Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger has retired, the struggling chipmaker said Monday in a surprise announcement.

Two company executives, David Zinsner and Michelle Johnston Holthaus, will act as interim co-CEOs while the company searches for a replacement for Gelsinger, who also stepped down from the company's board.

The departure of Gelsinger, whose career spanned more than 40 years, underscores the turmoil at Intel. The company was once a dominant force in the semiconductor industry but has been eclipsed by rival Nvidia, which has cornered the market for chips that run artificial intelligence systems.

Gelsinger started at Intel in 1979 at Intel and was its first chief technology officer. He returned to Intel as chief executive in 2021.

Gelsinger said his exit was “bittersweet as this company has been my life for the bulk of my working career,” he said in a statement. “I can look back with pride at all that we have accomplished together. It has been a challenging year for all of us as we have made tough but necessary decisions to position Intel for the current market dynamics.”

Zinsner is executive vice president and chief financial officer at Intel. Holthaus was appointed to the newly created position of CEO of Intel Products, which includes the client computing, data center and AI groups.

Frank Yeary, independent chair of Intel's board, will become interim executive chair.

“Pat spent his formative years at Intel, then returned at a critical time for the company in 2021,” Yeary said in a statement. "As a leader, Pat helped launch and revitalize process manufacturing by investing in state-of-the-art semiconductor manufacturing, while working tirelessly to drive innovation throughout the company.”

Gelsinger's departure comes as Intel’s financial woes have been piling up. The company posted a $16.6 billion loss and halted its dividend in the most recent quarter, and its shares have fallen by about 60% since he took over as CEO. Gelsinger announced plans in August to slash 15% of its huge workforce — or about 15,000 jobs — as part of cost-cutting efforts to to save $10 billion in 2025.

Nvidia’s ascendance, meanwhile, was cemented earlier this month when it replaced Intel on the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

Unlike some of rivals, Intel manufactures chips in addition to designing them. Under Gelsinger, the company has been working to build up its foundry business making semiconductors in the U.S. designed by other firms, in a bid to compete with rivals such as market leader Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. or TSMC.

Intel has benefited from tens of billions of dollars that the administration has pledged to support construction of U.S. chip foundries and reduce reliance on Asian suppliers, which Washington sees as a security weakness.

After taking over as CEO, Gelsinger unveiled plans to build a $20 billion chipmaking facility in central Ohio, and poured billions more into expanding in Europe, where leaders were also worried about dependence on Asia.

The Biden administration had said it would give Intel up to $8.5 billion in federal funding for semiconductor plants around the country, but last week it trimmed that amount, according to three people familiar with the grant who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

Shares of the Santa Clara, California, company, rose 5.1% in morning trading.

AP Business Writer Kelvin Chan contributed to this report from London.

