SEOUL, South Korea (AP) — South Korea’s opposition leader offered Sunday to work with the government to ease the political tumult as officials sought to reassure allies and markets, a day after the opposition-controlled parliament voted to impeach conservative President Yoon Suk Yeol over a short-lived attempt to impose martial law.

Liberal Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung, whose party holds a majority in the National Assembly, urged the Constitutional Court to rule swiftly on Yoon's impeachment and proposed a special council for cooperation between the government and parliament.

Click to Gallery

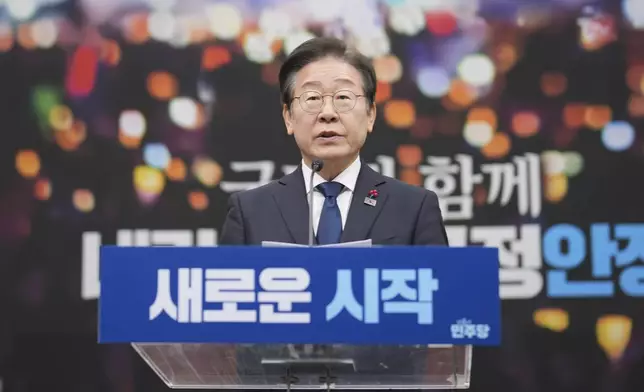

South Korea's main opposition Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung speaks during a press conference on removal of President Yoon Suk Yeol from office, at the party office at the National Assembly building in Seoul, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 15, 2024. (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

South Korea's main opposition Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung speaks during a press conference on removal of President Yoon Suk Yeol from office, at the party office at the National Assembly building in Seoul, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 15, 2024. (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

South Korea's main opposition Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung speaks during a press conference on removal of President Yoon Suk Yeol from office, at the party office at the National Assembly building in Seoul, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 15, 2024. (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

South Korea's main opposition Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung speaks during a press conference on removal of President Yoon Suk Yeol from office, at the party office at the National Assembly building in Seoul, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 15, 2024. (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

South Korea's main opposition Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung speaks during a press conference on removal of President Yoon Suk Yeol from office, at the party office at the National Assembly building in Seoul, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 15, 2024. (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

People attend at a rally to demand South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol's impeachment outside the National Assembly in Seoul, South Korea, Saturday, Dec. 14, 2024. The letters read "Impeachment." (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

In this photo released by South Korean President Office via Yonhap, South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol bows while delivering a speech at the presidential residence in Seoul, South Korea, after South Korea’s parliament voted to impeach Yoon Saturday, Dec. 14, 2024. (South Korean Presidential Office/Yonhap via AP)

South Korea's main opposition Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung, front left, and its floor leader Park Chan-dae, front right, leave a room at the National Assembly in Seoul after South Korea’s parliament voted to impeach President Yoon Suk Yeol Saturday, Dec. 14, 2024. (Kyodo News via AP)

South Korea's main opposition Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung, bottom center, and his party members bow at the National Assembly in Seoul, South Korea, after South Korea’s parliament voted to impeach President Yoon Suk Yeol Saturday, Dec. 14, 2024. (Kim Ju-hyung/Yonhap via AP)

Yoon's powers have been suspended until the court decides whether to remove him from office or reinstate him. If Yoon is dismissed, a national election to choose his successor must be held within 60 days.

Lee, who has led a fierce political offensive against Yoon's embattled government, is seen as the frontrunner to replace him.

He told a televised news conference that a swift court ruling would be the only way to “minimize national confusion and the suffering of people.”

The court will meet to begin considering the case Monday, and has up to 180 days to rule. But observers say that a court ruling could come faster. In the case of parliamentary impeachments of past presidents — Roh Moo-hyun in 2004 and Park Geun-hye in 2016, the court spent 63 days and 91 days respectively before determining to reinstate Roh and dismiss Park.

Lee also proposed a national council where the government and the National Assembly would work together to stabilize state affairs, and said his party won't seek to impeach the prime minister, a Yoon appointee who's now serving as acting president.

“The Democratic Party will actively cooperate with all parties to stabilize state affairs and restore international trust,” Lee said. “The National Assembly and government will work together to quickly resolve the crisis that has swept across the Republic of Korea.”

It wasn’t immediately clear how the governing People Power Party would react to Lee’s proposal. Kim Woong, a former PPP lawmaker, accused Lee of attempting to exert power over state affairs.

The Democratic Party has used its parliamentary majority to impeach the justice minister and the chief of the national police over the martial law decree, and previously said it was also considering impeaching Prime Minister Han Duck-soo.

There was no immediate response from Han, a seasoned bureaucrat.

Upon assuming his role as acting leader, Han ordered the military to bolster its security posture to prevent North Korea from launching provocations. He also asked the foreign minister to inform other countries that South Korea’s major external policies will remain unchanged, and the finance minister to work to minimize potential negative impacts on the economy by the political turmoil.

