529 college savings plans are powerful tools to help pay for the mounting costs of an education. Why are some people hesitant to use them?

One common concern is oversaving. You can use 529 funds to cover only qualified education expenses without incurring a tax penalty, but it can be hard to pinpoint how much money you actually need.

Many parents open 529s for their children when they are born; they have no way of knowing whether their kids will earn a scholarship or even go to college at all. Fortunately, parents of multiple children can change the beneficiary of a 529 plan.

But what do you do if you still have money left over after covering education expenses?

Thanks to Secure 2.0, college savers won’t have to worry about overfunding their 529s. Starting this year, you can now roll over unused 529 funds to a Roth IRA. But don’t think the 529 rollover is a loophole to save extra for retirement; there are rules that limit the conversions.

Here’s what you should consider when converting your 529 funds to a Roth IRA.

The Roth IRA receiving the funds must be in the name of the 529 plan beneficiary.

The 529 plan must be open for at least 15 years.

You cannot convert 529 contributions made within the past five years (or the earnings on those contributions).

The 529 funds you roll over count toward your IRA annual contribution limit.

You can move a maximum of $35,000 from a 529 plan to a Roth IRA during your lifetime.

529 funds must be converted by paying the amount directly to a Roth IRA—you can’t pay yourself and then deposit the money into the Roth IRA later.

You can contribute to a Roth IRA only if you have earnings from a job, so the 529 beneficiary must have eligible earnings when the 529-to-IRA conversions occur.

Roth IRA income limits do not apply to 529 rollovers.

While avoiding the Roth IRA income limits is a retirement-saving perk for those with higher income, the rest of the rules around rolling over your excess 529 funds are designed to ensure that people are using 529 plans for their intended purpose: education. The annual contribution limits as well as the lifetime cap on conversions mean that you can’tdouble up on your retirement funding.

So, what’s the bottom line?

The ability to convert unused 529 funds to a Roth IRA can help alleviate potential concerns about oversaving for education. Still, don’t count on your 529 as a means to save for retirement. Instead, consider funding your Roth IRA separately.

This article was provided to The Associated Press by Morningstar. For more personal finance content, go to https://www.morningstar.com/personal-finance

Margaret Giles is a content development editor at Morningstar.

Related links:

Understand your 529 state tax benefits https://www.morningstar.com/personal-finance/how-do-your-states-529-tax-benefits-stack-up

FILE - A specialist studies monitors on the New York Stock Exchange trading floor in New York on November 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Ted Shaffrey, File)

Remember this moment because it probably won't last: A U.S. lottery jackpot soared above $1 billion, and that's still a big deal.

After three months without anyone winning the top prize, a ticket worth an estimated $1.22 billion was sold in California for the drawing Friday night. The high number evoked headlines and likely lured more people to convenience stores with dreams of private spacewalks above the Earth.

It doesn't seem to matter that the nation's top 10 jackpots, not including Friday, already boasted 10-figure payouts. For many of us, something stirs inside when a number ticks one dollar above $999,999,999.

“The question lurking is, what happens when $1 billion becomes routine and people don’t care about it anymore?” said Jonathan D. Cohen, author of the 2022 book “For a Dollar and a Dream: State Lotteries in Modern America.”

“There's no easy round number after a billion,” Cohen said. "But also, how much money can one person possibly, possibly, possibly need?”

Mega Millions ticket prices are set to rise from $2 to $5 in April. The increase will be one of many changes that officials say will result in improved jackpot odds, more frequent giant prizes and even larger payouts.

Here's brief history of lotteries and why jackpots are growing:

Cohen notes in his book that lotteries have existed in one form or another for more than 4,000 years.

In Rome, emperors and nobles held drawings at dinner parties and awarded prizes that ranged from terra cotta vases to people who were enslaved. As early as the 1400s, lotteries were used in Europe to fund city defenses and other public works.

Sweepstakes were common in the American colonies, helping to pay for the revolution against Britain. Cohen noted in his book that Thomas Jefferson approved of lotteries, writing that they were a tax “laid on the willing only.”

Lotteries began to fall out of favor in the U.S. in the 1800s because of concerns over fraud, mismanagement and impacts on poor people. But starting in the 1960s, states began to legalize them to help address financial shortfalls without raising taxes.

“Lotteries were seen as budgetary miracles, the chance for states to make revenue appear seemingly out of thin air,” Cohen wrote.

When Mega Millions started in 1996, it was called “The Big Game” and involved only six states. It was meant to compete with Powerball, which then had 20 states and the District of Columbia.

The original payout for The Big Game started at $5 million. The value would be nearly twice that today accounting for inflation.

In 2024 dollars, the before-taxes prize could buy a rare copy of the U.S. Constitution or cover Michael Soroka's $9 million contract to pitch next season for the Washington Nationals.

By contrast, the pre-tax winnings from Friday’s Mega Millions prize could theoretically buy a Major League Baseball team. The Nationals would be too expensive. But Forbes recently valued the Miami Marlins at $1 billion.

