COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. (AP) — It was a decision that robbed hundreds of athletes of their once-in-a-lifetime chance at Olympic glory, and for more than four decades, it weighed heavily on the man who made it — Jimmy Carter.

Carter’s passing Sunday has unearthed memories from his 1977-1981 presidency. Somewhere between his greatest foreign-policy success (the Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt) and his greatest failure (the Iran hostage crisis) sits the U.S. boycott of the 1980 Olympics in Moscow.

Click to Gallery

FILE - Flag and sign bearers march around Moscow's Lenin Stadium during closing ceremonies of the XXII Summer Olympic Games in Moscow, on Aug. 3, 1980. (AP Photo/File)

FILE - Passersby examine the new Olympic billboard reading, "Sport Serves Peace," erected after the United States announced it was boycotting the games in Moscow on April 23, 1980. (AP Photo/Yurchenko, File)

FILE - Anita DeFrantz, spokeswoman for the U.S. Olympic Committee's Athletes Advisory Council, flanked by Larry Hough, left, and Fred Newhouse right, answers questions from reporters outside the White House in Washington on April 4, 1980, after White House officials rejected a proposal that would have allowed American athletes to compete at the summer Olympic Games in Moscow. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - F. Don Miller, executive director of the U.S. Olympic Committee, reads a resolution adopted by the U.S. Olympic Committee's House of Delegates to boycott the 1980 Summer Games in Moscow, in Colorado Springs, Colo., April 12, 1980. At left is Robert Kane, president of the U.S. Olympic Committee. (AP Photo/Ed Andrieski, File)

