California officials have declared a state of emergency over the spread of bird flu, which is tearing through dairy cows in that state and causing sporadic illnesses in people in the U.S.

That raises new questions about the virus, which has spread for years in wild birds, commercial poultry and many mammal species.

The virus, also known as Type A H5N1, was detected for the first time in U.S. dairy cattle in March. Since then, bird flu has been confirmed in at least 866 herds in 16 states.

More than 60 people in eight states have been infected, with mostly mild illnesses, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One person in Louisiana has been hospitalized with the nation's first known severe illness caused by the virus, health officials said this week.

Here’s what you need to know.

Gov. Gavin Newsom said he declared the state of emergency to better position state staff and supplies to respond to the outbreak.

California has been looking for bird flu in large milk tanks during processing. And they have found the virus it at least 650 herds, representing about three-quarters of all affected U.S. dairy herds.

The virus was recently detected in Southern California dairy farms after being found in the state’s Central Valley since August.

“This proclamation is a targeted action to ensure government agencies have the resources and flexibility they need to respond quickly to this outbreak,” Newsom said in a statement.

Officials with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stressed again this week that the virus poses low risk to the general public.

Importantly, there are no reports of person-to-person transmission and no signs that the virus has changed to spread more easily among humans.

In general, flu experts agreed with that assessment, saying it’s too soon to tell what trajectory the outbreak could take.

“The entirely unsatisfactory answer is going to be: I don’t think we know yet,” said Richard Webby, an influenza expert at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

But virus experts are wary because flu viruses are constantly mutating and small genetic changes could change the outlook.

This week, health officials confirmed the first known case of severe illness in the U.S. All previous the previous U.S. cases — there have been about 60 — were generally mild.

The patient in Louisiana, who is older than 65 and had underlying medical problems, is in critical condition. Few details have been released, but officials said the person developed severe respiratory symptoms after exposure to a backyard flock of sick birds.

That makes it the first confirmed U.S. infection tied to backyard birds, the CDC said.

Tests showed that the strain that caused the person's illness is one found in wild birds, but not in cattle. Last month, health officials in Canada reported that a teen in British Columbia was hospitalized with a severe case of bird flu, also with the virus strain found in wild birds.

Previous infections in the U.S. have been almost all in farmworkers with direct exposure to infected dairy cattle or poultry. In two cases — and adult in Missouri and a child in California — health officials have not determined how they caught it.

It's possible that as more people become infected, more severe illnesses will occur, said Angela Rasmussen, a virus expert at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada.

Worldwide, nearly 1,000 cases of illnesses caused by H5N1 have been reported since 2003, and more than half of people infected have died, according to the World Health Organization.

“I assume that every H5N1 virus has the potential to be very severe and deadly,” Rasmussen said.

People who have contact with dairy cows or commercial poultry or with backyard birds are at higher risk and should use precautions including respiratory and eye protection and gloves, CDC and other experts said.

“If birds are beginning to appear ill or die, they should very careful about how they handle those animals,” said Michael Osterholm, a public health disease expert at the University of Minnesota.

The CDC has paid for flu shots to protect farmworkers against seasonal flu — and against the risk that the workers could become infected with two flu types at the same time, potentially allowing the bird flu virus to mutate and become more dangerous. The government also said that farmworkers who come in close contact with infected animals should be tested and offered antiviral drugs even if they show no symptoms.

In addition to direct contact with farm animals and wild birds, the H5N1 virus can be spread in raw milk. Pasteurized milk is safe to drink, because the heat treatment kills the virus, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

But high levels of the virus have been found in unpasteurized milk. And raw milk sold in stores in California was recalled in recent weeks after the virus was detected at farms and in the products.

In Los Angeles, county officials reported that two indoor cats that were fed the recalled raw milk died from bird flu infections. Officials were investigating additional reports of sick cats.

Health officials urge people to avoid drinking raw milk, which can spread a host of germs in addition to bird flu.