A better comparison might be Taylor Swift's tour revenue at the end of 2023. Her Eras Tour became the first to earn more than $1 billion after selling more than 4 million tickets.

Swift, however, was expected to bring in a total of more than $2 billion when her tour finally wrapped up Dec. 8, according to concert trade publication Pollstar.

These days, Mega Millions and its lottery compatriot Powerball are sold in 45 states, as well as Washington, D.C., and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Powerball also is sold in Puerto Rico.

In October, Mega Millions said it hoped increased ticket revenue and less stratospheric odds would lead to more people winning, even as prizes grow extraordinarily high.

Games with massive payouts tend to be more popular despite the slimmer odds. Larger jackpots also attract more media attention, increase ticket sales and bring in new players, Cohen said.

Lottery officials have allowed the odds to become lower with a larger pool of numbers to pick from, Cohen said. And that has made games harder to win, leading to payouts rolling over into even larger prizes.

The first $1 billion jackpot was in 2016. Cohen said he expects the upward trajectory to continue.

Meanwhile, he warned against the tropes of the troubled or bankrupt lottery winner.

A well-known example is Andrew “Jack” Whittaker Jr. He won a record Powerball jackpot after buying a single ticket in 2002 but quickly fell victim to scandals, lawsuits and personal setbacks as he endured constant requests for money, leaving him unable to trust others.

Most winners don't turn out like him, Cohen said.

“Even if we deny it, we all sort of believe in the meritocracy — this belief that if you won your money through luck, then you probably didn’t actually deserve it,” Cohen said. And yet various studies have shown “lottery winners are happier, healthier and wealthier than the rest of us.”

A digital Mega Millions ticket is seen on a screen as a person makes their selections on a self-serve terminal inside a gas station ahead of Friday's Mega Millions drawing of $1.15 billion, Thursday, Dec. 26, 2024, in Baltimore. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

A person makes their lottery ticket selections on a self-serve terminal inside a gas station ahead of Friday's Mega Millions drawing of $1.15 billion, Thursday, Dec. 26, 2024, in Baltimore. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

A person retrieves a Mega Millions lottery ticket from a self-serve terminal ahead of Friday's Mega Millions drawing of $1.15 billion, Thursday, Dec. 26, 2024, in Baltimore. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

A person inserts cash into a self-serve terminal while holding their play slip ahead of Friday's Mega Millions drawing of $1.15 billion, Thursday, Dec. 26, 2024, in Baltimore. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Rob holds up a Mega Millions ticket at Rossi's Deli in San Francisco, Thursday, Dec. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu)

A person fills out a Mega Millions play slip ahead of Friday's Mega Millions drawing of $1.15 billion, Thursday, Dec. 26, 2024, in Baltimore. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Rob, right, buys a Mega Millions ticket at Rossi's Deli in San Francisco, Thursday, Dec. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu)

Rina Flores, middle, works behind the counter over a sign advertising the estimated $1.15 billion Mega Millions jackpot, bottom right, at Rossi's Deli in San Francisco, Thursday, Dec. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu)

