Five years ago, a cluster of people in Wuhan, China, fell sick with a virus never before seen in the world.

The germ didn't have a name, nor did the illness it would cause. It wound up setting off a pandemic that exposed deep inequities in the global health system and reshaped public opinion about how to control deadly emerging viruses.

The virus is still with us, though humanity has built up immunity through vaccinations and infections. It's less deadly than it was in the pandemic's early days and it no longer tops the list of leading causes of death. But the virus is evolving, meaning scientists must track it closely.

We don’t know. Scientists think the most likely scenario is that it circulated in bats, like many coronaviruses. They think it then infected another species, probably racoon dogs, civet cats or bamboo rats, which in turn infected humans handling or butchering those animals at a market in Wuhan, where the first human cases appeared in late November 2019.

That's a known pathway for disease transmission and likely triggered the first epidemic of a similar virus, known as SARS. But this theory has not been proven for the virus that causes COVID-19. Wuhan is home to several research labs involved in collecting and studying coronaviruses, fueling debate over whether the virus instead may have leaked from one.

It's a difficult scientific puzzle to crack in the best of circumstances. The effort has been made even more challenging by political sniping around the virus' origins and by what international researchers say are moves by China to withhold evidence that could help.

The true origin of the pandemic may not be known for many years — if ever.

Probably more than 20 million. The World Health Organization has said member countries reported more than 7 million deaths from COVID-19 but the true death toll is estimated to be at least three times higher.

In the U.S., an average of about 900 people a week have died of COVID-19 over the past year, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The coronavirus continues to affect older adults the most. Last winter in the U.S., people age 75 and older accounted for about half the nation’s COVID-19 hospitalizations and in-hospital deaths, according to the CDC.

“We cannot talk about COVID in the past, since it’s still with us,” WHO director Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said.

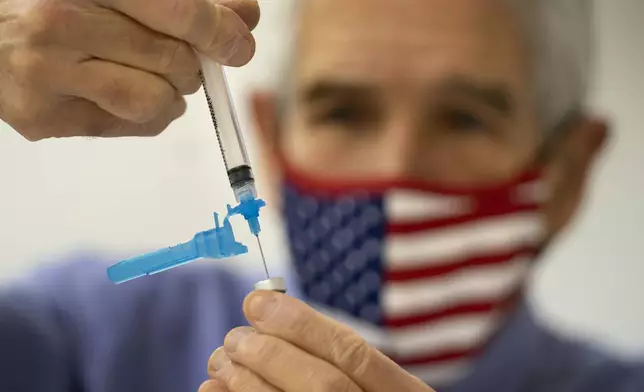

Scientists and vaccine-makers broke speed records developing COVID-19 vaccines that have saved tens of millions of lives worldwide – and were the critical step to getting life back to normal.

Less than a year after China identified the virus, health authorities in the U.S. and Britain cleared vaccines made by Pfizer and Moderna. Years of earlier research — including Nobel-winning discoveries that were key to making the new technology work — gave a head start for so-called mRNA vaccines.

Today, there’s also a more traditional vaccine made by Novavax, and some countries have tried additional options. Rollout to poorer countries was slow but the WHO estimates more than 13 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines have been administered globally since 2021.

The vaccines aren't perfect. They do a good job of preventing severe disease, hospitalization and death, and have proven very safe, with only rare serious side effects. But protection against milder infection begins to wane after a few months.

Like flu vaccines, COVID-19 shots must be updated regularly to match the ever-evolving virus — contributing to public frustration at the need for repeated vaccinations. Efforts to develop next-generation vaccines are underway, such as nasal vaccines that researchers hope might do a better job of blocking infection.

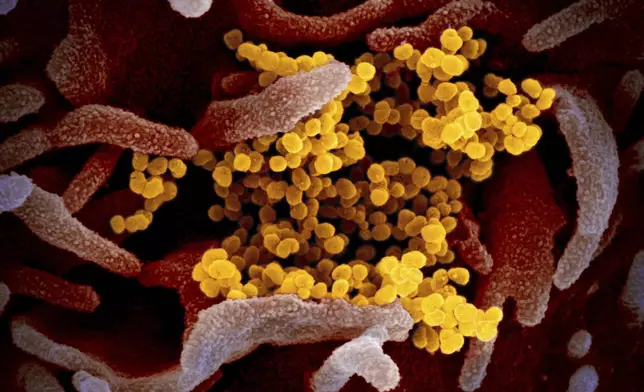

Genetic changes called mutations happen as viruses make copies of themselves. And this virus has proven to be no different.

Scientists named these variants after Greek letters: alpha, beta, gamma, delta and omicron. Delta, which became dominant in the U.S. in June 2021, raised a lot of concerns because it was twice as likely to lead to hospitalization as the first version of the virus.

Then in late November 2021, a new variant came on the scene: omicron.

“It spread very rapidly," dominating within weeks, said Dr. Wesley Long, a pathologist at Houston Methodist in Texas. “It drove a huge spike in cases compared to anything we had seen previously.”

But on average, the WHO said, it caused less severe disease than delta. Scientists believe that may be partly because immunity had been building due to vaccination and infections.

“Ever since then, we just sort of keep seeing these different subvariants of omicron accumulating more different mutations,” Long said. “Right now, everything seems to locked on this omicron branch of the tree.”

The omicron relative now dominant in the U.S. is called XEC, which accounted for 45% of variants circulating nationally in the two-week period ending Dec. 21, the CDC said. Existing COVID-19 medications and the latest vaccine booster should be effective against it, Long said, since “it’s really sort of a remixing of variants already circulating.”

Millions of people remain in limbo with a sometimes disabling, often invisible, legacy of the pandemic called long COVID.