The U.S. Agriculture Department has stepped up testing of raw milk across the country to help detect and contain the outbreak. A federal order issued this month requires testing, which began this week in 13 states.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

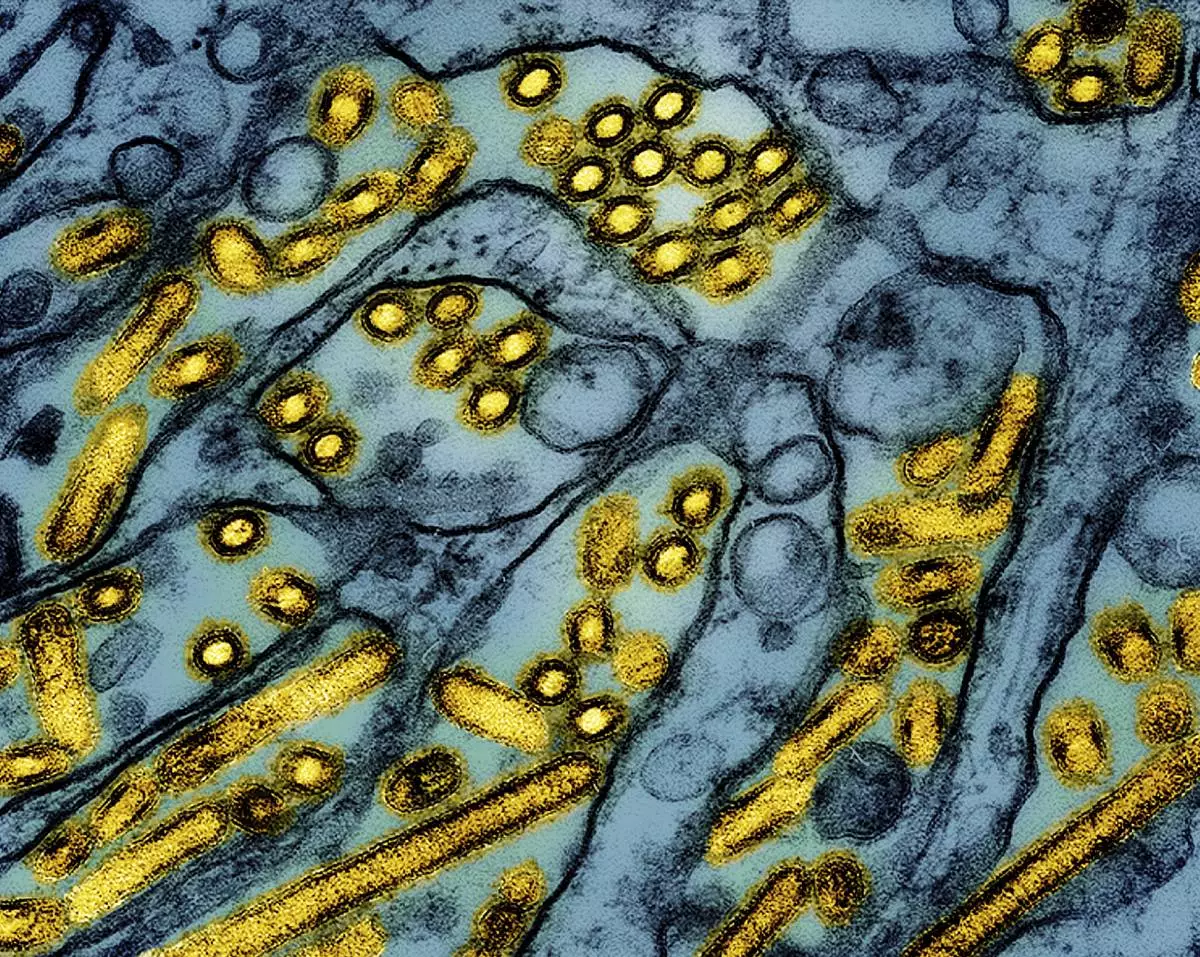

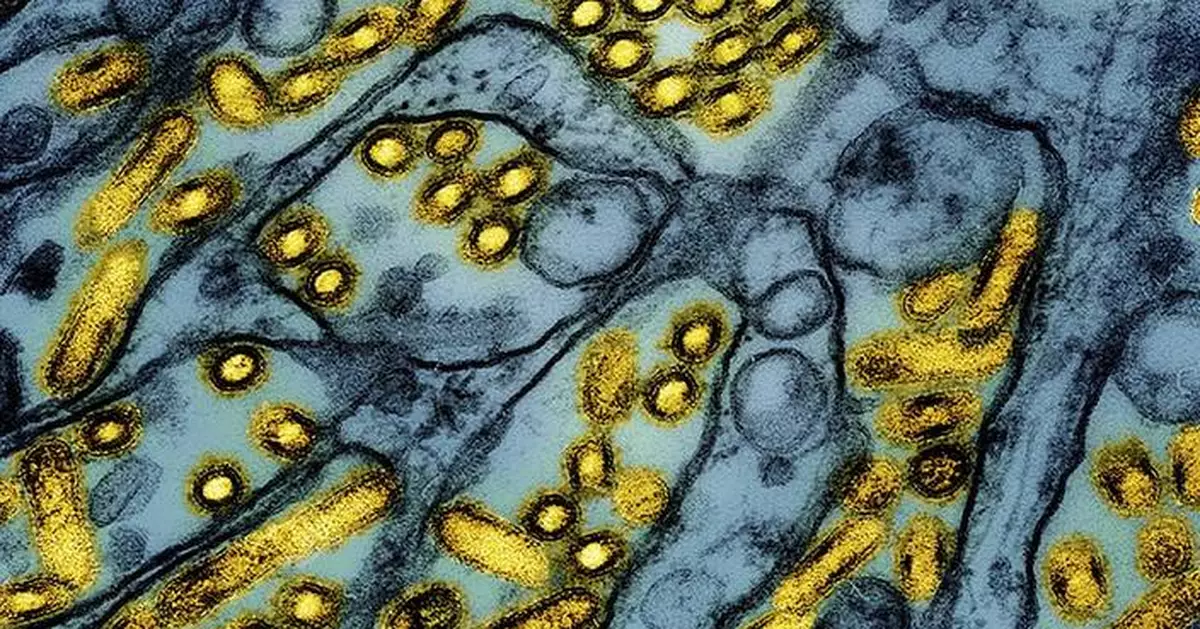

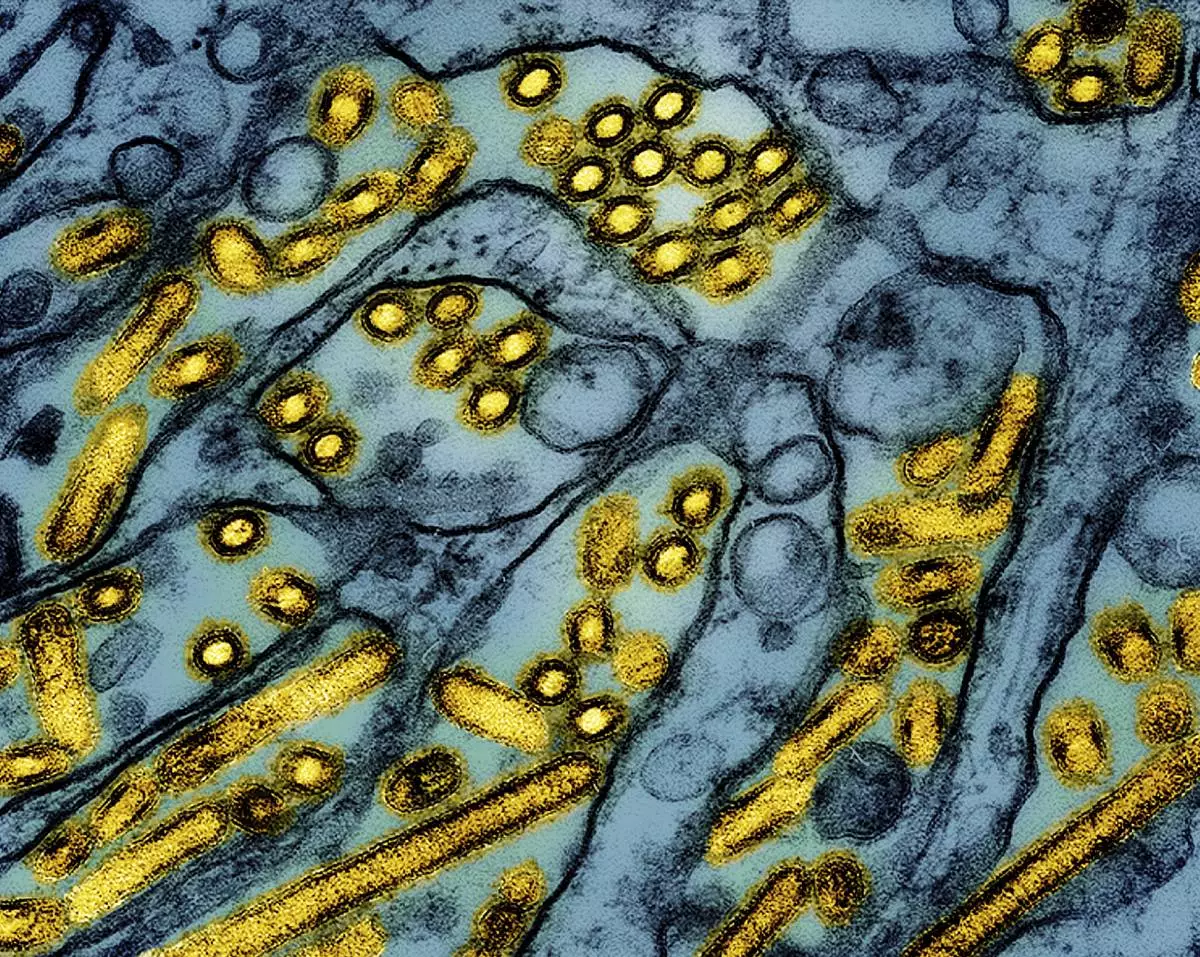

FILE -This colorized electron microscope image released by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases on March 26, 2024, shows avian influenza A H5N1 virus particles (yellow), grown in Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) epithelial cells (blue). (CDC/NIAID via AP, File)