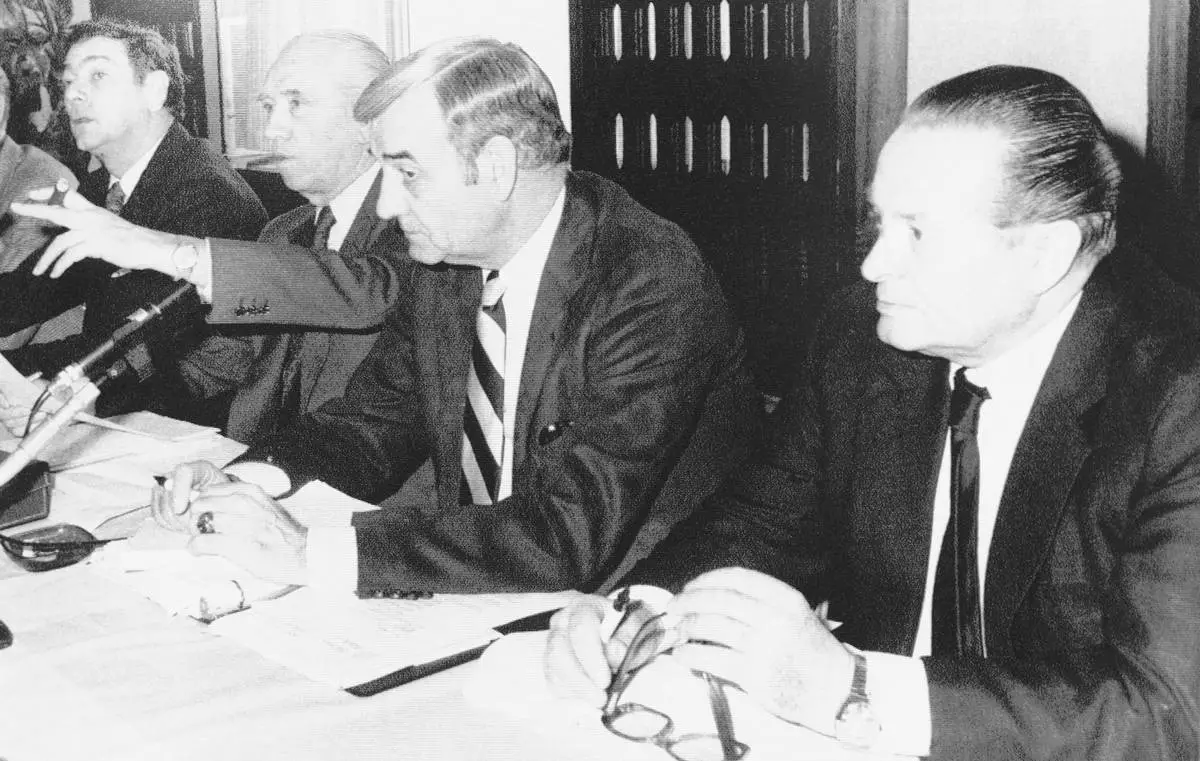

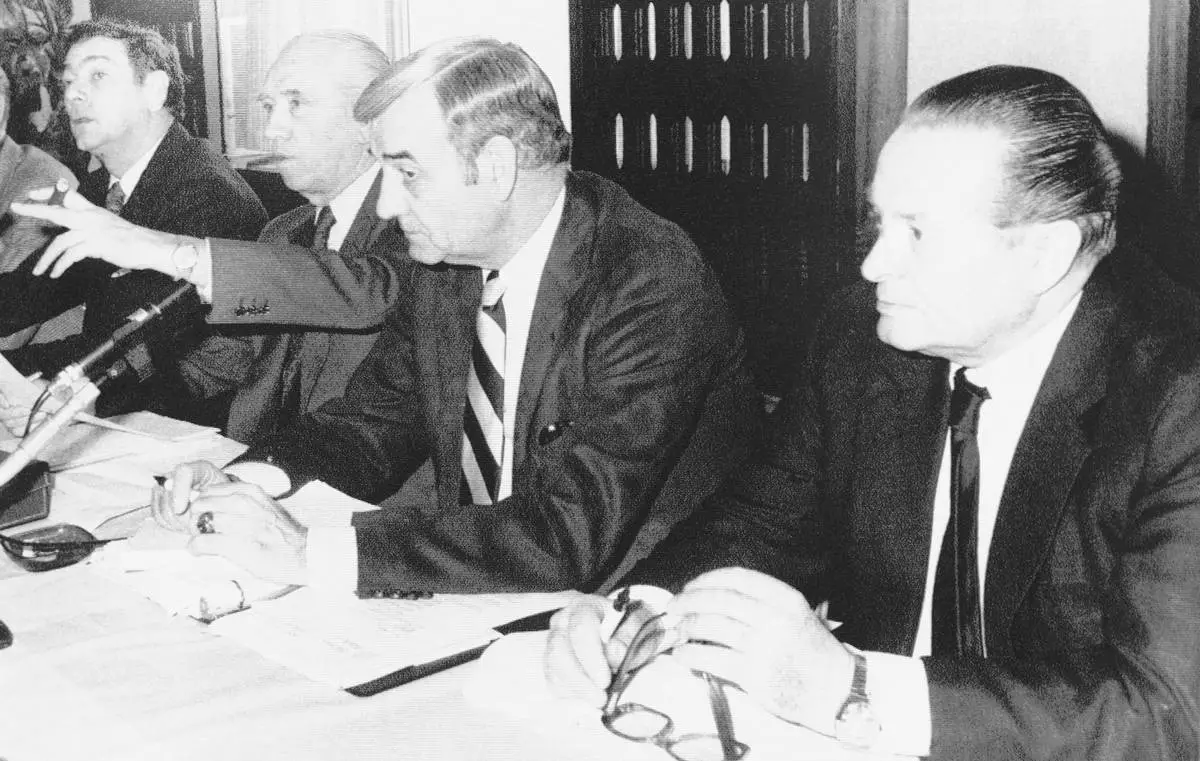

FILE - From left, Belgian representative to the International Olympic Committee (IOC), Prince Alexandre de Merode, President of the Belgian Olympic Committee Raoul Mollet, General Secretary of the U.S. Olympic Committee Col. F. Don Miller, and President of the West German Olympic Committee Willi Daume, are seen during a meeting of officials from 18 Western European Olympic committees to discuss a possible boycott of the MOscow Olympic games on March 22, 1980, in Brussels. (AP Photo/Pierre Thielemans, File)