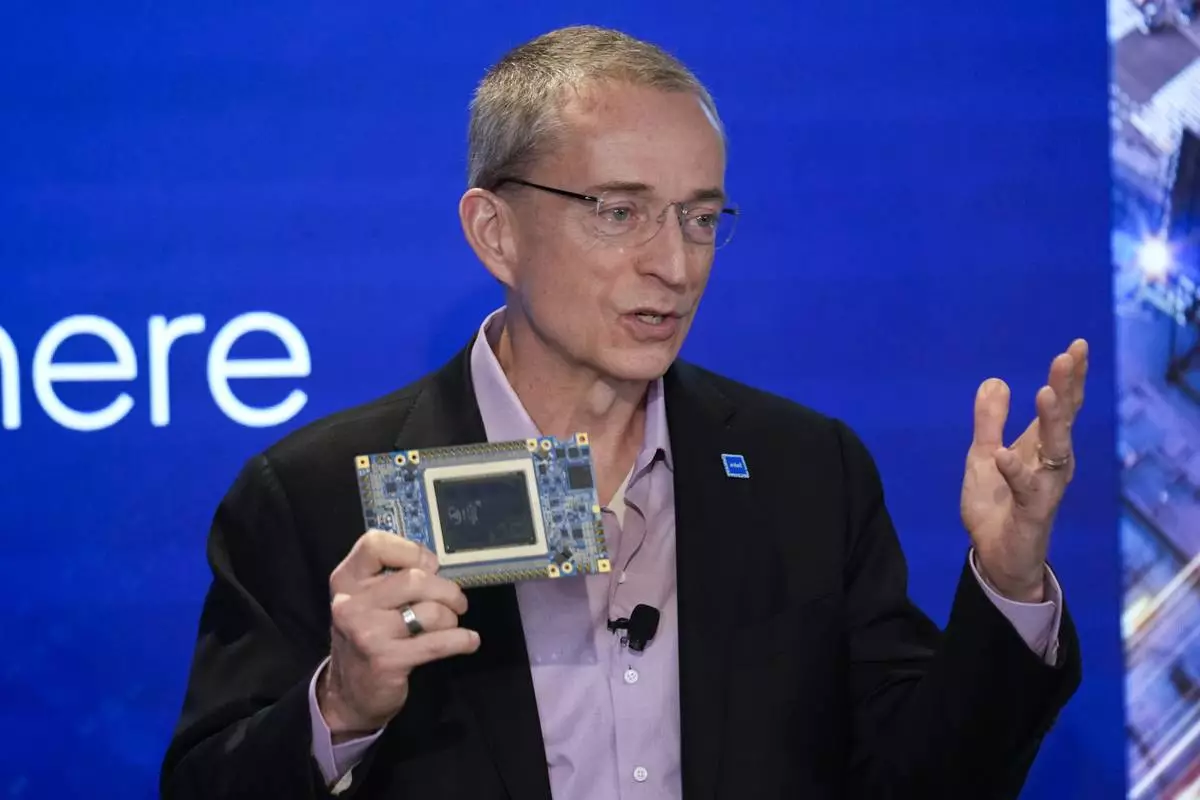

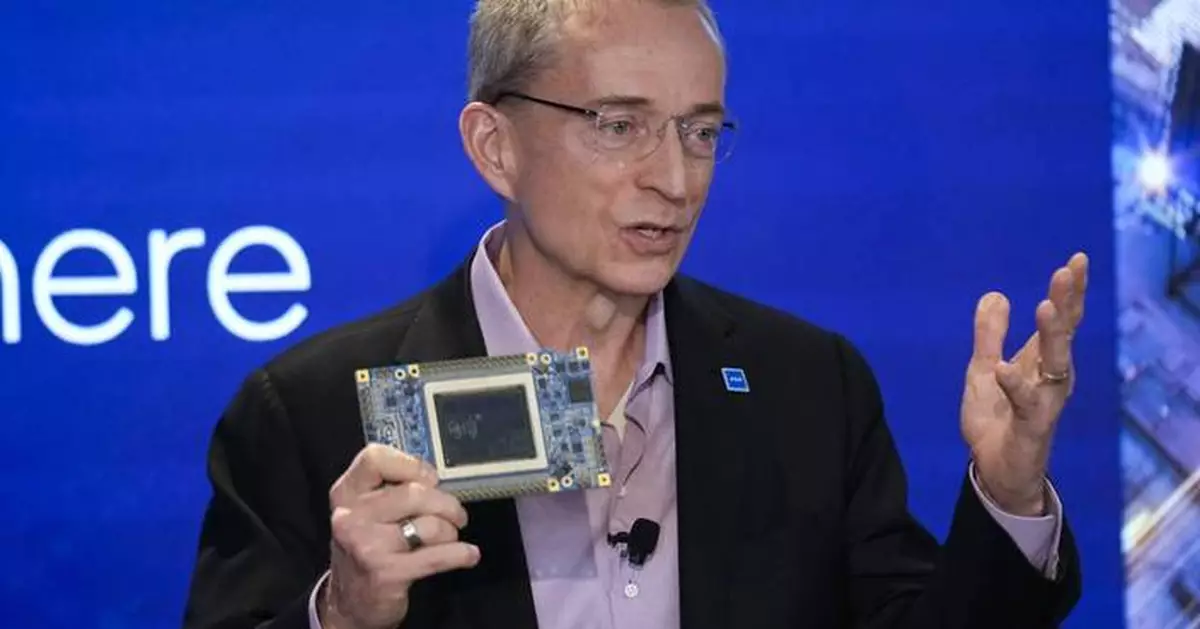

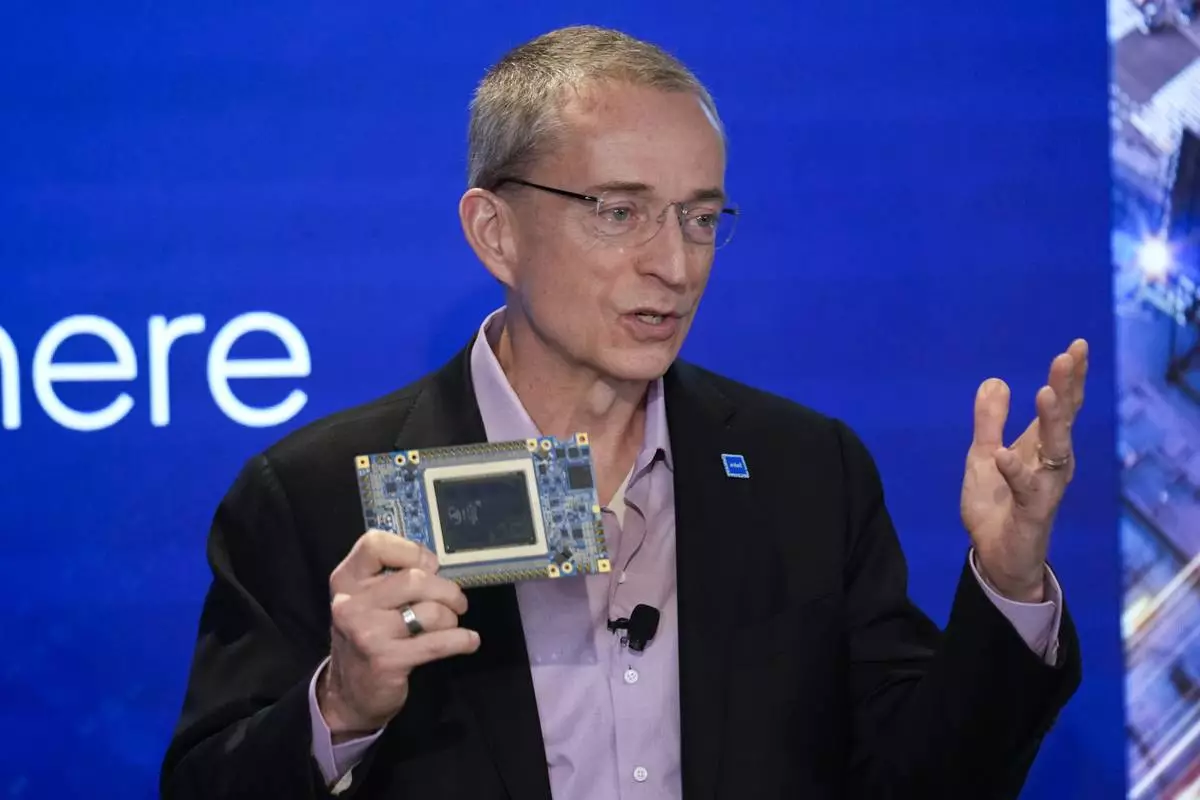

FILE - Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger speaks while holding a new chip, called Gaudi 3, during an event called AI Everywhere in New York, on Dec. 14, 2023. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig, File)

KANSAS CITY, Kan. (AP) — A white Kansas police detective accused of sexually assaulting Black women and girls and terrorizing those who tried to fight back is about to go on federal trial, part of a tangle of cases tied to decades of alleged abuse.

Prosecutors say female residents of poor neighborhoods in Kansas City, Kansas, feared that if they crossed paths with Roger Golubski, he'd demand sexual favors and threaten to harm or jail their relatives. He is charged with six felony counts of violating women's civil rights, and jury selection in his trial is set to begin Monday in a federal courthouse in Topeka.

The case has outraged the community and deepened the historical distrust of law enforcement. “Our emotions are everywhere," said Laquanda Jacobs, herself freed from prison through the work of the Midwest Innocence Project, as she waited in Kansas City, Kansas, to board a Topeka-bound bus with other advocates.

The prosecution follows earlier reports of similar abuse allegations across the country where hundreds of officers have lost their badges after allegations of sexual assaults.

Golubski, now 71, is accused of sexually assaulting one woman starting when she was barely a teenager and another after her sons were arrested. If a jury convicts him, he could die in prison.

About 50 people rallied outside the federal courthouse Monday morning in freezing temperatures to show their support for women who’ve said they were victimized by Golubski. They held signs that said, “Justice now!”

The trial is the latest in a string of lawsuits and criminal allegations that has led the county prosecutor’s office to begin a $1.7 million effort to reexamine cases Golubski worked on during his 35 years on the force. One double murder case Golubski investigated already has resulted in an exoneration, and an organization run by rapper Jay-Z is suing to obtain police records.

Golubski has pleaded not guilty, and his attorney has said that lawsuits over the allegations are an “inspiration for fabrication” by his accusers. But prosecutors said that, along with the two women whose accounts are the heart of the criminal case, seven others will testify that Golubski abused or harassed them.

