TOMS RIVER, N.J. (AP) — Years of toxic waste dumping in a Jersey Shore community where childhood cancer rates rose caused at least $1 billion in damage to natural resources, according to an environmental group trying to overturn a settlement between New Jersey and the corporate successor to the firm that did the polluting.

Save Barnegat Bay and the township of Toms River are suing to overturn a deal between the state and German chemical company BASF under which the firm will pay $500,000 and carry out nine environmental remediation projects at the site of the former Ciba-Geigy Chemical Corporation plant.

Click to Gallery

A gate blocks entrance to the former Ciba-Geigy chemical plant Dec. 17, 2024, in Toms River, N.J., one of America's worst toxic waste sites. (AP Photo/Wayne Parry)

A gate blocks entrance to the former Ciba-Geigy chemical plant Dec. 17, 2024, in Toms River, N.J., one of America's worst toxic waste sites. (AP Photo/Wayne Parry)

Water sits in a lined pit at the former Ciba-Geigy chemical plant on Dec. 17, 2024, in Toms River, N.J., one of America's most notorious toxic waste sites. (AP Photo/Wayne Parry)

Water sits in a lined pit at the former Ciba-Geigy chemical plant on Dec. 17, 2024, in Toms River, N.J., one of America's most notorious toxic waste sites. (AP Photo/Wayne Parry)

FILE - A sculpture of a grieving mother at a memorial garden in Toms River, N.J., for children who died from any cause is shown on Feb. 21, 2023. (AP Photo/Wayne Parry, File)

Trees are reflected in the slow-moving Toms River on Feb. 21, 2023, where the former Ciba-Geigy Chemical Corp. dumped toxic waste for decades. (AP Photo/Wayne Parry)

That site became one of America's worst toxic waste dumps and led to widespread concern over the prevalence of childhood cancer cases in and around Toms River.

Save Barnegat Bay says the settlement is woefully inadequate and does not take into account the scope and full nature of the pollution.

The state Department of Environmental Protection defended the deal, saying it is not supposed to be primarily about monetary compensation; restoring damaged areas is a priority, it says.

“Ciba-Geigy’s discharges devastated the natural resources of the Toms River and Barnegat Bay,” said Michele Donato, an attorney for the environmental group. “The DEP failed to evaluate decades of evidence, including reports of dead fish, discolored waters, and toxic effluent, that exist in its own archived files.”

Those materials include documents dating back to 1958 detailing fish kills and severe oxygen depletion caused by the company's dumping of chemicals into the Toms River and directly onto the ground. It also includes a study by a consultant for Ciba-Geigy showing that a plume of contaminated underground water is three-dimensional and thus could not be adequately assessed by the manner used by New Jersey to calculate damage to natural resources, the group said.

An accurate calculation of damages to the site and the surrounding area would exceed $1 billion, Save Barnegat Bay said in court papers.

"This deal does not come close to compensating our community for what we’ve suffered,” former Toms River Mayor Maurice Hill said in a January public hearing on the settlement.

The state declined to comment. In court papers, it defended its handling of the damage assessment.

BASF, which is the corporate successor to Ciba-Geigy, declined comment on the litigation but said it is committed to carrying out the settlement it reached with New Jersey in 2022.

That calls for it to maintain nine projects for 20 years, including restoring wetlands and grassy areas; creating walking trails, boardwalks and an elevated viewing platform; and building an environmental education center.

Starting in the 1950s, Ciba-Geigy — which had been the town’s largest employer — flushed chemicals into the Toms River and the Atlantic Ocean, and buried 47,000 drums of toxic waste in the ground. This created a plume of polluted water that has spread beyond the site into residential neighborhoods and is still being cleaned up.

The state health department found that 87 children in Toms River, which was then known as Dover Township, had been diagnosed with cancer from 1979 through 1995. A study determined the rates of childhood cancers and leukemia in girls in Toms River “were significantly elevated when compared to state rates.” No similar rates were found for boys.

The study did not explicitly blame the increase on Ciba-Geigy’s dumping, but the company and two others paid $13.2 million to 69 families whose children were diagnosed with cancer. Ciba-Geigy settled criminal charges by paying millions of dollars in fines and penalties on top of the $300 million it and its successors have paid so far to clean up the site.

