DEARBORN, Mich. (AP) — Nizam Abazid is gleefully planning his first trip in decades to Syria, where he grew up. Rama Alhoussaini was only 6 years old when her family moved to the U.S., but she's excited about the prospect of introducing her three kids to relatives they've never met in person.

They are among thousands of Detroit-area Syrian Americans who are celebrating the unexpected overthrow of the Syrian government, which crushed dissent and imprisoned political enemies with impunity during the more than 50-year reign of ousted President Bashar Assad and his father before him.

“As of Saturday night, the Assad regime is no longer in power,” Alhoussaini, 31, said through tears Tuesday at one of the Detroit-area school and day care facilities her family operates. “And it’s such a surreal moment to even say that out loud, because I never thought that I would see this day.”

It may be some time before either visits Syria. Though happy to see Assad go, many Western countries are waiting for the dust to settle before committing to a Syria strategy, including whether it’s safe for the millions who fled the country’s civil war to return.

Ahmad al-Sharaa, who led the insurgency that toppled Assad after an astonishing advance that took less than two weeks, has disavowed his group's former ties to al-Qaida and cast himself as a champion of pluralism and tolerance. But the U.S. still labels him a terrorist and warns against any travel to Syria, where the U.S. hasn't had an embassy since 2012, the year after the war started.

But for Syrians in the U.S. who have been unable to visit, the overthrow of the Assad government has given them hope that they can safely return, either for good or to visit.

