WASHINGTON (AP) — The congressional joint session to count electoral votes on Monday is expected to be much less eventful than the certification four years ago that was interrupted by a violent mob of supporters of then-President Donald Trump who tried to stop the count and overturn the results of an election he lost to Democrat Joe Biden.

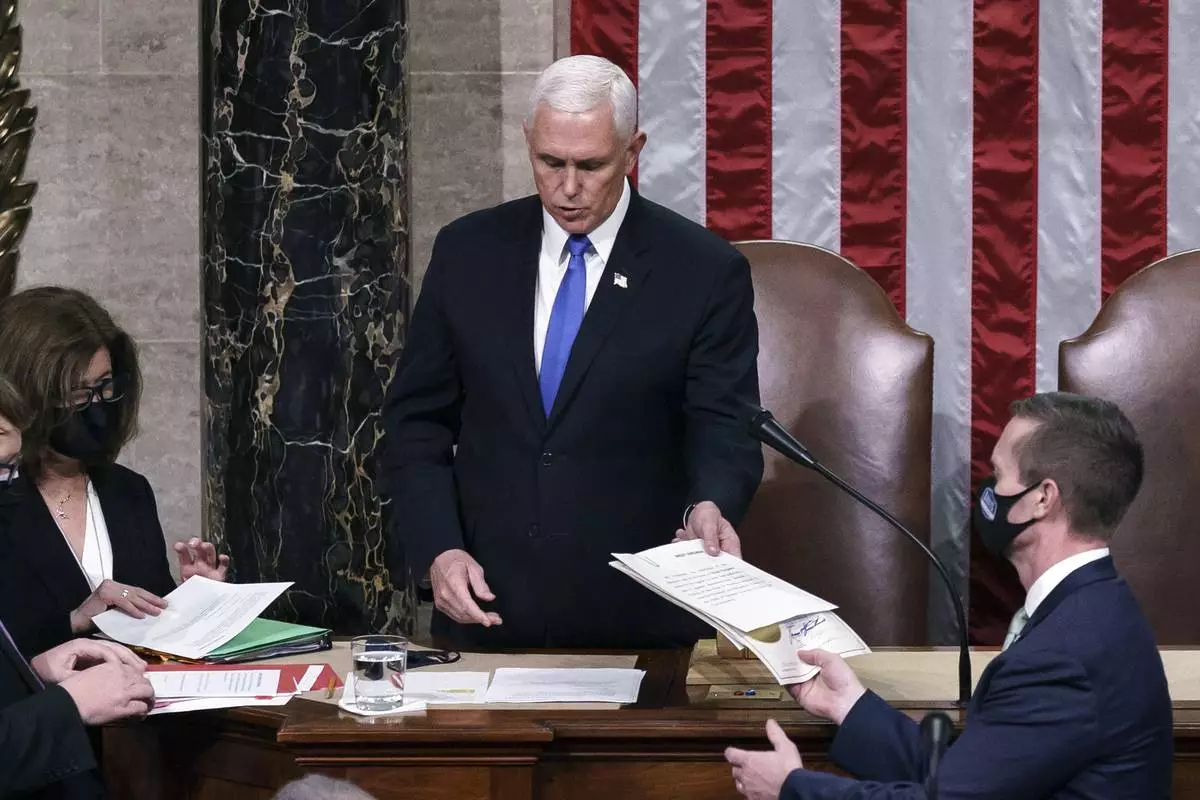

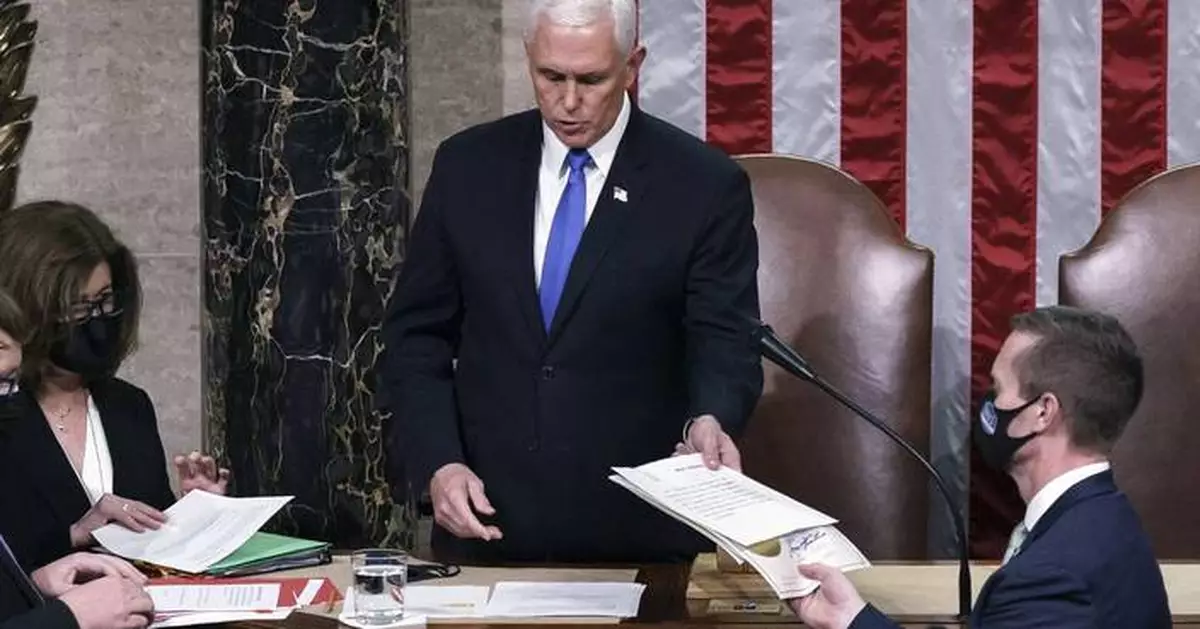