Follow Wayne Parry on X at www.twitter.com/WayneParryAC

A gate blocks entrance to the former Ciba-Geigy chemical plant Dec. 17, 2024, in Toms River, N.J., one of America's worst toxic waste sites. (AP Photo/Wayne Parry)

A gate blocks entrance to the former Ciba-Geigy chemical plant Dec. 17, 2024, in Toms River, N.J., one of America's worst toxic waste sites. (AP Photo/Wayne Parry)

Water sits in a lined pit at the former Ciba-Geigy chemical plant on Dec. 17, 2024, in Toms River, N.J., one of America's most notorious toxic waste sites. (AP Photo/Wayne Parry)

Water sits in a lined pit at the former Ciba-Geigy chemical plant on Dec. 17, 2024, in Toms River, N.J., one of America's most notorious toxic waste sites. (AP Photo/Wayne Parry)

FILE - A sculpture of a grieving mother at a memorial garden in Toms River, N.J., for children who died from any cause is shown on Feb. 21, 2023. (AP Photo/Wayne Parry, File)

Trees are reflected in the slow-moving Toms River on Feb. 21, 2023, where the former Ciba-Geigy Chemical Corp. dumped toxic waste for decades. (AP Photo/Wayne Parry)

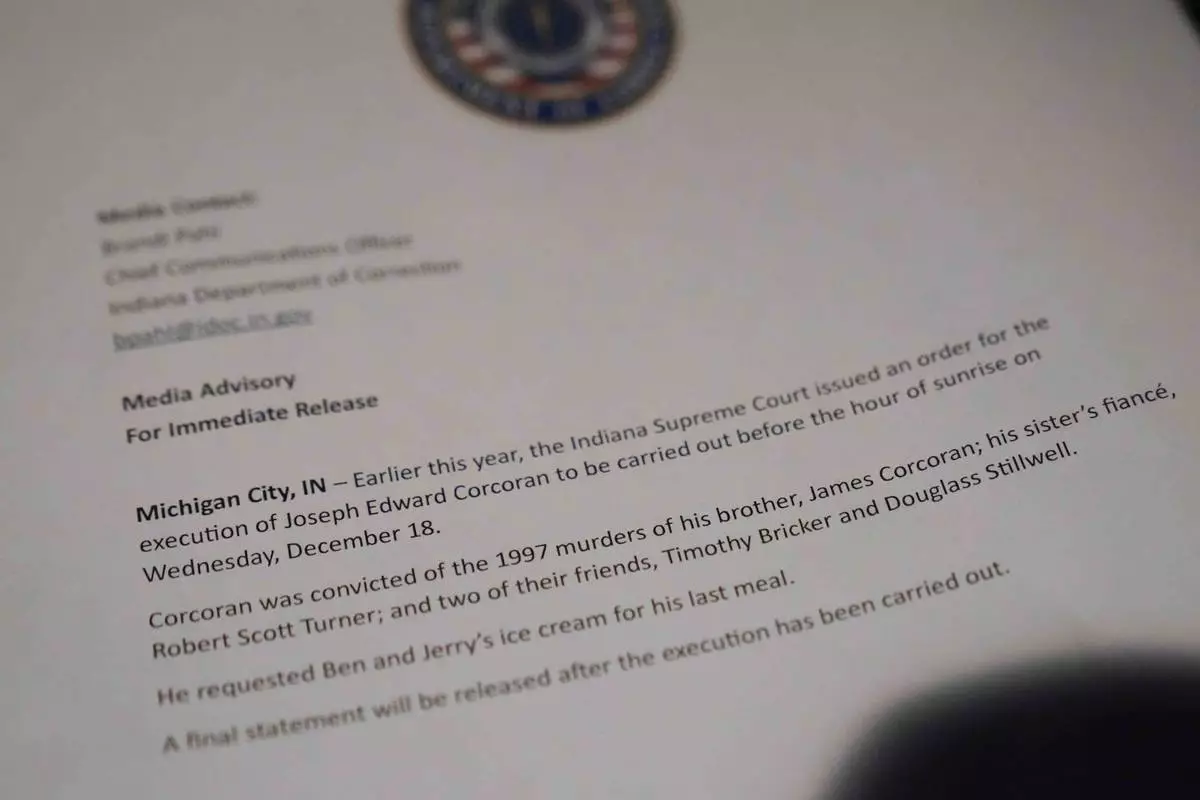

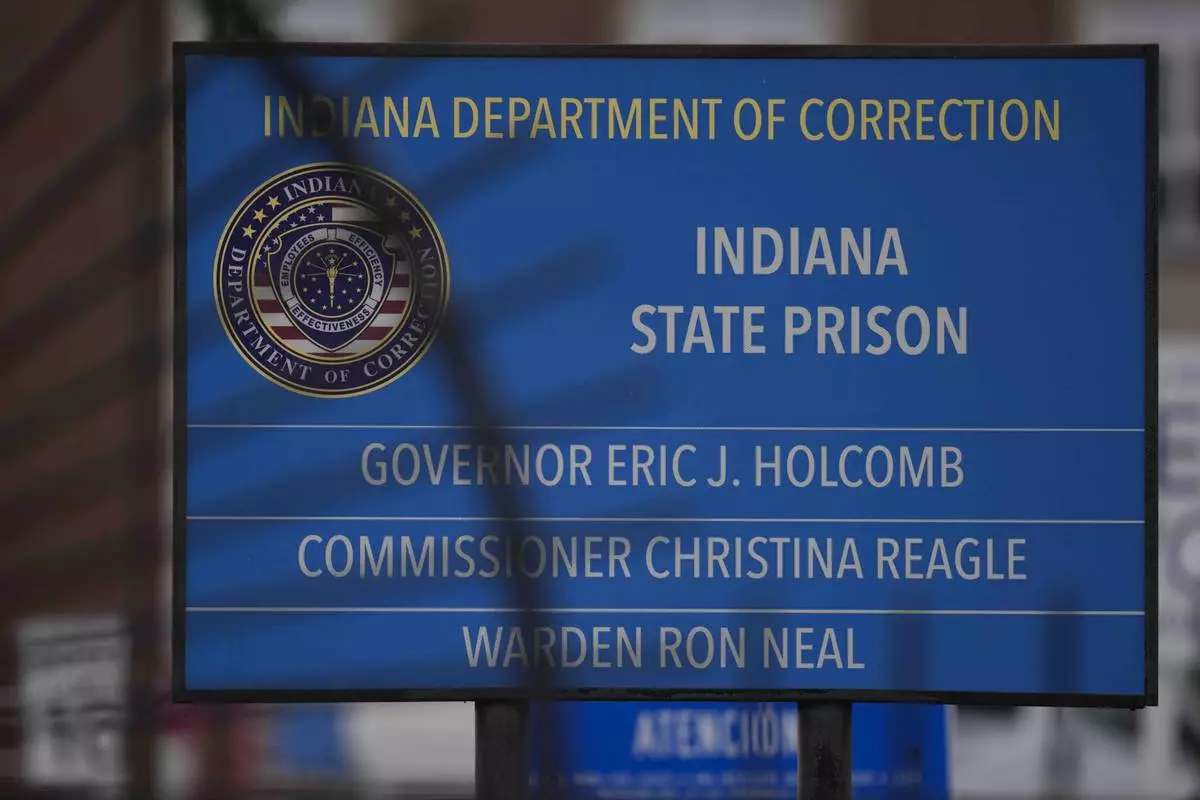

MICHIGAN CITY, Ind. (AP) — An Indiana man convicted of killing four people including his brother and his sister’s fiancé decades ago was put to death Wednesday, marking the state’s first execution in 15 years.

Joseph Corcoran, 49, was pronounced dead at 12:44 a.m. CST at the Indiana State Prison in Michigan City, Indiana, the Indiana Department of Correction said in a statement. Corcoran was scheduled to be executed with the powerful sedative pentobarbital, but the state agency’s statement did not mention that drug. Corcoran’s execution was the 24th in the U.S. this year.

The state provided limited details about the execution process, and no media witnesses were permitted under state law. However, Corcoran chose a reporter for the Indiana Capital Chronicle as one of his witnesses, the outlet’s editor posted on X early Wednesday.

Four people viewed the execution through a window in a small adjacent room, said Corcoran attorney Larry Komp. He said he, a reporter from Indiana Capital Chronicle and two family members were witnesses. The death took eight minutes, but Komp said he only had a partial view and he could not hear anything, including any last words.

Komp said “there was no way to tell” if Corcoran was in pain.

Indiana and Wyoming are the only two states that do not allow members of the media to witness state executions, according to a recent report by the Death Penalty Information Center.

Corcoran was convicted in the July 1997 shootings of his brother, 30-year-old James Corcoran, his sister’s fiancé, 32-year-old Robert Scott Turner, and two other men, Timothy G. Bricker, 30, and Douglas A. Stillwell, 30.

