SAO PAULO (AP) — Brazilian-made dramas rarely last long in local cinemas. But, nearly two months after its release, “I’m Still Here,” a film about a family torn apart by the military dictatorship that ruled Brazil for more than two decades, has drawn millions of moviegoers across the South American country.

The film's domestic box office success — with nearly 3 million tickets sold, it secured the fifth spot at the 2024 box office by mid December — is rooted in its exploration of a long-neglected national trauma, but it is particularly timely, especially as Brazil confronts a recent near-miss with democratic rupture.

Set in the 1970s and based on true events, “I’m Still Here” tells the story of the Paivas, an upper-class family in Rio de Janeiro shattered by the dictatorship. Rubens Paiva, a former leftist congressman, was taken into custody by the military in 1971 and was never seen again. The narrative centers on his wife, Eunice Paiva, and her lifelong pursuit of justice.

The film was nominated for a Golden Globe for best foreign language film and shortlisted for the Oscars in the same category.

“Comedies and other topics are more likely to become mega-successes, but this (the dictatorship) is a very taboo subject for us,” said Brazilian psychoanalyst and writer Vera Iaconelli, adding that she felt a “sense of urgency” after watching the movie last month, even though the dictatorship ended almost four decades ago.

As the movie was being shown across Brazil, the Federal Police unsealed a report detailing a 2022 plot by military officers to stage a coup to prevent President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva from taking office, and to keep far-right former army captain Jair Bolsonaro in power. Bolsonaro and his allies have denied any involvement in participating or inciting a coup.

“Even if (director) Walter Salles wanted to plan the timing of the release this precisely, he wouldn’t have gotten it so right,” said Lucas Pedretti, a historian and sociologist whose works address memory and reparations after the military dictatorship.

“The film plays a very important role in telling us: ‘Look, this is what would happen if the coup that was planned by Bolsonaro and his military officers had succeeded.’”

Unlike countries like Argentina and Chile, which established truth commissions and prosecuted former dictators and their henchmen, Brazil's transition back to democracy was marked by a sweeping amnesty to military officials.

For years, said Pedretti, Brazil’s military promoted the notion that government silence was the best way to bury the past.

It was not until 2011 that Brazil’s then- President Dilma Rousseff — a former guerrilla who was tortured during the dictatorship — established a national truth commission to investigate its abuses.

The commission's 2014 report detailed harrowing accounts of torture and named perpetrators of human rights violations — none were ever imprisoned. But just as a reckoning of the dictatorship began, calls for a return to military rule emerged in street protests against corruption revelations.

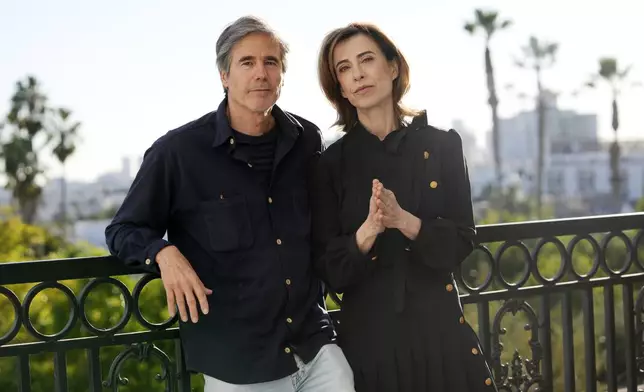

It was then that Marcelo Rubens Paiva, one of Rubens' sons, decided to share his family's story in his 2015 book “I'm Still Here." The book introduced Eunice Paiva to a larger audience, chronicling her journey from a housewife to a relentless advocate for her disappeared husband, and how she raised five children by herself, while also pursuing a law degree.

In the years that followed, far-right, anti-establishment forces increasingly gained traction. Bolsonaro — who has long celebrated the coup and praised dictatorship-era torturers — would go on to ride that wave to a presidential victory in 2018.

Observing the surge of the far-right in Brazil, filmmaker Salles realized the country's memory of its dictatorship was very fragile. He said he saw a need for his country to confront its trauma in order to prevent history from repeating itself.

“I’m Still Here” isn’t the first Brazilian movie to explore the memory of the dictatorship, but it is the most popular. Unlike other films on the subject that tend to focus on dissidents and armed resistance, Salles chose to frame his as a family drama and how the disappearance of the family patriarch upended their day-to-day lives.

Its climax — spoiler alert! — arrives 25 years after Rubens’ disappearance, when Eunice finally receives his death certificate.

In December, a month after the film’s premiere, the Brazilian government allowed families of dictatorship-era victims to obtain reissued death certificates acknowledging state-sponsored killings.

