WATONGA, Okla. (AP) — As the Watonga school system's Indian education director, Hollie Youngbear works to help Native American students succeed — a job that begins with getting them to school.

She makes sure students have clothes and school supplies. She connects them with federal and tribal resources. And when students don't show up to school, she and a colleague drive out and pick them up.

Nationwide, Native students miss school far more frequently than their peers, but not at Watonga High School. Youngbear and her colleagues work to connect with families in a way that acknowledges the history and needs of Native communities.

As she thumbed through binders in her office with records of every Native student in the school, Youngbear said a cycle of skipping school goes back to the abuse generations of Native students suffered at U.S. government boarding schools.

“If grandma didn’t go to school, and her grandma didn’t, and her mother didn’t, it can create a generational cycle,” said Youngbear, a member of the Arapaho tribe who taught the Cheyenne and Arapaho languages at the school for 25 years.

This story is part of a collaboration on chronic absenteeism among Native American students between The Associated Press and ICT, a news outlet that covers Indigenous issues.

Watonga schools collaborate with several Cheyenne and Arapaho programs that aim to lower Native student absenteeism. One helps students with school expenses and promotes conferences for tribal youth. Another holds monthly meetings with Watonga’s Native high school students during lunch hours to discourage underage drinking and drug use.

Oklahoma is home to 38 federally recognized tribes, many with their own education departments — and support from those tribes contributes to students' success. Of 34 states with data available for the 2022-2023 school year, Oklahoma was the only one where Native students missed school at lower rates than the state average, according to data collected by The Associated Press.

At Watonga High, fewer than 4% of Native students were chronically absent in 2022-23, in line with the school average, according to state data. Chronically absent students miss 10% or more of the school year, for both excused and unexcused reasons, which sets them behind in learning and heightens their chances of dropping out.

About 14% of students at the Watonga school on the Cheyenne-Arapaho reservation are Native American. With black-lettered Bible verses on the walls of its hallways, the high school resembles many others in rural Oklahoma. But student-made Native art decorates the classroom reserved for Eagle Academy, the school's alternative education program.

Students are assigned to the program when they struggle to keep up their grades or attendance, and most are Native American, classroom teacher Carrie Compton said. Students are rewarded for attendance with incentives like field trips.

Compton said she gets results. A Native boy who was absent 38 days one semester spent a short time in Eagle Academy during his second year of high school and went on to graduate last year, she said.

"He had perfect attendance for the first time ever, and it’s because he felt like he was getting something from school,” Compton said.

When students do not show up for school, Compton and Youngbear take turns visiting their homes.

“I can remember one year, I probably picked five kids up every morning because they didn’t have rides,” Compton said. “So at 7 o’clock in the morning, I just start my little route, and make my circle, and once they get into the habit of it, they would come to school.”

Around the country, Native students often have been enrolled in disproportionately large numbers in alternative education programs, which can worsen segregation. But the embrace of Native students by their Eagle Academy teacher sets a different tone from what some students experience elsewhere in the school.

Compton said a complaint she hears frequently from Native students in her room is, “The teachers just don’t like me.”

Bullying of Native students by non-Native students is also a problem, said Watonga senior Happy Belle Shortman, who is Kiowa, Cheyenne and Arapaho. She said Cheyenne students have been teased over aspects of their traditional ceremonies and powwow music.

“People here, they’re not very open, and they do have their opinions,” Shortman said. “People who are from a different culture, they don’t understand our culture and everything that we have to do, or that we have a different living than they do.”

Poverty might play a role in bullying as well, she said. “If you’re not in the latest trends, then you’re kind of just outcasted," she said.

Watonga staff credit the work building relationships with students for the low absenteeism rates, despite the challenges.

“Native students are never going to feel really welcomed unless the non-Native faculty go out of their way to make sure that those Native students feel welcomed," said Dallas Pettigrew, director of Oklahoma University’s Center for Tribal Social Work and a member of the Cherokee Nation.

Associated Press writer Sharon Lurye in New Orleans contributed to this report.

The Associated Press’ education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Trophies are displayed in a case at Watonga High School where about 14% of students at the school on the Cheyenne-Arapaho reservation are Native American, Wednesday, Oct. 2, 2024, in Watonga, Okla. (AP Photo/Nick Oxford)

Empty storefronts sit on Main Street on Wednesday, Oct. 2, 2024, in Watonga, Okla. (AP Photo/Nick Oxford)

A mural adorns the side of a downtown building on Wednesday, Oct. 2, 2024, in Watonga, Okla. (AP Photo/Nick Oxford)