According to court records, before Corcoran fatally shot the four victims he was under stress because the forthcoming marriage of his sister to Turner would necessitate moving out of the Fort Wayne, Indiana, home he shared with his brother and sister.

While jailed for those killings, Corcoran reportedly bragged about fatally shooting his parents in 1992 in northern Indiana’s Steuben County. He was charged in their killings but acquitted.

Last summer, Gov. Eric Holcomb announced plans to resume state executions following a yearslong hiatus marked by a scarcity of lethal injection drugs nationwide.

Corcoran’s attorneys had fought his death penalty sentence for years, arguing he was severely mentally ill, which affected his ability to understand and make decisions. This month his attorneys asked the Indiana Supreme Court to stop his execution but the request was denied.

Corcoran exhausted his federal appeals in 2016. But his attorneys asked the U.S. District Court of Northern Indiana last week to stop his execution and hold a hearing to decide if it would be unconstitutional because Corcoran has a serious mental illness. The court declined to intervene Friday, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit did the same Tuesday.

Corcoran’s attorneys then asked the U.S. Supreme Court issue an emergency order halting his execution, but the high court denied their request for a stay late Tuesday, ending Corcoran’s options with the courts.

Komp said that he was disappointed with the high court’s decision, adding that the question of Corcoran’s mental health was not properly evaluated.

“There has never been a hearing to determine whether is he competent to be executed,” he said in a statement to The Associated Press. “It is an absolute failure for the rule of law to have an execution when the law and proper processes were not followed.”

Corcoran's sole remaining hope then became Holcomb, who could have commuted Corcoran’s death sentence. But that commutation never came and the execution proceeded as scheduled.

At midnight, a group of activists who oppose the death penalty began singing “Amazing Grace.”

Holcomb's office released a statement early Wednesday following Corcoran's execution.

“Joseph Corcoran’s case has been reviewed repeatedly over the last 25 years – including 7 times by the Indiana Supreme Court and 3 times by the U.S. Supreme Court, the most recent of which was tonight. His sentence has never been overturned and was carried out as ordered by the court,” Holcomb said in the statement.

Indiana’s last state execution was in 2009 when Matthew Wrinkles was put to death for killing his wife, her brother and sister-in-law in 1994. Since then, 13 executions were carried out in Indiana but those were initiated and performed by federal officials in 2020 and 2021 at a federal prison in Terre Haute.

State officials have said they couldn’t continue executions because a combination of drugs used in lethal injections had become unavailable.

For years, there has been a shortage across the country because pharmaceutical companies have refused to sell their products for that purpose. That’s pushed states, including Indiana, to turn to compounding pharmacies, which manufacture drugs specifically for a client. Some use more accessible drugs such as the sedatives pentobarbital or midazolam, both of which, critics say, can cause intense pain.

Religious groups, disability rights advocates and others have opposed his execution. About a dozen people, some holding candles, held a vigil late Tuesday to pray outside the prison, which is surrounded by barbed wire fences in a residential area about 60 miles (90 kilometers) east of Chicago.

“We can build a society without giving governmental authorities the right to execute their own citizens,” said Bishop Robert McClory of the Diocese of Gary, who led the prayers.

Other death penalty opponents also demonstrated outside the prison Tuesday night, some holding signs that read “Execution Is Not The Solution” and “Remember The Victims But Not With More Killing.”

“There is no need and no benefit from this execution. It’s all show,” said Abraham Borowitz, director of Death Penalty Action, his organization that protests every execution in the U.S.

Prison officials said in a brief statement Tuesday evening that Corcoran “requested Ben & Jerry’s ice cream for his last meal.”