"It is very symbolic that this is happening amid the international repercussion of ‘I’m Still Here’ ... so younger people can understand a bit of what that period was like,” Brazil's Human Rights Minister Macaé Evaristo said during the announcement, calling it an important step in the “healing process for Brazilian society.”

The healing process remains incomplete, as some forces — once again — seek to prevent those who allegedly sought to sabotage democracy from being held to account.

On Nov. 29, Bolsonaro urged Lula and the Supreme Court to grant amnesty for those involved in the 2022 alleged coup plot and, alongside his allies, pushed for legislation to pardon participants in the 2023 anti-democratic riot that aimed to oust Lula and marked an echo of the Capitol insurrection in the U.S.

“The coup is still here. It’s still in people’s minds, it’s still in the minds of the military,” said Paulo Sergio Almeida, a filmmaker and founder of Filme B, a company that tracks Brazil's national cinema. “We thought this was a thing of the past, but it’s not. The past is still present in Brazil.”

This time around, many Brazilians are calling for the prosecution of those responsible for the attempted coup, believing that justice is essential for national reconciliation and future progress.

On Dec. 14, police arrested Bolsonaro's 2022 running mate and former defense minister in connection with investigations into the alleged coup plot, becoming the first four-star general arrested by civilians since the end of the dictatorship in 1985.

“It's a sign that we are making progress as a constitutional democracy,” leftist Sen. Randolfe Rodrigues wrote on X that day. “Brazil still has a long way to go as a Republic, but today is a HISTORIC day on this journey.”

Brazilians have also embraced the “No amnesty!" rallying cry, which originated at street protests in the aftermath of the capital's 2023 riot and can still be heard.

Earlier this month, a Supreme Court justice cited “I’m Still Here” while arguing that the 1979 amnesty law shouldn’t apply to the crime of concealing bodies.

“The disappearance of Rubens Paiva, whose body was never found or buried, highlights the enduring pain of thousands of families,” Justice Flávio Dino said.

Striking a chord in Brazil was precisely Marcelo Rubens Paiva's intent when adapting his book into a film.

“The movie is sparking this debate, and it arrived at the right moment for people to recognize that living under a dictatorship is no longer acceptable,” he said.

On a recent evening in Sao Paulo, 46-year-old Juliana Patrícia and her 16-year-old daughter, Ana Júlia, left a movie theater in tears, touched by “I’m Still Here.”

“We saw all the suffering that Eunice endured, with Rubens being killed and taken from his family in such a brutal way,” Patrícia said. “It made us even more certain that democracy needs to be respected and that, as Brazilians, we must fight harder to ensure that this never happens in our country again.”

Follow AP’s coverage of Latin America and the Caribbean at https://apnews.com/hub/latin-america

