WILTON, Iowa (AP) — Every year the U.S. egg industry kills about 350 million male chicks because, while the fuzzy little animals are incredibly cute, they will never lay eggs, so have little monetary value.

That longtime practice is changing, thanks to new technology that enables hatcheries to quickly peer into millions of fertilized eggs and spot male embryos, then grind them up for other uses before they mature into chicks. The system began operating this month in Iowa at the nation's largest chick hatchery, which handles about 387,000 eggs each day.

Click to Gallery

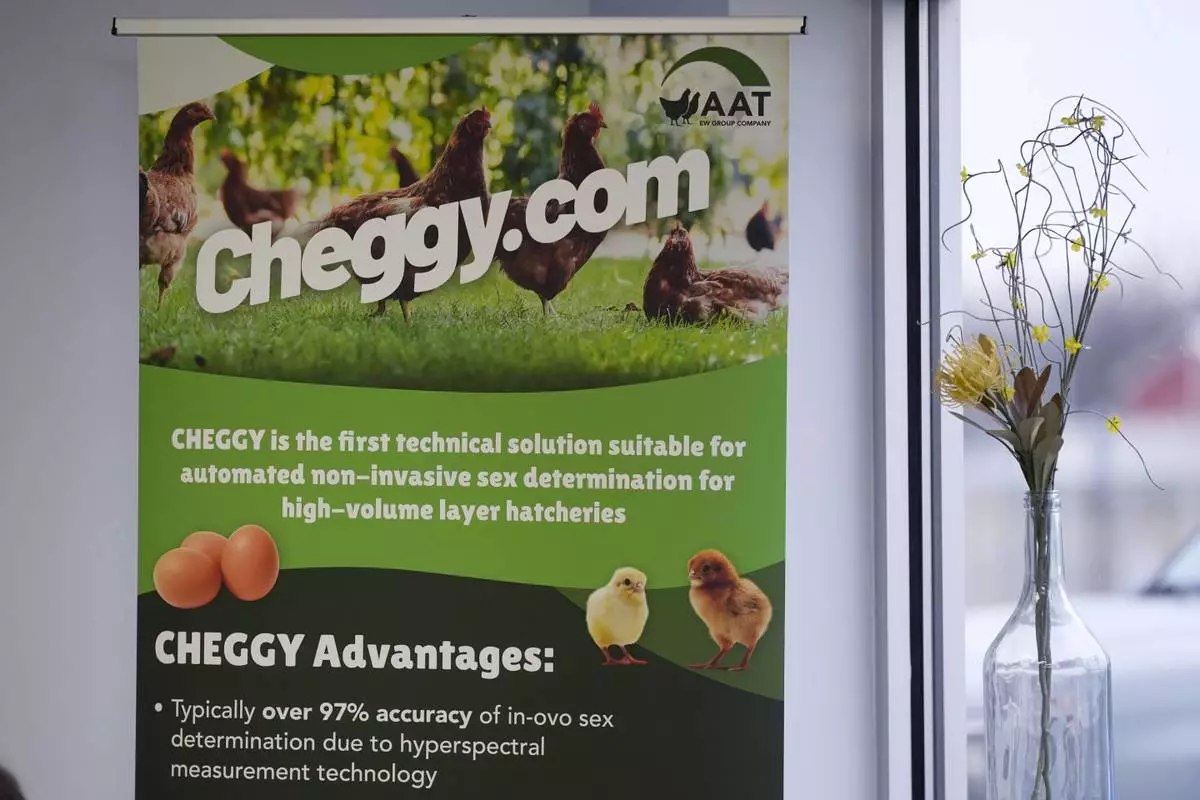

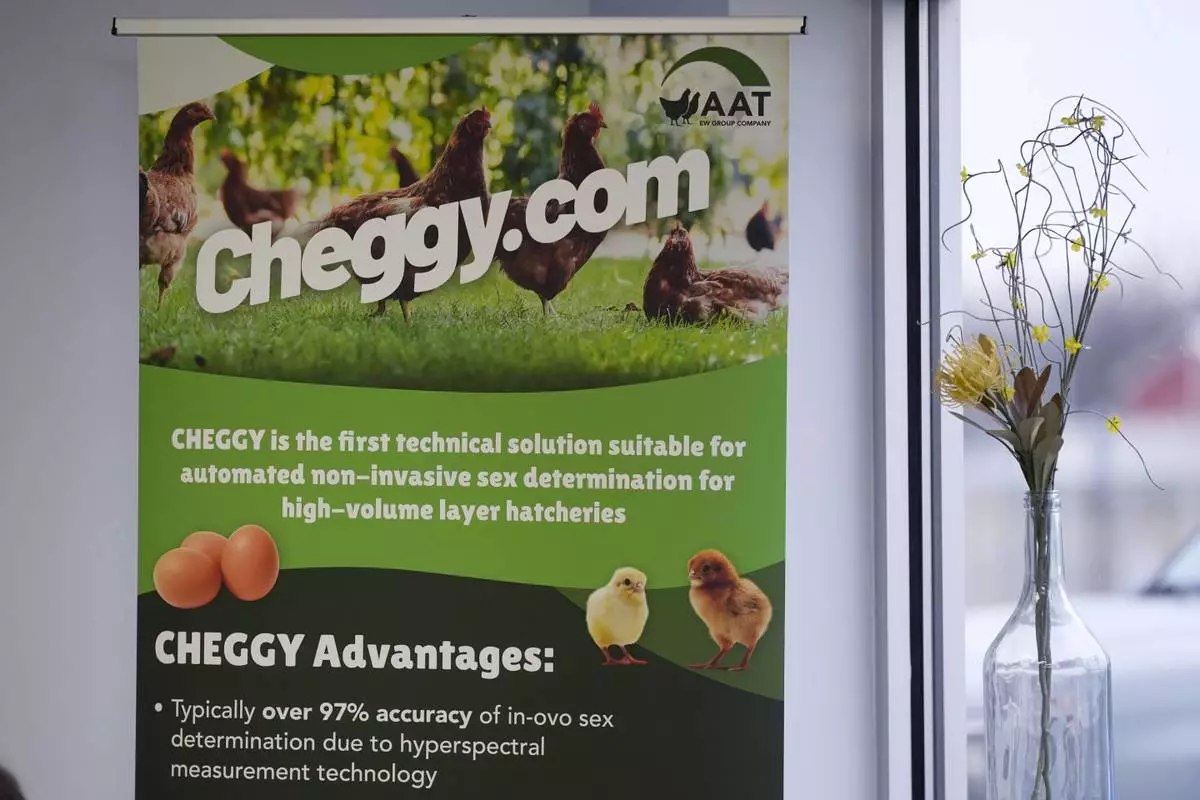

A display board for the CHEGGY machine, an SUV-sized machine that can separate eggs by sex, is displayed before a demonstration at the Hy-Line hatchery, Tuesday, Dec. 10, 2024, in Wilton, Iowa. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)

NestFresh executive vice president Jasen Urena speaks about the CHEGGY machine, an SUV-sized machine that can separate eggs by sex, before a demonstration at the Hy-Line hatchery, Tuesday, Dec. 10, 2024, in Wilton, Iowa. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)

A company sign is seen in a conference room at the Hy-Line hatchery Tuesday, Dec. 10, 2024, in Wilton, Iowa. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)

