KURUKKAL MADAM, Sri Lanka (AP) — Pulled from the mud as an infant after the devastating Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004, and reunited with his parents following an emotional court battle, the boy once known as “Baby 81” is now a 20-year-old dreaming of higher education.

Jayarasa Abilash's story symbolized that of the families torn apart by one of the worst natural calamities in modern history, but it also offered hope. More than 35,000 people in Sri Lanka were killed, with others missing.

Click to Gallery

FILE - Jenita Jayarasa, left, the mother claimant of the infant dubbed "Baby 81" holds the child and father claimant Murugupillai Jayarasa, center, shouts as a doctor, center, tries to prevent them from taking the infant, inside a ward at a hospital in Kalmunai, about 210 kilometers (131 miles) east of Colombo, Sri Lanka, Wednesday, Feb. 2, 2005. (AP Photo/Rafiq Maqbool, File)

FILE - Jayarasa Abilash, popularly known as 'Baby 81", naps in the arms of his mother Jenita, as his father, Murugupillai, helps make him comfortable during a photo opportunity in New York, Wednesday, March 2, 2005. (AP Photo/Mary Altaffer, File)

FILE - Jenita Jayarasa, left, the mother claimant of the infant dubbed "Baby 81" holds the child and father claimant Murugupillai Jayarasa, center, shouts as a doctor, center, tries to prevent them from taking the infant, inside a ward at a hospital in Kalmunai, about 210 kilometers (131 miles) east of Colombo, Sri Lanka, Wednesday, Feb. 2, 2005. (AP Photo/Rafiq Maqbool, File)

FILE- A Sri Lankan policeman guards the tsunami survivor infant dubbed "Baby 81" inside a ward as people watch from outside at a hospital in Kalmunai, about 210 kilometers (131 miles) east of Colombo, Sri Lanka, Feb. 3, 2005. (AP Photo/Rafiq Maqbool, File)

Jayarasa Abilash, known as Baby 81 after he was swept away by the 2004 Indian ocean tsunami, smiles as he speaks to Associated Press at his residence in Kurukkalmadam, Sri Lanka, Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

Floral tributes sit at a monument for the victims of 2004 Indian ocean tsunami at the residence of Jayarasa Abilash known as Baby 81 after he was swept away by the 2004 Indian ocean tsunami in Kurukkalmadam, Sri Lanka, Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

