ISTANBUL (AP) — In a dim one-room apartment in one of Istanbul’s poorest neighborhoods, 11-year-old Atakan Sahin curls up on a threadbare sofa with his siblings to watch TV while their mother stirs a pot of pasta.

The simple meal is all the family of six can look forward to most evenings. Atakan, his two younger brothers and 5-year-old sister are among the one-third of Turkish children living in poverty.

Click to Gallery

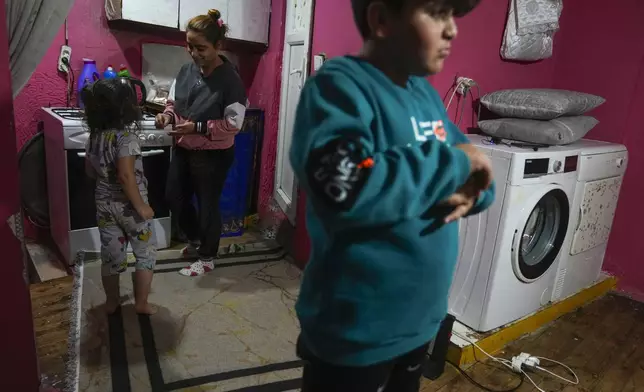

Rukiye Sahin, 28, talks to her daughter Dilan, 5, near her son Atakan, 11, in the family's one-room apartment in the Tarlabasi neighborhood in Istanbul, Turkey, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

A manually operated carousel is seen in the Tarlabasi neighborhood in Istanbul, Turkey, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

A boy pulls a cart as he scavenges for items in the Kadikoy district in Istanbul, Turkey, Saturday, Dec. 7, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

A girl sells flowers to passersby on the Karakoy sea promenade in Istanbul, Turkey, Friday, Dec. 6, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

A boy scavenges for items from a trash can in the Kadikoy district in Istanbul, Turkey, Saturday, Dec. 7, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

Young girls sell tissues to passersby on the Karakoy sea promenade in Istanbul, Turkey, Saturday, Dec. 7, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

A child tries on a pair of new boots that were handed out by volunteers in the Tarlabasi neighborhood in Istanbul, Turkey, Saturday, Dec. 14, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

Children and their families wait their turn as coats and shoes are handed out by volunteers in the Tarlabasi neighborhood in Istanbul, Turkey, Saturday, Dec. 14, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

Mehmet Yeralan, 53, a volunteer, talks to a local woman with her child in the Tarlabasi neighborhood in Istanbul, Turkey, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

A girl sells plastic items to people in the Kadikoy district in Istanbul, Turkey, Saturday, Dec. 7, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

Dilan Sahin, 5, tires to reach her toys in her family's one-room apartment in the Tarlabasi neighborhood in Istanbul, Turkey, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

A plate of pasta sits on a tablecloth in the Sahin family's one-room apartment in the Tarlabasi neighborhood in Istanbul, Turkey, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

Rukiye Sahin, 28, talks to her daughter Dilan, 5, near her son Atakan, 11, in the family's one-room apartment in the Tarlabasi neighborhood in Istanbul, Turkey, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

Children's laundry hangs over a street in the Tarlabasi neighborhood in Istanbul, Turkey, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

Local boys gather pieces of wood to burn for heat in the Tarlabasi neighborhood in Istanbul, Turkey, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

Residents gather pieces of wood to burn for heat in the Tarlabasi neighborhood in Istanbul, Turkey, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

A girl sells flowers to passersby on the Karakoy sea promenade in Istanbul, Turkey, Friday, Dec. 6, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

A boy pulls a cart to collect items as he scavenges in the Kadikoy district in Istanbul, Turkey, Monday, Dec. 16, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

“Look at the state of my children,” said Rukiye Sahin, 28. “I have four children. They don’t get to eat chicken, they don’t get to eat meat. I send them to school with torn shoes.”