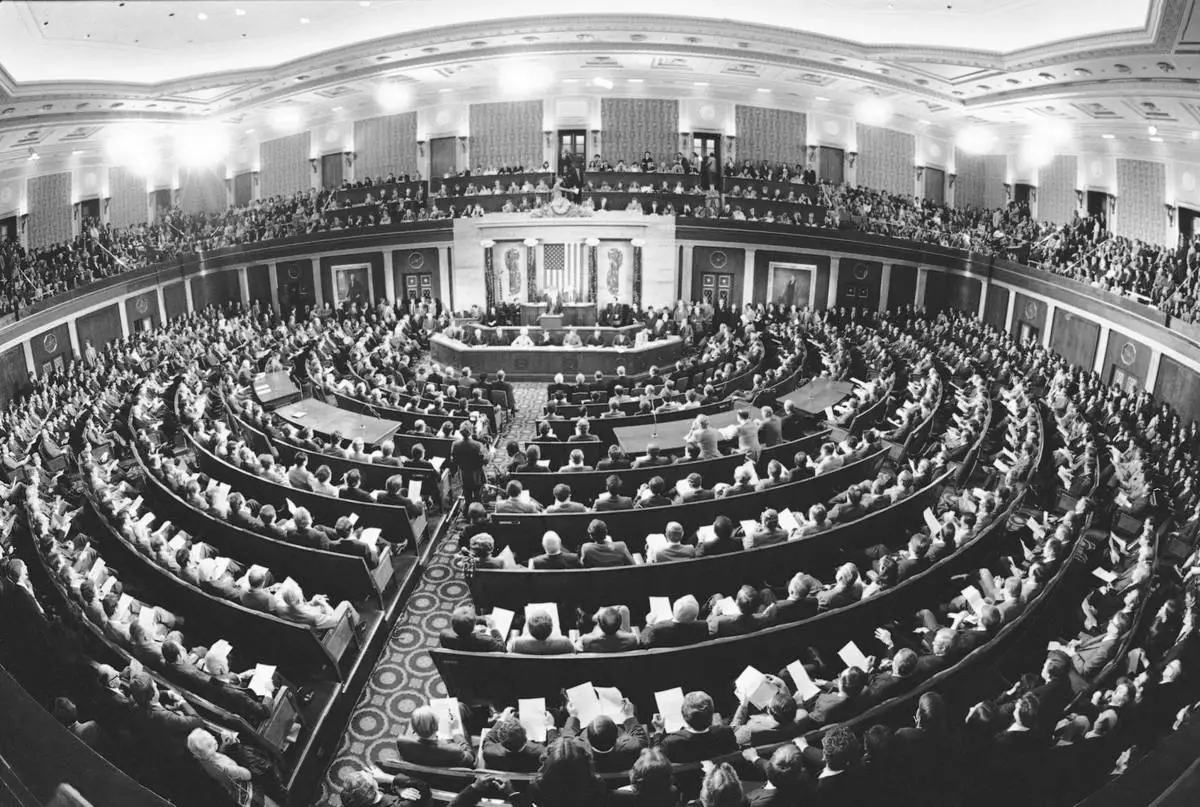

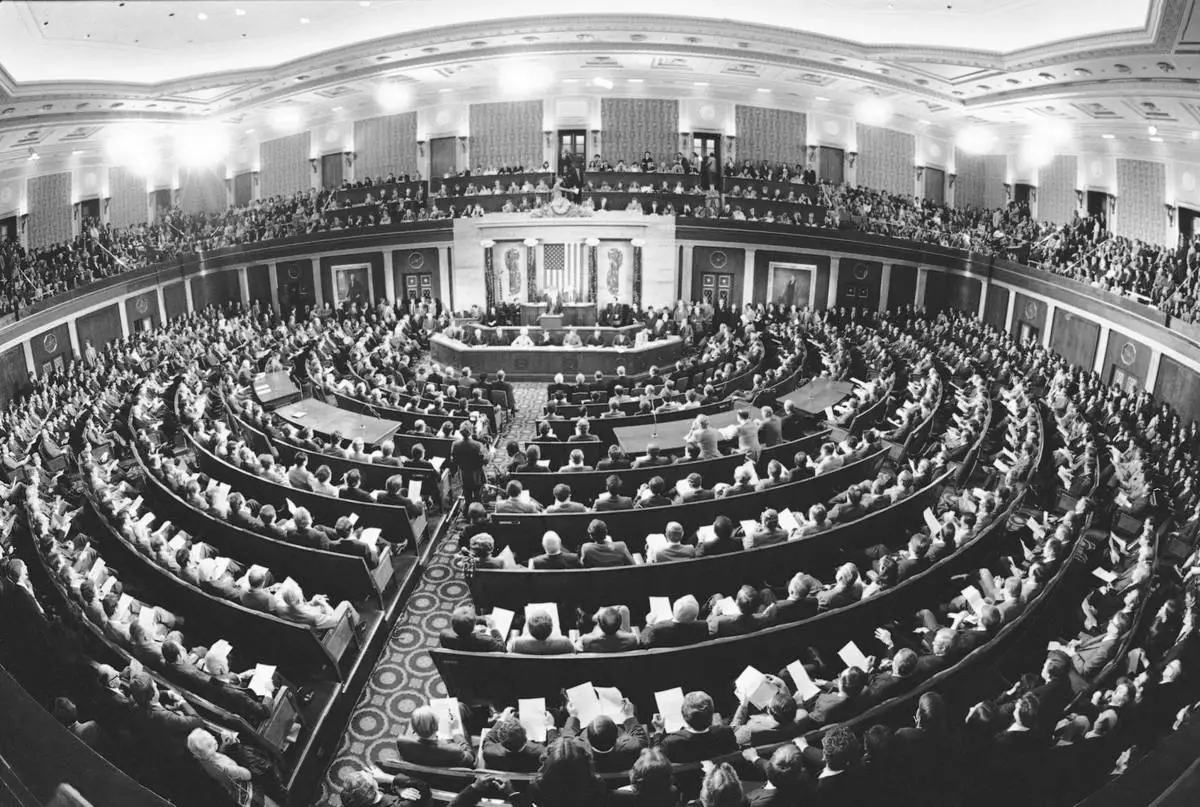

FILE - A wide-angle lens captures the assembled members of Congress in the House Chamber for Carter's State of The Union address in Washington on Jan. 23, 1980. (AP Photo, File)