“Every time I turn around, I’m looking," said Jermeka Hobbs, who has filed a separate lawsuit against Golubski and is not a witness in the trial. Her lawsuit says she was groomed to be one of “Golubski’s girls” and submitted to sexual advances fearing that he would bust her for drugs. “I’m thinking somebody is after me. I have no peace at all."

Fellow officers once revered Golubski for his ability to clear cases, and he rose to the rank of captain in Kansas City, Kansas, before retiring there in 2010 and then working on a suburban police force for six more years. His former partner served a stint as police chief.

Golubski now looks nothing like the influential officer he was. He is under house arrest and undergoing kidney dialysis treatments three times a week. That will limit his trial to Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays.

His attorney, Chris Joseph, said in a statement that some of the allegations against Golubski are 20 to 30 years old, adding, “In public filings, the prosecution has acknowledged that the verdict will turn entirely on the accusers’ credibility.”

But Jim McCloskey, founder of Centurion, a New Jersey nonprofit working to free innocent people, described Golubski in a court hearing as the “dirtiest cop I’ve ever encountered.”

Stories about Golubski remained just whispers in the neighborhoods near Kansas City's former cattle stockyards partly because of the extreme poverty of a place where some homes are boarded up. One neighborhood where Golubski worked is part of Kansas' second-poorest zip code.

Crime was abundant there, as were drug dealers and prostitutes, said Max Seifert, a former Kansas City, Kansas, police officer who graduated from the police academy with Golubski in 1975.

Seifert said police misconduct was tolerated in the department. He described how informants and Golubski’s ex-wife complained that Golubski was soliciting prostitutes. Golubski also was caught having sex with a woman in his office, he said.

“It’s kind of like a boys will be boys type thing,” said Seifert, who was forced into early retirement for refusing to conceal a motorist’s beating by a federal agent in 2003.

McCloskey said in an interview that Golubski had women "at his mercy.”

The inquiry into Golubski stems from the case of Lamonte McIntyre, who started writing to McCloskey’s nonprofit nearly two decades ago.

McIntyre was just 17 in 1994 when he was arrested and charged in connection with a double homicide, within hours of the crimes. He had an alibi; no physical evidence linked him to the killings; and an eyewitness believed the killer was an underling of a local drug dealer. Golubski and the dealer have since been charged in a separate federal case of running a violent sex trafficking operation.

The eyewitness only testified that McIntyre was the killer after Golubski and a now disbarred attorney threatened to take her children away, she alleged in a lawsuit.

McIntyre's mother said in a 2014 affidavit that she wonders whether her refusal to grant regular sexual favors to Golubski prompted him to retaliate against her son.

“She, like many people in the community, just viewed the police as all-powerful,” said Cheryl Pilate, an attorney who helped free McIntyre in 2017.

In 2022, the local government agreed to pay $12.5 million to McIntyre and his mother to settle a lawsuit after a deposition in which Golubski invoked his Fifth Amendment right to remain silent 555 times. The state also paid McIntyre $1.5 million.

“That was the thread that gave people some courage,” said Lindsay Runnels, who serves on the board of the Midwest Innocence Project.

Prosecutors say Golubski drove one of the women at the center of their criminal case to a cemetery and told her to find a spot to dig her own grave. He sexually assaulted her repeatedly, starting when she was just in middle school, leading her to suffer a miscarriage, court filings say.

Once, prosecutors say, he forced her to crawl on the ground with a dog leash around her neck in a remote spot near the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri Rivers. With no one around, he is accused of chanting, “Down by the river, said a hank a pank; Where they won’t find her until she stank."

Golubski introduced himself to Ophelia Williams, the other woman at the center of the case, by complimenting her legs and nightgown as police searched her home, prosecutors said.

Williams was terrified at the time because her 14-year-old twins had just been arrested in a double homicide. They ultimately admitted to the crime so police would free their 13-year-old brother, Williams said in a separate lawsuit.

Golubski began sexually assaulting her, alternating between threatening her and claiming he could help her sons, according to court records in the criminal case. The twins are now 40 and remain behind bars. The lawsuit she is part of questions their confessions.

The Associated Press generally does not name alleged victims of sexual assault, but Williams has told her story publicly.

Williams said in her lawsuit that she once mentioned making a complaint. She claims Golubski told her: “Report me to who, the police? I am the police."

Hanna reported from Topeka, Kansas.

FILE - Former Kansas City, Kansas, police detective Roger Golubski testifies, Oct. 24, 2022, at the Wyandotte County courthouse in Kansas City, Kan. (Emily Curiel/The Kansas City Star via AP)