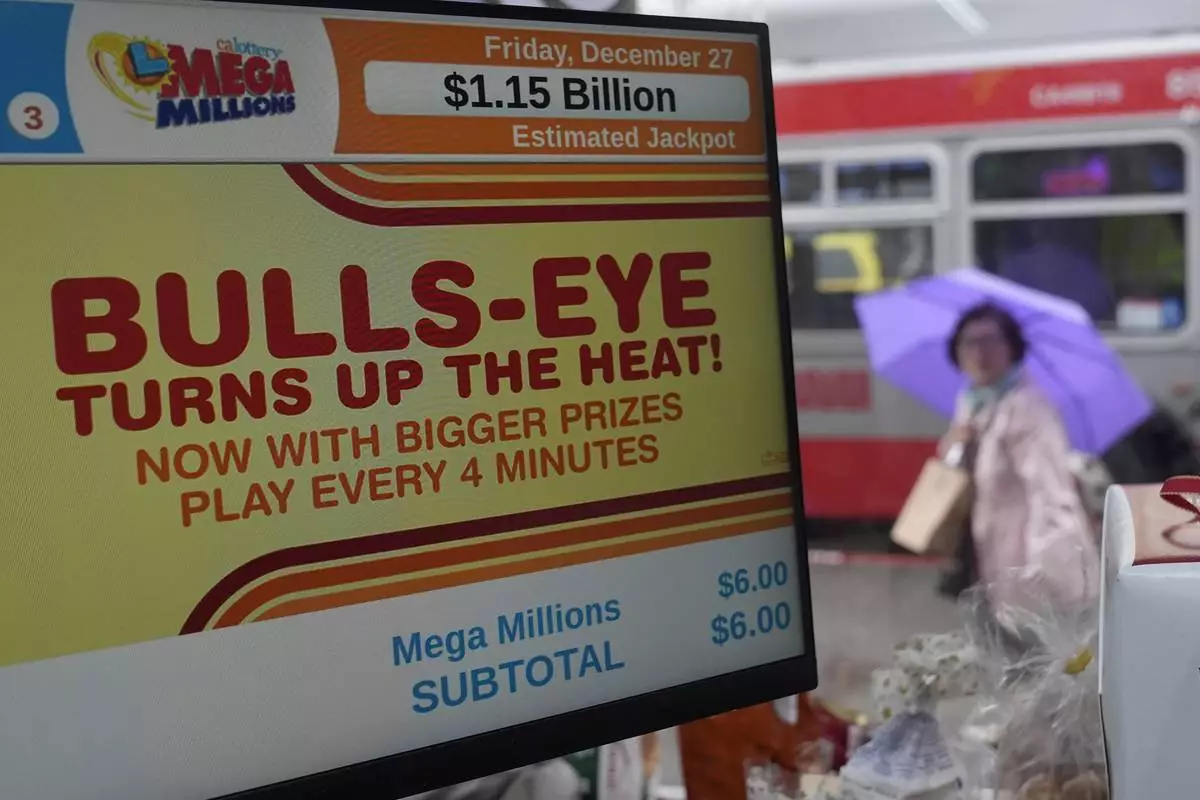

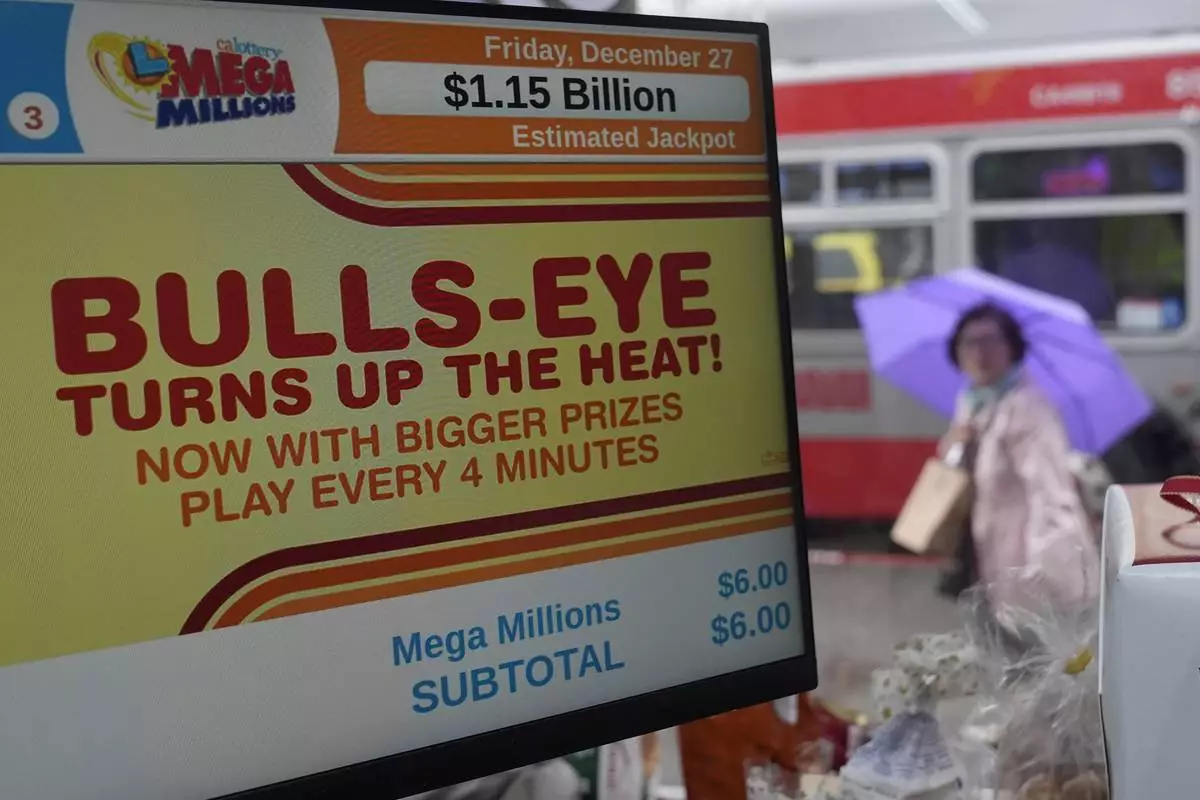

A pedestrian walks behind a sign advertising the estimated $1.15 billion Mega Millions jackpot at Rossi's Deli in San Francisco, Thursday, Dec. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu)

Oscar Flores, left, works behind the counter next to a sign advertising the estimated $1.15 billion Mega Millions jackpot at Rossi's Deli in San Francisco, Thursday, Dec. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu)

A Mega Millions lottery ticket is displayed at a store on Thursday, Dec. 26, 2024, in Tigard, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

Fidel Lule buys a MegaMillion lottery ticket at Won Won Mini Mart in Chinatown Los Angeles, Thursday, Dec. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes)

The option to play the $1.15 billion Mega Millions jackpot is seen on a self-serve terminal inside a gas station in Baltimore, Thursday, Dec. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)