After the busy Black Friday holiday weekend, Kristen Tarnol, owner of Emerald City Gifts in Studio City, California, is already asking her supplier to send more more fuzzy alpaca scarves and warm slippers that were best sellers over the weekend.

“Even though it’s Los Angeles … I think people are looking for cozy items, really,” she said.

Click to Gallery

A person shops at Serendipity, Wednesday, Dec. 11, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Matt Slocum)

Nicole Beltz adjusts hats on display at her shop, Serendipity, Wednesday, Dec. 11, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Matt Slocum)

People walk past Serendipity, Wednesday, Dec. 11, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Matt Slocum)

Nicole Beltz poses for a photograph at her shop, Serendipity, Wednesday, Dec. 11, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Matt Slocum)

A person walks past Between Friends Boutique, Wednesday, Dec. 11, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Matt Slocum)

Manager Deborah Averette steams clothing at Between Friends Boutique, Wednesday, Dec. 11, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Matt Slocum)

Claudia Averette lays out clothing at her shop, Between Friends Boutique, Wednesday, Dec. 11, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Matt Slocum)

Claudia Averette, left, and her daughter, Atiya Smith pose for a photograph at their shop, Between Friends Boutique, Wednesday, Dec. 11, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Matt Slocum)

With a late Thanksgiving, the holiday shopping season is five days shorter than last year, and owners of small retail shops say people have been quick to snap up holiday décor early, along with gifts for others and themselves. Cozy items like sweaters are popular so far. But there’s little sense of the freewheeling spending that occurred during the pandemic.

Overall, The National Retail Federation predicts retail sales in November and December will rise between 2.5% and 3.5% compared with same period a year ago. Online shopping is expected to grow too. Adobe Digital Insights, a division of software company Adobe, predicts an 8.4% increase online for the full season.

Some owners say shopping has been erratic so far this holiday season. Nathan Waldon, who owns Nathan & Co., with two gift shops in Oakland, California, said he had his best Black Friday ever, with sales up 32%. But business slowed dramatically after that. He’s hoping it picks up again soon.

“I still feel like I’m optimistic for the season,” he said. “But it’s definitely going to be one of those roller coaster seasons again.”

He said comforting items are selling: Scarves, hats and gloves, humorous Christmas and Hanukkah cards and bright colors.

“People want that sense of whimsy, that sense of fun,” he said. ”A couple of seasons ago everything was sort of muted and earthy, and now everyone is craving happy colors.”

One of his top sellers is a bright pink sweater with the word “Merry” written in big letters that sells for $120. But generally, shoppers are looking to spend less than half of that, he said.

“It could be they could buy the $25 item, but then they’ll add on a little something extra,” he said. “It seems to me that the sweet spot is between 40 and 50 bucks.”

Small businesses in some parts of the country are hoping holiday shopping helps them recover from extreme weather during the year. In Florida, Jennifer Johnson, owner of consignment shop True Fashionistas in Naples, Florida, had a slow summer season, partly because the area was hit by three hurricanes this year. She decided to increase her Black Friday weekend discount this year to draw in shoppers – offering a 25%-off deal rather than the 18% to 20% she normally offers.

It worked. The store had record sales days over the weekend. People snapped up festive Christmas outfits and Christmas décor. The Christmas décor, including ornaments, candles and other home decorations, is selling faster than last year, she said.

“Last year we were out of Christmas stuff like by the second week of December, and we’re almost out of it now and it’s only the first week of December,” Johnson said.

As for clothing: “anything sequins, anything that has had bedazzling on it, anything that looks fine and festive is what they were buying,” she said.

At her three Philadelphia-area Serendipity shops that sell clothing, accessories and home goods, owner Nicole Beltz also faced weather-related challenges in foot traffic over the year, including snow in the first quarter, a lot of rain in the second quarter and extreme heat in the third quarter. An unpredictable economy and tough competition on pricing from bigger chains were also obstacles during the year.

During the Black Friday weekend, she offered 20% off for orders of $75 or more and 30% off orders of $150 and more. Last year she just offered discounts on select items, not blanket discounts.

“We gave out our biggest incentive ever for shoppers to come out with discounts and promos. I certainly think that that was necessary this year,” she said.

Beltz’ customers gravitated toward prices either under $20 or around $100. At her shops, Philadelphia Eagles and Taylor Swift merchandise were the top sellers, including $14 socks and $99 sweaters.

“One is the impulse category, where if it’s under $20, they’ll buy it. No matter what,” she said. “And then the second category would be for really people that are coming in looking for a gift. We’re pushing the $100 sale. We try to keep our best sellers, like those sweaters and those items that people are really grabbing for a nice holiday gift at $99, right under the $100 mark.”

Not all small businesses can use discounts to drive business, since margins are often tight.