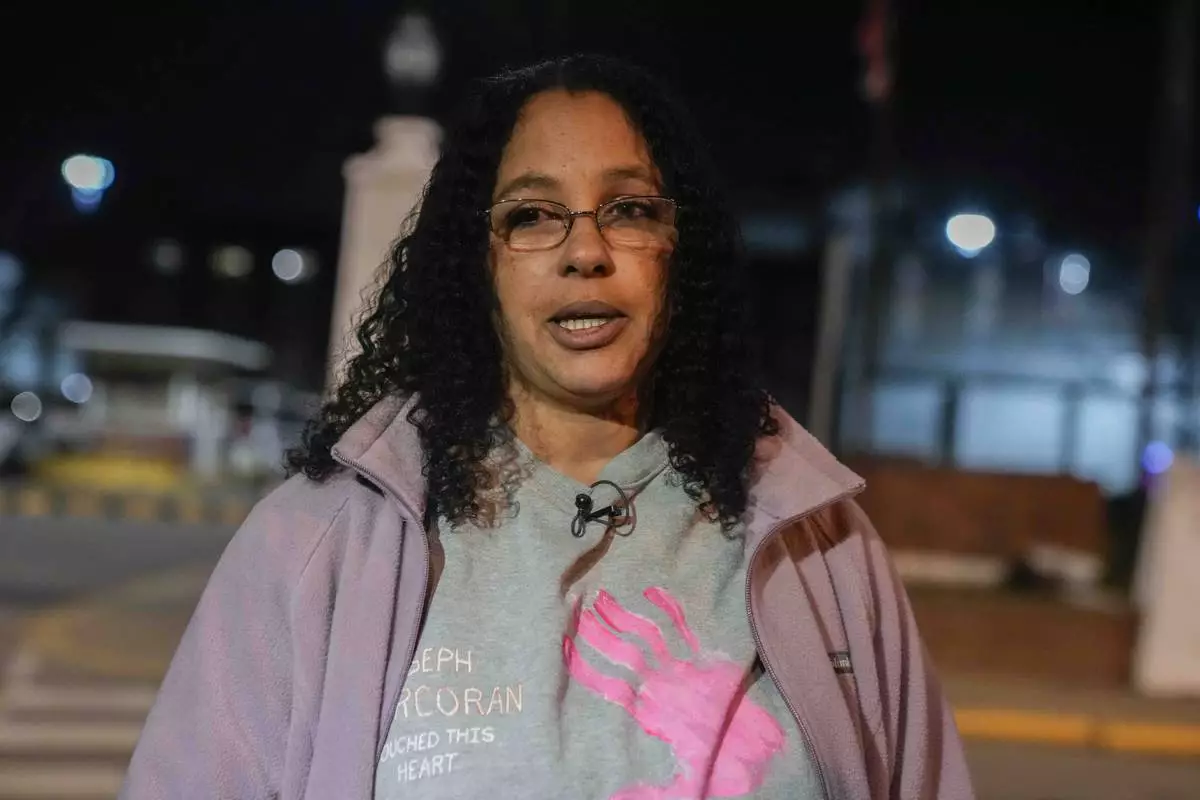

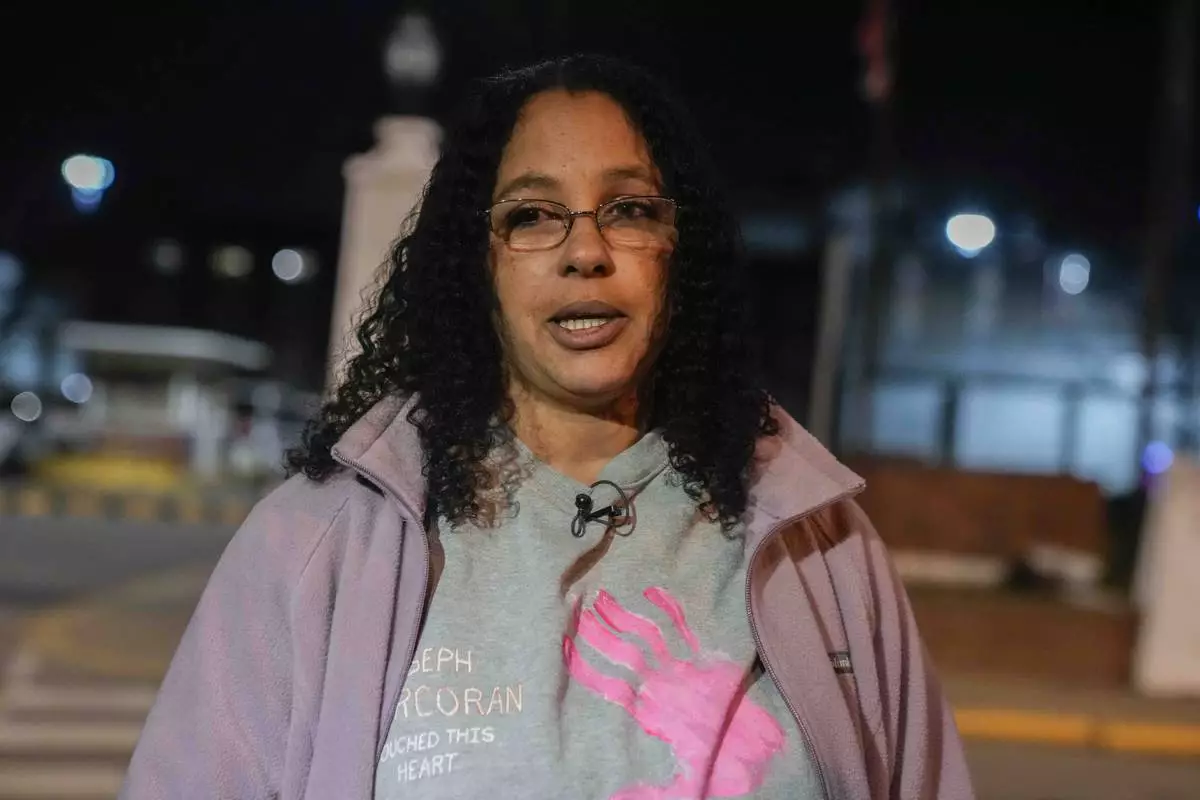

Corcoran said farewell late Tuesday to relatives, including his wife, Tahina Corcoran, who told reporters outside the prison that they discussed their faith and their memories, including attending high school together. She reiterated her request for Indiana’s governor to commute her husband’s death sentence.

Tahina Corcoran said her husband was “very mentally ill” and she didn't think he fully grasped what was happening to him.

