BORMIO, Italy (AP) — The weekend’s ski racing in Bormio showed precisely why the men’s downhill for the 2026 Olympics will be one of the toughest in the past 30 years.

American skier Bryce Bennett says he has “trauma” from racing down the fearsome Stelvio slope, while Italian veteran Christof Innerhofer — who has competed at four Olympics — can’t remember a tougher course.

Click to Gallery

Italy's Christof Innerhofer speeds down the course during an alpine ski, men's World Cup downhill race, in Bormio, Italy, Saturday, Dec. 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Gabriele Facciotti)

Emergencies helicopter takes Switzerland's Gino Caviezel to the hospital after his fall during an alpine ski, men's World Cup Super G race, in Bormio, Italy, Sunday, Dec. 29, 2024. (AP Photo/Marco Trovati)

Switzerland's Marco Odermatt is airborn during an alpine ski, men's World Cup downhill training, in Bormio, Italy, Friday, Dec. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Gabriele Facciotti)

Austria's Daniel Hemetsberger speeds down the course during an alpine ski, men's World Cup downhill training, in Bormio, Italy, Friday, Dec. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Gabriele Facciotti)

Switzerland's Marco Odermatt speeds down the course during an alpine ski, men's World Cup Super G race, in Bormio, Italy, Sunday, Dec. 29, 2024. (AP Photo/Gabriele Facciotti)

Medical staff are helping France's Cyprien Sarrazin after crashing into protections net during an alpine ski, men's World Cup downhill training, in Bormio, Italy, Friday, Dec. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Alessandro Trovati)

Medical staff are carrying France's Cyprien Sarrazin after crashing into protections net during an alpine ski, men's World Cup downhill training, in Bormio, Italy, Friday, Dec. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Alessandro Trovati)

France's Cyprien Sarrazin is airborn during an alpine ski, men's World Cup downhill training, in Bormio, Italy, Friday, Dec. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Gabriele Facciotti)

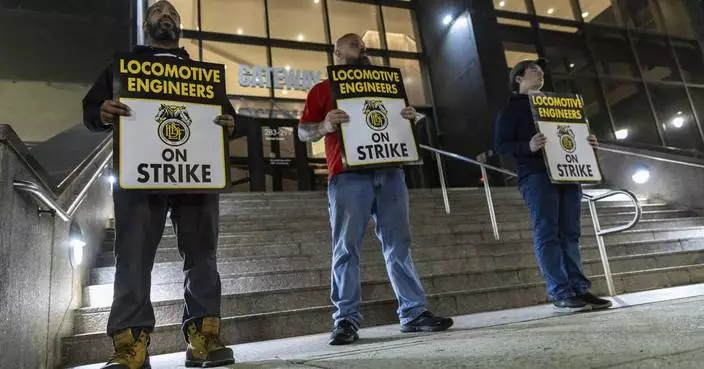

The difficulty was highlighted by a number of crashes during the World Cup weekend and three skiers had to be airlifted to a hospital — including French standout Cyprien Sarrazin, who needed surgery to drain bleeding on the brain.

The Milan-Cortina Olympics will see the Games return to Europe after the three previous editions were held in Russia, South Korea and China. The men’s Alpine skiing events will take place in Bormio, while the women’s will be held in Cortina d’Ampezzo. The two ski areas are separated by a five-hour car ride.

“For sure will be special because the last Olympic Games was far away from here,” said the 40-year-old Innerhofer, who won silver and bronze in the downhill and combined, respectively, in Sochi in 2014.

“In the past 12 or 16 years you’ve had some really tough slope like Sochi, some easier slope like Korea, some medium slope like China. But this one will be a tough one. This will be the toughest one I think for the last 30 years.”

Unrelenting, knee-rattling, complicated by shaded sections and producing speeds touching 140 kph (87 mph), the Stelvio is a notoriously unforgiving track.

“Here it’s really the limit,” Innerhofer said. “Nobody can imagine how difficult to ski down: with the light, with the speed, with the bumps, with the jumps.”

It is one of the most physically demanding on the circuit, at almost 3,230 meters long with a 986-meter vertical drop and a maximum gradient of 63%.