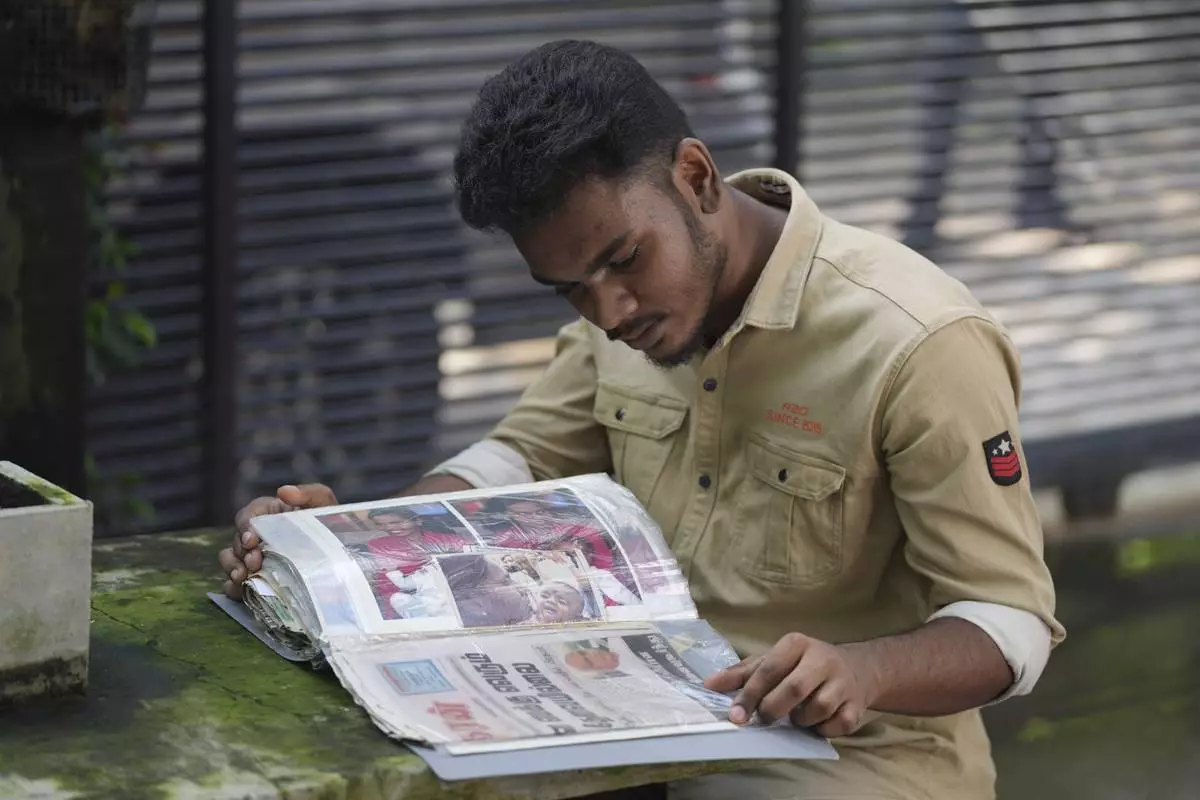

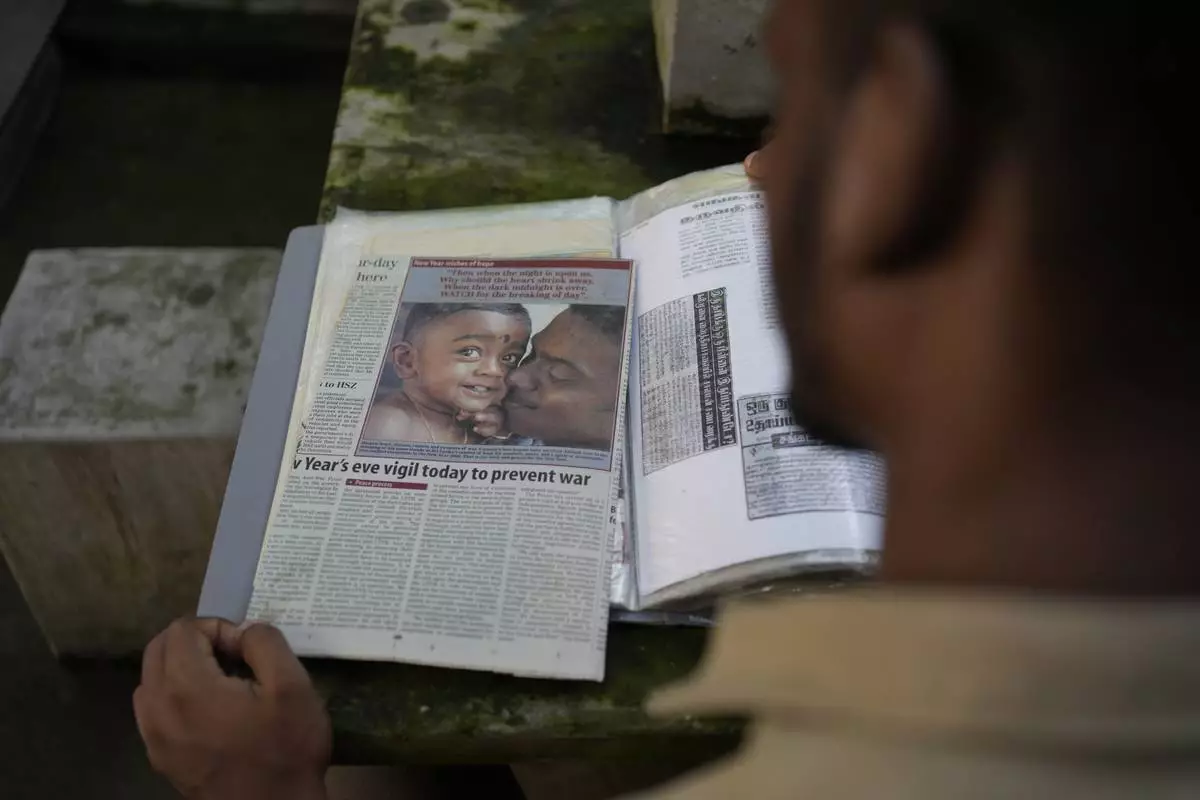

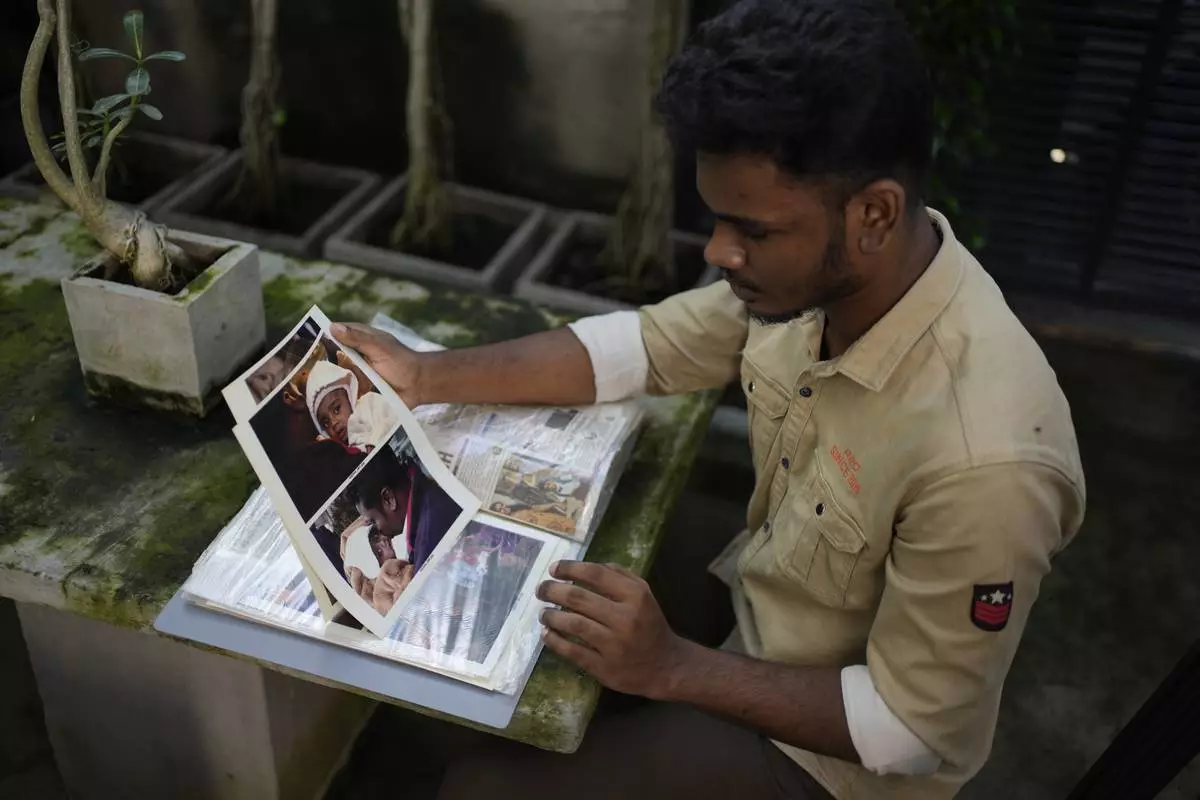

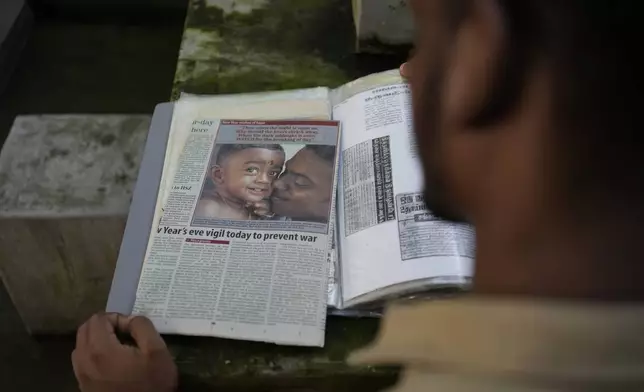

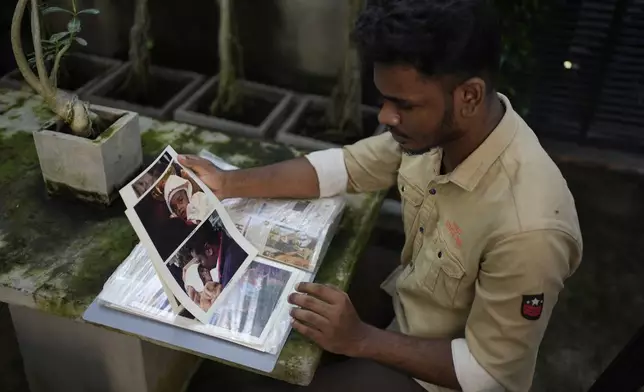

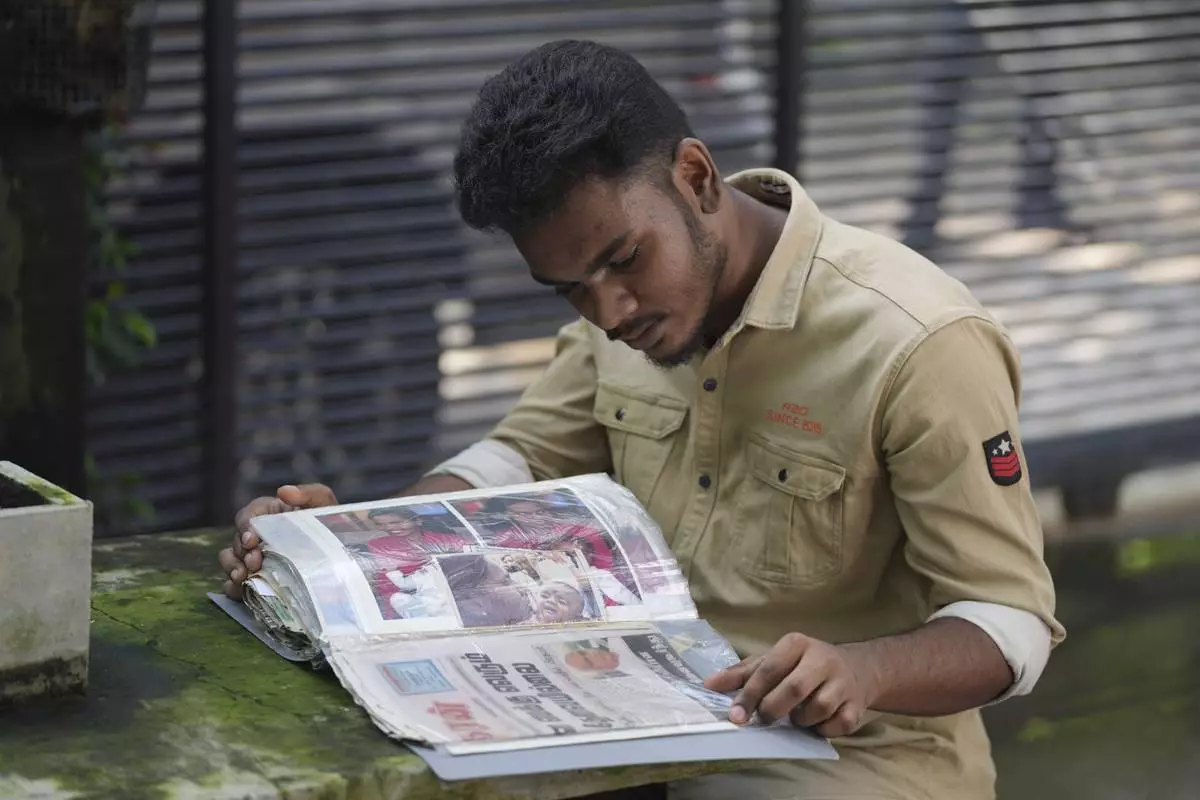

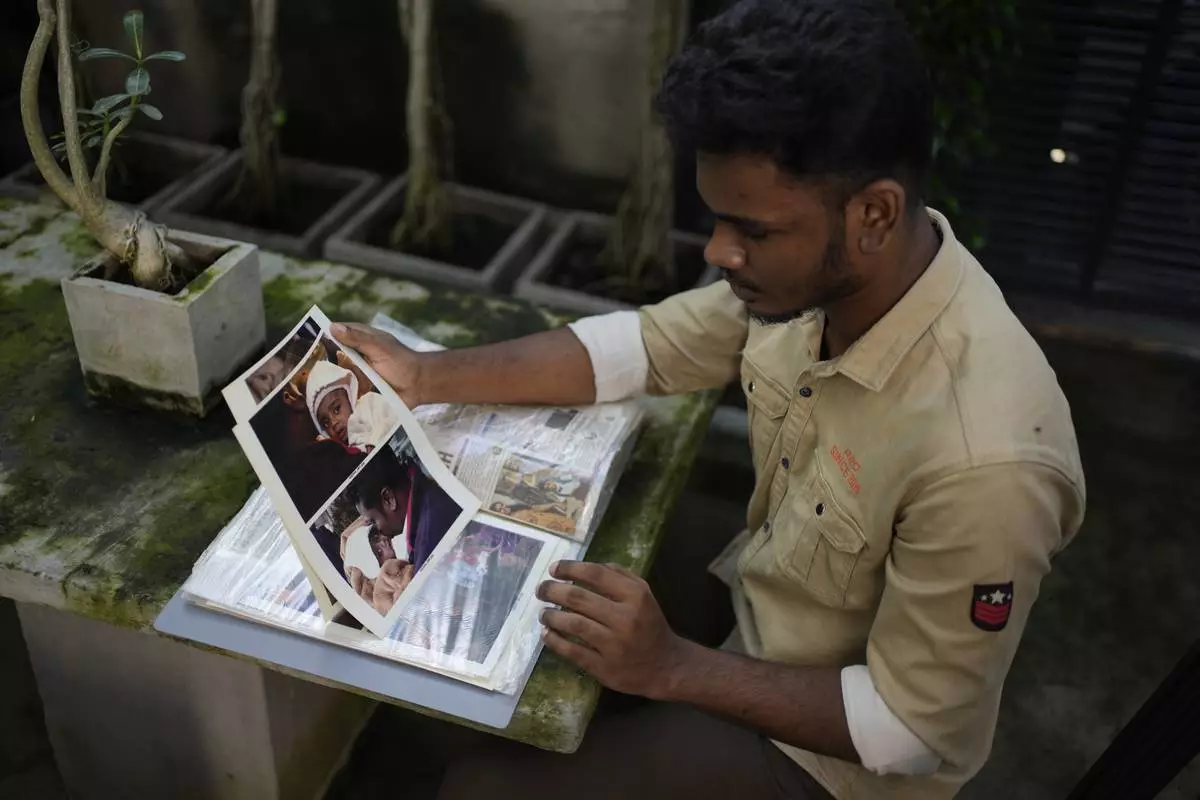