“He is in shock. He doesn’t understand,” she said.

Callahan reported from Indianapolis.

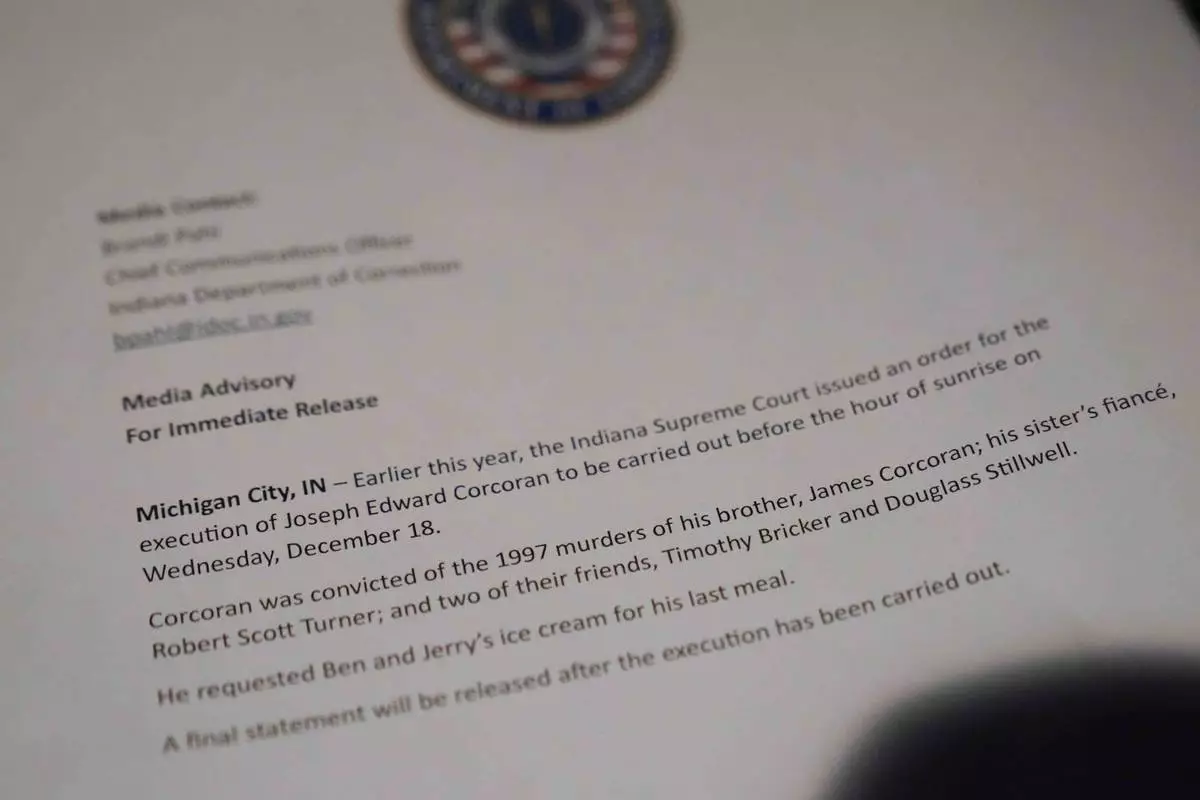

Officials deliver a paper statement outside of Indiana State Prison on Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024, in Michigan City, Ind., where, barring last-minute court action or intervention by Gov. Eric Holcomb, Joseph Corcoran, 49, convicted in the 1997 killings of his brother and three other people, is scheduled to be put to death by lethal injection before sunrise Wednesday, Dec. 18. (AP Photo/Erin Hooley)