“I remember growing up and like, old guys would just not come here. And now I get older and I … get it,” said the 32-year-old Bennett, who finished fourth in a downhill in 2018 in Bormio, but hasn’t finished inside the top 30 on the Stelvio since.

“It’s like I just have had such bad feelings here the last three years and I haven’t quite been able to shake it. I would call it like trauma almost a little bit. And so I’m trying to work through it. It’s like you got to take risk in the right way and be confident in the skiing and the feeling and it’s just hard to find here for me at the moment.”

The downhill is an event so speedy and dangerous to begin with that it’s the only one where athletes usually are given two opportunities to take practice runs before a race.

It was on Friday's second training run that Sarrazin had his crash, leading his teammate Nils Allègre to lambast organizers, saying “they don’t know how to prepare a course.”

He even went as far as to add “they don’t deserve to have the Olympic Games here.”

Race director Omar Galli refuted those claims and highlighted that the organizers have “significantly upgraded safety features” and will further enhance those for the Olympics.

Three-time defending overall champion Marco Odermatt was more diplomatic about the difficulties of the slope.

“The Stelvio is like a constant fight for survival,” the reigning downhill champion said. “The big problem: 80% of the course is completely icy; 20% consists of aggressive snow.

“This irregularity makes it difficult to do the right thing with the skis. Yes, it is a fight for survival from start to finish.”

The major advantage the Olympics will have over the World Cup is that the events in Bormio will take place in February and not in December.

That will help with the uniformity of the slope and, more importantly, the notoriously dark Stelvio piste will be mostly in the sun.

The last time it was raced in February was at the 2005 world championships, where the downhill finished in an American one-two after Daron Rahlves finished runner-up to Bode Miller.

“I am excited to ski this in the sun,” Bennett said. “It’s so dark. So having a little bit of light on the course, I think it will be fun to ski and I’ve heard that from former athletes, like Bode and Daron. They’re like ‘it’s easy in the sun!’ I don’t think it’s easy, but it’s easier than it is.”

AP sports: https://apnews.com/sports

Italy's Christof Innerhofer speeds down the course during an alpine ski, men's World Cup downhill race, in Bormio, Italy, Saturday, Dec. 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Gabriele Facciotti)

Emergencies helicopter takes Switzerland's Gino Caviezel to the hospital after his fall during an alpine ski, men's World Cup Super G race, in Bormio, Italy, Sunday, Dec. 29, 2024. (AP Photo/Marco Trovati)

Switzerland's Marco Odermatt is airborn during an alpine ski, men's World Cup downhill training, in Bormio, Italy, Friday, Dec. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Gabriele Facciotti)

Austria's Daniel Hemetsberger speeds down the course during an alpine ski, men's World Cup downhill training, in Bormio, Italy, Friday, Dec. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Gabriele Facciotti)

Switzerland's Marco Odermatt speeds down the course during an alpine ski, men's World Cup Super G race, in Bormio, Italy, Sunday, Dec. 29, 2024. (AP Photo/Gabriele Facciotti)

Medical staff are helping France's Cyprien Sarrazin after crashing into protections net during an alpine ski, men's World Cup downhill training, in Bormio, Italy, Friday, Dec. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Alessandro Trovati)

Medical staff are carrying France's Cyprien Sarrazin after crashing into protections net during an alpine ski, men's World Cup downhill training, in Bormio, Italy, Friday, Dec. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Alessandro Trovati)

France's Cyprien Sarrazin is airborn during an alpine ski, men's World Cup downhill training, in Bormio, Italy, Friday, Dec. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Gabriele Facciotti)

It's the tweet that changed everything for Oscar Piastri.

A blunt 48-word message in 2022 paved the way for the Australian driver to lead the current Formula 1 standings with McLaren, rather than struggling to get into the top 10 with Alpine.

“I understand that, without my agreement, Alpine F1 have put out a press release late this afternoon that I am driving for them next year,” Piastri wrote. “This is wrong and I have not signed a contract with Alpine for 2023. I will not be driving for Alpine next year.”

Nearly three years on from Piastri — who was then Alpine's reserve — snubbing the team for McLaren in such a public way, it's clear he made the right choice.