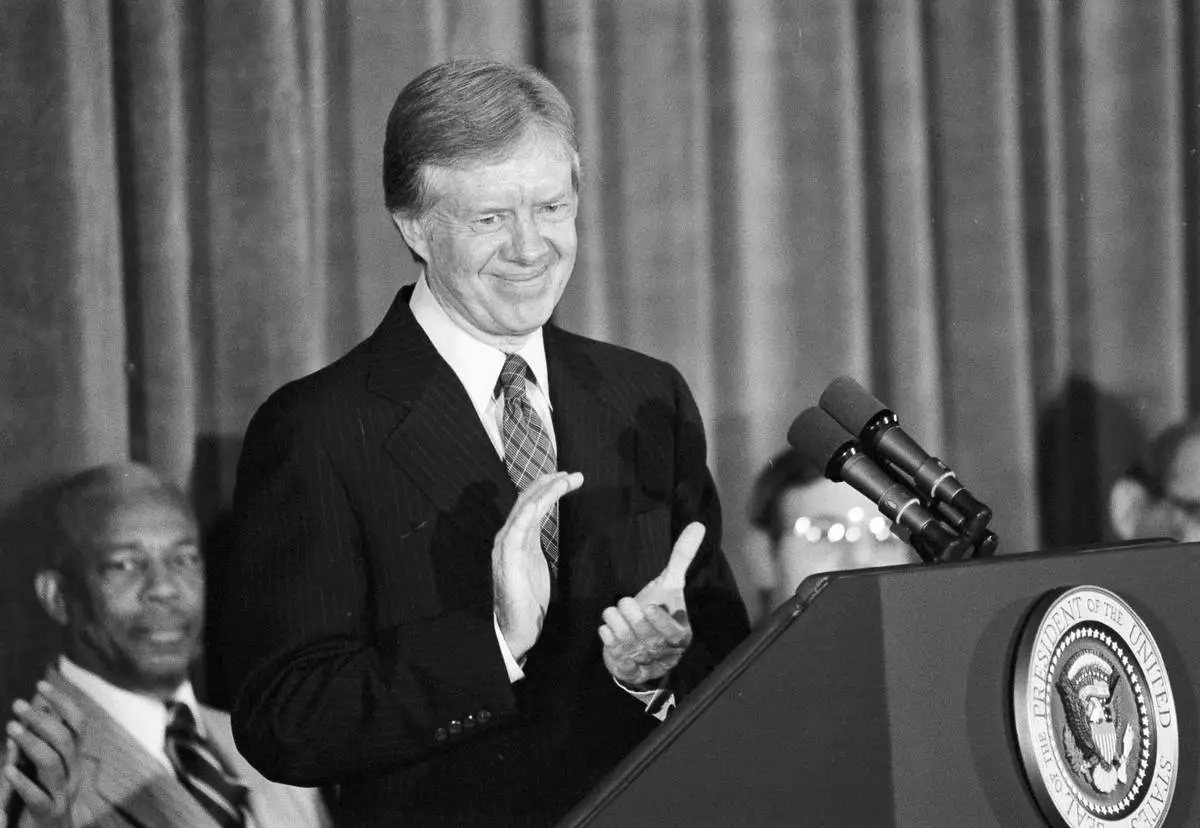

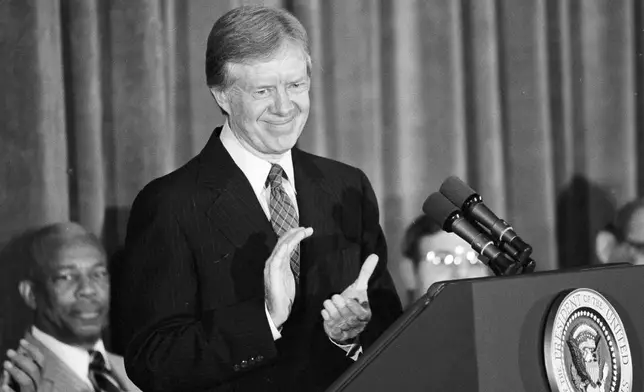

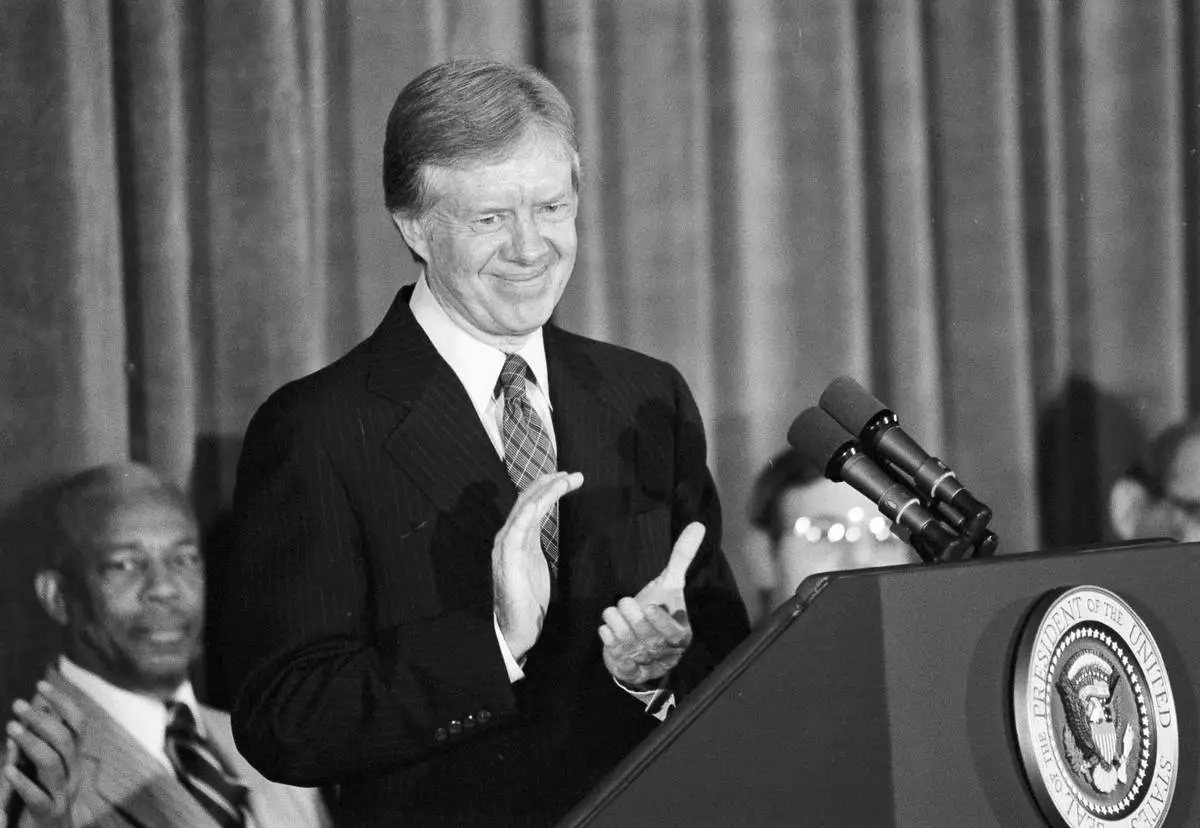

FILE - President Jimmy Carter pauses during a speech to applaud the U.S. Olympic Committee's stand on the Moscow Olympics, Feb. 1, 1980, in Washington. (AP Photo/Mark Wilson, File)

It was Carter who called for that boycott — a Cold War power play intended to express America’s disdain for the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. In his 1980 State of the Union Address, Carter said the invasion “could pose the most serious threat to world peace since the second World War.”

The boycott garnered more than two-thirds support from the 2,400 members of the unwieldy U.S. Olympic Committee house of delegates, the governing body that made the official move to keep the athletes out of Moscow. In short time, that move came to be seen as the textbook example of the risks, confusion and low success rate of injecting politics into sports.

“We were not allowed to go for a not-so-clear reason,” said Edwin Moses, the hurdling great who won 122 straight races between 1977 and 1987, which included the Olympic gold-medal contests in 1976 and 1984.

For decades, members of the 1980 U.S. Olympic team — recognized as Olympians at home but not by the International Olympic Committee abroad — told stories about opportunities missed and dreams unfulfilled because of the trip to Moscow they never took. Of the 474 athletes who had qualified for the team in 1980, 227 would not get another chance to compete in the Olympic Games.