Officials deliver a paper statement outside of Indiana State Prison on Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024, in Michigan City, Ind., where, barring last-minute court action or intervention by Gov. Eric Holcomb, Joseph Corcoran, 49, convicted in the 1997 killings of his brother and three other people, is scheduled to be put to death by lethal injection before sunrise Wednesday, Dec. 18. (AP Photo/Erin Hooley)

Calling herself his wife, Tahina Corcoran speaks outside of Indiana State Prison on Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024, in Michigan City, Ind., where, barring last-minute court action or intervention by Gov. Eric Holcomb, Joseph Corcoran, 49, convicted in the 1997 killings of his brother and three other people, is scheduled to be put to death by lethal injection before sunrise Wednesday, Dec. 18. (AP Photo/Erin Hooley)

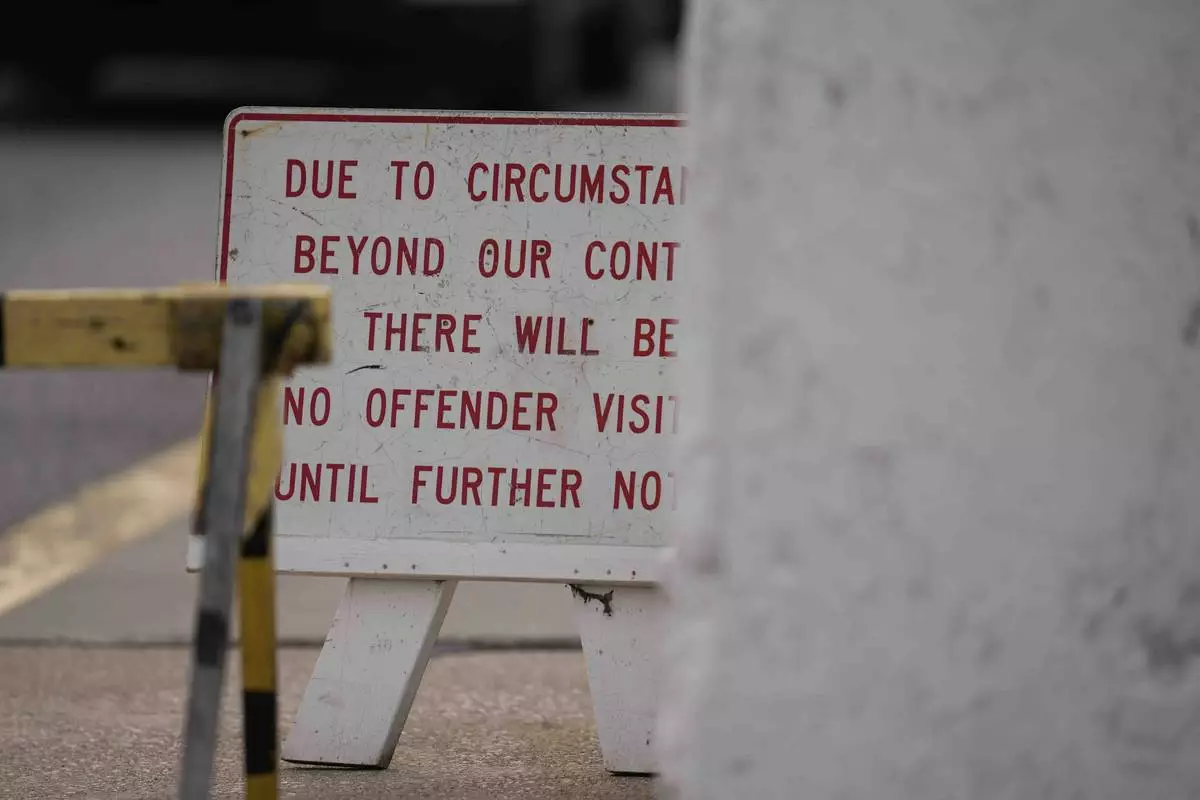

A sign is posted outside of Indiana State Prison on Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024, in Michigan City, Ind., where, barring last-minute court action or intervention by Gov. Eric Holcomb, Joseph Corcoran, 49, convicted in the 1997 killings of his brother and three other people, is scheduled to be put to death by lethal injection before sunrise Wednesday, Dec. 18. (AP Photo/Erin Hooley)

