WASHINGTON (AP) — Americans hoping for lower borrowing costs for homes, credit cards and cars may be disappointed after this week's Federal Reserve meeting. The Fed's policymakers are likely to signal fewer interest rate cuts next year than were previously expected.

The officials are set to reduce their benchmark rate, which affects many consumer and business loans, by a quarter-point to about 4.3% when their meeting ends Wednesday. At that level, the rate would be a full point below the four-decade high it reached in July 2023. The policymakers had kept their key rate at its peak for more than a year to try to quell inflation, until slashing the rate by a half-point in September and a quarter-point last month.

The problem is that while inflation has dropped far below its peak of 9.1% in mid-2022, it remains stubbornly above the Fed's 2% target. As a result, the Fed, led by Chair Jerome Powell, is expected Wednesday to signal a shift to a more gradual approach to rate cuts in 2025. Economists say that after cutting rates for three straight meetings, the central bank will likely do so at every other gathering, or possibly even less often than that.

“We’re on the cusp of a transition to them not cutting every meeting,” said David Wilcox, a former senior Fed official who is an economist with Bloomberg Economics and the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “They’re going to slow the tempo of cuts.”

The economy has fared better than officials expected it would as recently as September. And inflation pressures have proved more persistent. The presidential election added a wild card, too: President-elect Donald Trump has promised to enact policies — from much higher taxes on imports to mass deportations of people living illegally in the United States — that most economists say threaten to accelerate inflation.

“Growth is definitely stronger than we thought, and inflation is coming in a little higher,” Powell said recently. “So the good news is, we can afford to be a little more cautious" as the Fed's officials seek to lower rates to what they consider a “neutral” level — one that neither spurs nor restricts growth.

On Wednesday, the policymakers will also issue their quarterly projections for growth, inflation, unemployment and their benchmark interest rate over the next three years. In September, they had collectively envisioned that they'd cut rates four times next year. Economists now expect just two or three Fed rate cuts in 2025. Wall Street traders foresee even fewer: Just two cuts, according to futures prices.

Fewer rate cuts by the Fed would mean that households and businesses would continue to face loan rates, notably for home mortgages, that would far exceed their levels before inflation began surging more than three years ago.

Some economists question whether the Fed even needs to cut this week. Inflation, excluding volatile food and energy costs, has been stuck at an annual rate of about 2.8% since March. A year ago, the policymakers had forecast that that figure would have fallen to 2.4% by now and that they'd have cut their key rate by three-quarters of a point. Instead, inflation has become stuck at a higher level, yet the Fed has lowered its benchmark rate by a full point.

Fed officials, including Powell, have said they still foresee inflation heading lower, however slowly, while their key rate is still high enough to restrain growth. As a result, reducing rates this week is more akin to letting up on a brake than stepping on an accelerator.

The potential for major changes to tax, spending and immigration policies under Trump is another reason for the Fed to take a more cautious approach. Former Fed economists say the central bank's staff has likely begun factoring the effects of Trump's proposed corporate tax cuts into their economic analyses, but not his proposed tariffs or deportations, because those two policies are too difficult to assess without details.

Tara Sinclair, an economist at George Washington University who is a former Treasury Department official, suggested that the uncertainty surrounding whether Trump's policy changes will keep inflation elevated — and necessitating higher rates — could also lead the Fed to cut rates more gradually, if at all.

“It seems easier to explain not cutting than to find themselves in a position where they would have to raise rates in this political environment,” Sinclair said.

Powell has said the Fed is seeking to lower its rate to the so-called “neutral” level. Yet there is wide disagreement among the policymakers about how high that rate is. Many economists peg it at 3% to 3.5%. Some economists think it could be higher.

And Richard Clarida, a former vice chair of the Fed who is a managing director at PIMCO, said that if inflation becomes stuck above the Fed's target level, then the policymakers will likely keep rates above the neutral level.

During the July-September quarter, the economy expanded at a solid 2.8% annual rate. On Tuesday, the government will report the November retail sales figures, which are expected to show healthy consumer demand.

“There doesn’t seem to be any sign of weakness emerging overall,” said David Beckworth, a senior fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. “I don’t see in my mind the justification for rate cuts."

FILE - Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell speaks at the DealBook Summit in New York, on Dec. 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig, File)

SEOUL, South Korea (AP) — South Korea’s impeached President Yoon Suk Yeol dodged requests by investigative agencies to appear for questioning over his short-lived martial law decree, as the Constitutional Court began its first meeting Monday on Yoon's case to determine whether to formally unseat or reinstate him.

