SAN FRANCISCO--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Jan 1, 2025--

Sephora is kicking off the new year by unveiling its highly anticipated lineup of 2025 birthday gift offerings for the U.S. and Canada and there is so much to look forward to!

This press release features multimedia. View the full release here: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20250101558566/en/

The gifts can be redeemed for free at Sephora and Sephora at Kohl’s locations, or online with a $25 minimum purchase**.

“Our annual birthday gifts are such a special and celebratory moment for our more than 40 million Beauty Insider Members and this year we have even more coveted offerings shoppers can choose from," said Emeline Berlind, Senior Vice President and General Manager, Loyalty at Sephora. "This year, we are offering our biggest selection ever – filled with curated gifts across every category at Sephora for customers to pick what best suits their needs and routines. This is truly a unique-to-Sephora experience, and we love that we’re able to show our appreciation to our amazing Beauty Insider members every year!”

Explore the 2025 Core Birthday Gift Lineup:

The first online-exclusive rotating gift reserved for VIB and Rouge members:

Join the celebration today! Become a Beauty Insider Member for free by signing up in-store, on Sephora.com, or on the Sephora app. Please see terms and conditions here for eligibility.

* Not available at Sephora at Kohl’s or Kohls.com

**Customers can redeem their Birthday Gift for free in store or by spending a minimum of $25 at sephora.com or sephora.ca. No minimum purchase required to redeem at Sephora at Kohl’s or on kohls.com.

About Sephora Americas

Sephora is the world’s leading global prestige beauty retail brand. With 52 000 passionate employees operating in 34 markets, Sephora connects customers and beauty brands within the world’s most trusted and dynamic beauty community. We serve a highly engaged community of hundreds of millions of beauty followers across our global omnichannel network of more than 3 000 stores and iconic flagships, and our e-commerce and digital platforms, offering personalized and immersive seamless experiences across every touchpoint. With our curation of close to 500 brands and our own label, Sephora Collection, we offer the most unique and diverse range of prestige beauty products, tailored to our customers’ needs from fragrance to make-up, haircare, skincare and beyond, as we constantly reimagine the world of prestige beauty.

Since our inception in 1969 in Limoges, France, and as part of the LVMH Group since 1997, we have been disrupting the prestige beauty retail industry. Today, we continue to break with convention to drive our mission: champion a world of inspiration and inclusion where everyone can celebrate their beauty.

Photo courtesy of Sephora

WASHINGTON (AP) — When the Justice Department lifted a school desegregation order in Louisiana this week, officials called its continued existence a “historical wrong” and suggested that others dating to the Civil Rights Movement should be reconsidered.

The end of the 1966 legal agreement with Plaquemines Parish schools announced Tuesday shows the Trump administration is “getting America refocused on our bright future,” Assistant Attorney General Harmeet Dhillon said.

Inside the Justice Department, officials appointed by President Donald Trump have expressed desire to withdraw from other desegregation orders they see as an unnecessary burden on schools, according to a person familiar with the issue who was granted anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly.

Dozens of school districts across the South remain under court-enforced agreements dictating steps to work toward integration, decades after the Supreme Court struck down racial segregation in education. Some see the court orders' endurance as a sign the government never eradicated segregation, while officials in Louisiana and at some schools see the orders as bygone relics that should be wiped away.

The Justice Department opened a wave of cases in the 1960s, after Congress unleashed the department to go after schools that resisted desegregation. Known as consent decrees, the orders can be lifted when districts prove they have eliminated segregation and its legacy.

The Trump administration called the Plaquemines case an example of administrative neglect. The district in the Mississippi River Delta Basin in southeast Louisiana was found to have integrated in 1975, but the case was to stay under the court’s watch for another year. The judge died the same year, and the court record “appears to be lost to time,” according to a court filing.

“Given that this case has been stayed for a half-century with zero action by the court, the parties or any third-party, the parties are satisfied that the United States’ claims have been fully resolved,” according to a joint filing from the Justice Department and the office of Louisiana Attorney General Liz Murrill.