Persistently high inflation, triggered by currency depreciation and unconventional economic policies that President Recep Tayyip Erdogan pursued but later abandoned, has left many families struggling to pay for food and housing. Experts say it's creating a lost generation of children who have been forced to grow up too quickly to help their families eke out an existence.

According to a 2023 joint report by UNICEF and the Turkish Statistical Institute, about 7 million of Turkey's roughly 22.2 million children live in poverty.

That deprivation is brought into stark focus in neighborhoods such as Istanbul’s Tarlabasi, where the Sahin family lives just a few minutes’ walk from Istiklal Avenue, a tourism hot spot bristling with brightly lit shops and expensive restaurants.

Meanwhile, the Sahins eat sitting on the floor of their room — the same floor Rukiye and her husband sleep on while their children occupy the room’s sofas. In the chilly early December night, a stove burns scraps of wood to keep them warm. They sometimes fall asleep to the sound of rats scuttling through the building.

Atakan spends his days helping his father scour dumpsters in search of recyclable material to earn the family a meager income.

Poor children in Istanbul also earn money for their families by selling small items such as pens, tissues or bracelets at the bars and cafes in the city's entertainment districts, often working late into the night.

“I can’t go to school because I have no money,” he said. “We have nothing. Can you tell me how I can go? On sunny days, when I don’t go to school, I collect plastic and other things with my father. We sell whatever we find.”

The cash helps buy basic foodstuffs and pay for his siblings to attend school. On the days Atakan can attend, he is ill-equipped to succeed, lacking proper shoes, a coat and textbooks for the English class he loves.

The Sahins struggle to scrape together the money to cover the rent, utilities and other basic expenses as Turkey’s cost-of-living crisis continues to rage. Inflation stood at 47% in November, having peaked at 85% in late 2022. Prices of food and nonalcoholic drinks were 5.1% higher in November than in the previous month.

Under these circumstances, a generation of children is growing up rarely enjoying a full meal of fresh meat or vegetables.

Rukiye and her husband receive 6,000 lira ($173) per month in government welfare to help towards school costs, but they pay the same amount in rent for their home.

“My son says, ‘Mom, it’s raining, my shoes are soaking wet.’ But what can I do?” Rukiye said. “The state doesn’t help me. I’m in this room alone with my children. Who do I have except them?”

The picture of children rummaging through garbage to help support their families is far from the image Turkey presents to the world: that of an influential world power with a vibrant economy favorable to foreign investment.

Erdogan is proud of the social programs his party has introduced since he came to power more than 20 years ago, boasting that the “old days of prohibitions, oppression, deprivation and poverty are completely behind us.”

Speaking at the G20 summit in November, Erdogan described Turkey’s social security system as “one of the most comprehensive and inclusive” in the world. “Our goal is to ensure that not a single poor person remains. We will continue our work until we achieve this,” he said.

Finance Minister Mehmet Simsek, tasked with implementing austerity and taming inflation, said the 17,000 lira ($488) monthly minimum wage isn't low. But he has pledged to raise it as soon as possible.

Although the government allocates billions of lira to struggling households, inflation, which most people agree is far above the official figure, eats into any aid the state can give.

In districts such as Tarlabasi, rents have risen five-fold in recent years due to gentrification in central Istanbul that puts pressure on the housing market for low-income families.

Experts say welfare payments aren't enough for the millions who rely on them, forcing many parents to make impossible choices: Should they pay the rent or buy clothing for the children? Should they send them to school or keep them home to earn a few extra lira?

Volunteers are trying to ease the cycle of deprivation.

Mehmet Yeralan, a 53-year-old former restaurant owner, brings essentials to Tarlabasi’s poor people that they can't afford, including coats, notebooks and the occasional bag of rice.

“Our children do not deserve this,” he said, warming himself by a barrel of burning scrap wood on the street. “Families are in very difficult situations. They cannot buy food for their children and send them to school. Children are on the streets, selling tissues to support their families. We are seeing deep poverty here.”