Jayarasa Abilash, known as Baby 81 after he was swept away by the 2004 Indian ocean tsunami, goes through his photo album at his residence in Kurukkalmadam, Sri Lanka, Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

People ride past the surroundings of Jayarasa Abilash, known as Baby 81 after he was swept away by the 2004 Indian ocean tsunami, in Kalmunai, Sri Lanka, Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

Jayarasa Abilash, known as Baby 81 after he was swept away by the 2004 Indian ocean tsunami, goes through his photo album at his residence in Kurukkalmadam, Sri Lanka, Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

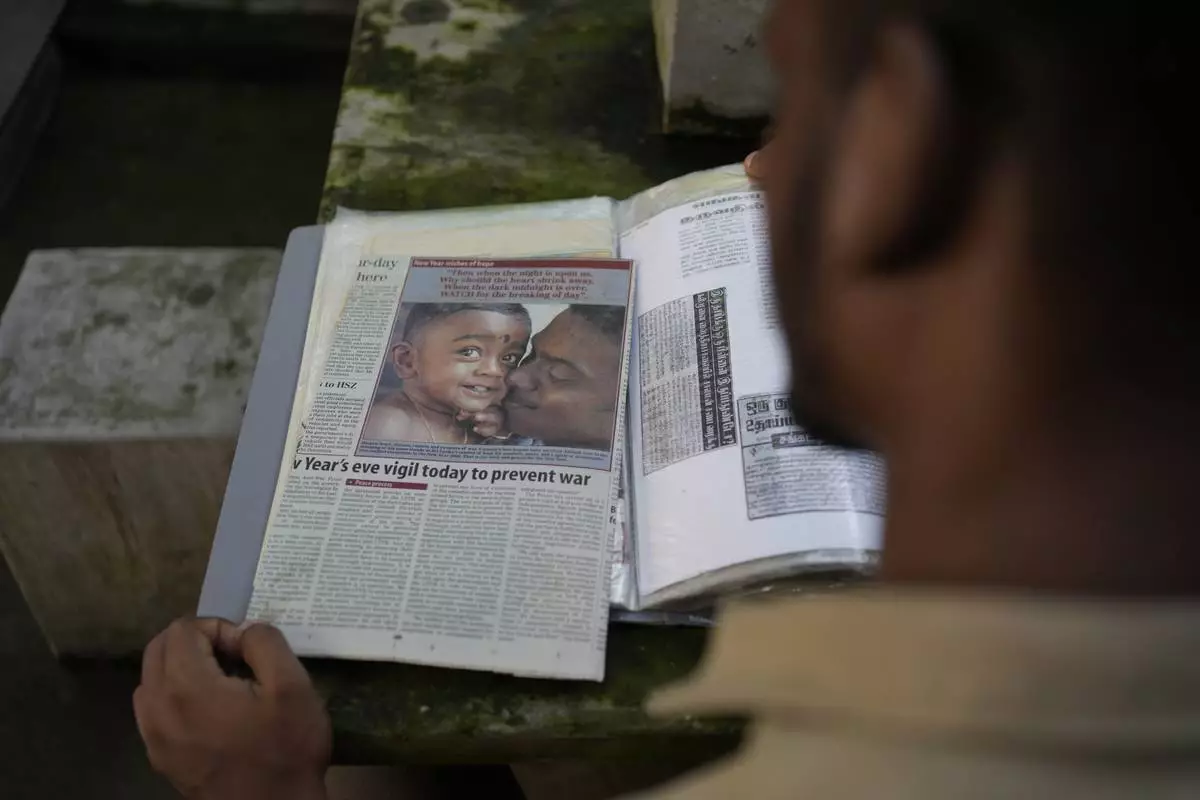

Jayarasa Abilash, known as Baby 81 after he was swept away by the 2004 Indian ocean tsunami goes through his photo album at his residence in Kurukkalmadam, Sri Lanka, Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