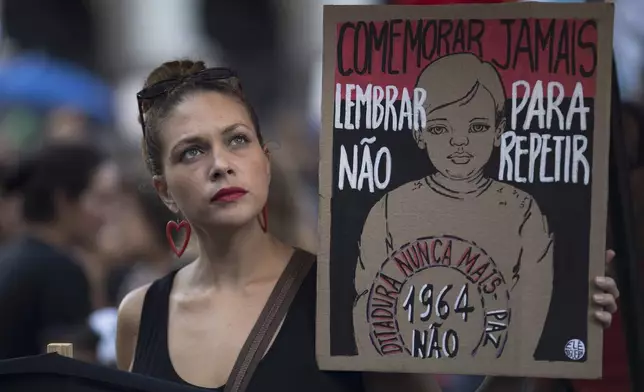

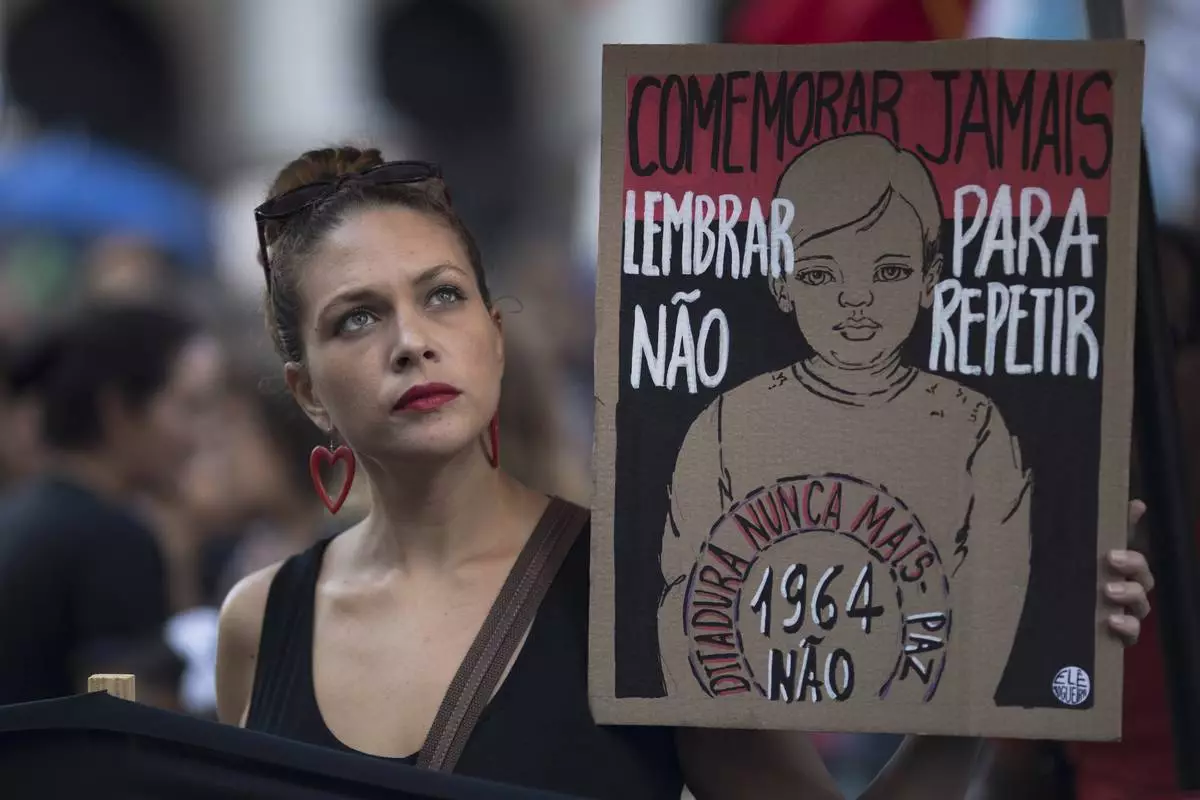

FILE - A demonstrator holds a sign that reads in Portuguese "Never commemorate. Remember in order to not repeat. Dictatorship never again," during a protest against Brazil's 1964 military coup, in Rio de Janeiro, March 31, 2019. (AP Photo/Leo Correa, File)

FILE - With a mask hanging in the foreground, demonstrators perform as victims in a torture device called pau-de-arara, or parrot's perch, during a demonstration organized by the Rio de Paz NGO to remember the victims of Brazil's military dictatorship, on Copacabana beach in Rio de Janeiro, Dec. 10, 2019. (AP Photo/Silvia Izquierdo, File)

Writer Marcelo Rubens Paiva, the author of the book that served as the basis for the film "I'm Still Here," poses for a photo during an interview in Sao Paulo, Friday, Dec. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Andre Penner)

FILE - Armed forces take part in a ceremony to commemorate the 1964 military coup that began the last Brazilian dictatorship, in Sao Paulo, Brazil, March 28, 2019. (AP Photo/Andre Penner, File)