Hacer Foggo, a poverty researcher and activist, said Turkey is raising a lost generation who are forced to drop out of school to work or are channeled into vocational programs where they work four days and study one day per week, receiving a small fraction of the minimum wage.

“Look at the situation of children,” she said. “Two million of them are in deep poverty. Child labor has become very common. Families choose these education-work programs because children bring in some income. It’s not a real education, just cheaper labor.”

Foggo points to research showing how early childhood education can help break cycles of poverty. Without it, children remain trapped — stunted physically and educationally, and condemned to lifelong disadvantages.

UNICEF placed Turkey 38th out of 39 European Union or Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries in terms of child poverty between 2019 and 2021, with a child poverty rate of 34%.

The tragic consequences of this destitution occasionally burst into the public arena.

The deaths of five children in a fire in the western city of Izmir in November happened while their mother was out collecting scrap to sell. The image of their sobbing father, who was escorted from prison in handcuffs to attend his children’s funeral, caused widespread outrage at the desperation and helplessness facing poor families.

It is a situation Rukiye fully understands.

“Sometimes I go to bed hungry, sometimes I go to bed full,” she said. “We can’t move forward, we always fall behind. ... When you don’t have money in your hands, you always fall behind.”

Her eldest son, meanwhile, clings to his childhood dreams. “I want my own room,” Atakan said. “I want to go to school regularly. I want everything to be in order. … I’d like to be a football player one day, to support my family.”

Badendieck reported from Istanbul. Andrew Wilks in Istanbul and Suzan Fraser in Ankara, Turkey, contributed.

A manually operated carousel is seen in the Tarlabasi neighborhood in Istanbul, Turkey, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

A boy pulls a cart as he scavenges for items in the Kadikoy district in Istanbul, Turkey, Saturday, Dec. 7, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

A girl sells flowers to passersby on the Karakoy sea promenade in Istanbul, Turkey, Friday, Dec. 6, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

A boy scavenges for items from a trash can in the Kadikoy district in Istanbul, Turkey, Saturday, Dec. 7, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

Young girls sell tissues to passersby on the Karakoy sea promenade in Istanbul, Turkey, Saturday, Dec. 7, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

A child tries on a pair of new boots that were handed out by volunteers in the Tarlabasi neighborhood in Istanbul, Turkey, Saturday, Dec. 14, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

Children and their families wait their turn as coats and shoes are handed out by volunteers in the Tarlabasi neighborhood in Istanbul, Turkey, Saturday, Dec. 14, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

Mehmet Yeralan, 53, a volunteer, talks to a local woman with her child in the Tarlabasi neighborhood in Istanbul, Turkey, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

A girl sells plastic items to people in the Kadikoy district in Istanbul, Turkey, Saturday, Dec. 7, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

Dilan Sahin, 5, tires to reach her toys in her family's one-room apartment in the Tarlabasi neighborhood in Istanbul, Turkey, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

A plate of pasta sits on a tablecloth in the Sahin family's one-room apartment in the Tarlabasi neighborhood in Istanbul, Turkey, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

Rukiye Sahin, 28, talks to her daughter Dilan, 5, near her son Atakan, 11, in the family's one-room apartment in the Tarlabasi neighborhood in Istanbul, Turkey, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

Children's laundry hangs over a street in the Tarlabasi neighborhood in Istanbul, Turkey, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

Local boys gather pieces of wood to burn for heat in the Tarlabasi neighborhood in Istanbul, Turkey, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

Residents gather pieces of wood to burn for heat in the Tarlabasi neighborhood in Istanbul, Turkey, Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

A girl sells flowers to passersby on the Karakoy sea promenade in Istanbul, Turkey, Friday, Dec. 6, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

A boy pulls a cart to collect items as he scavenges in the Kadikoy district in Istanbul, Turkey, Monday, Dec. 16, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

VATICAN CITY (AP) — Pope Francis in his traditional Christmas message on Wednesday urged “all people of all nations” to find courage during this Holy Year “to silence the sounds of arms and overcome divisions” plaguing the world, from the Middle East to Ukraine, Africa to Asia.