Jayarasa Abilash, left, known as Baby 81 after he was swept away by the 2004 Indian ocean tsunami stands in front of a monument built in memory of tsunami victims out side his residence with his father Murugupillai in Kurukkalmadam, Sri Lanka, Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

Jayarasa Abilash, known as Baby 81 after he was swept away by the 2004 Indian ocean tsunami, stands in front of a monument built in memory of tsunami victims outside his residence with his father Murugupillai in Kurukkalmadam, Sri Lanka, Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

Jayarasa Abilash, right, known as Baby 81 after he was swept away by the 2004 Indian ocean tsunami, shares a light moment with his father Murugupillai at his residence in Kurukkalmadam, Sri Lanka, Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

Jayarasa Abilash, known as Baby 81 after he was swept away by the 2004 Indian ocean tsunami, stands in front of a monument built in memory of tsunami victims outside his residence in Kurukkalmadam, Sri Lanka, Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

The 2-month-old baby was washed away by the tsunami in eastern Sri Lanka and found some distance from home by rescuers. At the hospital, he was No. 81 on the admissions registry.

His father, Murugupillai Jayarasa, spent three days searching for his scattered family, with little left to his name in those early hours but a pair of shorts.

First he found his mother, then his wife. But their infant son was missing.

A nurse had taken the baby from the hospital, but returned him after hearing that his family was alive.

The ordeal, however, was far from over. Nine other families had submitted their names to the hospital, claiming “Baby 81” as their own, so the hospital administration refused to hand over the child to Jayarasa and his wife without proof.

The family went to the police. The matter went to court. The judge ordered a DNA test, a process that was still in its early stages in Sri Lanka.

But none of the nine other families claimed the baby legally, and no DNA testing was done on them, Jayarasa said.

“The hospital named the child ‘Baby 81’ and listed the names of nine people who claimed the child, omitting us,” he said.

“There was a public call to all those who said the child was theirs to subject themselves for DNA testing, but none of them came forward,” he recalled. Jayarasa said his family gave DNA samples and it was proven the child was theirs.

Soon, the family was reunited. Their story drew international media attention, and they even visited the United States for an interview.

Today, Abilash is sitting for his final high school exam. Solid and good-natured, he hopes to attend a university to study information technology.

He said he grew up hearing about his story from his parents, while classmates teased him by calling him “Baby 81" or “tsunami baby.” He was embarrassed, and it worsened every time the anniversary of the tsunami arrived.

“I used to think ‘Here they have come’ and run inside and hide myself," he said as journalists returned to hear his story again.

His father said the boy was so upset he wouldn’t eat at times.

“I consoled him saying, 'Son, you are unique in being the only one to have such a name in this world," he said.

Later, as a teenager, Abilash read more about the events that tore him from his family and brought him back, and he lost his fear.

He knows the nickname will follow him for life. But that's all right.

“Now I only take it as my code word," he said, joking. “If you want to find me out, access that code word.”

He continues to search online to read about himself.

His father said memories of those frantic, searching days 20 years ago remain fresh, even as others fade.

Over the years, the extensive publicity his family received has also affected them negatively, Jayarasa said.

His family was excluded from many of the tsunami relief and reconstruction programs because government officials assumed they had received money during their visit to the U.S.

The experience also led to jealousy, gossiping and ostracizing of the family in their neighborhood, forcing them to relocate.

The father wants his son and other family members to remain grateful for their survival, and he wants Abilash to become someone who can help others in need.

From time the boy was a toddler, his father collected small amounts of money from his work at a hairdressing shop. When Abilash turned 12, the family erected a small memorial to victims of the tsunami in their front yard. It shows four cupped hands.

The father explained: “A thought arose in my mind that since all those who have died have gone, leaving Abilash behind for us, why not a memorial site of our own to remember them every day."