Between Friends Boutique in Philadelphia is using events to drive holiday traffic instead. They held a “Sweater Explosion” event at 8 a.m. on Black Friday where they served hot apple cider and hot chocolate with marshmallows and promoted different styles of sweaters.

Sweaters under $100 were big sellers, along with $25 reversible silk scarves that feature art from impressionists like Monet.

“Our customers appreciated that little extra touch of laughs during the holidays. Coming in and smelling the cinnamon in the air felt like the holidays have arrived,” co-owner Claudia Averette said. Sales are up so far from last year, she added.

They’re also hosting a “Bourbon and Bow Tie” event on Dec. 20 to promote the fact that they carry men’s accessories as well, like bow ties, socks and scarves.

An event helps get exposure, Averette said. “It’s a great marketing strategy,” she said.

A person shops at Serendipity, Wednesday, Dec. 11, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Matt Slocum)

Nicole Beltz adjusts hats on display at her shop, Serendipity, Wednesday, Dec. 11, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Matt Slocum)

People walk past Serendipity, Wednesday, Dec. 11, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Matt Slocum)

Nicole Beltz poses for a photograph at her shop, Serendipity, Wednesday, Dec. 11, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Matt Slocum)

A person walks past Between Friends Boutique, Wednesday, Dec. 11, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Matt Slocum)

Manager Deborah Averette steams clothing at Between Friends Boutique, Wednesday, Dec. 11, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Matt Slocum)

Claudia Averette lays out clothing at her shop, Between Friends Boutique, Wednesday, Dec. 11, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Matt Slocum)

Claudia Averette, left, and her daughter, Atiya Smith pose for a photograph at their shop, Between Friends Boutique, Wednesday, Dec. 11, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Matt Slocum)

SAN PEDRO SULA, Honduras (AP) — As dozens of deported migrants pack into a sweltering airport facility in San Pedro Sula, Norma sits under fluorescent lights clutching a foam cup of coffee and a small plate of eggs – all that was waiting for her in Honduras.

The 69-year-old Honduran mother had never imagined leaving her Central American country. But then came the anonymous death threats to her and her children and the armed men who showed up at her doorstep threatening to kill her, just like they had killed one of her relatives days earlier.

Norma, who requested anonymity out of concern for her safety, spent her life savings of $10,000 on a one-way trip north at the end of October with her daughter and granddaughter.

But after her asylum petitions to the U.S. were rejected, they were loaded onto a deportation flight. Now, she's back in Honduras within reach of the same gang, stuck in a cycle of violence and economic precarity that haunts deportees like her.

“They can find us in every corner of Honduras,” she said in the migrant processing facility. “We’re praying for God’s protection, because we don’t expect anything from the government.”

Now, as U.S. President-elect Donald Trump is set to take office in January with a promise of carrying out mass deportations, Honduras and other Central American countries people have fled for generations are bracing for a potential influx of vulnerable migrants — a situation they are ill-prepared to handle.

Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador, which have the largest number of people living illegally in the U.S., after Mexico, could be among the first and most heavily impacted by mass deportations, said Jason Houser, former Immigration & Customs Enforcement chief of staff in the Biden administration.

Because countries like Venezuela refuse to accept deportation flights from the U.S., Houser suggests that the Trump administration may prioritize the deportation of “the most vulnerable” migrants from those countries who have removal orders but no criminal record, in an effort to rapidly increase deportation numbers.

“Hondurans, Guatemalans, Salvadorans need to be very, very nervous because (Trump officials) are going to press the bounds of the law,” said Houser.

Migrants and networks aiding deportees in those Northern Triangle countries worry their return could thrust them into even deeper economic and humanitarian crises, fueling migration down the line.

“We don’t have the capacity” to take so many people, said Antonio García, Honduras' deputy foreign minister. “There’s very little here for deportees." People who return, he said, "are the last to be taken care of.”