The pontiff's “Urbi et Orbi” — “To the City and the World” — address serves as a summary of the woes facing the world this year. As Christmas coincided with the start of the 2025 Holy Year celebration that he dedicated to hope, Francis called for broad reconciliation, “even (with) our enemies.”

"I invite every individual, and all people of all nations ... to become pilgrims of hope, to silence the sounds of arms and overcome divisions,'' the pope said from the loggia of St. Peter's Basilica to throngs of people below.

The pope invoked the Holy Door of St. Peter’s, which he opened on Christmas Eve to launch the 2025 Jubilee, as representing God’s mercy, which “unties every knot; it tears down every wall of division; it dispels hatred and the spirit of revenge.”

He called for arms to be silenced in war-torn Ukraine and in the Middle East, singling out Christian communities in Israel and the Palestinian territories, “particularly in Gaza where the humanitarian situation is extremely grave,” as well as Lebanon and Syria “at this most delicate time.”

Francis repeated his calls for the release of hostages taken from Israel by Hamas on Oct. 7, 2023.

He cited a deadly outbreak of measles in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the suffering of the people of Myanmar, forced to flee their homes by “the ongoing clash of arms.” The pope likewise remembered children suffering from war and hunger, the elderly living in solitude, those fleeing their homelands, who have lost their jobs, and are persecuted for their faith.

Pilgrims were lined up on Christmas Day to walk through the great Holy Door at the entrance of St. Peter’s as the Jubilee is expected to bring some 32 million Catholic faithful to Rome.

Traversing the Holy Door is one way that the faithful can obtain indulgences, or forgiveness for sins during a Jubilee, a once-every-quarter-century tradition that dates from 1300.

Pilgrims submitted to security controls, amid new security fears following a deadly Christmas market attack in Germany. Many paused to touch the door and made the sign of the cross upon entering the basilica dedicated to St. Peter, the founder of the Roman Catholic Church.

“You feel so humble when you go through the door, that once you go through it is almost like a release, a release of emotions,'' said Blanca Martin, a pilgrim from San Diego. "... You feel like now you are able to let go and put everything in the hands of God. See, I am getting emotional. It’s just a beautiful experience.”

Hanukkah, Judaism’s eight-day Festival of Lights, begins this year on Christmas Day, which has only happened four times since 1900.

The calendar confluence has inspired some religious leaders to host interfaith gatherings, such as a Hanukkah party hosted last week by several Jewish organizations in Houston, Texas, bringing together members of the city’s Latino and Jewish communities for latkes, the traditional potato pancake eaten on Hanukkah, topped with guacamole and salsa.

While Hanukkah is intended as an upbeat, celebratory holiday, rabbis note that it’s taking place this year as wars rage in the Middle East and fears rise over widespread incidents of antisemitism. The holidays overlap infrequently because the Jewish calendar is based on lunar cycles and is not in sync with the Gregorian calendar, which sets Christmas on Dec. 25. The last time Hanukkah began on Christmas Day was in 2005.

In the front lines of eastern Ukraine, soldiers spent another Christmas locked in grinding battles with Russian forces. It is their second Christmas at war and away from home since the February 2022 full-scale invasion.

A soldier with the call sign OREL, the Ukrainian commander of 211th battalion said he had forgotten it was Christmas day.

“Honestly, I remembered about this holiday only in the evening (after) someone wrote in the group that today is a holiday,'' he said. “We have no holidays, no weekends. ... I don’t know, I have no feelings, everything is plain, everything is gray, and my thoughts are only about how to preserve my personnel and how to stop the enemy.”

Others, however, said that the day brought hope that there would one day be peace. Ukrainians expect the inauguration of president-elect Donald Trump will bring about a ceasefire deal, and many soldiers who have borne the brunt of nearly three years of fighting, said they hoped that would be the case.