Many athletes told stories of meeting Carter at a White House visit in the summer of 1980 that served as a tepid substitute. In Washington, the athletes received the highest honor civilians can receive from Congress: the Congressional gold medal. But those medals were only gold-plated bronze, not pure gold, and they weren’t recorded in the Congressional record until a push was made nearly three decades later.

Swimmer Jesse Vassallo, a reigning world champion in multiple events at the time, told Swimming World Magazine about meeting Carter in the reception line.

Carter “reached out to shake my hand and he said ‘How would you have done in Moscow?’” Vassallo recalled. “And I said, ‘I would have won two golds and a silver.’ And he just gave me this (pained) look. He didn’t ask anybody else that question.” Wrestler Jeff Blatnick, a champion on the 1984 Olympic team, met Carter on an airplane years later. According to an essay written by the late USOC spokesman Mike Moran, Blatnick said: “He looks at me and says, ‘Were you on the 1980 hockey team?’ I say, ‘No sir, I’m a wrestler, on the summer team.’ He says, ‘Oh, that was a bad decision, I’m sorry.’”

In his 2021 biography on the 39th President, Kai Bird writes that the boycott was a byproduct of a hard line Carter decided to take against the Soviets at the urging of his national security advisor, Zbigniew Brzezinski, who had been in a long-running struggle with the less-hawkish Secretary of State, Cyrus Vance, to influence Carter’s thinking. "History would prove Vance correct; Brzezinski’s ‘Carter Doctrine’ never amounted to much more than a cover for wasteful arms exports,” Bird wrote.