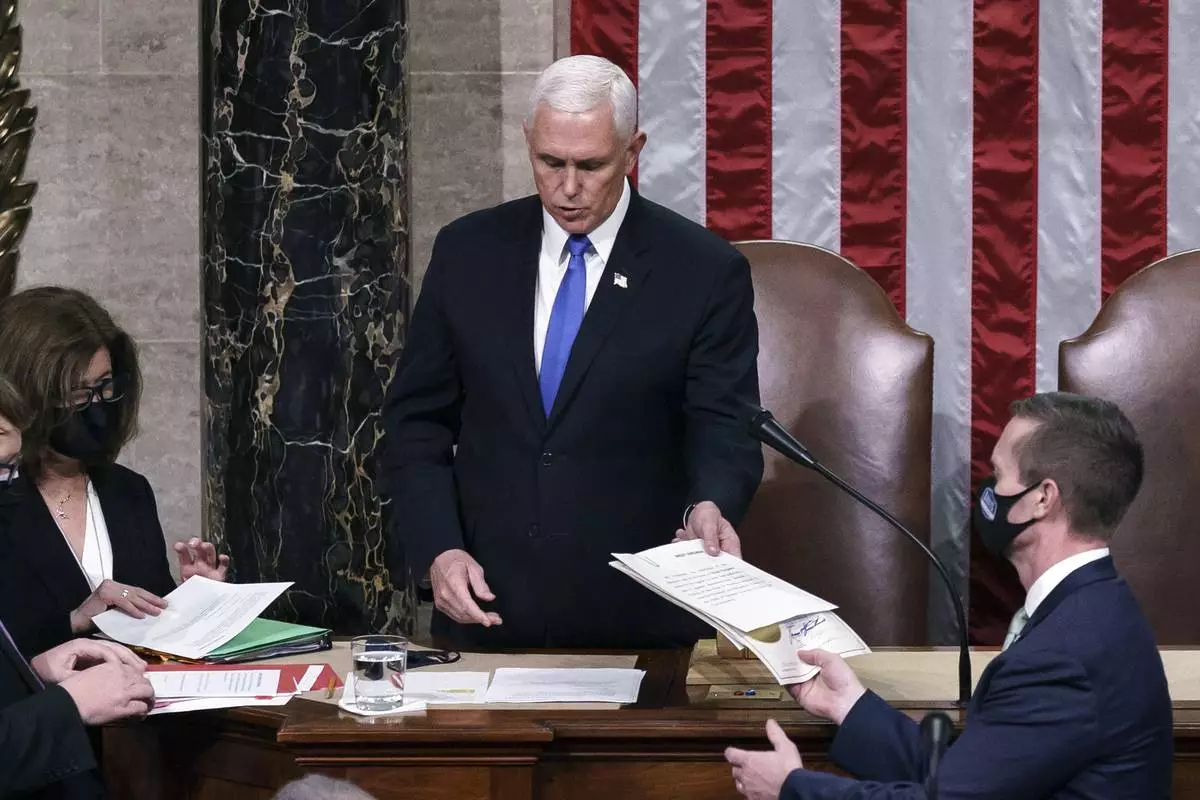

This time, Trump is returning to office after winning the 2024 election that began with Biden as his party's nominee and ended with Vice President Kamala Harris atop the ticket. She will preside over the certification of her own loss, fulfilling the constitutional role in the same way that Trump's vice president, Mike Pence, did after the violence subsided on Jan. 6, 2021.