Piastri has won four of the six races this season and is on a streak of three wins in a row. He has 131 points this year, while Alpine has seven points in total and last won a race nearly four years ago.

Piastri is targeting a fourth consecutive win in the Emilia-Romagna Grand Prix on Sunday, but suspects the bumpy Imola track could mean tougher competition for McLaren than two weeks ago in Miami.

“When you’ve won four out of six, it’s been a great start. I’ve been enjoying the success we’ve been having on track, but for me what’s been very satisfying is all the work we’ve done behind the scenes to achieve that,” he said Thursday. “It’s quite a different feeling when you win a race because you feel like you’ve just gotten by or had good circumstances. But to now be winning because we have an incredibly quick car and I feel like I’m driving well, that’s very satisfying.”

Piastri and McLaren had the pace again in Friday’s first practice session as the Australian was fastest by .0032 of a second ahead of teammate and title rival Lando Norris. Carlos Sainz, Jr. was third-fastest for Williams, .020 off Norris’ time. Defending champion Max Verstappen was only seventh-fastest for Red Bull.

The session was stopped with just over two minutes left when Gabriel Bortoleto slid off track and tapped the barrier, leaving his Sauber stuck in the gravel.

Alpine isn't challenging the top teams on pace but it's in pole position for drama.

The Renault-owned team had been expected for months to drop Australian driver Jack Doohan, a rookie, for the fast but inconsistent reserve Franco Colapinto.

At the Miami Grand Prix, team principal Oliver Oakes dismissed that claim, but two days after the Miami race, Oakes suddenly resigned. A day later, Alpine dropped Doohan — whose best race result was 13th — after the Miami Grand Prix and promoted Colapinto.

The Argentine driver, a mid-season replacement at Williams in 2024, is happy to be back in F1 but expressed reservations Thursday about how the whole process has been handled.

Colapinto said it's “never nice circumstances” to get a seat at another driver's expense, and expressed concern his new deal — which only runs for five races — isn't long enough to really show what he can do.

The first of two races in Italy this year is already delighting the home fans.

For the first time since 2021, they have an Italian driver in Mercedes' 18-year-old Kimi Antonelli, and Ferrari's red-clad tifosi fans get their first sight of Lewis Hamilton racing for the team on Italian soil.

Piastri, too, has been connecting with his Italian heritage as he met with some “very, very distant relatives” and became an honorary citizen of Licciana Nardi in Tuscany, where his family name originated.

AP auto racing: https://apnews.com/hub/auto-racing

Alpine driver Franco Colapinto of Argentina steers his car during the first free practice at the Enzo and Dino Ferrari racetrack, ahead the Italy's Emilia Romagna Formula One Grand Prix, in Imola, Italy, Friday, May 16, 2025. (AP Photo/Luca Bruno)

McLaren driver Oscar Piastri of Australia steers his car during the first free practice at the Enzo and Dino Ferrari racetrack, ahead the Italy's Emilia Romagna Formula One Grand Prix, in Imola, Italy, Friday, May 16, 2025. (AP Photo/Luca Bruno)

McLaren driver Oscar Piastri of Australia sits in his car during the first free practice at the Enzo and Dino Ferrari racetrack, ahead the Italy's Emilia Romagna Formula One Grand Prix, in Imola, Italy, Friday, May 16, 2025. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

McLaren driver Oscar Piastri of Australia walks in the paddock at the Dino and Enzo Ferrari racetrack, ahead the Italy's Emilia Romagna Formula One Grand Prix in Imola, Italy, Thursday, May 15, 2025. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

McLaren driver Lando Norris of Britain, left, is flaked by his teammate Oscar Piastri of Australia in the paddock at the Dino and Enzo Ferrari racetrack, ahead the Italy's Emilia Romagna Formula One Grand Prix in Imola, Italy, Thursday, May 15, 2025. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

McLaren driver Oscar Piastri of Australia answers reporters during a news conference at the Enzo and Dino Ferrari racetrack, ahead the Italy's Emilia Romagna Formula One Grand Prix in Imola, Italy, Thursday, May 15, 2025. (AP Photo/Luca Bruno)