Plaquemines Superintendent Shelley Ritz said Justice Department officials still visited every year as recently as 2023 and requested data on topics including hiring and discipline. She said the paperwork was a burden for her district of fewer than 4,000 students.

“It was hours of compiling the data,” she said.

Louisiana “got its act together decades ago,” said Leo Terrell, senior counsel to the Civil Rights Division at the Justice Department, in a statement. He said the dismissal corrects a historical wrong, adding it’s “past time to acknowledge how far we have come.”

Murrill asked the Justice Department to close other school orders in her state. In a statement, she vowed to work with Louisiana schools to help them “put the past in the past.”

Civil rights activists say that's the wrong move. Many orders have been only loosely enforced in recent decades, but that doesn't mean problems are solved, said Johnathan Smith, who worked in the Justice Department's Civil Rights Division during President Joe Biden's administration.

“It probably means the opposite — that the school district remains segregated. And in fact, most of these districts are now more segregated today than they were in 1954," said Smith, who is now chief of staff and general counsel for the National Center for Youth Law.

More than 130 school systems are under Justice Department desegregation orders, according to records in a court filing this year. The vast majority are in Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi, with smaller numbers in states like Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina. Some other districts remain under separate desegregation agreements with the Education Department.

The orders can include a range of remedies, from busing requirements to district policies allowing students in predominately Black schools to transfer to predominately white ones. The agreements are between the school district and the U.S. government, but other parties can ask the court to intervene when signs of segregation resurface.

In 2020, the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund invoked a consent decree in Alabama’s Leeds school district when it stopped offering school meals during the COVID-19 pandemic. The civil rights group said it disproportionately hurt Black students, in violation of the desegregation order. The district agreed to resume meals.

Last year, a Louisiana school board closed a predominately Black elementary school near a petrochemical facility after the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund said it disproportionately exposed Black students to health risks. The board made the decision after the group filed a motion invoking a decades-old desegregation order at St. John the Baptist Parish.

The dismissal has raised alarms among some who fear it could undo decades of progress. Research on districts released from orders has found that many saw greater increases in racial segregation compared with those under court orders.

“In very many cases, schools quite rapidly resegregate, and there are new civil rights concerns for students,” said Halley Potter, a senior fellow at The Century Foundation who studies educational inequity.

Ending the orders would send a signal that desegregation is no longer a priority, said Robert Westley, a professor of antidiscrimination law at Tulane University Law School in New Orleans.

“It’s really just signaling that the backsliding that has started some time ago is complete," Westley said. “The United States government doesn’t really care anymore of dealing with problems of racial discrimination in the schools. It’s over.”

Any attempt to drop further cases would face heavy opposition in court, said Raymond Pierce, president and CEO of the Southern Education Foundation.

“It represents a disregard for education opportunities for a large section of America. It represents a disregard for America’s need to have an educated workforce," he said. “And it represents a disregard for the rule of law.”

Associated Press writer Sharon Lurye contributed from New Orleans.

This story has been corrected to reflect the group that invoked desegregation orders in other Louisiana districts is the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, not the NAACP.

The Associated Press’ education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

FILE - Louisiana Attorney General Liz Murrill speaks to reporters, Jan. 1, 2025, in New Orleans. (AP Photo/Matthew Hinton, file)

FILE - Children smile from window of a school bus in Springfield, Mass., as court-ordered busing brought Black children and white children together in elementary grades without incident, Sept. 16, 1974. (AP Photo/Peter Bregg, File)

FILE - White and Black children mix freely on the playground outside a school in a racially mixed neighborhood, Oct. 18, 1957, in Detroit. (AP Photo/Alvan Quinn, File)

FILE - Students from Charlotte High School in Charlotte, N.C., ride a bus together, May 15, 1972. (AP Photo/Harold L. Valentine, File)