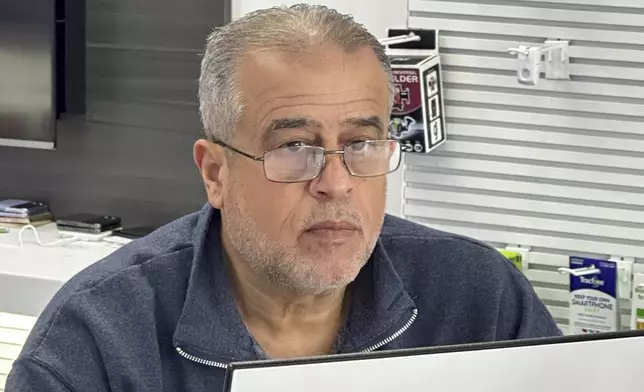

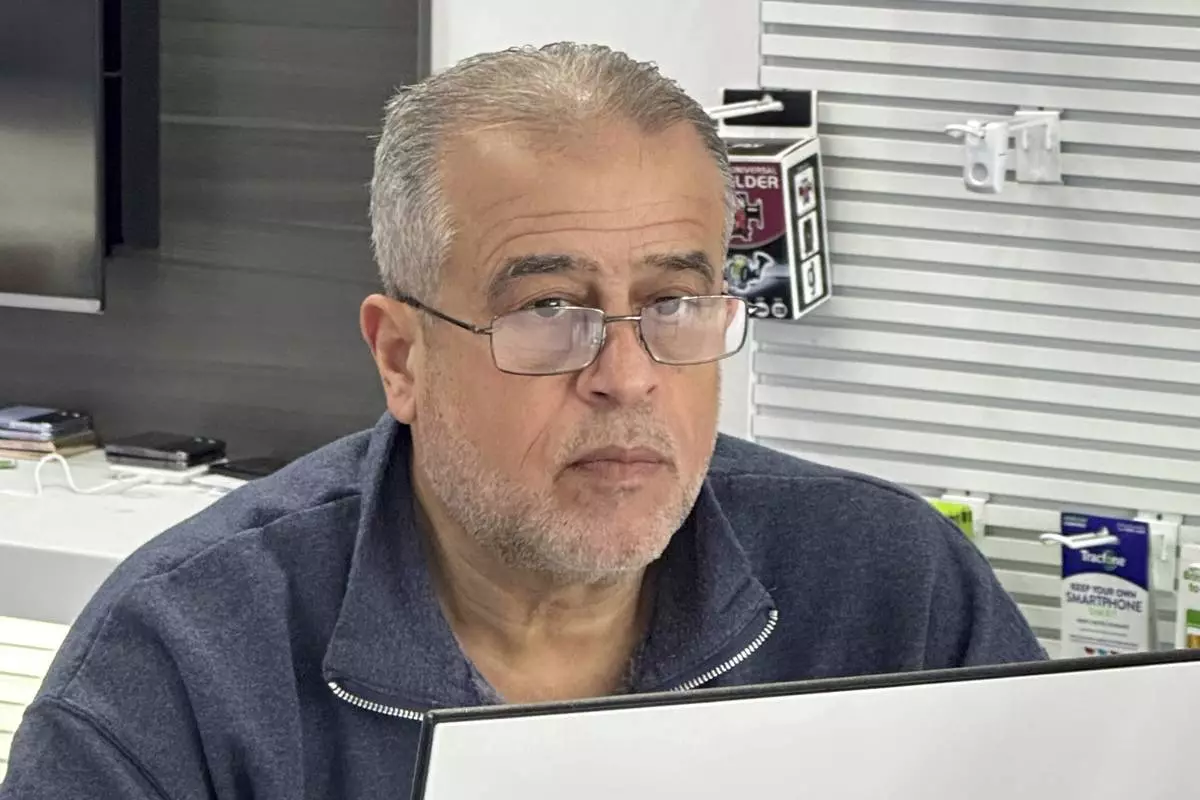

“The end of the regime is the hope for all the Syrian people,” Abazid said this week, days after Assad and his family fled to Russia.

Abazid said he could go to Syria whenever, since he holds dual U.S. and Syrian citizenship, but that he'll wait a few months for things there to settle down.

Although European leaders have said it's not safe enough yet to allow war-displaced refugees to return to Syria, Abazid said he and his brother aren't concerned.

“When Assad’s forces were in power, my fate would’ve been in jail or beheaded,” Abazid said. “But now, I will not be worried about that anymore.”

Many Syrians who immigrated to the U.S. settled in the Detroit area. Michigan has the largest concentration of Arab Americans of any state and is home to the country's largest Arab-majority city, Dearborn. It also has more than 310,000 residents who are of Middle Eastern or North African descent.

As rebel forces seized control of Syria, capping a lightning-quick advance that few thought possible even a month ago, Syrians in and around Detroit — like their counterparts all over the world — followed along in disbelief as reports poured in about one city after another slipping from Assad's grip. When news broke that Assad's government had fallen, celebrations erupted.

Abazid, who owns a cellphone business in Dearborn, was born in Daraa, about 60 miles (95 kilometers) south of the Syrian capital, Damascus. He moved to the U.S. in 1984 at age 18, and although he's gone back a few times, he hasn't visited since 1998 because of what he described as “harassment” by Syrian intelligence. That trip had to be heavily coordinated with U.S. authorities, as he said Syrian authorities took him into custody and detained him for more than six months during a 1990 visit.

“When I was kidnapped from the airport, my family didn’t even know ... what it was about," he told The Associated Press on Tuesday. "I still don’t know the reason. I have no idea why I was kidnapped.”

Abazid, 59, said his parents have died since that 1998 trip, but his five sisters still live in Syria. Each of his four brothers left Syria during the 1970s and 1980s, including one who hasn't been back since emigrating 53 years ago, shortly after Bashar Assad's father, Hafez al-Assad, rose to power.

Alhoussaini, who lives in West Bloomfield Township, said she was born in Damascus and moved to the Detroit area as a young girl, “mainly because there was nothing left for us in Syria.”

She said under the Assad family's rule, her grandfather's land was taken. Authorities detained him for almost a month. Her father was also detained before the family left.

“There never needed to be a reason,” Alhoussaini said. "My dad was able to return one time, in 2010. And he has not been able to go back to his home country since, mainly because we spoke up against the Assad regime when the revolution started in 2011. And we attended many protests here. We were vocal on social media about it, did many interviews.”

But with Bashar Assad gone and Syria in the hands of the rebels, “We don’t have to be afraid anymore to visit our country,” she said.

Her father, 61, is considering making a trip to Syria to see his siblings and visit his parents' graves. Alhoussaini said she and her husband, who is from the northern city of Aleppo, want to take their kids over to visit with family and friends.

Alhoussaini’s three sisters, ages 40, 34 and 29, were also born in Syria. But none of them have been back.

Now, there is hope and amazement that people in Syria can celebrate in the streets, she said.

Alhoussaini said she thinks people who were born and raised in the U.S. won't be able to fully relate, because Americans enjoy a freedom of expression that people in Syria have never had.

“You can say what you want. You can go out into the street and protest whoever you want,” she said. "You will not be detained for it. You will not be killed for it.”

Rama Alhoussaini sits at her desk in Dearborn Heights, Mich., Tuesday, Dec. 10, 2024. (AP Photo/Corey Williams)

Nizam Abazid sits in his cellular shop in Dearborn, Mich., Tuesday, Dec. 10, 2024. (AP Photo/Corey Williams)

Rama Alhoussaini stands in her office in Dearborn Heights, Mich., Tuesday, Dec. 10, 2024. (AP Photo/Corey Williams)

Nizam Abazid sits in his cellular shop in Dearborn, Mich., Tuesday, Dec. 10, 2024. Abazid, 59, left Syria in 1984. (AP Photo/Corey Williams)

Rama Alhoussaini holds a Syrian flag in her Dearborn Heights, Mich., office, Tuesday, Dec. 10, 2024. (AP Photo/Corey Williams)