It can take several weeks to bounce back after a bout of COVID-19, but some people develop more persistent problems. The symptoms that last at least three months, sometimes for years, include fatigue, cognitive trouble known as “brain fog,” pain and cardiovascular problems, among others.

Doctors don’t know why only some people get long COVID. It can happen even after a mild case and at any age, although rates have declined since the pandemic's early years. Studies show vaccination can lower the risk.

It also isn't clear what causes long COVID, which complicates the search for treatments. One important clue: Increasingly researchers are discovering that remnants of the coronavirus can persist in some patients’ bodies long after their initial infection, although that can’t explain all cases.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

FILE - Nancy Rose, who contracted COVID-19 in 2021 and exhibits long-haul symptoms including brain fog and memory difficulties, pauses while organizing her desk space, Jan. 25, 2022, in Port Jefferson, N.Y. (AP Photo/John Minchillo, File)

FILE - Denmark's Jonas Vingegaard, left, and teammate Matteo Jorgenson, of the U.S., wear face masks to protect themselves from the Corona virus prior to the start of the fourteenth stage of the Tour de France cycling race over 151.9 kilometers (94.4 miles) with start in Pau and finish in Saint-Lary-Soulan Pla d'Adet, France, July 13, 2024. Several riders had to abandon the race after contracting COVID-19. (AP Photo/Daniel Cole, File)

FILE - Dr. Sydney Sewall fills a syringe with the COVID-19 vaccine at the Augusta Armory, Dec. 21, 2021, in Augusta, Maine. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty, File)

FILE - Cemetery workers in protective gear bury a person alongside rows of freshly dug graves at the Vila Formosa cemetery in Sao Paulo, Brazil, April 1, 2020. (AP Photo/Andre Penner, File)

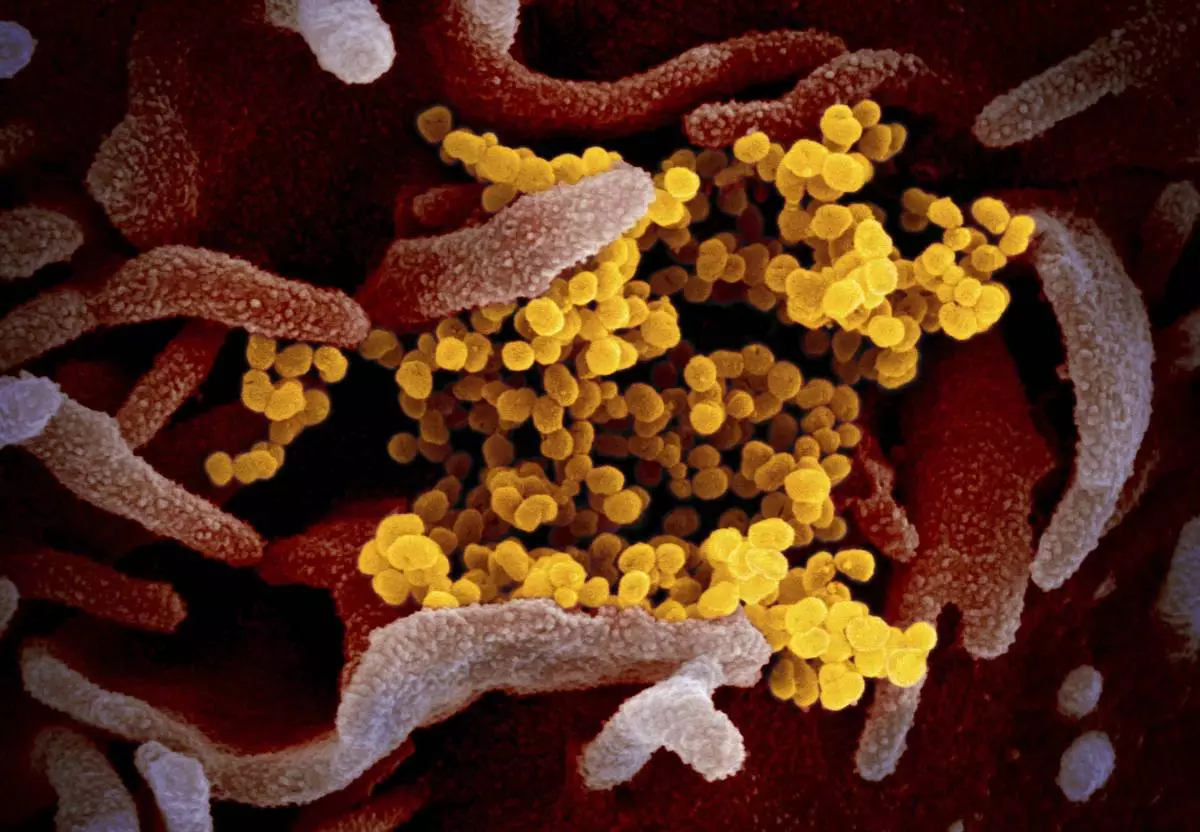

FILE - This undated electron microscope image made available by the U.S. National Institutes of Health in February 2020 shows the Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, yellow, emerging from the surface of cells, pink, cultured in the lab. Also known as 2019-nCoV, the virus causes COVID-19. The sample was isolated from a patient in the U.S. (NIAID-RML via AP, File)

FILE - People attend an exhibition on the city's fight against the coronavirus in Wuhan in central China's Hubei province, Jan. 23, 2021. (AP Photo/Ng Han Guan, File)

FILE - A medical worker takes a swab sample from a worker of the China Star Optoelectronics Technology (CSOT) company during a round of COVID-19 tests in Wuhan in central China's Hubei province, Aug. 5, 2021. (Chinatopix via AP, File)