Usually a routine affair, the congressional joint session on Jan. 6 every four years is the final step in reaffirming a presidential election after the Electoral College officially elects the winner in December. The meeting is required by the Constitution and includes several distinct steps.

A look at the joint session:

Under federal law, Congress must meet Jan. 6 to open sealed certificates from each state that contain a record of their electoral votes. The votes are brought into the chamber in special mahogany boxes that are used for the occasion.

Bipartisan representatives of both chambers read the results out loud and do an official count. The vice president, as president of the Senate, presides over the session and declares the winner.

The Constitution requires Congress to meet and count the electoral votes. If there is a tie, then the House decides the presidency, with each congressional delegation having one vote. That hasn’t happened since the 1800s, and won't happen this time because Trump’s electoral win over Harris was decisive, 312-226.

Congress tightened the rules for the certification after the violence of 2021 and Trump’s attempts to usurp the process.

In particular, the revised Electoral Count Act passed in 2022 more explicitly defines the role of the vice president after Trump aggressivelypushed Pence to try and object to the Republican's defeat — an action that would have gone far beyond Pence's ceremonial role. Pence rebuffed Trump and ultimately gaveled down his own defeat. Harris will do the same.

The updated law clarifies that the vice president does not have the power to determine the results on Jan. 6.

Harris and Pence were not the first vice presidents to be put in the uncomfortable position of presiding over their own defeats. In 2001, Vice President Al Gore presided over the counting of the 2000 presidential election that he narrowly lost to Republican George W. Bush. Gore had to gavel several Democrats’ objections out of order.

In 2017, Biden as vice president presided over the count that declared Trump the winner. Biden also shot down objections from House Democrats that did not have any Senate support.

The presiding officer opens and presents the certificates of the electoral votes in alphabetical order of the states.

The appointed “tellers” from the House and Senate, members of both parties, then read each certificate out loud and record and count the votes. At the end, the presiding officer announces who has won the majority votes for both president and vice president.

After a teller reads the certificate from any state, a lawmaker can stand up and object to that state’s vote on any grounds. But the presiding officer will not hear the objection unless it is in writing and signed by one-fifth of each chamber.

That threshold is significantly higher than what came before. Previously, a successful objection only required support from one member of the Senate and one member of the House. Lawmakers raised the threshold in the 2022 law to make objections more difficult.

If any objection reaches the threshold — something not expected this time — the joint session suspends and the House and Senate go into separate sessions to consider it. For the objection to be sustained, both chambers must uphold it by a simple majority vote. If they do not agree, the original electoral votes are counted with no changes.

In 2021, both the House and Senate rejected challenges to the electoral votes in Arizona and Pennsylvania.

Before 2021, the last time that such an objection was considered had been 2005, when Rep. Stephanie Tubbs Jones of Ohio and Sen. Barbara Boxer of California, both Democrats, objected to Ohio’s electoral votes, claiming there were voting irregularities. Both the House and Senate debated the objection and easily rejected it. It was only the second time such a vote had occurred.

After Congress certifies the vote, the president is inaugurated on the west front of the Capitol on Jan. 20.

The joint session is the last official chance for objections, beyond any challenges in court. Harris has conceded and never disputed Trump’s win.

FILE - Rep. Cynthia McKinney, D-Ga., lower left, objects to Florida's electoral vote count results, as Vice President Al Gore, standing, top center, and House Speaker Dennis Hastert, R-Ill., seated, top right, listen on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives, in Washington, Jan. 6, 2001. Other members present, seated at left in middle row are: Sen. Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., Chris Dodd, D-Ct, hand over mouth., Chaka Fattah, D-Pa., standing at podium and Rep. William Thomas, R-Calif. Others not identified. (AP Photo/Kenneth Lambert, File)

FILE - Vice President Mike Pence returns to the House chamber after midnight, Jan. 7, 2021, to finish the work of the Electoral College after a mob loyal to President Donald Trump stormed the Capitol in Washington and disrupted the process. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite, File)

WASHINGTON (AP) — It's the largest prosecution in Justice Department history — with reams of evidence, harrowing videos and hundreds of convictions of the rioters who stormed the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. Now Donald Trump's return to power has thrown into question the future of the more than 1,500 federal cases brought over the last four years.

Jan. 6 trials, guilty pleas and sentencings have continued chugging along in Washington's federal court despite Trump's promise to pardon rioters, whom he has called “political prisoners" and “hostages” he contends were treated too harshly.