A joint investigative team involving police, an anti-corruption agency and the Defense Ministry said it wants to question Yoon on charges of rebellion and abuse of power in connection with his ill-conceived power grab.

The team on Monday tried to convey a request to officials at Yoon's office or residence but they refused to accept it, according to the Corruption Investigation Office for High-Ranking Officials.

Agency investigator Son Yeong-jo cited presidential secretarial staff at Yoon's office as claiming they were unsure whether conveying the request to the impeached president was part of their duties. Son said his team had also mailed the request to Yoon, but declined to provide specifics when asked how investigators would respond if Yoon refuses to appear.

Yoon was impeached by the opposition-controlled National Assembly on Saturday over his Dec. 3 martial law decree. His presidential powers have been subsequently suspended, and the Constitutional Court is to determine whether to formally remove him from office or reinstate him. If Yoon is dismissed, a national election to choose his successor must be held within 60 days.

Yoon has justified his martial law enforcement as a necessary act of governance against the main liberal opposition Democratic Party that he described as “anti-state forces” bogging down his agendas and vowed to “fight to the end” against efforts to remove him from office.

Hundreds of thousands of protesters have poured onto the streets of the country’s capital, Seoul, in recent days, calling for Yoon’s ouster and arrest.

It remains unclear whether Yoon will grant the request by investigators for an interview. South Korean prosecutors, who are pushing a separate investigation into the incident, also reportedly asked Yoon to appear at a prosecution office for questioning on Sunday but he refused to do so. Repeated calls to a prosecutors’ office in Seoul were unanswered.

Yoon’s presidential security service has also resisted a police attempt to search Yoon's office for evidence.

