TAIPEI, Taiwan (AP) — Prosecutors in Taiwan indicted former presidential candidate and Taiwan People's Party founder Ko Wen-je on corruption charges Thursday, accusing him of taking bribes during his time as mayor of the island's capital.

Ko, a former mayor of Taipei, is accused of accepting bribes related to a real estate development during his time in office, according to the prosecutors' statement. He's also accused of embezzling political donations.

If convicted on all charges, he faces a possible 28.5 years in jail.

Core to the case is a development owned by Core Pacific City group in Taipei. Prosecutors say Ko allowed the company to evade city building regulations in exchange for bribes.

“The defendant, Ko, violated his vow as a mayor to not accept bribes, and abide by our national laws. Instead, Ko intended to help the group obtain billions of dollars in illegal benefits, while collecting millions in bribes,” said Kao Yi-shu, the lead prosecutor, while unveiling the charges Thursday.

While Ko could not be reached, he has previously denied the allegations of bribery and corruption. His party said the charges were a case of political persecution.

"With this kind of abuse of power, the government is being reduced to a political thug,” said Lin Fu-nan, a member of the TPP’s central committee. “We call on the black hand of politics not to reach into the judiciary."

Ko, a former doctor, burst onto the political scene to win Taipei's 2014 mayoral race. He served two terms from 2014 to 2022.

Ko founded the TPP in 2019 as an alternative to the two-party system, promising a break from politics as usual.

He ran for President this year. Despite finishing third, he attracted attention for his appeal to young voters. Taiwan's politics is mostly dominated by two main political parties, the Nationalist Party (Kuomingtang) and the Democratic Progressive Party.

Ko's Taiwan People's Party, while small, is allied with the Kuomingtang in Taiwan's legislature and helped it pass three laws last week that critics say have paralyzed the Constitutional Court and will weaken Taiwan President Lai Ching-te's ability to carry out his political agenda.

Wu reported from Bangkok.

FILE - Taiwan People's Party (TPP) presidential candidate Ko Wen-je speaks at the presidential debates at Taiwan Public Television Service in Taipei, Taiwan, Dec. 30, 2023. (AP Photo/Pei Chen, Pool, File)

HEBBRONVILLE, Texas (AP) — In this corner of southern Texas, the plump cacti seem to pop out of arid dust and cracked earth, like magic dumplings.

It’s only here and in northern Mexico that the bluish-green peyote plant can be found growing naturally, nestled under thorny mesquite, acacia and blackbrush.

For many Native American Church members who call this region the “peyote gardens,” the plant is sacrosanct and an inextricable part of their prayer and ceremony. It’s believed to be a natural healer that Indigenous communities have counted on for their physical and mental health as they’ve dealt with the trauma of colonization, displacement, and erosion of culture, religion and language.

The cactus contains a spectrum of psychoactive alkaloids, the primary one being the hallucinogen mescaline, and is coveted for those psychedelic properties. Even though it is a controlled substance under federal law, an exemption afforded by a 1994 amendment to the American Indian Religious Freedom Act made it legal for Native Americans to use, possess and transport peyote for traditional religious purposes.

For over two decades, Native American practitioners of peyotism, whose numbers in the U.S. are estimated at 400,000, have raised the alarm about lack of access to peyote, which they reverently call “the medicine.” They say poaching and excessive harvesting of the slow-growing cactus, which flowers and matures over 10 to 30 years, are endangering the species and ruining its delicate habitat.

Native American Church members say the situation has worsened with demands from advocates of the psychedelic renaissance seeking to decriminalize peyote and make it more widely available for medical research and treatment of various ailments. Agriculture, housing developments, wind farms in the region and the border wall, are also damaging the habitat, experts say.

A vast majority of peyote people agree the plant must be protected and should be out of reach for medical researchers, Silicon Valley investors and other groups advocating peyote decriminalization. But there are diverse opinions within the Native American Church on how to accomplish that goal.

While at least one group spearheaded by Native American Church leaders has begun efforts to conserve and propagate peyote naturally in its habitat using philanthropic dollars, others in the church are more suspicious of investors' intentions, saying they fear exploitation and would rather get funding from the U.S. government to protect peyote.

Darrell Red Cloud, who is Oglala Lakota, remembers at age 4 using peyote and singing ceremonial songs at all-night peyote ceremonies with his family. Peyote has always been about forging a connection with the Creator, said Red Cloud. He's the vice president of the Native American Church of North America.

“Our people were not religious people, we were prayerful people.”