MAMOUDZOU, Mayotte (AP) — French President Emmanuel Macron arrived Thursday in the Indian Ocean island of Mayotte to survey Cyclone Chido’s destruction and was immediately confronted with a first-hand account of devastation across the French territory.

“Mayotte is demolished,” Assane Haloi, a security agent, told Macron after he stepped off the plane.

Macron had been moving along in a line of people greeting him when Haloi grasped his hand and spoke for a minute about the harrowing conditions the islands faced without bare essentials since Saturday when the strongest cyclone in nearly a century ripped through the French territory off the coast of Africa.

“We are without water, without electricity, there is nowhere to go because everything is demolished,” she said. “We can’t even shelter, we are all wet with our children covering ourselves with whatever we have so that we can sleep.”

At least 31 people have died and more than 2,000 people were injured, more than 200 critically, French authorities said. But it’s feared hundreds or even thousands of people have died.

Macron arrived shortly after The Associated Press and other journalists from outside were able to reach Mayotte to provide accounts from survivors of the horror over the weekend when winds howled above 220 kph (136 mph) and peeled the roofs and walls from homes that collapsed around the people inside.

In the shantytown of Kaweni on the outskirts of the capital Mamoudzou, a swath of hillside homes was reduced to scraps of corrugated metal, plastic, piles of bedding and clothing, and pieces of timber marking the frame where homes once stood.

“Those of us who are here are still in shock, but God let us live,” Nassirou Hamidouni said as he dug in the rubble of his former home. “We are sad. We can’t sleep because of all of the houses that have been destroyed.”

Macron took a helicopter tour of the damage and then met with patients and staff at a hospital, where a woman who works in the psychological unit became emotional as she described staff becoming exhausted and unable to care for patients.

“Help the hospital staff, help the hospital,” the woman, whose name was not known, pleaded. “Everyone from top to bottom is wiped out.”

Macron, who was wearing a traditional red, black and gold Mayotte scarf over his white dress shirt and tie, put his hand on her shoulder as she wiped away tears.

He sought to reassure people that tons of food, medical aid and additional rescuers had arrived with him and more help was on its way in the form of water, doctors and a field hospital to be set up Friday. A navy ship brought 180 tons of aid and equipment, the French military said.

But the visit took a testy turn when Macron was criticized for being out of touch about what was happening on the ground by a man who said they had gone six days in Ouangani without water or a visit from rescue services.

The president said it took the military four days to clear the roads and get a plan in place to deliver aid.

"If you want to continue shouting to get airtime,” Macron said as he was cut off, by the man saying he didn't intend to shout. “If you are interested in my response, if not I will walk away.”

Macron said about 50% of the electricity network and water system would be repaired by Friday but it could take several weeks to reach more remote areas.

Residents have expressed anguish at not knowing if loved ones were dead or missing, partly because of the hasty burials required under Muslim practice to lay the dead to rest within 24 hours.

“We’re dealing with open-air mass graves," said Estelle Youssoufa, who represents Mayotte in the French parliament. "There are no rescuers, no one has come to recover the buried bodies.”

Macron acknowledged that many who died haven’t been reported. He said phone services will be repaired “in the coming days” so that people can report their missing loved ones.

Mayotte, with a population of 320,000 residents and an estimated 100,000 additional migrants, is France’s poorest territory.

It is part an archipelago located between mainland Africa’s east coast and northern Madagascar that had been a French colony. Mayotte voted to remain part of France in a 1974 referendum as the rest of the islands became the independent nation of Comoros

The cyclone devastated entire neighborhoods as many people ignored warnings, thinking the storm wouldn’t be so extreme.

Signs of the disaster and its impact were everywhere.

Streets remained swamped in puddles. Throngs of motorbikes and cars lined up at a gas station still in service.

Bright clothing was hung to dry on the wooden frames of homes and along the railings of a footbridge over a debris-strewn stream in the Kaweni slum.

Families sprawled out on blankets at a school where 500 people were taking shelter. Women washed clothing in buckets of water as children played with the pieces of a giant chessboard.

Alibouna Haithouna, a displaced mother of four, was with her own mother who had been forced to leave a hospital after her son died there.

“There was a tragedy. We lost my brother. We are here,” Haithouna said. “My brother’s body, we haven’t been able to get it from the hospital because there is a lot of paperwork to do and in addition to that you have to pay to recover the body.”

Macron waded into a crowd of people waiting for him in Kaweni, kissing children and hugging residents who spoke of their hardship. He said he had witnessed emotion and acknowledged some of the anger he faced but said he was impressed with peoples' resilience.

After a woman described how her home almost collapsed on her children, Macron compared recovery efforts to those needed to reconstruct the recently reopened Notre Dame Cathedral after a disastrous fire.

“If we were able to rebuild our cathedral in five years, it would be a tragedy if we weren’t able to rebuild Mayotte," he said.

Corbet reported from Paris. Associated Press journalist Masha Macpherson in Paris and Brian Melley in London contributed.

Mohamed Ankidine, 28, third left, with feet injuries, Saindou Dahabou who suffers from diabetes, and Alibouna Haithouna, 33, find refuge at the Lycée des Lumières after losing their homes, in Mamoudzou, Mayotte, Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

Workers start the process of reconstruction, in Mamoudzou, Mayotte, Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

Women wash clothes after a short rain filled their pots with water, at the Lycée des Lumières where they found shelter after losing their homes, in Mamoudzou, Mayotte, Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024 . (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

A child plays at the Lycée des Lumières where he found shelter, in Mamoudzou, Mayotte, on Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

People interact by an outdoor chess board, after finding refuge at the Lycée des Lumières after losing their homes, in Mamoudzou, Mayotte, Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

A French officer directs traffic for essential vehicles, in Mamoudzou, Mayotte, Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

People walk along partially flooded roads, in Mamoudzou, Mayotte, Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

A child sleeps at the Lycée des Lumières where he found refuge, Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024 in Mamoudzou, Mayotte, (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

People walk past debris in the Kaweni slum Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024, on the outskirts of Mamoudzou, in the French Indian Ocean island of Mayotte, after Cyclone Chido. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

People walk past debris in the Kaweni slum Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024, on the outskirts of Mamoudzou, in the French Indian Ocean island of Mayotte, after Cyclone Chido. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

A woman carrying her belongings walks past debris after Cyclone Chido in the Kaweni slum Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024, on the outskirts of Mamoudzou, in the French Indian Ocean island of Mayotte. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

Damage is seen in the Kaweni slum Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024, on the outskirts of Mamoudzou, in the French Indian Ocean island of Mayotte, after Cyclone Chido. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

People get water from a well in the lower part of the Kaweni slum where they used to have tap water, on the outskirts of Mamoudzou, in the French Indian Ocean island of Mayotte Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024, after Cyclone Chido. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

Cleared debris after Cyclone Chido are seen in the Kaweni slum on the outskirts of Mamoudzou, in the French Indian Ocean island of Mayotte, Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

A man starts rebuilding his shack in the Kaweni slum on the outskirts of Mamoudzou, in the French Indian Ocean island of Mayotte, Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024, after Cyclone Chido. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

People get water from a well in the lower part of the Kaweni slum where they used to have tap water, on the outskirts of Mamoudzou, in the French Indian Ocean island of Mayotte Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024, after Cyclone Chido. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

Nassirou Hamidouni, 28, father of five, stands amongst the debris of the neighboring destroyed home in the slum of Kaweni on the outskirts of Mamoudzou, in the French Indian Ocean island of Mayotte Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024, after Cyclone Chido. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

Debris litters a stream in the Kaweni slum in the French Indian Ocean island of Mayotte, Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024, after Cyclone Chido.. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant))

People queue for gas in Mamoudzou, in the French Indian Ocean island of Mayotte, Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024, after Cyclone Chido. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

People queue for gas in Mamoudzou, in the French Indian Ocean island of Mayotte, Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024, after Cyclone Chido. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

Women wash clothes in a stream in the Kaweni slum on the outskirts of Mamoudzou in the French Indian Ocean island of Mayotte, Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024, after Cyclone Chido. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

A man stands on his roof in the Kaweni slum on the outskirts of Mamoudzou in the French Indian Ocean island of Mayotte, Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024, after Cyclone Chido. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

A boy sits in his destroyed home in the Kaweni slum on the outskirts of Mamoudzou in the French Indian Ocean island of Mayotte, Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024, after Cyclone Chido. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

A boy stands amidst debris in the Kaweni slum on the outskirts of Mamoudzou in the French Indian Ocean island of Mayotte, Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024, after Cyclone Chido. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

People queue for gas in Mamoudzou in the French Indian Ocean island of Mayotte, Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024, after Cyclone Chido. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

A young girl walks in the Kaweni slum on the outskirts of Mamoudzou, in the French Indian Ocean island of Mayotte, Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024, after Cyclone Chido. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

A young girl walks in the Kaweni slum on the outskirts of Mamoudzou, in the French Indian Ocean island of Mayotte, Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024, after Cyclone Chido. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)

Women rest on a footbridge over a stream filled with debris in the Kaweni slum in the French Indian Ocean island of Mayotte, Thursday, Dec. 19, 2024, after Cyclone Chido. (AP Photo/Adrienne Surprenant)