Valerie, a Ukrainian solider of the 24th Mechanized Brigade, who only provided his first name, said

“On such a day, today, I’d like to wish for all of this to be over, for everyone,'' said Valerie, a Ukrainian soldier in the 24th Mechanized Brigade who would only give his first name. “Of course, there is always hope, there is always hope. Everyone wants peace, everyone wants peace and to return home,'”

Military chaplain Roman Kostenko of the 117th Separate Heavy Mechanized Brigade said that soldiers unable to be with their famililes are “united by our military family.”

Christians in Nineveh Plains attended Christmas Mass on Tuesday at the Mar Georgis church in the center of Telaskaf, Iraq, with security concerns about the future. “We feel that they will pull the rug out from under our feet at any time. Our fate is unknown here,” said Bayda Nadhim, a resident of Telaskaf.

Iraq’s Christians, whose presence there goes back nearly to the time of Christ, belong to a number of rites and denominations. They once constituted a sizeable minority in Iraq, estimated at around 1.4 million.

But the community has steadily dwindled since the 2003 US-led invasion and further in 2014 when the Islamic State militant group swept through the area. The exact number of Christians left in Iraq is unclear, but they are thought to number several hundred thousand.

German celebrations were darkened by a car attack on a Christmas market in Magdeburg on Friday that left five people dead, including a 9-year-old boy, and 200 people injured. President Frank-Walter Steinmeier rewrote his recorded Christmas Day speech to address the attack, saying that “there is grief, pain, horror and incomprehension over what took place in Magdeburg.” He urged Germans to “stand together” and that “hate and violence must not have the last word.”

A 50-year-old Saudi doctor who had practiced medicine in Germany since 2006 was arrested on suspicion of murder, attempted murder and bodily harm. The suspect’s X account describes him as a former Muslim and is filled with anti-Islamic themes. He criticized authorities for failing to combat “the Islamification of Germany” and voiced support for the anti-immigration Alternative for Germany (AfD) party.

Massachusetts school children have come up with names for a dozen hardworking snowplows, including “Taylor Drift,” “Control-Salt-Delete” and “It’s Snow Problem.” The Massachusetts Department of Transportation this week announced the winners of its competition to name the snowplows, which was open to elementary and middle school students. Other winning names included “Meltin’ John,” “Ice Ice Baby” and the “Abominable Plowman.”

———

Barry reported from Milan. Associated Press writers Melanie Lidman in Jerusalem, Rashid Yehya in Teleskaf, Iraq, Evgeniy Maloletka in Ukraine, Nick Perry in Boston, MA and David McHugh in Frankfurt, Germany contributed to this report.

Pope Francis looks on after delivering the Urbi et Orbi (Latin for 'to the city and to the world' ) Christmas' day blessing from the main balcony of St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Wednesday, Dec. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini)

Pope Francis sits before delivering the Urbi et Orbi (Latin for 'to the city and to the world' ) Christmas' day blessing from the main balcony of St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Wednesday, Dec. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini)

Pope Francis delivers the Urbi et Orbi (Latin for 'to the city and to the world' ) Christmas' day blessing from the main balcony of St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Wednesday, Dec. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini)

Pope Francis delivers the Urbi et Orbi (Latin for 'to the city and to the world' ) Christmas' day blessing from the main balcony of St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Wednesday, Dec. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini)

Pope Francis delivers the Urbi et Orbi (Latin for 'to the city and to the world' ) Christmas' day blessing from the main balcony of St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Wednesday, Dec. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini)

Pope Francis waves before delivering the Urbi et Orbi (Latin for 'to the city and to the world' ) Christmas' day blessing from the main balcony of St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Wednesday, Dec. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini)

Swiss Guards march in front of St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Wednesday, Dec. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini)

Swiss Guards march in front of St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Wednesday, Dec. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini)

Christians attend the Christmas Mass at Sacred Heart Cathedral Church, in Lahore, Pakistan, Wednesday, Dec. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/K.M. Chaudary)