Here's a look at where the prosecutions stand on the fourth anniversary of the Capitol riot and what could happen next:

More than 1,500 people across the U.S. have been charged with federal crimes related to the deadly riot. Hundreds of people who did not engage in destruction or violence were charged only with misdemeanor offenses for entering the Capitol illegally. Others were charged with felony offenses, including assault for beating police officers. Leaders of the Oath Keepers and the Proud Boys extremist groups were convicted of seditious conspiracy for what prosecutors described as plots to use violence to stop the peaceful transfer of power from Trump, a Republican, to Joe Biden, a Democrat.

About 250 people have been convicted of crimes by a judge or a jury after a trial. Only two people were acquitted of all charges by judges after bench trials. No jury has fully acquitted a Capitol riot defendant. At least 1,020 others had pleaded guilty as of Jan. 1.

More than 1,000 rioters have already been sentenced, with over 700 receiving at least some time behind bars. The rest were given some combination of probation, community service, home detention or fines.

The longest sentence, 22 years, went to former Proud Boys national chairman Enrique Tarrio, who was convicted of seditious conspiracy along with three lieutenants. A California man with a history of political violence got 20 years in prison for repeatedly attacking police with flagpoles and other makeshift weapons during the riot. And Oath Keepers founder Stewart Rhodes is serving an 18-year prison sentence for seditious conspiracy and other offenses.

More than 100 Jan. 6 defendants are scheduled to stand trial in 2025, while at least 168 riot defendants are set to be sentenced this year.

Authorities have continued making new arrests since Trump's election victory. That includes people accused of assaulting police officers who were defending the Capitol.

Citing Trump's promise of pardons, several defendants have sought to have their cases delayed — with little success.

In denying one such request, U.S. District Judge Royce Lamberth, who was nominated to the bench by President Ronald Reagan, a Republican, wrote: "This Court recently had the occasion to discuss what effect the speculative possibility of a presidential pardon has on the timetable for a pending criminal matter. In short: little to none."

One defendant who convinced a judge to postpone his trial, William Pope, told the court that the “American people gave President Trump a mandate to carry out the agenda he campaigned on, which includes ending the January 6 prosecutions and pardoning those who exercised First Amendment rights at the Capitol.” Pope has now asked the judge to allow him to travel to Washington to attend Trump's inauguration on Jan. 20.

Trump embraced the Jan. 6 rioters on the campaign trial, downplaying the violence that was broadcast on live TV and has been documented extensively through video, testimony and other evidence in the federal cases.

Trump has vowed to begin issuing pardons of Jan. 6 rioters on his first day in office. He has said he will look at individuals on a case-by-case basis, but he has not explained how he will decide who receives such relief.

He has said there may be “some exceptions" — if “somebody was radical, crazy." But he has not ruled out pardons for people convicted of serious crimes, like assaulting police officers. When confronted in a recent NBC News interview about the dozens of people who have pleaded guilty to assaulting law enforcement, Trump responded: “Because they had no choice."

Many judges in Washington's federal court have condemned the depiction of the rioters as “political prisoners," and some have raised alarm about the potential pardons.

"No matter what ultimately becomes of the Capital Riots cases already concluded and still pending, the true story of what happened on January 6, 2021 will never change," Judge Lamberth recently said in a statement when handing down a sentence.

U.S. District Judge Carl Nichols, who was nominated to the bench by Trump, has said it would be “beyond frustrating and disappointing” if Trump hands out mass pardons to rioters.

In another case, U.S. District Judge Amit Mehta alluded to the prospect of a pardon for Rhodes, the Oath Keepers founder convicted of seditious conspiracy.

“The notion that Stewart Rhodes could be absolved of his actions is frightening and ought to be frightening to anyone who cares about democracy in this country,” said Mehta, who was nominated by President Barack Obama, a Democrat.

Follow the AP's coverage of the Jan. 6 insurrection at https://apnews.com/hub/capitol-siege.

FILE - Violent protesters loyal to President Donald Trump, including Kevin Seefried, center, holding a Confederate battle flag, are confronted by U.S. Capitol Police officers outside the Senate Chamber inside the Capitol, Jan. 6, 2021 in Washington. (AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta, File)

FILE - Supporters of President Donald Trump climb the west wall of the the U.S. Capitol in Washington, Jan. 6, 2021. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana, File)

FILE - A flag hangs between broken windows after then-President Donald Trump supporters tried to break through police barriers outside the U.S. Capitol, Jan 6, 2021. (AP Photo/John Minchillo, File)

FILE - Insurrectionists loyal to President Donald Trump try to break through a police barrier, Wednesday, Jan. 6, 2021, at the Capitol in Washington. (AP Photo/Julio Cortez, File)