Frank Dayish, former vice president of the Navajo Nation and chairperson of the Council of the Peyote Way of Life Coalition, compared peyote to the Eucharist in Catholicism.

“Peyote is my religion,” he said. “Everything in my life has been based on prayers through that sacrament.”

Adrian Primeaux, who is Yankton Sioux and Apache, says he grew up hearing the story of a malnourished and dehydrated Apache woman who fell behind her group during a forced relocation by the U.S. government in the 1830s.

“She was about to give up on life as she lay close to the Earth when she heard a plant speaking to her," Primeaux said. "The peyote was telling her: Eat me and you will be well.”

She carried this plant back to Apache medicine men and elders who meditated and prayed with it, said Primeaux. He believes the Native American Church and what would become the Peyote Way of Life was unveiled during that spiritual quest.

Peyote is not just a medicinal herb — it is “a spiritual guide and a north star,” said Primeaux, who comes from five generations of peyote people. The plant has been a guiding light amid their traumatic history.

“It gave us hope and helped us process our thoughts, emotions and life purpose,” he said.

In October 2017, the National Council of Native American Churches purchased 605 acres in Hebbronville, Texas, to establish a peyote preserve and a “spiritual homesite” that is now run by the Indigenous Peyote Conservation Initiative or IPCI.

Steven Benally, a Navajo elder from Sweetwater, Arizona, and an IPCI board member, remembers his annual pilgrimages to the peyote gardens with his family. He recalls losing access to the gardens after the “peyotero” system took over, where government-licensed peyoteros harvested the button-like tops of the plant by the thousands and sold them to Native American Church members.

This meant that Native American people could not freely go onto privately owned ranches and prayerfully harvest peyote as they had done for generations. They lost their sacred connection with the land, Benally said.

It wasn’t until he threw open the gate to their sprawling ranch, affectionately called “the 605,” that Benally felt connected once again. He was so overcome by emotion that he placed a sign at the entrance with the words: “This is real.”

“It felt like we were finally living what we just dreamed, prayed and talked about,” he said.

One of Benally’s favorite spots on the property is a hilltop bench — a tranquil corner where visitors have placed prayer notes, painted rocks and other offerings to a nearby cluster of naturally sprouted peyote. Benally sits on the bench inhaling the gentle breeze and taking in the stillness.

“Our belief is that these plants, these animals, these birds are just like us,” he said. “They can hear, they can understand. They have their powers, they have their place, a purpose and a reason — just like us.”

The peyote preserve is a conservation site where the plant is not harvested but propagated and replanted naturally in its habitat without chemicals, said Miriam Volat, executive director for the nonprofit that oversees it. Native Americans who can produce their tribal identification cards can camp at the preserve and prayerfully harvest from amiable surrounding ranches, she said.

The goal is to restore peyote and its habitat, making it abundant in the region within the next 50 years.

Peyote grown in their nursery is under the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency’s watchful eye, she said. Licensed to operate, the nonprofit tries to balance being welcoming with satisfying the agency’s requirement to secure the plant behind locked gates and camera monitoring.

Those trying to protect peyote disagree on whether it should be grown outside its natural habitat. While scientists and conservationists say it is essential for the protection of the species, many Native American Church members say doing so would dilute its sacred nature.

Keeper Trout, a research scientist and co-founder of Texas-based Cactus Conservation Institute, remembers how abundantly peyote grew in the region during the 1970s. It’s all but disappeared.

“It was like walking on mattresses,” he said.

Trout empathizes with those who object on religious grounds, but he believes people should be able to cultivate and harvest anywhere. With a little help, Trout is confident the resilient plant can survive.

But many Native American Church members say where the plant grows matters. The ceremonial protocols were bestowed by the Creator’s grace and preserved through storytelling, said Hershel Clark, secretary for the Teesto chapter of the Azee Bee Nahagha of Diné Nation in Arizona.

“This is why we don’t support greenhouses, growing it outside its natural habitat or synthesizing it to make pills," Clark said.

Red Cloud fears those changes would harm its sacredness.

“Then, it just becomes a drug that people depend on rather than a spiritual medicine,” he said.

Funding peyote preservation and conservation efforts has been a challenge as well.

The Native American Church of North America is calling on the U.S government to uphold its obligation to protect and preserve peyote in its natural habitat in southern Texas, which includes financial incentives for landowners, said Red Cloud. His organization is asking for a $5 million federal grant to jumpstart such a program.

IPCI started with seed money from Riverstyx Foundation, which is run by Cody Swift, a psychotherapist and prominent supporter of psychedelic therapy research. The organization continues to seek philanthropic dollars to carry the conservation effort forward and is not opposed to receiving funding from the U.S. government, Volat said.