On Sunday, Han had a phone call with U.S. President Joe Biden, discussing the political situation in South Korea and regional security challenges including North Korea’s nuclear program. Biden expressed his appreciation for the resiliency of democracy in South Korea and reaffirmed “the ironclad commitment” of the United States, according to both governments.

Yoon’s Dec. 3 imposition of martial law, the first of its kind in more than four decades, lasted only six hours, but has caused massive political tumult, halted diplomatic activities and rattled financial markets. Yoon was forced to lift his decree after parliament unanimously voted to overturn it.

Yoon sent hundreds of troops and police officers to the parliament in an effort to stop the vote, but they withdrew after the parliament rejected Yoon’s decree. No major violence occurred.

Opposition parties have accused Yoon of rebellion, saying a president in South Korea is allowed to declare martial law only during wartime or similar emergencies and would have no right to suspend parliament’s operations even in those cases.

Yoon has rejected the charges and vowed to “fight to the end." He said the deployment of troops to parliament was aimed to issue a warning to the Democratic Party, which he called an “anti-state force” that abused its control of parliament by holding up the government’s budget bill for next year and repeatedly pushing to impeach top officials.

Law enforcement institutions are investigating possible rebellion and other allegations. They've arrested Yoon's defense minister and police chief and two other high-level figures.

Yoon has immunity from most criminal prosecution as president, but that doesn’t extend to allegations of rebellion or treason. He's been banned from leaving South Korea, but observers doubt that authorities will detain him because of the potential for clashes with his presidential security service.

Lee called for authorities to speed up their probes and said that an independent investigation by a special prosecutor should be launched as soon as possible. Last week, the National Assembly passed a law calling for an investigation led by a special prosecutor.

“Individuals and institutions involved in this act of rebellion should fully cooperate with the investigations,” Lee said.

South Korea's main opposition Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung speaks during a press conference on removal of President Yoon Suk Yeol from office, at the party office at the National Assembly building in Seoul, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 15, 2024. (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

South Korea's main opposition Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung speaks during a press conference on removal of President Yoon Suk Yeol from office, at the party office at the National Assembly building in Seoul, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 15, 2024. (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

South Korea's main opposition Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung speaks during a press conference on removal of President Yoon Suk Yeol from office, at the party office at the National Assembly building in Seoul, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 15, 2024. (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

South Korea's main opposition Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung speaks during a press conference on removal of President Yoon Suk Yeol from office, at the party office at the National Assembly building in Seoul, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 15, 2024. (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

South Korea's main opposition Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung speaks during a press conference on removal of President Yoon Suk Yeol from office, at the party office at the National Assembly building in Seoul, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 15, 2024. (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

People attend at a rally to demand South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol's impeachment outside the National Assembly in Seoul, South Korea, Saturday, Dec. 14, 2024. The letters read "Impeachment." (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

In this photo released by South Korean President Office via Yonhap, South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol bows while delivering a speech at the presidential residence in Seoul, South Korea, after South Korea’s parliament voted to impeach Yoon Saturday, Dec. 14, 2024. (South Korean Presidential Office/Yonhap via AP)

South Korea's main opposition Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung, front left, and its floor leader Park Chan-dae, front right, leave a room at the National Assembly in Seoul after South Korea’s parliament voted to impeach President Yoon Suk Yeol Saturday, Dec. 14, 2024. (Kyodo News via AP)

South Korea's main opposition Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung, bottom center, and his party members bow at the National Assembly in Seoul, South Korea, after South Korea’s parliament voted to impeach President Yoon Suk Yeol Saturday, Dec. 14, 2024. (Kim Ju-hyung/Yonhap via AP)

DAMASCUS (AP) — The new head of security arrived at Damascus’ international airport with his men, a bearded fighter who marched with other rebels across Syria to the capital. The few maintenance staff who showed up for work huddled around Maj Hamza al-Ahmed, eager for answers about what happens next.

They unloaded all their complaints, pent up for years during the rule of President Bashar Assad, which now, inconceivably, is over.

They told him they were denied promotions and perks funneled to pro-Assad favorites, that bosses threatened them with prison for working too slowly. They warned him of hardcore Assad supporters among the airport staff, ready to return whenever the facility reopens.

As al-Ahmed tried to reassure them, Osama Najm, an engineer, confessed: “This is the first time we talk.”

This was the first week of Syria’s transformation after Assad’s unexpected fall.

Rebels, suddenly in charge, met a population bursting with emotions: excitement at new freedoms; grief over years of repression; and hopes, expectations and worries about the future. Some were overwhelmed to the point of tears.

The transition has been surprisingly smooth. Reports of reprisals, revenge killings and sectarian violence have been minimal. Looting and destruction have been quickly contained, insurgent fighters disciplined. On Saturday, people went about their lives as usual in the capital, Damascus. Only a single van of fighters was seen.