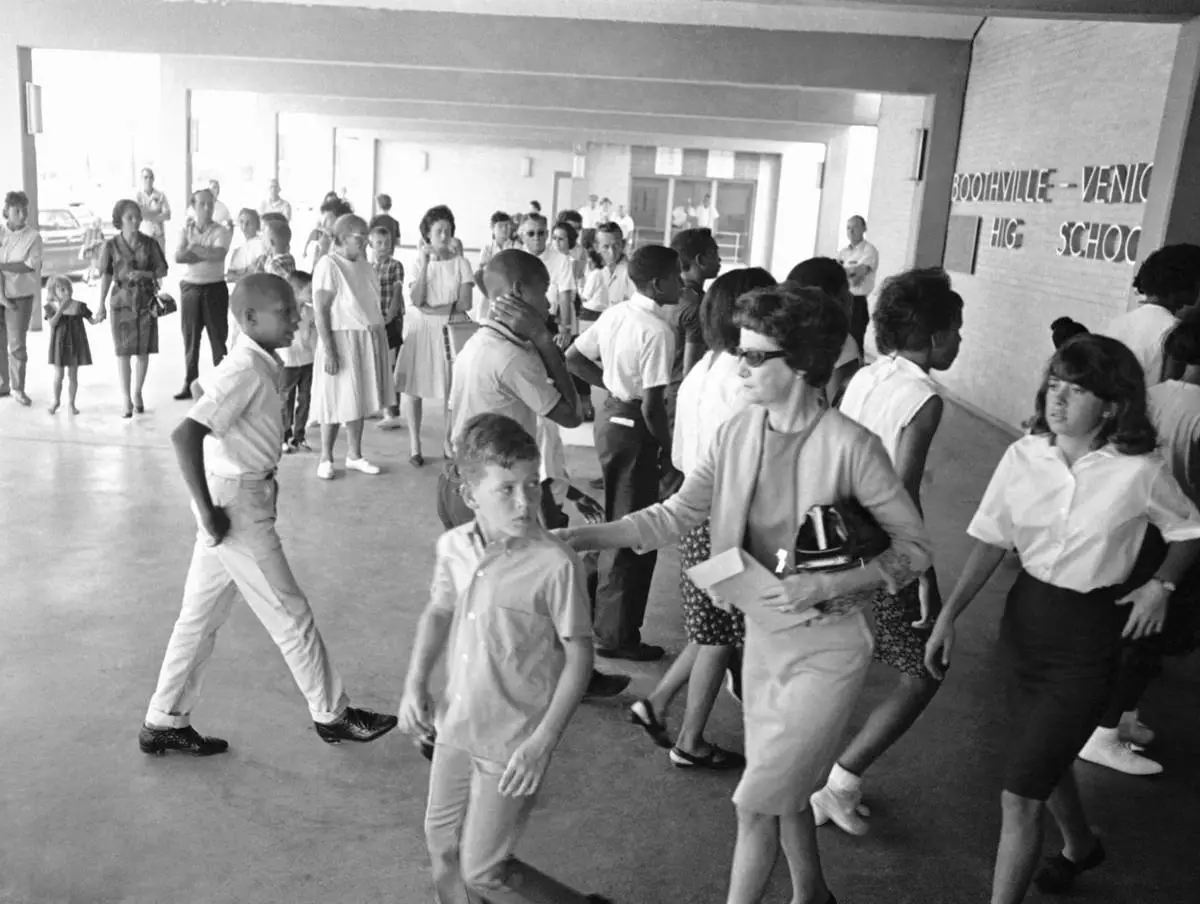

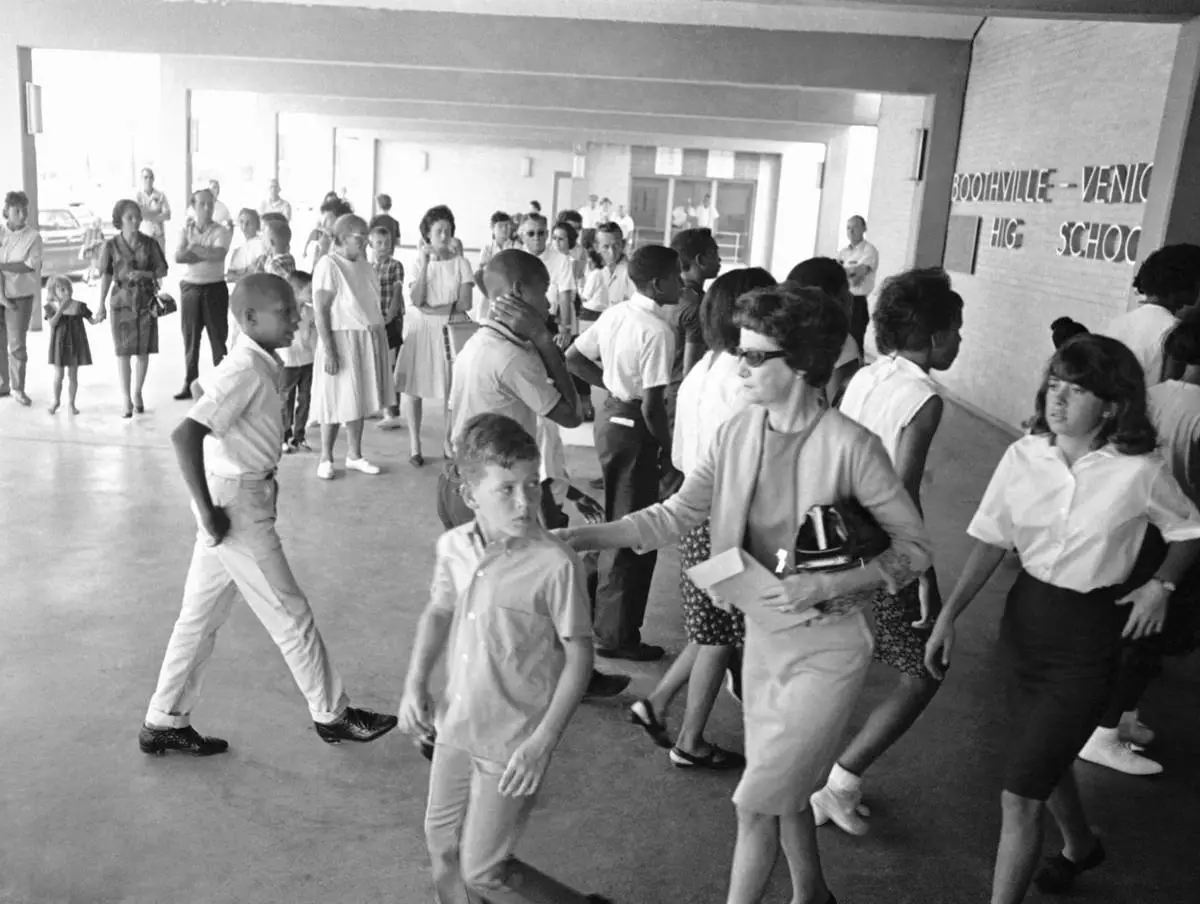

FILE - A white mother walks with her son past a group of African American students arriving for classes at formerly all-white Boothville Venice High School on Monday, Sept. 12, 1966 as racial barriers fell in Plaquemines Parish. (AP Photo/Jack Thornell, file)

