Many moms-to-be opt for blood tests during pregnancy to check for fetal disorders such as Down syndrome. In rare instances, these tests can reveal something unexpected — hints of a hidden cancer in the woman.

In a study of 107 pregnant women whose test results were unusual, 52 were ultimately diagnosed with cancer. Most of them were treated and are now in remission, although seven with advanced cancers died.

"They looked like healthy, young women and they reported themselves as being healthy,” said Dr. Diana Bianchi, the senior author of the government study published Wednesday in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Of the discovered cancers, lymphoma blood cancers were the most common, followed by colon and breast cancers.

The blood test is called cell-free DNA sequencing. It looks for fetal problems in DNA fragments shed from the placenta into the mother’s bloodstream. It also can pick up DNA fragments shed by cancer cells.

Of the millions of pregnant women each year who have a cell-free DNA test, 1 in 10,000 will get a result back that is unusual and difficult to interpret, neither positive or negative for a fetal abnormality. This small number of people — perhaps only 250 a year in the U.S. — may be at risk for cancer.

“They and their care providers need to take the results seriously and have additional testing because in that population there is a 48% risk of cancer,” said Bianchi, who leads the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

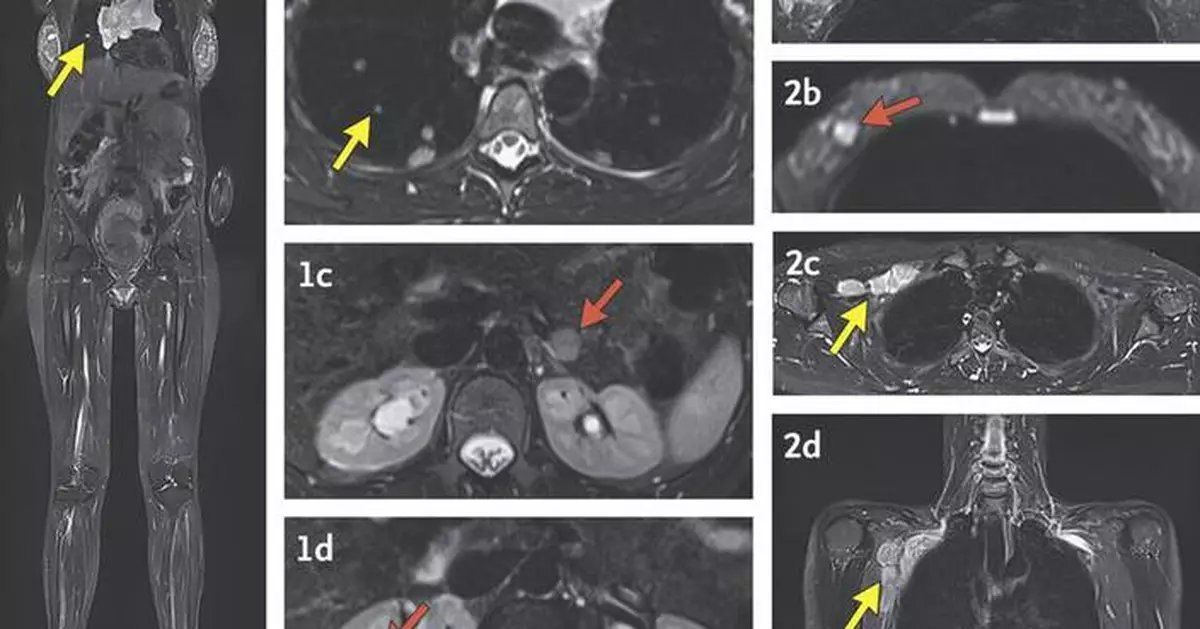

The study looked at what should be done next, and the researchers concluded that it's best to do a whole-body MRI to look for cancer. A physical exam or taking a family history is not enough, Bianchi said.

About five years ago, commercial labs that do these tests and doctors started telling women with unusual results about the study. The National Institutes of Health paid for study volunteers to travel to its research hospital in Bethesda, Maryland, where the participants had their family and medical histories reviewed, a complete physical examination, whole-body MRI scans and other tests performed.