“But, we're not waiting for it,” she said.

There is suspicion and skepticism about Swift and other investors’ intentions in some corners of the Native American Church, Clark said. Swift has said in interviews that IPCI’s goal is to preserve peyote in its natural habitat under the leadership and guidance of Native American peyote people, a stance Volat, his co-director at the foundation, also affirms.

There is no question that opening peyote up to a broader market will create a supply crisis and increase access to those who have the financial resources, said Kevin Feeney, senior social sciences lecturer at Central Washington University in Ellensburg, Washington, who has studied the commodification of peyote.

Indigenous people would struggle to access their sacred plant while seeing others use it in a way they deem profane, he said.

Peyote supply remains limited for the Native American Church. Today, in southern Texas, only three licensed peyoteros are legally allowed to harvest the plant for sale to church members. Zulema “Julie” Morales, based in Rio Grande City, is one of them. She inherited the business from her father, Mauro Morales, who died two years ago.

She has been out in the fields since she was 10. Now 60, she says the peyote habitat is dwindling not because of peyoteros who harvest legally and ethically, but because of illegal poaching. She remembers her father gathering enough peyote to fill a dozen large trays while she can barely fill one.

Even though she is Mexican American and a Catholic, Morales, who charges 55 cents a button, considers it a privilege to provide peyote for ceremonial purposes. Her father, who customers called “grandpa,” hosted ceremonies for Native people every year and she has been a keen observer.

“As Mexican Americans, we value our traditions,” she said. “This is their tradition and it’s beautiful for us to be a part of that in our own way.”

At IPCI, one of the main goals is to teach future generations the value of getting back to their ancestors’ spiritual and healing ways, said Sandor Iron Rope, an Oglala Lakota spiritual leader and president of the Native American Church of South Dakota. At least 200 people gathered on IPCI’s grounds over Thanksgiving week, learning about peyote through panels, discussions, ceremony and prayer.

“We’ve put our moccasins and our footprints in this place,” Iron Rope said. “The hope is that these children, the next generation, will see the therapeutic value in getting rid of their phones and learning about what is right in front of them.”

Iron Rope says this is how he is fulfilling his responsibility to future generations.

“You can pray all you want, but you’re going to have to meet the Creator halfway somewhere,” he said. “You’re going to have to implement that prayer into action. And I see this as prayer in action.”