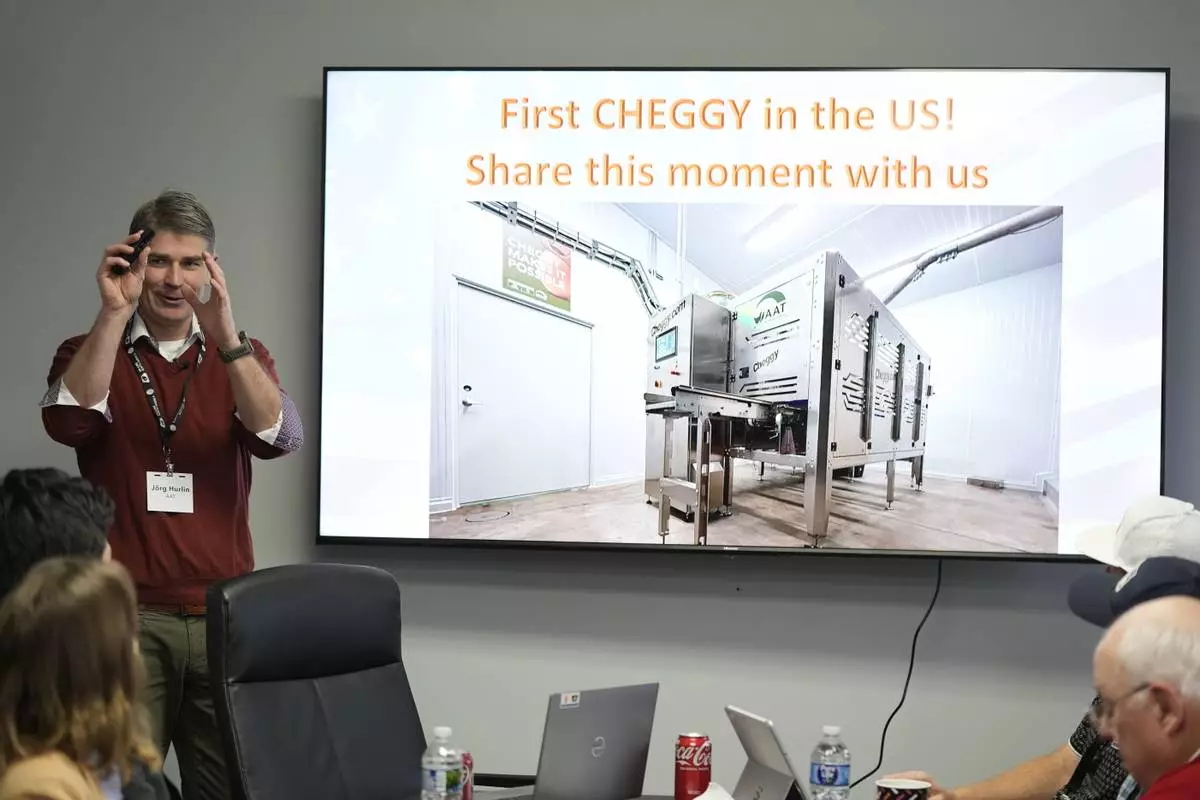

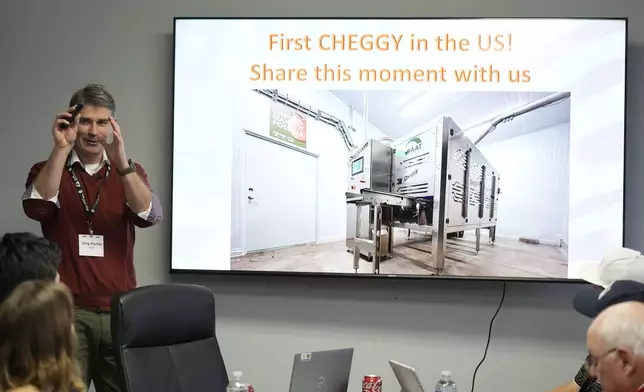

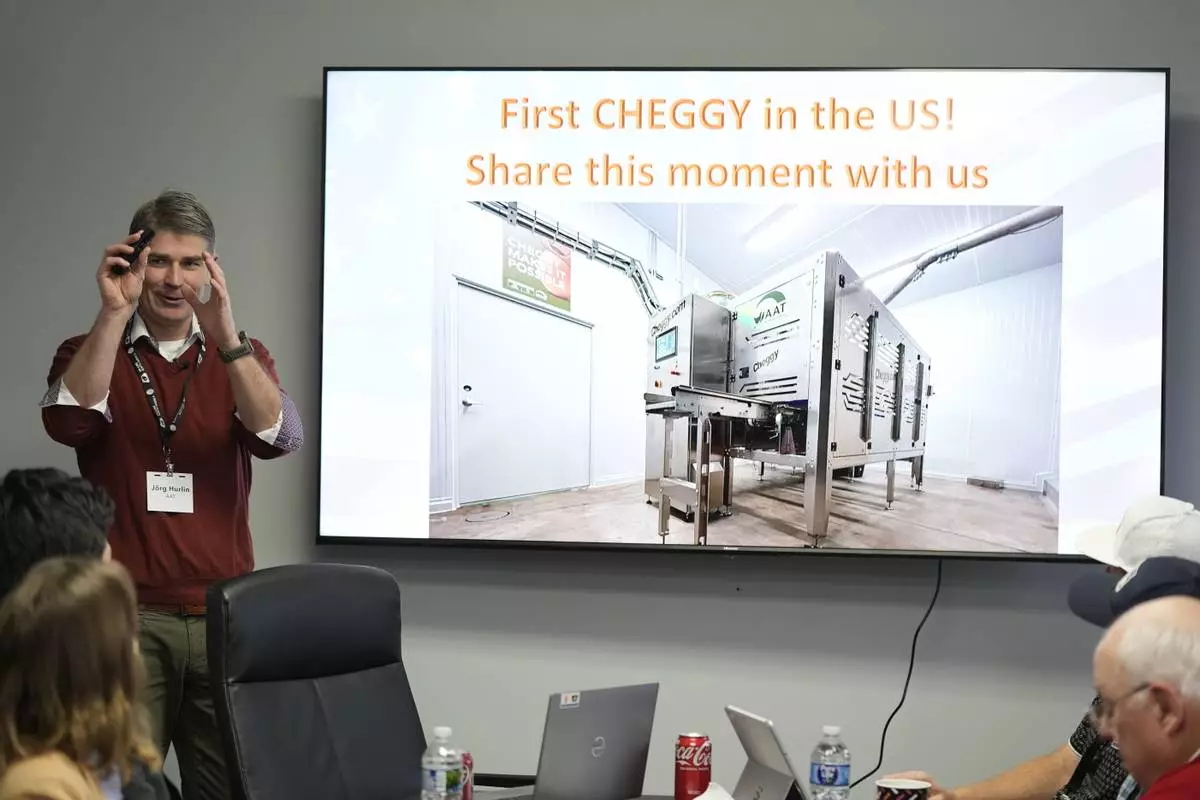

Managing director of Agri Advanced Technologies Jörg Hurlin speaks about the CHEGGY machine, an SUV-sized machine that can separate eggs by sex, before a demonstration at the Hy-Line hatchery, Tuesday, Dec. 10, 2024, in Wilton, Iowa. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)