The research identified a recognizable “very chaotic” pattern in the DNA sequencing of the women diagnosed with cancer, Bianchi said. The study is continuing to look for more evidence to indicate who should be screened for cancer.

Many medical groups now recommend offering cell-free DNA tests during pregnancy, though many expectant parents decide against the optional test. Considered reliable for detecting Down syndrome and two other disorders, the tests have come under scrutiny for too many false alarms for extremely rare fetal problems.

The new finding will help educate doctors about a rare result of DNA tests in pregnancy, said Dr. Neeta Vora, director of reproductive genetics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who wrote an editorial in the journal.

Doctors who care for pregnant women are not accustomed to ordering whole-body MRI tests, Vora said, and these scans, which can cost $1,000 to $2,000, may not be covered by health insurance.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

These MRI images with arrows indicating cancer were made during a study by researchers at the National Institutes of Health and published Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024, in the New England Journal of Medicine. (The New England Journal of Medicine via AP)

NEW YORK (AP) — Brian Thompson led one of the biggest health insurers in the U.S. but was unknown to millions of people his decisions affected.

Then Wednesday's targeted fatal shooting of the UnitedHealthcare CEO on a midtown Manhattan sidewalk thrust the executive and his business into the national spotlight.

Thompson, who was 50, had worked at the giant UnitedHealth Group Inc for 20 years and run the insurance arm since 2021 after running its Medicare and retirement business.

As CEO, Thompson led a firm that provides health coverage to more than 49 million Americans — more than the population of Spain. United is the largest provider of Medicare Advantage plans, the privately run versions of the U.S. government’s Medicare program for people age 65 and older. The company also sells individual insurance and administers health-insurance coverage for thousands of employers and state-and federally funded Medicaid programs.

The business run by Thompson brought in $281 billion in revenue last year, making it the largest subsidiary of the Minnetonka, Minnesota-based UnitedHealth Group. His $10.2 million annual pay package, including salary, bonus and stock options awards, made him one of the company's highest-paid executives.

The University of Iowa graduate began his career as a certified public accountant at PwC and had little name recognition beyond the health care industry. Even to investors who own its stock, the parent company's face belonged to CEO Andrew Witty, a knighted British triathlete who has testified before Congress.

When Thompson did occasionally draw attention, it was because of his role in shaping the way Americans get health care.

At an investor meeting last year, he outlined his company's shift to “value-based care,” paying doctors and other caregivers to keep patients healthy rather than focusing on treating them once sick.

“Health care should be easier for people,” Thompson said at the time. “We are cognizant of the challenges. But navigating a future through value-based care unlocks a situation where the … family doesn’t have to make the decisions on their own.”

Thompson also drew attention in 2021 when the insurer, like its competitors, was widely criticized for a plan to start denying payment for what it deemed non-critical visits to hospital emergency rooms.

“Patients are not medical experts and should not be expected to self-diagnose during what they believe is a medical emergency,” the chief executive of the American Hospital Association wrote in an open letter addressed to Thompson. “Threatening patients with a financial penalty for making the wrong decision could have a chilling effect on seeking emergency care.”

United Healthcare responded by delaying rollout of the change.

Thompson, who lived in a Minneapolis suburb and was the father of two high-school students, was set to speak at an investor meeting in a midtown New York hotel. He was on his own and about to enter the building when he was shot in the back by a masked assailant who fled on foot, the New York Police Department said.

Chief of Detectives Joseph Kenny said investigators were looking at Thompson's social media accounts and interviewing employees and family members.

“Didn’t seem like he had any issues at all,” Kenny said. "He did not have a security detail.”

AP reporters Michael R. Sisak and Steve Karnowski contributed to this report. Murphy reported from Indianapolis.

This combination of images provided by the New York City Police Department shows the suspect sought in the the killing of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson outside a Manhattan hotel where the health insurer was holding an investor conference, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024. (New York City Police Department via AP)

The UnitedHealthcare headquarters in Minnetonka, Minn., lowered its flags to half-staff on Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024, in honor of CEO Brian Thompson, who was fatally shot outside a hotel in New York. (Kerem Yücel/Minnesota Public Radio via AP)

This undated photo provided by UnitedHealth Group shows UnitedHealthcare chief executive officer Brian Thompson. (AP Photo/UnitedHealth Group via AP)