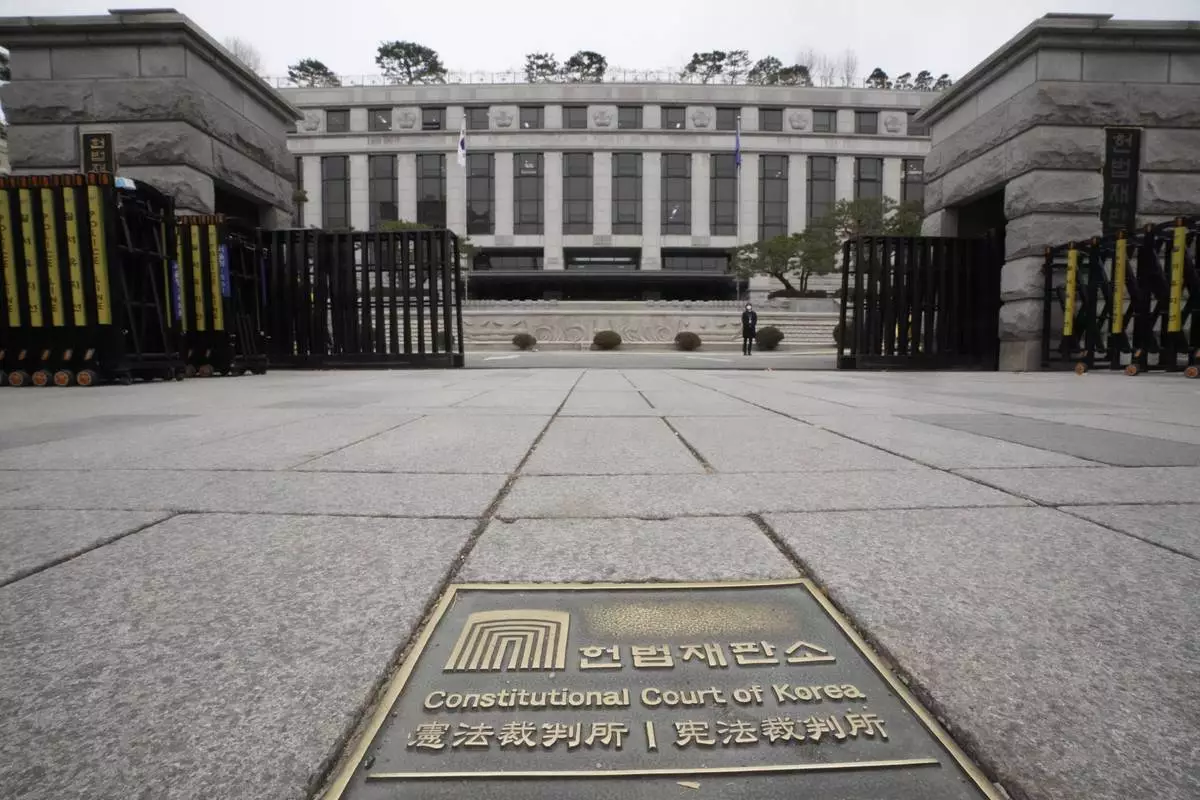

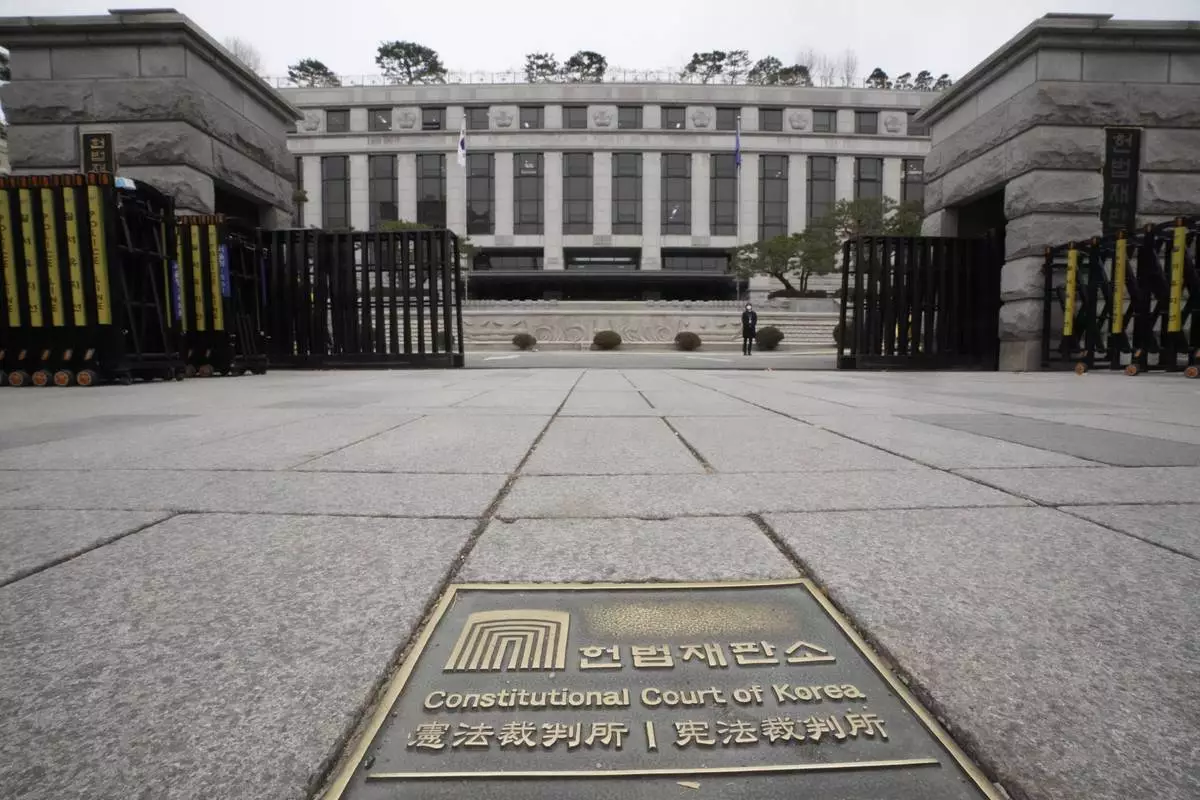

The Constitutional Court on Monday met for the first time to discuss the case. The court has up to 180 days to rule. But observers say a ruling could come faster.

In the case of parliamentary impeachments of past presidents — Roh Moo-hyun in 2004 and Park Geun-hye in 2016 — the court spent 63 days and 91 days respectively before determining to reinstate Roh and dismiss Park.

Kim Hyungdu, a court justice, told reporters earlier Monday that the court will “swiftly and fairly” make a decision in the case. He said Monday’s court meeting was meant to discuss preparatory procedures and how to arrange arguments at formal trials.

Court spokesperson Lee Jean later said the court's first pretrial hearing is set for Dec. 27.

Upholding Yoon’s impeachments needs support from at least six out of the court’s nine justices, but three seats are vacant now. This means a unanimous ruling by the court’s current six justices in favor of Yoon's impeachment is required to formally end his presidency. Kim said he expected the three vacant seats to be filled by the end of this month.

Prime Minister Han Duck-soo, who became the country’s acting leader after Yoon's impeachment, and other government officials have sought to reassure allies and markets after Yoon’s surprise stunt paralyzed politics, halted high-level diplomacy and complicated efforts to revive a faltering economy.

Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung urged the Constitutional Court to rule swiftly on Yoon’s impeachment and proposed a special council for policy cooperation between the government and parliament. Yoon’s conservative People Power Party criticized Lee’s proposal for the special council, saying that it’s “not right” for the opposition party to act like the ruling party.

Lee, a firebrand lawmaker who drove a political offensive against Yoon’s government, is seen as the frontrunner to replace him. He lost the 2022 presidential election to Yoon by a razor-thin margin.

Yoon’s impeachment, which was endorsed in parliament by some of his ruling party lawmakers, has created a deep rift within the party between Yoon’s loyalists and his opponents. On Monday, PPP chair Han Dong-hun, a strong critic of Yoon's martial law, announced his resignation.

“If martial law had not been lifted that night, a bloody incident could have erupted that morning between the citizens who would have taken to the streets and our young soldiers,” Han told a news conference.

Yoon’s Dec. 3 imposition of martial law, the first of its kind in more than four decades, harkened back to an era of authoritarian leaders the country has not seen since the 1980s. Yoon was forced to lift his decree hours later after parliament unanimously voted to overturn it.

Yoon sent hundreds of troops and police officers to the parliament in an effort to stop the vote, but they withdrew after the parliament rejected Yoon’s decree. No major violence occurred.

Opposition parties have accused Yoon of rebellion, saying a president in South Korea is allowed to declare martial law only during wartime or similar emergencies and would have no right to suspend parliament’s operations even in those cases.

In this photo released by South Korean President Office via Yonhap, South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol speaks at the presidential residence in Seoul, South Korea, Saturday, Dec. 14, 2024. (South Korean Presidential Office/Yonhap via AP)

A worker places a wreath sent by supporters for impeached South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol outside the Constitutional Court in Seoul, South Korea, Monday, Dec. 16, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

Lee Jin, spokeswoman of the South Korean Constitutional Court, speaks during a press conference at the court in Seoul, South Korea, Monday, Dec. 16, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

A sign of the Constitutional Court is seen on the ground in front of the court's building in Seoul, South Korea, Monday, Dec. 16, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

Supporters for impeached South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol stage rally against his impeachment near the Constitutional Court in Seoul, South Korea, Monday, Dec. 16, 2024. The signs read "Oppose the impeachment of President Yoon Suk Yeol." (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

Supporters for impeached South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol stage a rally against his impeachment near the Constitutional Court in Seoul, South Korea, Monday, Dec. 16, 2024. The signs read "Oppose the impeachment of President Yoon Suk Yeol." (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

South Korea's ruling People Power Party leader Han Dong-hun speaks during a news conference to announce his resignation after President Yoon Suk Yeol's parliamentary impeachment, at the National Assembly in Seoul, South Korea, Monday, Dec. 16, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

South Korea's ruling People Power Party leader Han Dong-hun speaks during a news conference to announce his resignation after President Yoon Suk Yeol's parliamentary impeachment, at the National Assembly in Seoul, South Korea, Monday, Dec. 16, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

South Korea's ruling People Power Party leader Han Dong-hun reacts during a news conference to announce his resignation after President Yoon Suk Yeol's parliamentary impeachment, at the National Assembly in Seoul, South Korea, Monday, Dec. 16, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

Participants shout slogans during a rally calling on the Constitutional Court to dismiss the President Yoon Suk Yeol in Seoul, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 15, 2024. The signs read "Immediately arrest." (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

Participants shout slogans during a rally calling on the Constitutional Court to dismiss the President Yoon Suk Yeol, in Seoul, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 15, 2024. The signs read "Immediately arrest." (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

Participants shout slogans during a rally calling on the Constitutional Court to dismiss the President Yoon Suk Yeol, in Seoul, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 15, 2024. The signs read "Immediately arrest." (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

In this photo released by South Korean President Office via Yonhap, South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol bows while delivering a speech at the presidential residence in Seoul, South Korea, after South Korea’s parliament voted to impeach Yoon Saturday, Dec. 14, 2024. (South Korean Presidential Office/Yonhap via AP)

South Korea's main opposition Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung speaks during a press conference on removal of President Yoon Suk Yeol from office, at the party office at the National Assembly building in Seoul, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 15, 2024. (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

Participants hold signs during a rally calling on the Constitutional Court to dismiss the President Yoon Suk Yeol in Seoul, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 15, 2024. The signs read "Immediately arrest." (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)