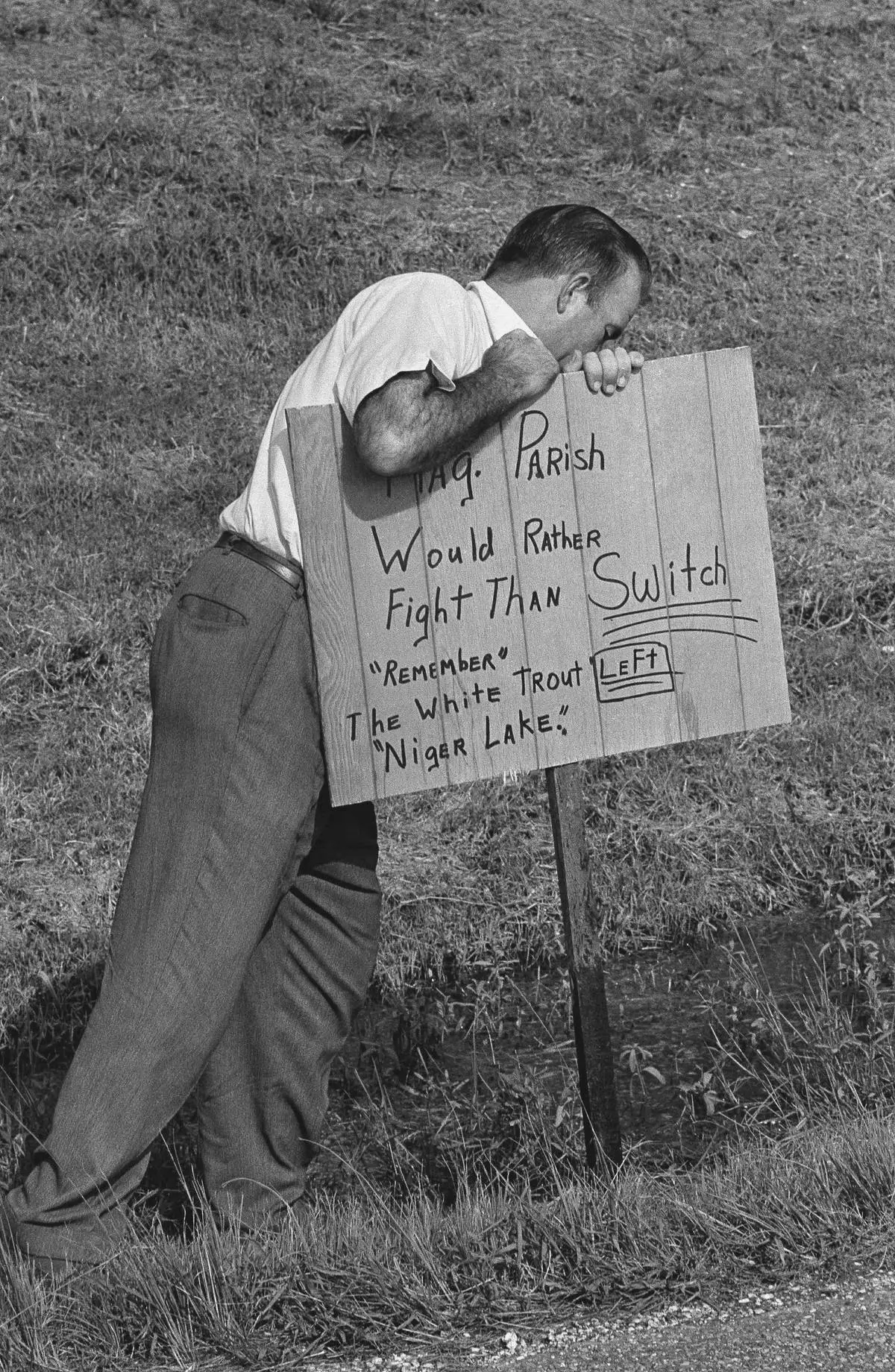

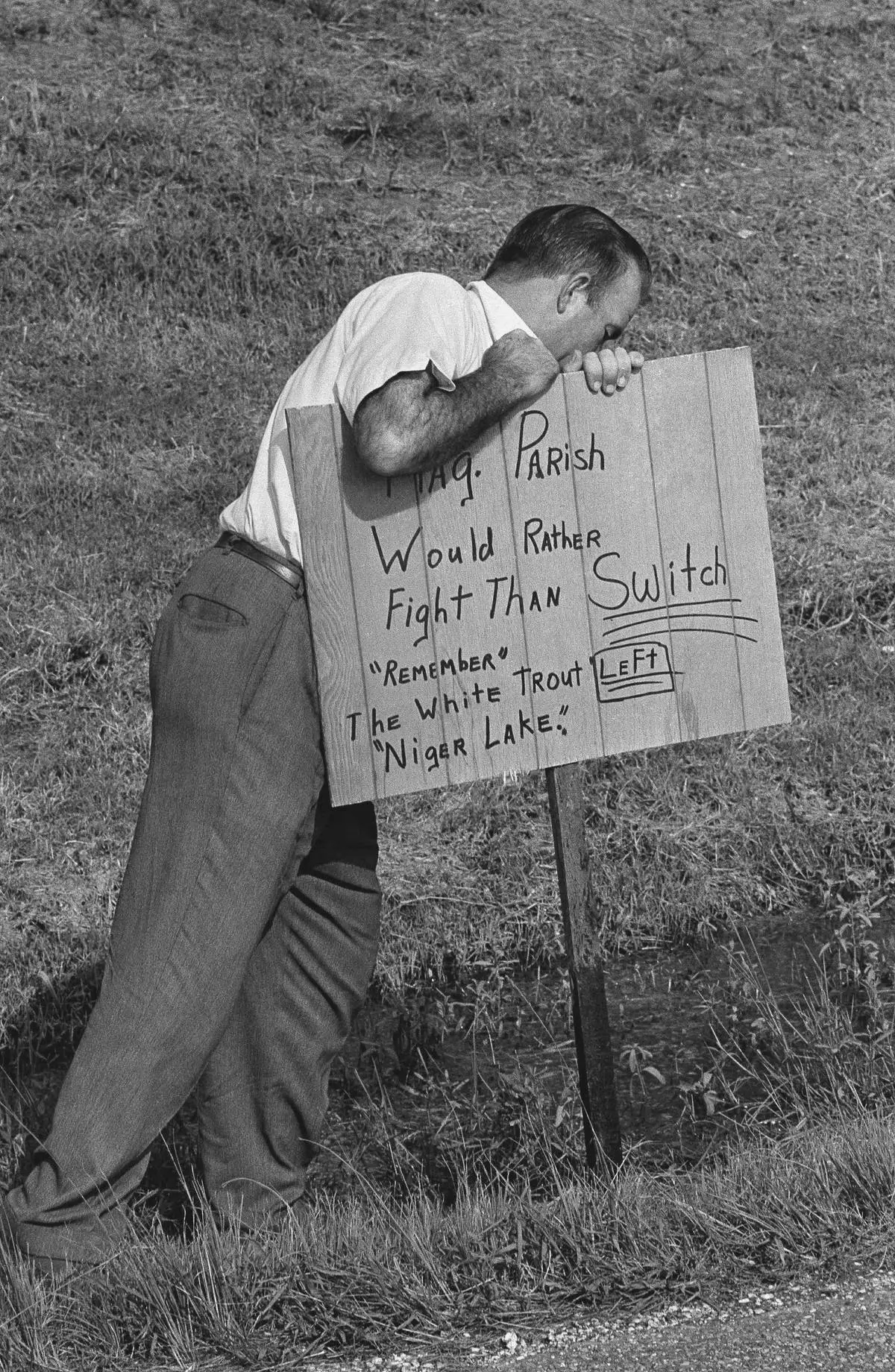

FILE - A man plants a sign reading outside Woodlawn High School in Pointe a la Hache, Louisiana on Sept. 1, 1966 where five African Americans applied for registration for the first time in parish history. (AP Photo/Jack Thornell, file)

FILE - A group of African American students, left, enter the Boothville-Venice School in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana on Sept. 12, 1966 as a group of white mothers wait at the entrance of the school. (AP Photo/Jack Thornell, file)