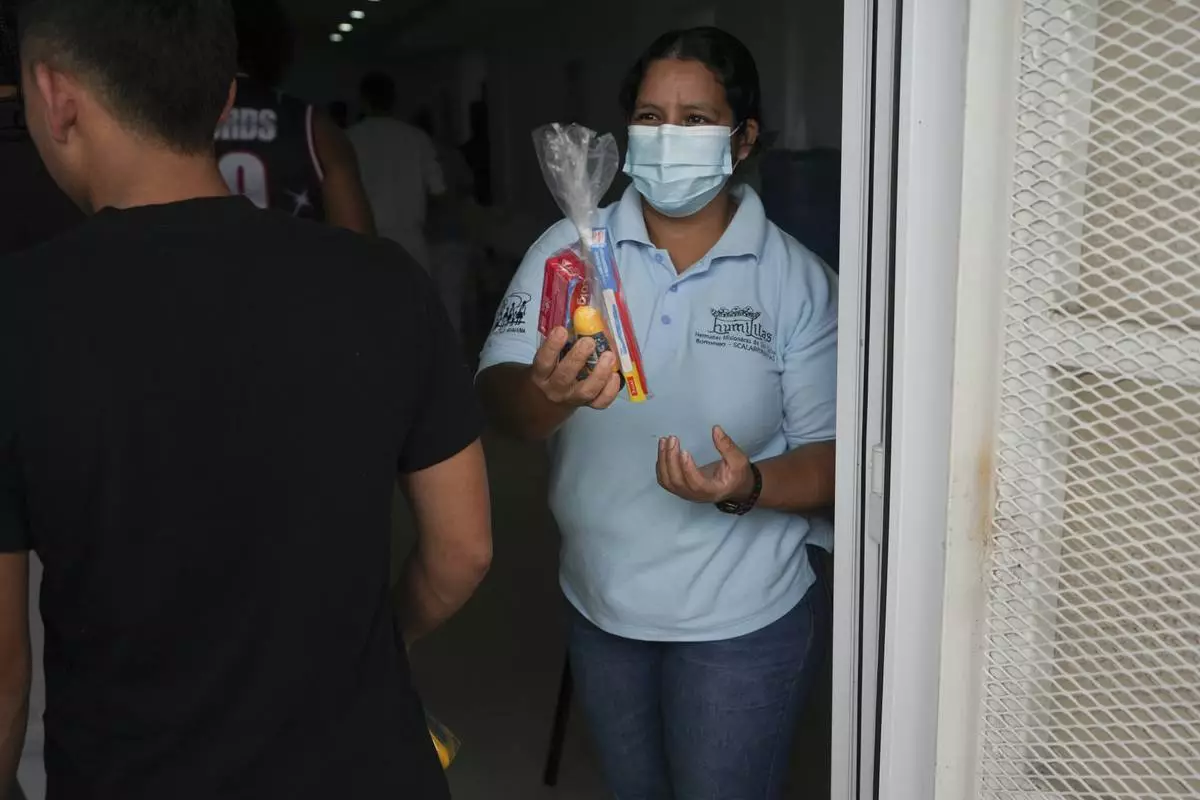

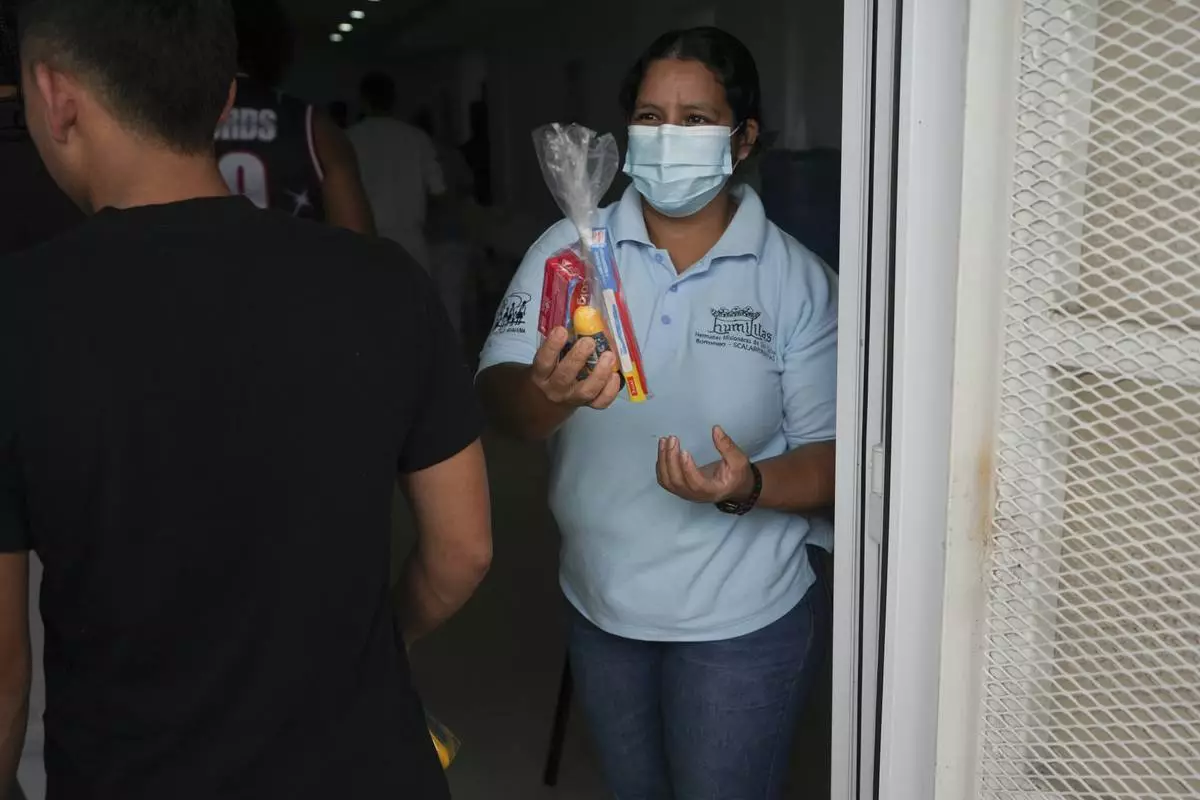

Since 2015, Honduras has received around half a million deportees. They climb down from planes and buses to be greeted with coffee, small plates of food and bags of toothpaste and deodorant. While some breathe a sigh of relief, free from harsh conditions in U.S. detention facilities, others cry, gripped with panic.

“We don’t know what we’ll do, what comes next,” said one woman in a cluster of deportees waiting for their names to be called by a man clacking at a keyboard.

Approximately 560,000 Hondurans, about 5% of the country's population, live in the U.S. without legal status, according to U.S. government figures. Of those, migration experts estimate about 150,000 can be tracked down and rapidly expelled.

While García said the government offers services to help returnees, most are released with little aid into a country gripped by gangs. They have few options for work to pay off crippling debts. Others like Norma have nowhere to go, unable to return home because of the gang members circling her home.

Norma said she’s unsure of why they were targeted, but she believes it was because the relative who was killed had problems with a gang.

Despite the crackdown, García estimates up to 40% of Honduran deportees make their way back to the U.S.

Larissa Martínez, 31, is among those who have struggled to reintegrate into Honduran society after being deported from the U.S. in 2021 with her three children. Driven by economic desperation and the absence of her husband, who had migrated and left her for another woman, the single mother sought a better life in the U.S.

Since her return to Honduras, Martínez has spent the past three years searching for a job, not just to support her kids, but also to pay off the $5,000 she owes to relatives for the trip north.

Her efforts have been unsuccessful. She built a wobbly wooden home tucked away in the hilly fringes of San Pedro Sula, where she sells meat and cheese to get by, but sales have been slim and tropical rains have eaten away at the flimsy walls where they sleep.

So she's begun to repeat a chant in her head: “If I don’t find work in December, I’ll leave in January.”

César Muñoz, a leader at Mennonite Social Action Commission, said Honduran authorities have abandoned deportees like Martínez, leaving organizations like his to step in. But with three deportation flights arriving weekly, aid networks are already stretched thin.

A significant uptick could leave aid networks, migrants and their families reeling. Meanwhile, countries like Honduras, heavily reliant on remittances from the U.S., could face severe economic consequences as this vital lifeline is cut.

“We’re at the brink of a new humanitarian crisis,” Muñoz said.

Trump’s return has been met with a range of reactions by Latin American nations connected to the U.S. through migration and trade.

Guatemala, a country with more than 750,000 citizens living unauthorized in the U.S. , announced in November it was working on a strategy to take on potential mass deportations. Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum said Mexico is already beefing up legal services in its U.S. consulates and that she would ask Trump to deport non-Mexicans directly to their countries of origin.

Honduras’ Deputy Foreign Minister García expressed skepticism about Trump’s threat, citing the economic benefits immigrants provide to the U.S. economy and the logistical challenges of mass deportations. Aid leaders like Muñoz say Honduras isn’t sufficiently preparing for a potential surge in deportations.

Even with a crackdown by Trump it would be “impossible” to stop people from migrating, García said. Driven by poverty, violence and the hope for a better life, clusters of deportees climb aboard buses on their way back to the U.S.

As deportations by both U.S. and Mexican authorities spike, smugglers are offering migrants packages in which they get three tries to make it north. If migrants get captured on their journey and sent back home, they still have two chances to get to the U.S.

Freshly returned to Honduras, 26-year-old Kimberly Orellana said she spent three months detained in a Texas facility before being sent back to San Pedro Sula, where she waited in a bus station for her mother to pick her up.

Yet, she was already planning to return, saying she had no choice: her 4-year-old daughter Marcelle was waiting for her, cared for by a friend in North Carolina.

The two were separated by smugglers crossing the Rio Grande, in hopes to increase their chances of successfully crossing over. Orellana vowed to her daughter that they would be reunited.

“Mami, are you sure you’re coming?” Marcelle asks her over the phone.

“Now, being here it’s difficult to know if I’ll ever be able to follow through with that promise,” Orellana said, clinging to her Honduran passport. “I have to try again. … My daughter is all I have.”

Follow AP’s coverage of Latin America and the Caribbean at https://apnews.com/hub/latin-america

A worker offers personal care kits to Honduran migrants who were deported from the U.S. after they landed at Ramon Villeda Morales Airport in San Pedro Sula, Honduras, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Moises Castillo)