Latin Patriarch Pierbattista Pizzaballa, center, leads the Christmas morning Mass at the Chapel of Saint Catherine, traditionally believed to be the birthplace of Jesus, in the West Bank city of Bethlehem, Wednesday, Dec. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

A nun holds a child to light a candle before the Christmas morning Mass at the Chapel of Saint Catherine, traditionally believed to be the birthplace of Jesus, in the West Bank city of Bethlehem, Wednesday, Dec. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Latin Patriarch Pierbattista Pizzaballa leads the Christmas midnight Mass at the Church of the Nativity traditionally believed to be the birthplace of Jesus, in the West Bank city of Bethlehem, Wednesday Dec. 25, 2024. (Alaa Badarneh/Pool via EPA)

Fireworks burst over Saydnaya Convent during the lighting of the Christmas tree, in Saydnaya town on the outskirts of Damascus, Syria, Tuesday, Dec. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Hussein Malla)

Houses are seen along the mountain as a cross stands over the Greek Orthodox convent Saint Takla on Christmas Eve in Maaloula, some 60 km northern Damascus, Syria, Tuesday, Dec. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Leo Correa)

Christians attend the Christmas midnight Mass at the Church of the Nativity traditionally believed to be the birthplace of Jesus, in the West Bank city of Bethlehem, Tuesday Dec. 24, 2024. (Alaa Badarneh/Pool via EPA)

Christians attend the Christmas mass in the Greek Orthodox convent Saint Takla, in Maaloula, some 60 km northern Damascus, Syria, Tuesday, Dec. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Leo Correa)

Rabbi Yehuda Teichtal, right, and Rabbi Shmuel Segal, left, watch the set-up of a giant Hanukkah Menorah by the Jewish Chabad Educational Center ahead of the Jewish Hanukkah holiday, in front of the Brandenburg Gate at the Pariser Platz in Berlin, Germany, Monday, Dec. 23, 2024. (AP Photo/Markus Schreiber)

Faithful arrive to walk through the Holy Door of St.Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Wednesday, Dec. 25, 2024, after it was opened by Pope Francis on Christmas Eve marking the start of the Catholic 2025 Jubilee. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini)

Faithful take photos as they arrive to walk through the Holy Door of St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Wednesday, Dec. 25, 2024, after it was opened by Pope Francis on Christmas Eve marking the start of the Catholic 2025 Jubilee. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini)

Faithful walk through the Holy Door of St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Wednesday, Dec. 25, 2024, after it was opened by Pope Francis on Christmas Eve marking the start of the Catholic 2025 Jubilee. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini)

Faithful walk through the Holy Door of St.Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Wednesday, Dec. 25, 2024, after it was opened by Pope Francis on Christmas Eve marking the start of the Catholic 2025 Jubilee. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini)

Faithful arrive to walk through the Holy Door of St.Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Wednesday, Dec. 25, 2024, after it was opened by Pope Francis on Christmas Eve marking the start of the Catholic 2025 Jubilee. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini)

Faithful walk through the Holy Door of St.Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Wednesday, Dec. 25, 2024, after it was opened by Pope Francis on Christmas Eve marking the start of the Catholic 2025 Jubilee. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini)

Faithful walk through the Holy Door of St.Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Wednesday, Dec. 25, 2024, after it was opened by Pope Francis on Christmas Eve marking the start of the Catholic 2025 Jubilee. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini)

Faithful walk through the Holy Door of St.Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Wednesday, Dec. 25, 2024, after it was opened by Pope Francis on Christmas Eve marking the start of the Catholic 2025 Jubilee. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini)

Faithful walk through the Holy Door of St.Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Wednesday, Dec. 25, 2024, after it was opened by Pope Francis on Christmas Eve marking the start of the Catholic 2025 Jubilee. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini)

A man stops in prayer as he walks through the Holy Door of St.Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Wednesday, Dec. 25, 2024, after it was opened by Pope Francis on Christmas Eve marking the start of the Catholic 2025 Jubilee. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini)