GENEVA (AP) — For the first time in Switzerland, a multinational company faces a criminal trial Monday on charges of bribing a foreign public official, with alleged payments totaling about $5 million, to win lucrative oil industry contracts in Angola.

Commodities trader Trafigura Group said Sunday it intended to defend itself against allegations that its former parent company did not have “reasonable and necessary” measures in place at the time to prevent unlawful payments to a former employee of Angola’s state oil company.

The case underscores renewed allegations of bribery in the commodities trading business, which have ensnared other big participants such as Swiss-based Glencore, and Gunvor, which is based in Cyprus but has major operations in Switzerland.

Last December, Swiss federal prosecutors announced that the company and three people — a former high-level Trafigura employee, a former official with Angolan state oil company Sonangol, and an ex-Trafigura employee acting as an intermediary — were indicted for alleged roles in bribery.

The former Angolan official has been charged with having accepted bribes of more than 4.3 million euros and $604,000 from Trafigura Group between April 2009 and October 2011.

Trafigura said it has invested “significant resources” in strengthening its compliance program over a number of years. The defendants are entitled to a presumption of innocence as the court case plays out in Switzerland.

The trial at the Swiss federal criminal court in the southern city of Bellinzona is set to run through Dec. 20 but could be extended into January.

Trafigura, with headquarters in Singapore, operates in sectors like oil and petroleum, metals and mining, and gas and power, and has more than 12,000 employees around the world.

FILE - Exterior view of The Federal Criminal Court in Bellinzona, Switzerland, Monday, March 9, 2020. (Samuel Golay/Keystone via AP, File)

THE HAGUE, Netherlands (AP) — The top United Nations court took up the largest case in its history on Monday, when it opened two weeks of hearings into what countries worldwide are legally required to do to combat climate change and help vulnerable nations fight its devastating impact.

After years of lobbying by island nations who fear they could simply disappear under rising sea waters, the U.N. General Assembly asked the International Court of Justice last year for an opinion on “the obligations of States in respect of climate change.”

Any decision by the court would be non-binding advice and couldn't directly force wealthy nations into action to help struggling countries. Yet it would be more than just a powerful symbol since it could be the basis for other legal actions, including domestic lawsuits.

“We want the court to confirm that the conduct that has wrecked the climate is unlawful,” Margaretha Wewerinke-Singh, who is leading the legal team for the Pacific island nation of Vanuatu, told The Associated Press.

In the decade up to 2023, sea levels have risen by a global average of around 4.3 centimeters (1.7 inches), with parts of the Pacific rising higher still. The world has also warmed 1.3 degrees Celsius (2.3 Fahrenheit) since preindustrial times because of the burning of fossil fuels.

Vanuatu is one of a group of small states pushing for international legal intervention in the climate crisis.

“We live on the front lines of climate change impact. We are witnesses to the destruction of our lands, our livelihoods, our culture and our human rights,” Vanuatu’s climate change envoy Ralph Regenvanu told reporters ahead of the hearing.

The Hague-based court will hear from 99 countries and more than a dozen intergovernmental organizations over two weeks. It’s the largest lineup in the institution’s nearly 80-year history.

Last month at the United Nations’ annual climate meeting, countries cobbled together an agreement on how rich countries can support poor countries in the face of climate disasters. Wealthy countries have agreed to pool together at least $300 billion a year by 2035 but the total is short of the $1.3 trillion that experts, and threatened nations, said is needed.

“For our generation and for the Pacific Islands, the climate crisis is an existential threat. It is a matter of survival, and the world’s biggest economies are not taking this crisis seriously. We need the ICJ to protect the rights of people at the front lines,” said Vishal Prasad, of Pacific Islands Students Fighting Climate Change.

Fifteen judges from around the world will seek to answer two questions: What are countries obliged to do under international law to protect the climate and environment from human-caused greenhouse gas emissions? And what are the legal consequences for governments where their acts, or lack of action, have significantly harmed the climate and environment?