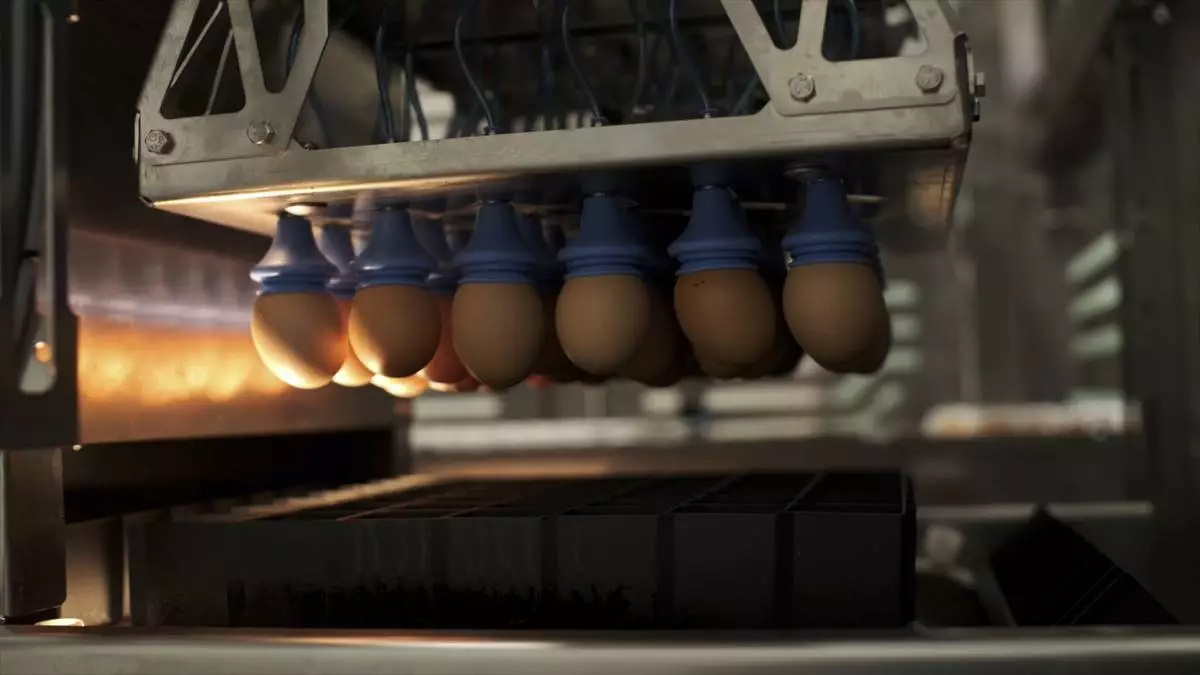

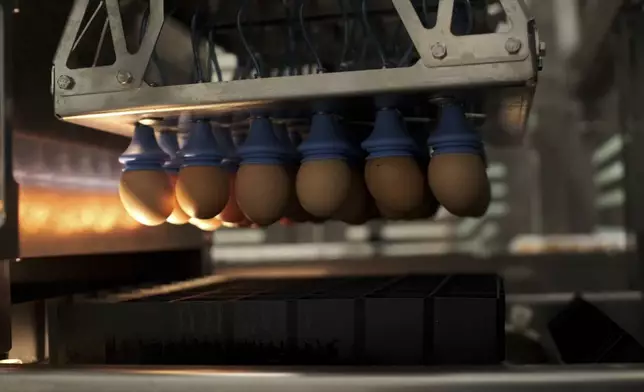

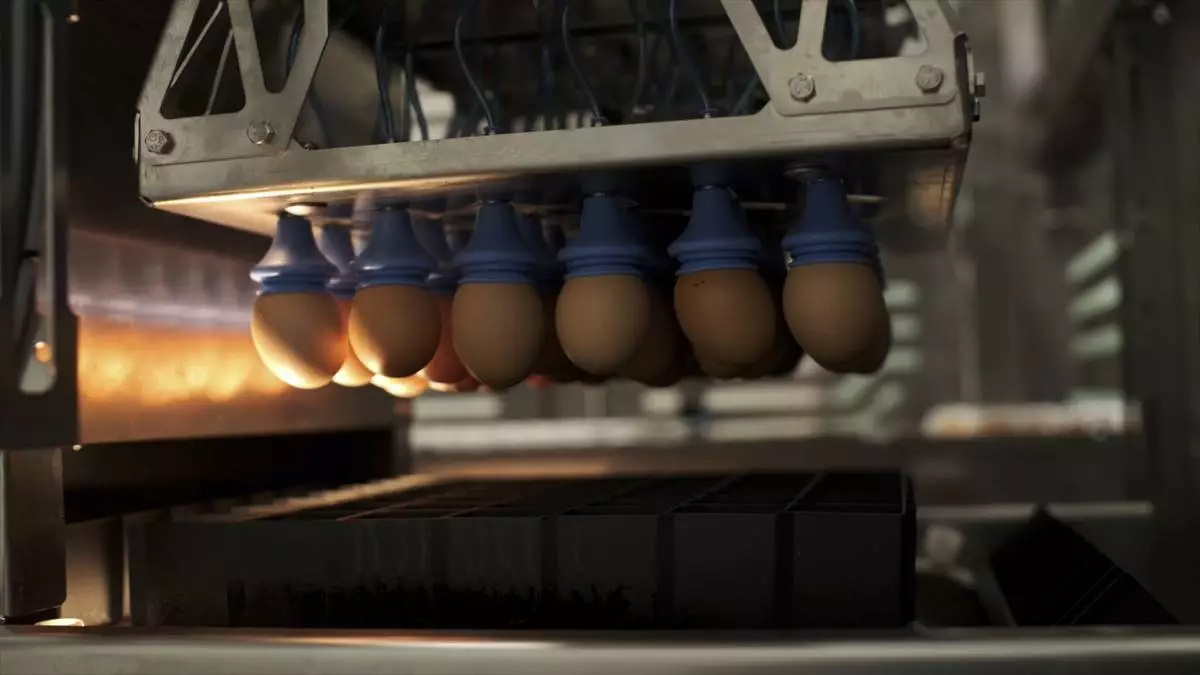

Eggs are lifted from trays and transferred inside a machine that provides a new technique to enable hatcheries to peek into millions of fertilized eggs and spot male embryos, then grind them up for other uses before they mature into chicks, in Wilton, Iowa, Dec. 10, 2024. This is an alternative to the longstanding practice of chick culling where male chicks are killed because they have little monetary value since they do not lay eggs. (Courtesy Tony Reidsma via AP)

A worker guides a tray of chicken eggs into a machine that provides a new technique to enable hatcheries to peek into millions of fertilized eggs and spot male embryos, then grind them up for other uses before they mature into chicks, in Wilton, Iowa, Dec. 10, 2024. This is an alternative to the longstanding practice of chick culling when male chicks are killed because they have little monetary value since they do not lay eggs. (Courtesy Tony Reidsma via AP)

Newly hatched chicks are seen after being sorted in a machine that provides a new technique to enable hatcheries to peek into millions of fertilized eggs and spot male embryos, then grind them up for other uses before they mature into chicks, in Wilton, Iowa, Dec. 10, 2024. This is an alternative to the longstanding practice of chick culling when male chicks are killed because they have little monetary value since they do not lay eggs. (Courtesy Tony Reidsma via AP)

“We now have ethically produced eggs we can really feel good about,” said Jörg Hurlin, managing director of Agri Advanced Technologies, the German company that spent more than a decade developing the SUV-sized machine that can separate eggs by sex.

Even Americans who are careful to buy cage free or free range eggs typically aren't aware that hundreds of millions of male chicks are killed each year, usually when they are only a day old. Most of the animals are culled through a process called maceration that uses whirling blades to nearly instantly kill the baby birds — something that seems horrifying but that the industry has long claimed is the most humane alternative.

“Does the animal suffer? No because it's instantaneous death. But it's not pretty because it's a series of rotating blades,” said Suzanne Millman, a professor at Iowa State University who focuses on animal welfare.