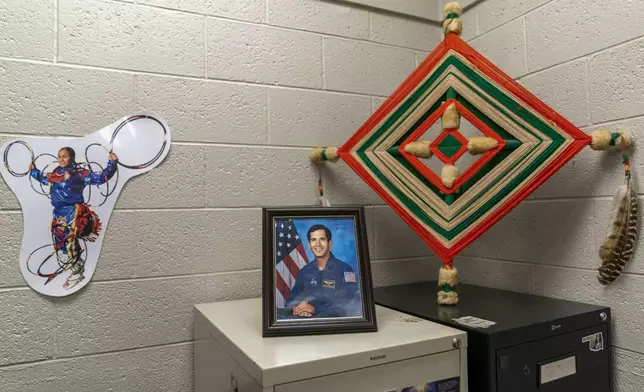

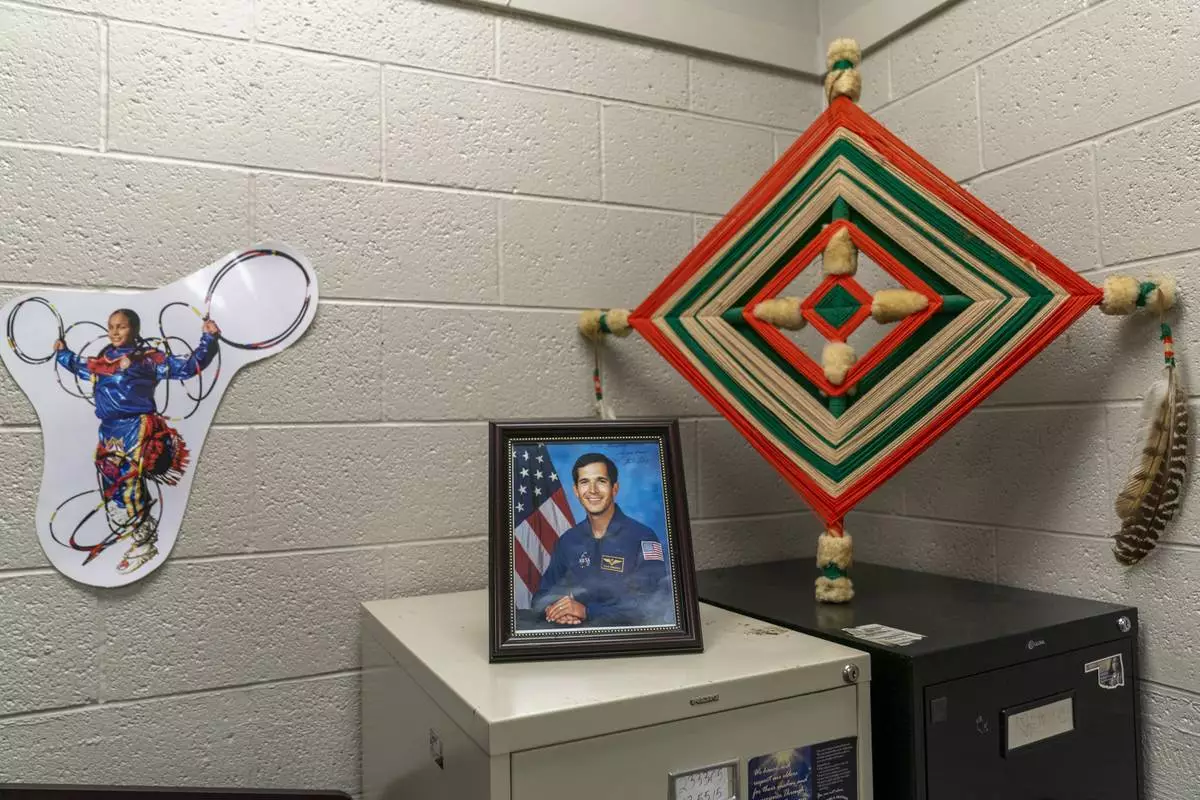

Decor adorns the corner of Indian Education Director Hollie Youngbear's office at Watonga High School Wednesday, Oct. 2, 2024, in Watonga, Okla. (AP Photo/Nick Oxford)

About 14% of students at the Watonga High School on the Cheyenne-Arapaho reservation are Native American, Wednesday, Oct. 2, 2024, in Watonga, Okla. (AP Photo/Nick Oxford)

Senior Happy Belle Shortman, who is who is Kiowa, Cheyenne and Arapaho, poses for a portrait at Watonga High School on Wednesday, Oct. 2, 2024, in Watonga, Okla. (AP Photo/Nick Oxford)

The football team practices on a new field at Watonga High School, Wednesday, Oct. 2, 2024, where about 14% of students at the school on the Cheyenne-Arapaho reservation are Native American in Watonga, Okla. (AP Photo/Nick Oxford)

The cafeteria sits empty after lunch at Watonga High School on Wednesday, Oct. 2, 2024, in Watonga, Okla. (AP Photo/Nick Oxford)

Alternative Education Director Carrie Compton poses for portrait in her classroom at Watonga High School on Wednesday, Oct. 2, 2024, in Watonga, Okla. When students do not show up for school, Compton and Indian Education Director Hollie Youngbear take turns visiting their homes. (AP Photo/Nick Oxford)

Nationwide, Native students miss school far more frequently than their peers, but not at Watonga High School shown on Wednesday, Oct. 2, 2024, in Watonga, Okla. (AP Photo/Nick Oxford)

Indian Education Director Hollie Youngbear looks over a binder of info she compiles about her students in her office at Watonga High School on Wednesday, Oct. 2, 2024, in Watonga, Okla. Youngbear and her colleagues work to connect with families in a way that acknowledges the history and needs of Native communities. (AP Photo/Nick Oxford)

Indian Education Director Hollie Youngbear poses for a portrait at Watonga High School on Wednesday, Oct. 2, 2024, in Watonga, Okla. (AP Photo/Nick Oxford)

Indian Education Director Hollie Youngbear poses for a portrait at Watonga High School on Wednesday, Oct. 2, 2024, in Watonga, Okla. Youngbear and her colleagues work to connect with families in a way that acknowledges the history and needs of Native communities. (AP Photo/Nick Oxford)