And Carter’s boycott did nothing to deter the Soviets. They stayed in Afghanistan for another nine years, while further disrupting the Olympic movement and America’s own turn as an Olympic host four years later. The Soviets and 13 other countries, mostly from the Eastern Bloc, boycotted the Los Angeles Olympics in 1984 in retaliation for what the Americans had done to Moscow four years earlier.

Forty-four years after Carter’s fateful decision, the Olympics remain every bit as politicized and polarized as they were back then. And for the past several years, the world has grappled with Russia’s place in international sports in the wake of another invasion — this time, into neighboring Ukraine.

How that war is resolved will help define Russia's role when the Olympics come back to Los Angeles in 2028.

FILE - Flag and sign bearers march around Moscow's Lenin Stadium during closing ceremonies of the XXII Summer Olympic Games in Moscow, on Aug. 3, 1980. (AP Photo/File)

FILE - Passersby examine the new Olympic billboard reading, "Sport Serves Peace," erected after the United States announced it was boycotting the games in Moscow on April 23, 1980. (AP Photo/Yurchenko, File)

FILE - Anita DeFrantz, spokeswoman for the U.S. Olympic Committee's Athletes Advisory Council, flanked by Larry Hough, left, and Fred Newhouse right, answers questions from reporters outside the White House in Washington on April 4, 1980, after White House officials rejected a proposal that would have allowed American athletes to compete at the summer Olympic Games in Moscow. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - F. Don Miller, executive director of the U.S. Olympic Committee, reads a resolution adopted by the U.S. Olympic Committee's House of Delegates to boycott the 1980 Summer Games in Moscow, in Colorado Springs, Colo., April 12, 1980. At left is Robert Kane, president of the U.S. Olympic Committee. (AP Photo/Ed Andrieski, File)

FILE - From left, Belgian representative to the International Olympic Committee (IOC), Prince Alexandre de Merode, President of the Belgian Olympic Committee Raoul Mollet, General Secretary of the U.S. Olympic Committee Col. F. Don Miller, and President of the West German Olympic Committee Willi Daume, are seen during a meeting of officials from 18 Western European Olympic committees to discuss a possible boycott of the MOscow Olympic games on March 22, 1980, in Brussels. (AP Photo/Pierre Thielemans, File)

FILE - A wide-angle lens captures the assembled members of Congress in the House Chamber for Carter's State of The Union address in Washington on Jan. 23, 1980. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - President Jimmy Carter pauses during a speech to applaud the U.S. Olympic Committee's stand on the Moscow Olympics, Feb. 1, 1980, in Washington. (AP Photo/Mark Wilson, File)

VINEYARD HAVEN, Mass. (AP) — Lewis Pugh has followed an unspoken rule during his career as one of the world’s most daring endurance swimmers: Don’t talk about sharks. But he plans to break that this week on a swim around Martha’s Vineyard, where “ Jaws” was filmed 50 years ago.

The British-South African was the first person to complete a long-distance swim in every ocean of the world — and has taken on extreme conditions everywhere from Mount Everest to the Arctic.

“On this swim, it’s very different: We’re just talking about sharks all the time,” joked Pugh, who will, as usual, wear no wetsuit.

For his swim around Martha’s Vineyard in 47-degree (8-degree Celsius) water he will wear just trunks, a cap and goggles.

Pugh, 55, is undertaking the challenge because he wants to change public perception around the now at-risk animals — which he said were maligned by the blockbuster film as “villains, as cold-blooded killers.” He will urge for more protection for sharks.

On Thursday, beginning at the Edgartown Harbor Lighthouse, he will swim for three or four hours in the brutally cold surf, mark his progress and spend the rest of his waking hours on the Vineyard educating the public about sharks. Then, he'll get in the water and do it again — and again, for an estimated 12 days, or however long it takes him to complete the 62-mile (100-kilometer) swim.

He begins the journey just after the New England Aquarium confirmed the first white shark sighting of the season, earlier this week off the coast of Nantucket.

