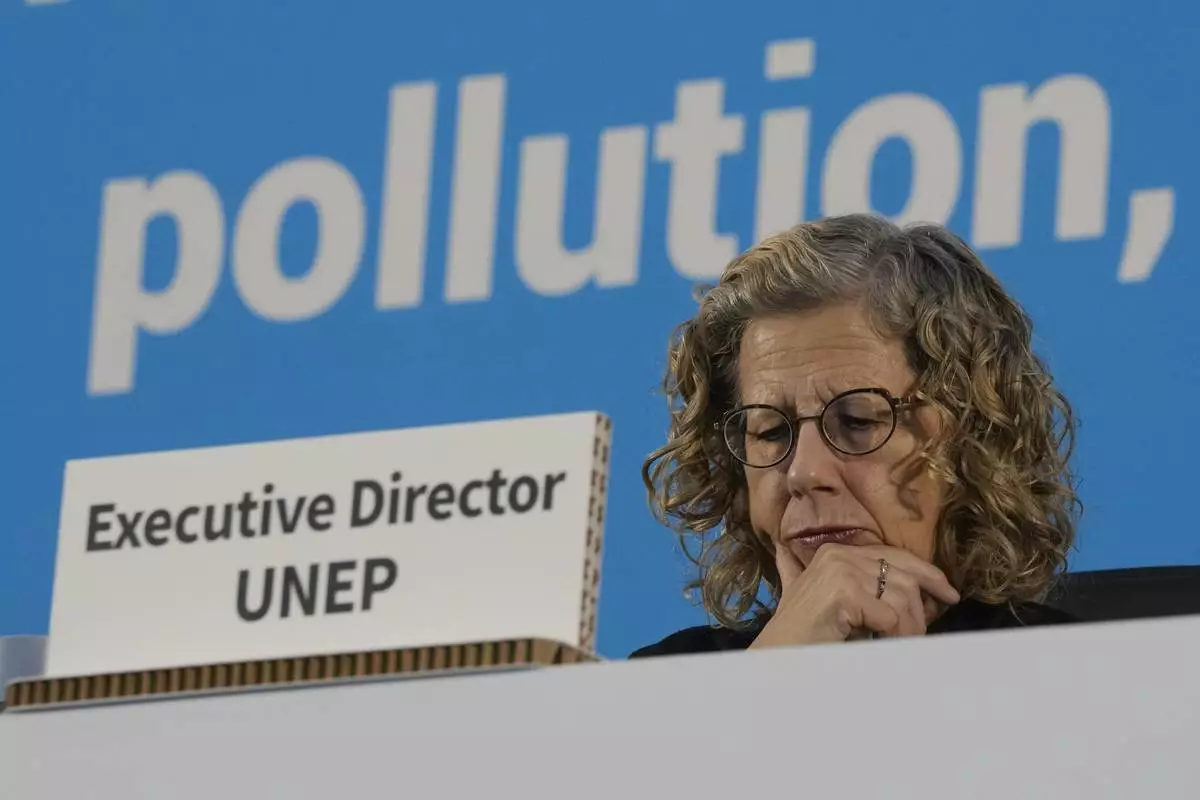

Inger Andersen, Executive Director of UNEP, gestures before the start of a plenary of the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution in Busan, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

People pass under an electric display board calling for a reduction in plastic production near the venue for the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution in Busan, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

South Korean Foreign Minister Cho Tae-yul speaks during a plenary of the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution in Busan, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

South Korean Foreign Minister Cho Tae-yul speaks during a plenary of the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution in Busan, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)