FILE - Jayarasa Abilash, popularly known as 'Baby 81", naps in the arms of his mother Jenita, as his father, Murugupillai, helps make him comfortable during a photo opportunity in New York, Wednesday, March 2, 2005. (AP Photo/Mary Altaffer, File)

FILE - Jenita Jayarasa, left, the mother claimant of the infant dubbed "Baby 81" holds the child and father claimant Murugupillai Jayarasa, center, shouts as a doctor, center, tries to prevent them from taking the infant, inside a ward at a hospital in Kalmunai, about 210 kilometers (131 miles) east of Colombo, Sri Lanka, Wednesday, Feb. 2, 2005. (AP Photo/Rafiq Maqbool, File)

FILE- A Sri Lankan policeman guards the tsunami survivor infant dubbed "Baby 81" inside a ward as people watch from outside at a hospital in Kalmunai, about 210 kilometers (131 miles) east of Colombo, Sri Lanka, Feb. 3, 2005. (AP Photo/Rafiq Maqbool, File)

Jayarasa Abilash, known as Baby 81 after he was swept away by the 2004 Indian ocean tsunami, smiles as he speaks to Associated Press at his residence in Kurukkalmadam, Sri Lanka, Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

Floral tributes sit at a monument for the victims of 2004 Indian ocean tsunami at the residence of Jayarasa Abilash known as Baby 81 after he was swept away by the 2004 Indian ocean tsunami in Kurukkalmadam, Sri Lanka, Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

Jayarasa Abilash, known as Baby 81 after he was swept away by the 2004 Indian ocean tsunami, goes through his photo album at his residence in Kurukkalmadam, Sri Lanka, Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

People ride past the surroundings of Jayarasa Abilash, known as Baby 81 after he was swept away by the 2004 Indian ocean tsunami, in Kalmunai, Sri Lanka, Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

Jayarasa Abilash, known as Baby 81 after he was swept away by the 2004 Indian ocean tsunami, goes through his photo album at his residence in Kurukkalmadam, Sri Lanka, Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

Jayarasa Abilash, known as Baby 81 after he was swept away by the 2004 Indian ocean tsunami goes through his photo album at his residence in Kurukkalmadam, Sri Lanka, Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

Jayarasa Abilash, left, known as Baby 81 after he was swept away by the 2004 Indian ocean tsunami stands in front of a monument built in memory of tsunami victims out side his residence with his father Murugupillai in Kurukkalmadam, Sri Lanka, Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

Jayarasa Abilash, known as Baby 81 after he was swept away by the 2004 Indian ocean tsunami, stands in front of a monument built in memory of tsunami victims outside his residence with his father Murugupillai in Kurukkalmadam, Sri Lanka, Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

Jayarasa Abilash, right, known as Baby 81 after he was swept away by the 2004 Indian ocean tsunami, shares a light moment with his father Murugupillai at his residence in Kurukkalmadam, Sri Lanka, Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

Jayarasa Abilash, known as Baby 81 after he was swept away by the 2004 Indian ocean tsunami, stands in front of a monument built in memory of tsunami victims outside his residence in Kurukkalmadam, Sri Lanka, Tuesday, Dec. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

All you have to do to become a South Dakota resident is spend one night.

Stay in a campground or hotel and then stop by one of the businesses that specialize in helping people become South Dakotans, and they’ll help you do the paperwork to gain residency in a state with no income tax and relatively cheap vehicle registration.

The system brings in extra government revenue through vehicle fees and offers refuge to full-time travelers who wouldn’t otherwise have a permanent address or a place to vote.

And that’s the problem. State leaders are at a stalemate between those who say people who don’t really live in South Dakota shouldn’t be allowed to vote in local elections and those who say efforts to impose a longer residency requirement for voting violate the principle that everyone gets to vote.

And at least one state has gotten wind that its residents might be avoiding high income taxes with easy South Dakota residency and is investigating.

Easy South Dakota residency for nomads has become an enterprising opportunity for businesses such as RV parks and mail forwarders.

“That’s the primary concept here, is the people that have given up their sticks and bricks and now are on wheel estate, we call it, and they’re full-time traveling,” said Dane Goetz, owner of the Spearfish-based South Dakota Residency Center, which caters to full-time travelers. “They need a place to call home, and we provide that address for them to do that, and they are just perpetually on the move.”

Goetz estimated more than 30,000 people are full-time traveler residents of South Dakota, but the actual number is unclear. The state Department of Public Safety, which handles driver licensing, says it doesn't track the number of full-time traveler applications.

Officials of the South Dakota Secretary of State's Office did not respond to emailed questions or a phone message seeking the state's tally of full-time travelers registered to vote. The office is not responsible for enforcing residency requirements, Division of Elections Director Rachel Soulek said.

Victor Robledo, his wife and their five kids hit the road a decade ago in a 28-foot (8.5-meter) motorhome to seek adventure and ease their high cost of living in Southern California. They found South Dakota to be an opportunity to save money, receive mail and “take a residency in a state that really nurtures us,” he said. They filed for residency in 2020.