“It’s going to test me not only physically, but also mentally,” he said, while scoping out wind conditions by the starting line. “I mean every single day I’m going to be speaking about sharks, sharks, sharks, sharks. Then, ultimately, I’ve got to get in the water afterwards and do the swim. I suppose you can imagine what I’ll be thinking about.”

Pugh said the swim will be among the most difficult he’s undertaken, which says a lot for someone who has swum near glaciers and volcanoes, and among hippos, crocodiles and polar bears. No one has ever swum around the island of Martha's Vineyard before.

But Pugh, who often swims to raise awareness for environmental causes — and was this year named the United Nations Patron of the Oceans — said no swim is without risk and that drastic measures are needed to get his message across: Around 274,000 sharks are killed globally each day — a rate of 100 million every year, according to the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

“It was a film about sharks attacking humans and for 50 years, we have been attacking sharks,” he said of “Jaws.” “It’s completely unsustainable. It’s madness. We need to respect them.”

He emphasizes that the swim is not something nonprofessionals should attempt. He’s accompanied by safety personnel in a boat and kayak and uses a “Shark Shield” device that deters sharks using an electric field without harming them.

Pugh remembers feeling fear as a 16-year-old watching “Jaws” for the first time. Over decades of study and research, awe and respect have replaced his fear, as he realized the role they play in maintaining Earth’s increasingly fragile ecosystems.

“I’m more terrified of a world without sharks, or without predators,” he said.

“Jaws” is credited for creating Hollywood’s blockbuster culture when it was released in summer 1975, becoming the highest grossing film up until that time and earning three Academy Awards. It would impact how many viewed the ocean for decades to come.

Both director Steven Spielberg and author Peter Benchley have expressed regret over the impact of the film on viewers’ perception of sharks. Both have since contributed to conservation efforts for animals, which have seen populations depleted due to factors like overfishing and climate change.

Discovery Channel and the National Geographic Channel each year release programming about sharks to educate the public about the predator.

Greg Skomal, marine fisheries biologist at Martha’s Vineyard Fisheries within the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries, said many people tell him they still won't swim in the ocean because of the sheer terror caused by the film.

“I tend to hear the expression that, ‘I haven’t gone in the water since ‘Jaws’ came out,’” he said.

But Skomal, who published a book challenging the film's inaccuracies, said “Jaws” also inspired many people — including him — to study marine biology, leading to increased research, acceptance and respect for the creatures.

If “Jaws” were made today, he doesn't think it'd have the same effect. But in the 1970s, “it was just perfect in terms of generating this level of fear to a public that was largely uneducated about sharks, because we were uneducated. Scientists didn’t know a lot about sharks.”

Skomal said the biggest threat contributing to the decline of the shark population now is commercial fishing, which exploded in the late 1970s and is today driven by high demand for fins and meat used in food dishes, as well as the use of skin to make leather and oil and cartilage for cosmetics.

“I think we’ve really moved away from this feeling, or the old adage that, ‘The only good shark is a dead shark,’” he said. “We’re definitely morphing from fear to fascination, or perhaps a combination of both.”

A woman views the sunset at Menemsha Beach, Wednesday, May 14, 2025, in Chilmark, Mass. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty)

A man navigates the wake behind the Martha's Vineyard Ferry, Monday, May 12, 2025, in Vineyard Haven, Mass. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

A visitor arrives at a shop selling Jaws-related souvenirs, Wednesday, May 14, 2025, in Edgartown, Mass. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty)

A shopper walks past items featuring the Jaws movie at Neptune's Sea Chest gift shop, Monday, May 12, 2025, in Vineyard Haven, Mass., on Martha's Vineyard Island. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Endurance swimmer Lewis Pugh gestures to where he will begin his swim around Martha's Vineyard island, which is expected to take 12 days, near the Edgartown Lighthouse, Monday, May 12, 2025, in Edgartown, Mass. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

A family walks to the span of the American Legion Memorial Bridge, also known as the "Jaws Bridge", while spending the day fishing, Monday, May 12, 2025, in Edgartown, Mass., on Martha's Vineyard Island. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)