A police officer walks outside of Indiana State Prison on Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024, in Michigan City, Ind., where, barring last-minute court action or intervention by Gov. Eric Holcomb, Joseph Corcoran, 49, convicted in the 1997 killings of his brother and three other people, is scheduled to be put to death by lethal injection before sunrise Wednesday, Dec. 18. (AP Photo/Erin Hooley)

People enter Indiana State Prison on Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024, in Michigan City, Ind., where, barring last-minute court action or intervention by Gov. Eric Holcomb, Joseph Corcoran, 49, convicted in the 1997 killings of his brother and three other people, is scheduled to be put to death by lethal injection before sunrise Wednesday, Dec. 18. (AP Photo/Erin Hooley)

Joseph Corcoran is led to the City-County Lockup on Aug. 26, 1999, in Fort Wayne, Ind., after being sentenced to death in the slayings of four people in July 1997. (Matt Sullivan/The Journal-Gazette via AP)

Police officers walk outside of Indiana State Prison on Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024, in Michigan City, Ind., where, barring last-minute court action or intervention by Gov. Eric Holcomb, Joseph Corcoran, 49, convicted in the 1997 killings of his brother and three other people, is scheduled to be put to death by lethal injection before sunrise Wednesday, Dec. 18. (AP Photo/Erin Hooley)

A sign is posted outside of Indiana State Prison on Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024, in Michigan City, Ind., where, barring last-minute court action or intervention by Gov. Eric Holcomb, Joseph Corcoran, 49, convicted in the 1997 killings of his brother and three other people, is scheduled to be put to death by lethal injection before sunrise Wednesday, Dec. 18. (AP Photo/Erin Hooley)

Indiana State Police officers enter Indiana State Prison on Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024, in Michigan City, Ind., where, barring last-minute court action or intervention by Gov. Eric Holcomb, Joseph Corcoran, 49, convicted in the 1997 killings of his brother and three other people, is scheduled to be put to death by lethal injection before sunrise Wednesday, Dec. 18. (AP Photo/Erin Hooley)

A police officer walks outside of Indiana State Prison on Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024, in Michigan City, Ind., where, barring last-minute court action or intervention by Gov. Eric Holcomb, Joseph Corcoran, 49, convicted in the 1997 killings of his brother and three other people, is scheduled to be put to death by lethal injection before sunrise Wednesday, Dec. 18. (AP Photo/Erin Hooley)

A sign is posted outside of Indiana State Prison on Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024, in Michigan City, Ind., where, barring last-minute court action or intervention by Gov. Eric Holcomb, Joseph Corcoran, 49, convicted in the 1997 killings of his brother and three other people, is scheduled to be put to death by lethal injection before sunrise Wednesday, Dec. 18. (AP Photo/Erin Hooley)

The sun sets behind Indiana State Prison on Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024, in Michigan City, Ind., where, barring last-minute court action or intervention by Gov. Eric Holcomb, Joseph Corcoran, 49, convicted in the 1997 killings of his brother and three other people, is scheduled to be put to death by lethal injection before sunrise Wednesday, Dec. 18. (AP Photo/Erin Hooley)

Police cars are parked outside of Indiana State Prison on Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024, in Michigan City, Ind., where, barring last-minute court action or intervention by Gov. Eric Holcomb, Joseph Corcoran, 49, convicted in the 1997 killings of his brother and three other people, is scheduled to be put to death by lethal injection before sunrise Wednesday, Dec. 18. (AP Photo/Erin Hooley)

This undated photo provided by the Indiana Department of Corrections, shows Joseph Corcoran, who is scheduled to be executed before sunrise on Dec. 18, 2024. (Indiana Department of Corrections via AP)

A guard stands in a tower at Indiana State Prison on Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024, in Michigan City, Ind., where, barring last-minute court action or intervention by Gov. Eric Holcomb, Joseph Corcoran, 49, convicted in the 1997 killings of his brother and three other people, is scheduled to be put to death by lethal injection before sunrise Wednesday, Dec. 18. (AP Photo/Erin Hooley)