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

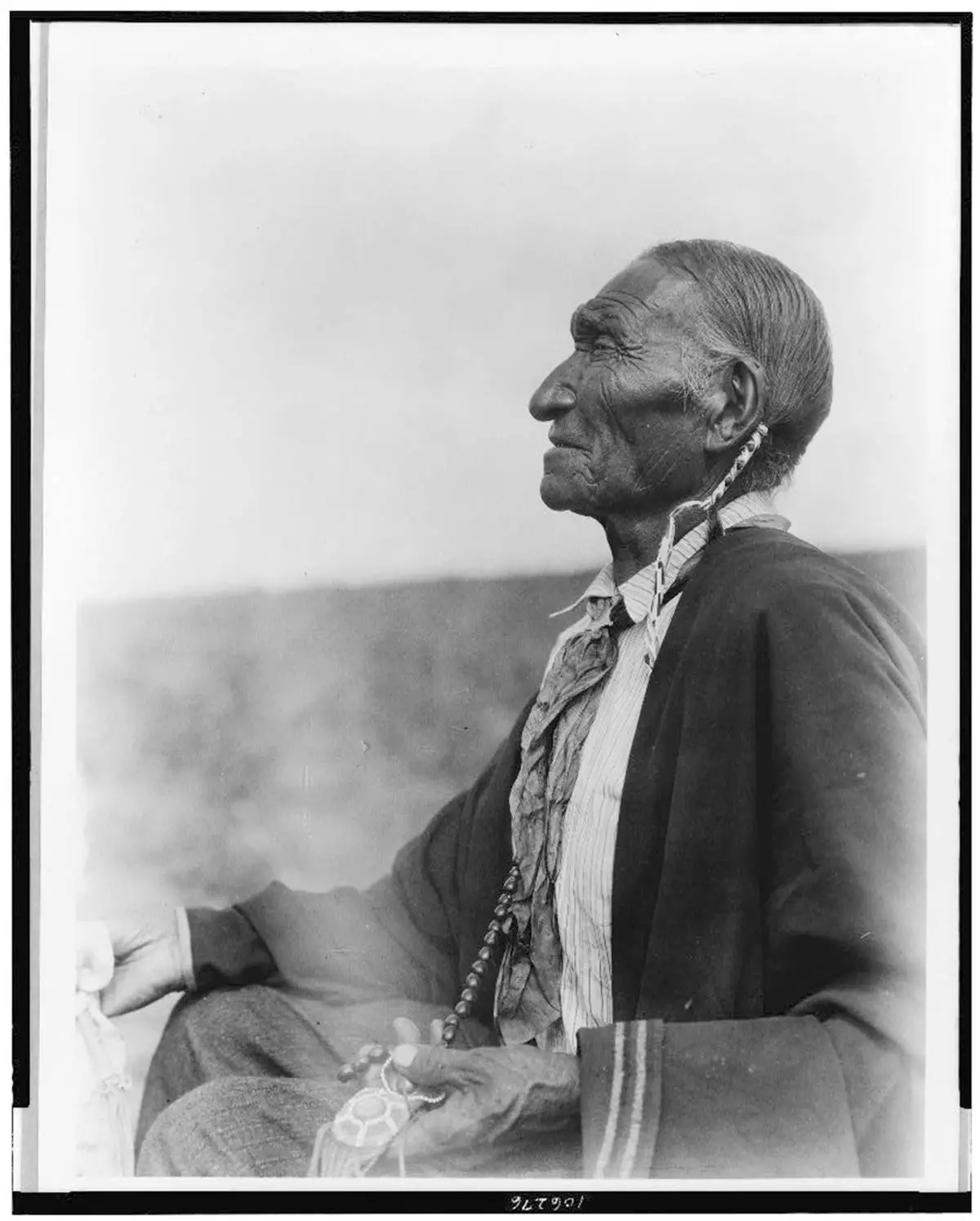

This photo provided by the Library of Congress shows a Cheyenne Peyote leader in 1927. (Edward S. Curtis Collection/Library of Congress via AP)