Chick culling is an outgrowth of a poultry industry that for decades has raised one kind of chicken for eggs and another for meat. Egg-laying chickens are too scrawny to profitably be sold for meat, so the male chicks are ground up and used as additives for other products.

It wasn't until European governments began passing laws that outlawed maceration that companies started puzzling out how to determine chicken sex before the chicks can hatch. Several companies can now do that, but unlike most competitors, AAT's machine doesn't need to pierce the shell and instead uses a bright light and sensitive cameras to detect an embryo's sex by noting feather shading. Males are white, and females are dark.

The machine, called Cheggy, can process up to 25,000 eggs an hour, a pace that can accommodate the massive volume seen at hatcheries in the U.S. Besides the Cheggy machine in the small eastern Iowa city of Wilton, an identical system has been installed in Texas, both at hatcheries owned by Hy-Line North America.

The process has one key limitation: It works only on brown eggs because male and female chicks in white eggs have similar-colored feathers.

That's not a huge hindrance in Europe, where most eggs sold at groceries are brown. But in the U.S., white shell eggs make up about 81% of sales, according to the American Egg Board. Brown shell eggs are especially sought by people who buy cage-free, free-range and organic varieties.

Hurlin said he thinks his company will develop a system to tell the sex of embryos in white eggs within five years, and other companies also are working to meet what's expected to be a growing demand.

Eggs from hens that were screened through the new system will supply NestFresh Eggs, a Southern California-based business that distributes organic eggs produced by small operations across the country. The eggs will begin showing up on store shelves in mid-July and NestFresh executive vice president Jasen Urena said his company will begin touting the new chick-friendly process on cartons and with a larger marketing effort.

“It's a huge jump in animal welfare,” Urena said. “We've done so much work over the years on the farms. How do we make the lives of these chickens better? Now we're able to step back and go into the hatching phase.”

Urena said the new system was more expensive but any price increase on store shelves would be minimal.

The animal welfare group Mercy for Animals has tried to draw attention to chick culling for more than a decade in hopes of ending the practice.

Walter Sanchez-Suarez, the group's animal behavior and welfare scientist, said laws in Europe outlawing chick culling and new efforts to change the practice in the U.S. are wonderful developments. However, Sanchez-Suarez sees them as a small step toward a larger goal of ending large-scale animal agriculture and offering alternatives to meat, eggs and dairy.

“Mercy for Animals thinks this is an important step, but poultry producers shouldn't stop there and should try to see all the additional problems that are associated to this type of practice in egg production,” he said. “Look for alternatives that are better for animals themselves and human consumers.”

A display board for the CHEGGY machine, an SUV-sized machine that can separate eggs by sex, is displayed before a demonstration at the Hy-Line hatchery, Tuesday, Dec. 10, 2024, in Wilton, Iowa. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)

NestFresh executive vice president Jasen Urena speaks about the CHEGGY machine, an SUV-sized machine that can separate eggs by sex, before a demonstration at the Hy-Line hatchery, Tuesday, Dec. 10, 2024, in Wilton, Iowa. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)

A company sign is seen in a conference room at the Hy-Line hatchery Tuesday, Dec. 10, 2024, in Wilton, Iowa. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)

Managing director of Agri Advanced Technologies Jörg Hurlin speaks about the CHEGGY machine, an SUV-sized machine that can separate eggs by sex, before a demonstration at the Hy-Line hatchery, Tuesday, Dec. 10, 2024, in Wilton, Iowa. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)

Eggs are lifted from trays and transferred inside a machine that provides a new technique to enable hatcheries to peek into millions of fertilized eggs and spot male embryos, then grind them up for other uses before they mature into chicks, in Wilton, Iowa, Dec. 10, 2024. This is an alternative to the longstanding practice of chick culling where male chicks are killed because they have little monetary value since they do not lay eggs. (Courtesy Tony Reidsma via AP)

A worker guides a tray of chicken eggs into a machine that provides a new technique to enable hatcheries to peek into millions of fertilized eggs and spot male embryos, then grind them up for other uses before they mature into chicks, in Wilton, Iowa, Dec. 10, 2024. This is an alternative to the longstanding practice of chick culling when male chicks are killed because they have little monetary value since they do not lay eggs. (Courtesy Tony Reidsma via AP)

Newly hatched chicks are seen after being sorted in a machine that provides a new technique to enable hatcheries to peek into millions of fertilized eggs and spot male embryos, then grind them up for other uses before they mature into chicks, in Wilton, Iowa, Dec. 10, 2024. This is an alternative to the longstanding practice of chick culling when male chicks are killed because they have little monetary value since they do not lay eggs. (Courtesy Tony Reidsma via AP)

NEW YORK (AP) — The suspect in the killing of UnitedHealthcare’s CEO was whisked back to New York by helicopter Thursday to face new federal charges of murder and stalking, escalating the case after his earlier indictment on state charges.

Luigi Mangione agreed to go return to New York after a morning court appearance in Pennsylvania, where he was arrested last week after five days on the run. He was expected in a Manhattan federal court in the afternoon.

After his Pennsylvania court hearing, Mangione was immediately turned over to at least a dozen New York Police Department officers who were in the courtroom and led him to a plane bound for Long Island. He then was flown to a Manhattan heliport, where he was walked slowly up a pier by officers with assault rifles.

The federal complaint unsealed Thursday charges him with two counts of stalking and one count each of murder through use of a firearm and a firearms offense. One of the federal charges, murder by firearm, could bring the possibility of the death penalty if he is convicted. Federal prosecutors have not said whether they will pursue the such a punishment.

Mangione could face life in prison without parole if convicted on the New York state charges, which include murder as an act of terrorism.

In Pennsylvania, Blair County District Attorney Pete Weeks said Thursday that he wanted to turn Mangione over to New York authorities as soon as possible.

“He is now in their custody. He will go forth with New York to await trial or prosecution for his homicide and related charges in New York," Weeks said.

The 26-year-old Ivy League graduate is accused of ambushing and shooting Brian Thompson on Dec. 4 outside a Manhattan hotel where the head of the United States’ largest medical insurance company was walking to an investor conference.

Authorities have said Mangione was carrying the gun used to kill Thompson, a passport, fake IDs and about $10,000 when he was arrested while eating breakfast on Dec. 9 at a McDonald’s in Altoona, Pennsylvania.

Mangione, who initially fought attempts to extradite him, made two brief court appearances Thursday, first waiving a preliminary hearing on forgery and firearms charges before agreeing to be sent back to New York.

Investigators believe Mangione was motivated by anger toward the U.S. health care system and corporate greed. But he was never a UnitedHealthcare client, according to the insurer.

According to the federal complaint, a notebook Mangione was carrying when he was arrested included several handwritten pages expressing hostility toward the health insurance industry and wealthy executives in particular.

An August entry said that “the target is insurance” because “it checks every box,” according to the filing. An entry in October “describes an intent to ‘wack’ the CEO of one of the insurance companies at its investor conference,” the document said.

The killing ignited an outpouring of stories about resentment toward U.S. health insurance companies while also shaking corporate America after some social media users called the shooting payback.

Video showed a masked gunman shooting Thompson, 50, from behind and then firing several more shots. The suspect eluded police despite authorities widely circulating photos of his unmasked face until Mangione was captured in Altoona, about 277 miles (446 kilometers) west of New York.

Mangione, a computer science graduate from a prominent Maryland family, was carrying a handwritten letter that called health insurance companies “parasitic” and complained about corporate greed, according to a law enforcement bulletin obtained by The Associated Press last week.

One of his lawyers has cautioned the public against prejudging the case.

Mangione repeatedly posted on social media about how spinal surgery last year had eased his chronic back pain, encouraging people with similar conditions to speak up for themselves if told they just had to live with it.

In a Reddit post in late April, he advised someone with a back problem to seek additional opinions from surgeons and, if necessary, say the pain made it impossible to work.

“We live in a capitalist society,” Mangione wrote. “I’ve found that the medical industry responds to these key words far more urgently than you describing unbearable pain and how it’s impacting your quality of life.”

He apparently cut himself off from his family and close friends in recent months. His family reported him missing in San Francisco in November. His relatives have said in a statement that they were “shocked and devastated” by his arrest.

Thompson, who grew up on a farm in Iowa, was trained as an accountant. A married father of two high-schoolers, he had worked at the giant UnitedHealth Group for 20 years and became CEO of its insurance arm in 2021.

Sisak and Neumeister reported from New York. Associated Press writers Mike Rubinkam in Allentown, Pennsylvania; and John Seewer in Toledo, Ohio; contributed.

Luigi Nicholas Mangione leaves at Blair County Courthouse in Hollidaysburg, Pa., Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Gene J. Puskar, Pool)

Luigi Nicholas Mangione leaves at Blair County Courthouse in Hollidaysburg, Pa., Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Gene J. Puskar, Pool)

Luigi Nicholas Mangione leaves at Blair County Courthouse in Hollidaysburg, Pa., Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Gene J. Puskar, Pool)

Luigi Nicholas Mangione leaves at Blair County Courthouse in Hollidaysburg, Pa., Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Gene J. Puskar, Pool)

Luigi Nicholas Mangione leaves at Blair County Courthouse in Hollidaysburg, Pa., Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Gene J. Puskar, Pool)

Luigi Nicholas Mangione leaves at Blair County Courthouse in Hollidaysburg, Pa., Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Gene J. Puskar, Pool)

Luigi Nicholas Mangione arrives at Blair County Courthouse in Hollidaysburg, Pa., Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Gene J. Puskar, Pool)

Luigi Nicholas Mangione is escorted into Blair County Courthouse, Tuesday, Dec. 10, 2024, in Hollidaysburg, Pa. (AP Photo/Gary M. Baranec)

This combo image release by Pennsylvania State Police shows Luigi Mangione, a suspect in the fatal shooting of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson, at a McDonald's in Altoona, Pa., Monday, Dec. 9, 2024. (Pennsylvania State Police via AP)

Suspect Luigi Mangione is taken into the Blair County Courthouse on Tuesday, Dec. 10, 2024, in Hollidaysburg, Pa. (Benjamin B. Braun/Pittsburgh Post-Gazette via AP)