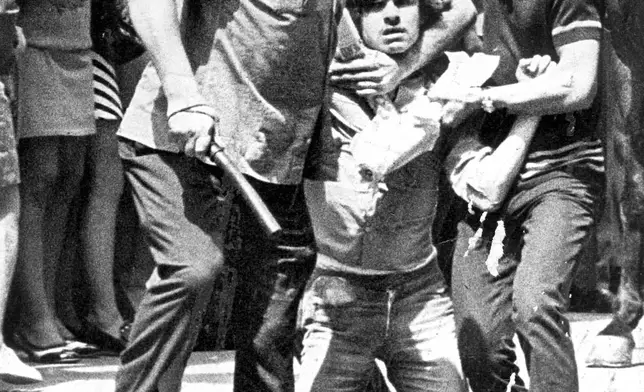

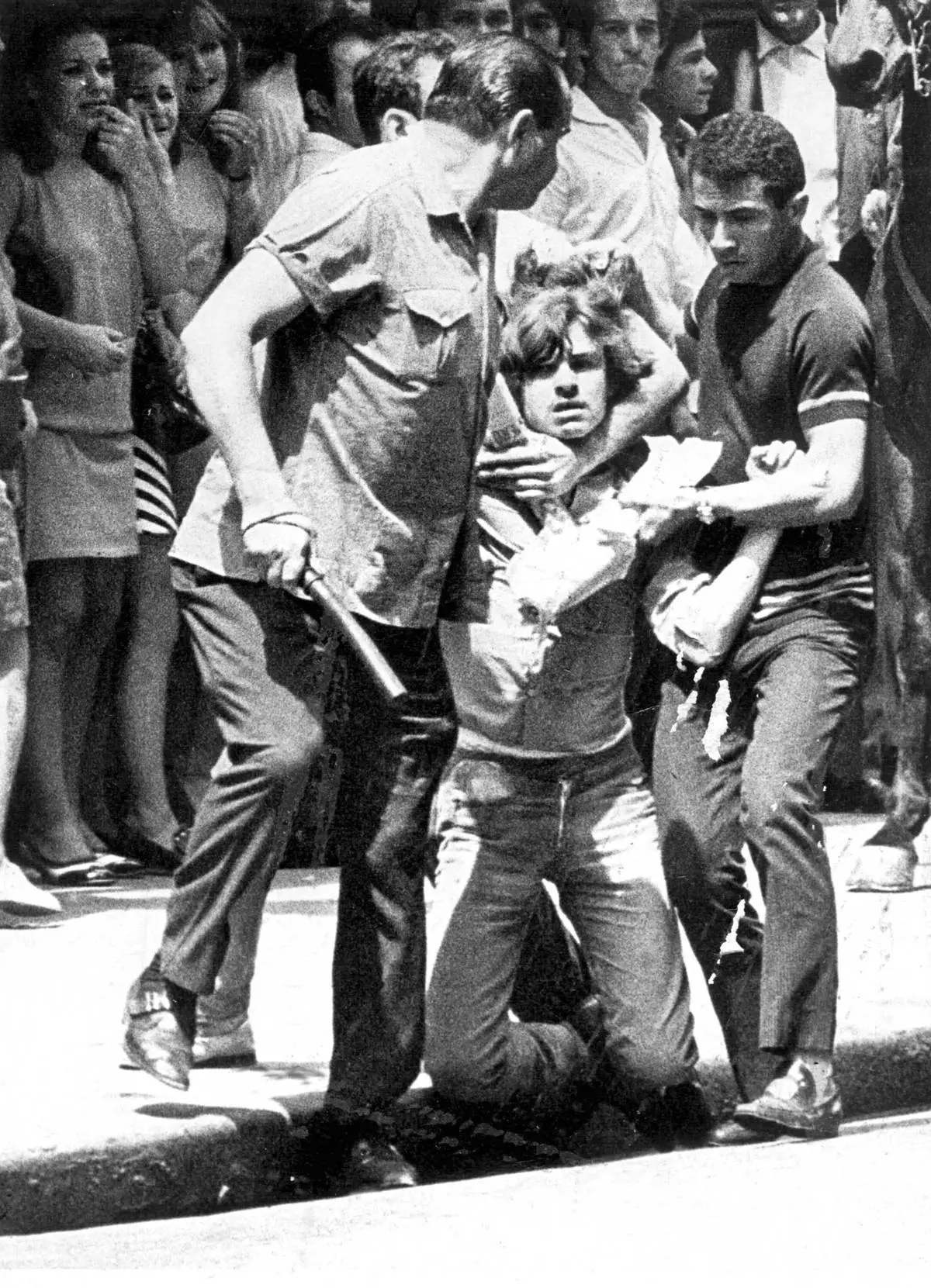

FILE - Unidentified men detain a student during a protest in Sao Paulo, Oct. 9, 1968. (AP Photo/Agencia Estado, File)

FILE - Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, left, and Defense Minister Walter Braga Netto attend a ceremony honoring military athletes who participated in the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games at the military's Admiral Adalberto Nunes Physical Education Center in Rio de Janeiro, Sept. 1, 2021. (AP Photo/Silvia Izquierdo, File)

FILE - Police gather on the other side of a window that was shattered by supporters of former President Jair Bolsonaro who stormed the Planalto Palace in Brasilia, Brazil, Jan. 8, 2023. (AP Photo/Eraldo Peres, File)

FILE - Walter Salles, left, director of the film "I'm Still Here," and cast member Fernanda Torres pose for a portrait to promote the film, Nov. 13, 2024, in West Hollywood, Calif. (AP Photo/Chris Pizzello, File)

People wait to watch the film "I'm Still Here," at a movie theater in Sao Paulo, Friday, Dec. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Andre Penner)

FILE - Demonstrators hold photos of people who were killed in Brazil's dictatorship, during the "Walk of Silence" march in memory of the victims, marking the anniversary of the country's 1964 coup, in Sao Paulo, April 2, 2023. (AP Photo/Andre Penner, File)