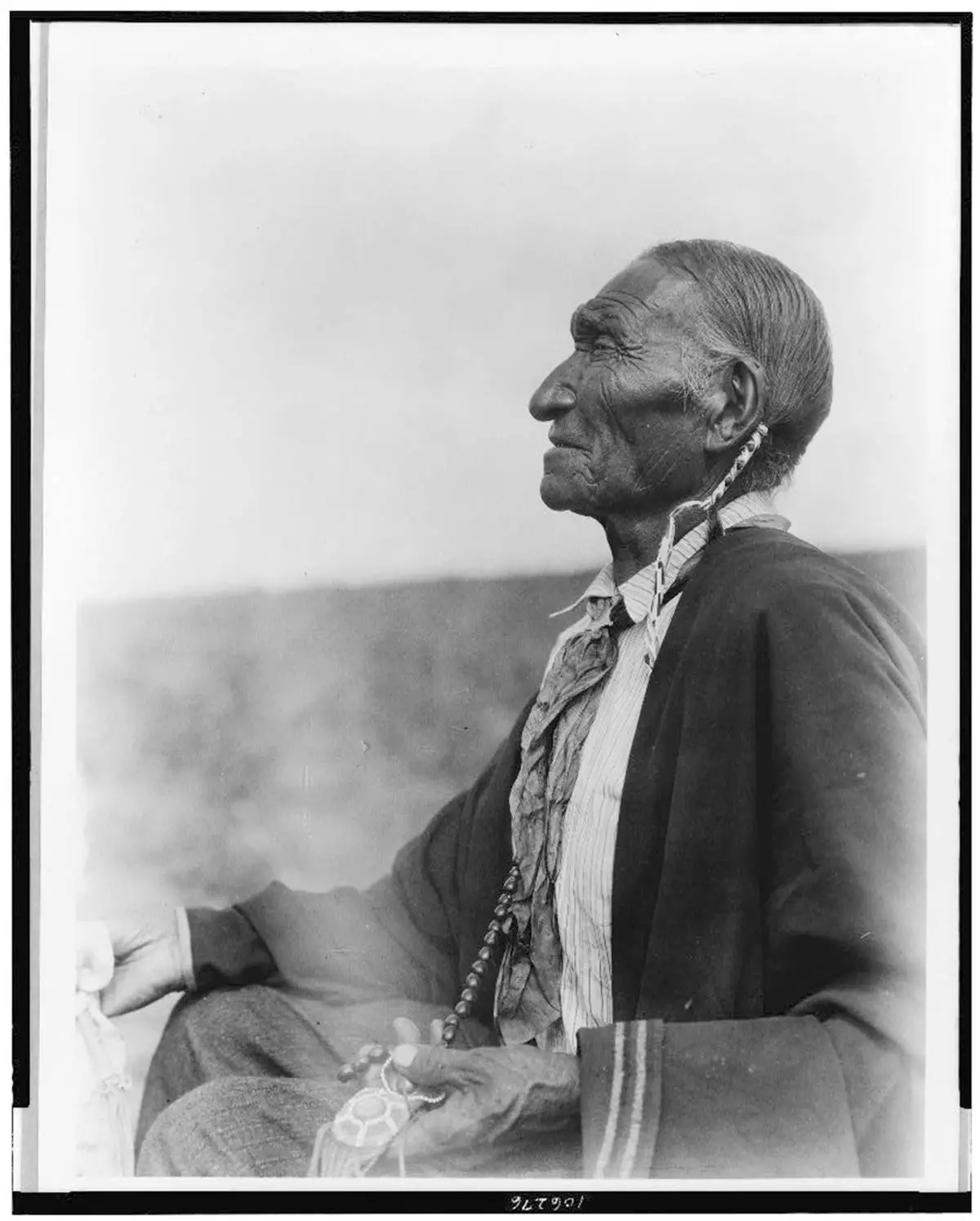

This photo provided by the Library of Congress shows Comanche Nation Chief, Quanah Parker, in 1909. Parker played a major role in creating the Native American Church, whose members use peyote in spiritual ceremony. (Library of Congress via AP)

Adrian Primeaux, of the Yankton Sioux and Apache, stands in the peyote nursery at the Indigenous Peyote Conservation Initiative, a spiritual homesite and peyote conservation site for Native American Church members on 605 acres of land in the peyote gardens of South Texas, Sunday, March 24, 2024, in Hebbronville, Texas. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Peyote plants growing in the nursery at the Indigenous Peyote Conservation Initiative homesite in Hebbronville, Texas, Tuesday, March 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Miriam Volat, executive director of the Indigenous Peyote Conservation Initiative and co-director of The River Styx Foundation, examines young peyote plants in the nursery at IPCI in Hebbronville, Texas, Sunday, March 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Peyote plants growing in the nursery at the Indigenous Peyote Conservation Initiative homesite in Hebbronville, Texas, Tuesday, March 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Adrian Primeaux, of the Yankton Sioux and Apache, opens the gates to a peyote nursery at the Indigenous Peyote Conservation Initiative, in Hebbronville, Texas, Sunday, March 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

A sign leading to the tipi grounds at the Indigenous Peyote Conservation Initiative homesite in Hebbronville, Texas, Sunday, March 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Yankton Sioux and Apache tribal member Adrian Primeaux, stands for a portrait at the Indigenous Peyote Conservation Initiative, a spiritual homesite and peyote conservation site for Native American Church members on 605 acres of land in the peyote gardens of South Texas, Monday, March 25, 2024, in Hebbronville, Texas. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

The offering garden at the Indigenous Peyote Conservation Initiative homesite, in Hebbronville, Texas, Tuesday, March 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Members of the Indigenous Peyote Conservation Initiative and various chapters of the Native American Church and ABNDN, Azee Bee Nahgha of Diné Nation, look for peyote growing in the wild, in Hebbronville, Texas, Tuesday, March 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Sandor Iron Rope, Oglala Lakota tribe member, president of the Native American Church of South Dakota and Indigenous Peyote Conservation Initiative board member, left, and Miriam Volat, executive director of the Indigenous Peyote Conservation Initiative and co-director of the RiverStyx Foundation, look for peyote, a cactus and sacred plant medicine utilized in ceremony by members of the Native American Church, in Hebbronville, Texas, Tuesday, March 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Sandor Iron Rope, Oglala Lakota tribe member, president of the Native American Church of South Dakota and Indigenous Peyote Conservation Initiative board member, looks for seeds from a peyote plant, in Hebbronville, Texas, Tuesday, March 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

Peyote growing in the wild on the 605 acres of land run by the Indigenous Peyote Conservation Initiative, which is led by several members of the Native American Church, in Hebbronville, Texas, Tuesday, March 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

A welcome sign written in several different Native American languages at the entrance to the Indigenous Peyote Conservation Initiative homesite, led by several leaders within the Native American Church, in Hebbronville, Texas, Sunday, March 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)

A peyote plant blooms while growing in the nursery at the Indigenous Peyote Conservation Initiative homesite in Hebbronville, Texas, Sunday, March 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Jessie Wardarski)