“It was as simple as coming into the state, staying one night in one of the campgrounds, and once we do that, we bring in a receipt to the office, fill out some paperwork, change our licenses. I mean, really, you can blow through there — gosh, 48 hours,” Robledo said.

Residency becomes thorny around voting. Some opponents don’t want people who don’t physically live in South Dakota to vote in its elections.

“I don’t want to deny somebody their right to vote, but to think that they can vote in a school board election or a legislative election or a county election when they’re not part of the community, I’m troubled by that,” said Democratic Rep. Linda Duba, who cited 10,000 people or roughly 40% of her Sioux Falls constituents being essentially mailbox residents. She likes to knock on doors and meet people but said she is unable to do “relationship politics” with travelers.

The law the Republican-controlled Legislature passed in 2023 added requirements for voter registration, including 30 days of residency — which don't have to be consecutive — and having “an actual fixed permanent dwelling, establishment, or any other abode to which the person returns after a period of absence.”

The bill's prime sponsor, Republican Sen. Randy Deibert, told a Senate panel that citizens expressed concerns about “people coming to the state, being a resident overnight and voting (by) absentee ballot or another way the next day and then leaving the state.”

Those registered to vote before the new law took effect remain registered, but some who tried to register since its passage had trouble. Dozens of people recently denied voter registration contacted the American Civil Liberties Union of South Dakota, according to the chapter’s advocacy manager, Samantha Chapman.

Durational residency requirements for voting are, in general, unconstitutional because such restrictions interfere with the interstate right to travel, said David Schultz, a Hamline University professor of political science and a professor of law at the University of St. Thomas.

“It’s kind of this parochialism, this idea of saying that only people who are really in our neighborhood, who really live in our city have a sufficient stake in it, and the courts have generally been unsympathetic to those types of arguments because, more often than not, they’re used for discriminatory purposes,” he said.

Earlier this year, the Legislature considered a bill to roll back the 2023 law. It passed the Senate but stalled in the House.

During a House hearing on that bill, Republican Rep. Jon Hansen asked one full-time traveler when he was last in South Dakota and when he intends to return. The man said he was in the state a year earlier but planned to return in coming months. Another man who moved from Iowa to work overseas said he had not lived “for any period of time, physically” in South Dakota.

“I don’t think we should allow people who have never lived in this state to vote in our state,” Hansen said.

Republican Sen. David Wheeler, an attorney in Huron, said he expects litigation would be what forces a change. It's unlikely a change to the 30-day requirement would pass the Legislature now, he said.

“It is a complicated topic that involves federal and state law and federal and state voting rights, and it is difficult to bring everybody together on how to appropriately address that,” Wheeler said.

More than 1,600 miles (2,500 kilometers) east, Connecticut State Comptroller Sean Scanlon has asked prosecutors to look into whether some state employees who live in Connecticut may have skirted their tax obligations by claiming to be residents of South Dakota.

Connecticut has a graduated income tax rate of 3.0% to 6.99%. Connecticut cities and towns also impose a property tax on vehicles. South Dakota has none.

Scanlon and his office, which administers state employee retiree benefits, learned from a Hartford Courant columnist in September that some state retirees might be using South Dakota’s mail-forwarding services for nefarious reasons.

Asked if there are concerns about other Connecticut taxpayers who are not state retirees possibly misusing South Dakota’s lenient residency laws, the Department of Revenue Services would only say the agency is “aware of the situation and we’re working with our partners to resolve it.”

A South Dakota legislative panel broached the residency issue as recently as August, a meeting in which one lawmaker called the topic “the Gordian knot of politics.”

“It seems like it’s almost impossible to come to some clear and definitive statement as to what constitutes a residency with such a mobile population with people with multiple homes and addresses and political boundaries that are easy to see on a map but there’s so much cross-transportation across them,” Republican Sen. Jim Bolin said.

Dura reported from Bismarck, North Dakota. Associated Press Writer Susan Haigh in Hartford, Connecticut, contributed to this report.

FILE - Pennigton County voters head to the polls at Valley View Elementary School Gym on Election Day, on Nov. 5, 2024, in Rapid City, S.D. (Madison Willis/Rapid City Journal via AP, File)

Visitors take in the massive sculpture carved into Mount Rushmore at the Mount Rushmore National Memorial Thursday, Sept. 21, 2023, in, Keystone, S.D. (AP Photo/David Zalubowski)

A highway sign depicting Mount Rushmore and reading "Welcome to South Dakota. Great faces, great places" stands on the North Dakota-South Dakota border near Thunder Hawk, South Dakota, on Saturday, Oct. 12, 2024. (AP Photo/Jack Dura)