The second question makes particular reference to “small island developing States” likely to be hardest hit by climate change and to “members of “the present and future generations affected by the adverse effects of climate change.”

The judges were even briefed on the science behind rising global temperatures by the U.N.’s climate change body, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, ahead of the hearings.

Activists put up a billboard outside the International Court of Justice, in The Hague, Netherlands, as it opens hearings into what countries worldwide are legally required to do to combat climate change and help vulnerable nations fight its devastating impact, Monday, Dec. 2, 2024. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

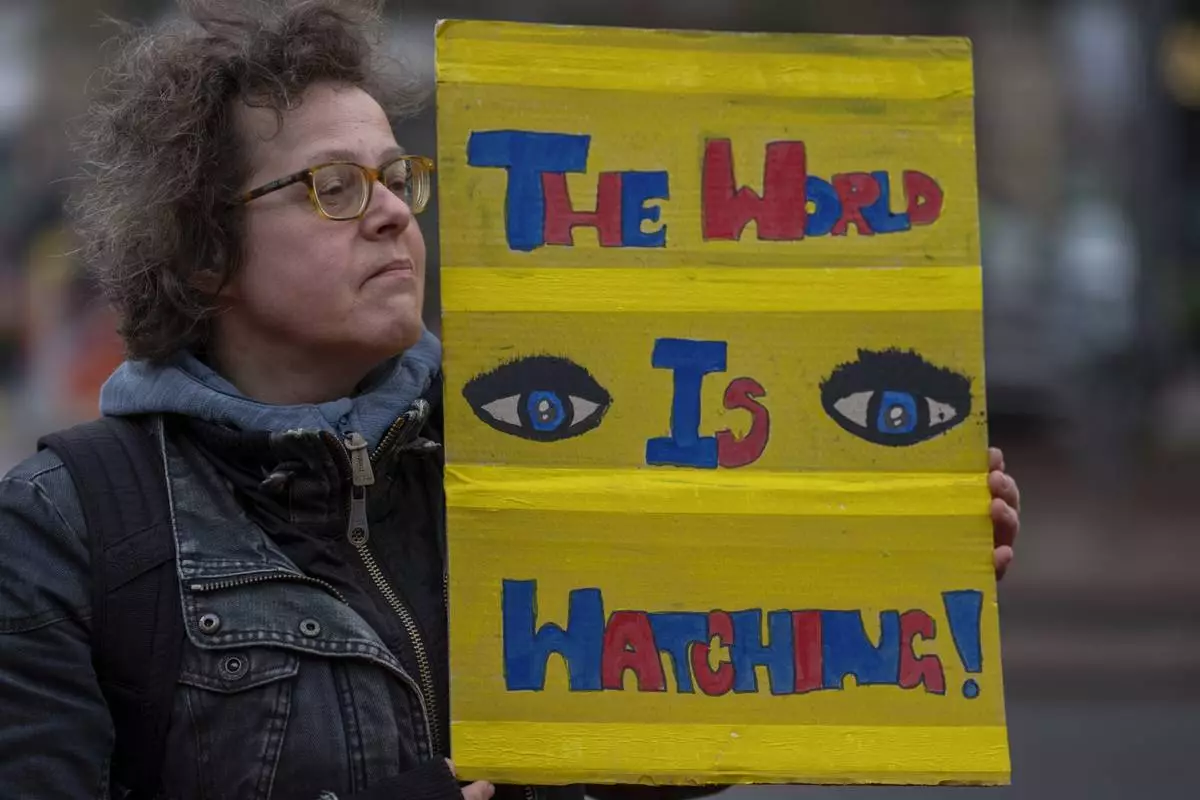

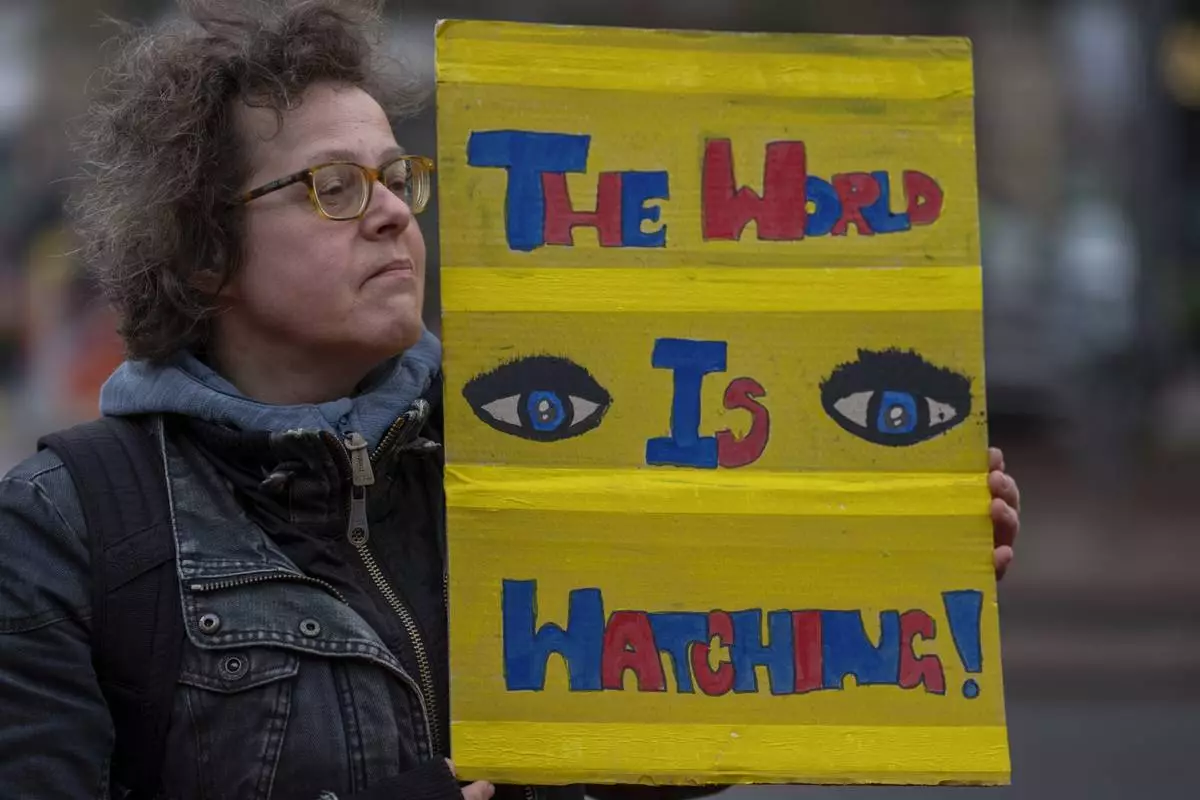

Activists protest outside the International Court of Justice, in The Hague, Netherlands, as it opens hearings into what countries worldwide are legally required to do to combat climate change and help vulnerable nations fight its devastating impact, Monday, Dec. 2, 2024. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Activists protest outside the International Court of Justice, in The Hague, Netherlands, as it opens hearings into what countries worldwide are legally required to do to combat climate change and help vulnerable nations fight its devastating impact, Monday, Dec. 2, 2024. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Activists protest outside the International Court of Justice, in The Hague, Netherlands, as it opens hearings into what countries worldwide are legally required to do to combat climate change and help vulnerable nations fight its devastating impact, Monday, Dec. 2, 2024. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Activists put up a billboard outside the International Court of Justice, in The Hague, Netherlands, as it opens hearings into what countries worldwide are legally required to do to combat climate change and help vulnerable nations fight its devastating impact, Monday, Dec. 2, 2024. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

FILE - The Peace Palace housing the World Court, or International Court of Justice, is reflected in a monument in The Hague, Netherlands, Wednesday, May 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong, File)