There are a million ways it could go wrong.

The country is broken and isolated after five decades of Assad family rule. Families have been torn apart by war, former prisoners are traumatized by the brutalities they suffered, tens of thousands of detainees remain missing. The economy is wrecked, poverty is widespread, inflation and unemployment are high. Corruption seeps through daily life.

But in this moment of flux, many are ready to feel out the way ahead.

At the airport, al-Ahmed told the staffers: “The new path will have challenges, but that is why we have said Syria is for all and we all have to cooperate.”

The rebels have so far said all the right things, Najm said. “But we will not be silent about anything wrong again.”

At a torched police station, pictures of Assad were torn down and files destroyed after insurgents entered the city Dec. 8. All Assad-era police and security personnel have vanished.

On Saturday, the building was staffed by 10 men serving in the police force of the rebels’ de facto “salvation government,” which for years governed the rebel enclave of Idlib in Syria’s northwest.

The rebel policemen watch over the station, dealing with reports of petty thefts and street scuffles. One woman complains that her neighbors sabotaged her power supply. A policeman tells her to wait for courts to start operating again.

“It will take a year to solve problems” he mumbled.

The rebels sought to bring order in Damascus by replicating the structure of its governance in Idlib. But there is a problem of scale. One of the policemen estimates the number of rebel police at only around 4,000; half are based in Idlib and the rest are tasked with maintaining security in Damascus and elsewhere. Some experts estimate the insurgents’ total fighting force at around 20,000.

Most of the bearded fighters hail from conservative, provincial areas. Many are hardline Islamists.

The main insurgent force, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, has renounced its al-Qaida past, and its leaders are working to reassure Syria’s religious and ethnic communities that the future will be pluralist and tolerant.

Syrians remain suspicious.

“The people we see on the streets, they don’t represent us,” said Hani Zia, a Damascus resident. He was concerned by the few reports of attacks on minorities and revenge killings. “We should be fearful.”

Some restaurants have resumed openly serving alcohol, others more discretely to test the mood.

At a sidewalk café in the historic Old City’s Christian quarter, men were drinking beer when a fighter patrol passed by. The men turned to each other, uncertain, but the fighters did nothing. When a man waving a gun harassed a liquor store elsewhere in the Old City, the rebel police arrested him, one policeman said.

Salem Hajjo, a theater teacher who participated in the 2011 protests, said he doesn’t agree with the rebels’ Islamist views, but is impressed at their experience in running their own affairs. And he expects to have a voice in the new Syria.

“We have never been this at ease,” he said. “The fear is gone. The rest is up to us.”

On the night after Assad’s fall, gunmen roamed the streets, celebrating victory with deafening gunfire. Some security agency buildings were torched. The public stayed indoors.

Hayat Tahrir al-Sham moved to impose order. It ordered a nighttime curfew for three days. It banned celebratory gunfire and moved fighters to protect properties.

After a day, people began to emerge.

Tens of thousands went to Assad’s prisons to search for loved ones, mingling with rebels, some of whom were also searching.

Amid celebrations, gunmen invited children to hop up on their armored vehicles, and posed for photos with women, some with their hair uncovered. Pro-revolution songs blared from cars.

The transitional government urged people to return to work. The insurgents deployed men to act as traffic police. Volunteers picked up trash, since municipal workers haven’t returned to their jobs.

Officials say they want to reopen the airport as soon as possible and this week maintenance crews inspected a handful of planes on the tarmac. Cleaners removed trash, wrecked furniture and merchandise.

One cleaner, who identified himself only as Murad, said he earns the equivalent of $15 a month and has six children to feed, including one with a disability. He dreams of getting a mobile phone.

“We need a long time to clean this up,” he said.

Associated Press writer Ghaith Alsayed contributed.

A Syrian fighter holds a gun with a flower placed in the barrel, as people gather for Friday prayers at the Umayyad mosque in Damascus, Syria, Friday, Dec. 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Leo Correa)

A woman weeps during the funeral of Syrian activist Mazen al-Hamada in Damascus, Thursday, Dec. 12, 2024. Al-Hamad's mangled corpse was found wrapped in a bloody sheet in Saydnaya prison. He had fled to Europe but returned to Syria in 2020 and was imprisoned upon arrival. (AP Photo/Hussein Malla)

A man waves a flare during a celebratory demonstration following the first Friday prayers since Bashar Assad's ouster, in Damascus' central square, Syria, Friday, Dec. 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Leo Correa)

Syrians gather during a celebratory demonstration following the first Friday prayers since Bashar Assad's ouster, in Damascus' central square, Syria, Friday, Dec. 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)

Syrians display a giant Syrian "revolutionary" flag during a celebratory demonstration following the first Friday prayers since Bashar Assad's ouster, in Damascus' central square, Syria, Friday, Dec. 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Ghaith Alsayed)