NAIROBI, Kenya (AP) — Jimmy Carter was the first U.S. president to make a state visit to sub-Saharan Africa. He once called helping with Zimbabwe’s transition from white rule to independence “our greatest single success.” And when he died at 100, his foundation’s work in rural Africa had nearly fulfilled his quest to eliminate a disease that afflicted millions, for the first time since the eradication of smallpox.

The African continent, a booming region with a population rivaling China’s that is set to double by 2050, is where Carter's legacy remains most evident. Until his presidency, U.S. leaders had shown little interest in Africa, even as independence movements swept the region in the 1960s and '70s.

Click to Gallery

FILE - Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter, right, greets Southern Sudanese men waiting to cast their vote at a polling station in Juba, Southern Sudan, Jan 9, 2011, during a weeklong referendum on independence that is expected to split Africa's largest nation in two. (AP Photo/Jerome Delay, File)

FILE - Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter helps in the contruction of a low-income housing project in Durban, South Africa, June 6, 2002. Carter was among 4,500 volunteers, organized by Habitat for Humanity, building 100 homes in the coastal city during the week. (AP Photo/Themba Hadebe, File)

FILE - Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter, left, speaks with Ethiopian President Mengistu Haile Mariam in Addis Ababa, July 11, 1990, during the 26th summit of the Organization of African Unity. (AP Photo/Aris Saris, File)

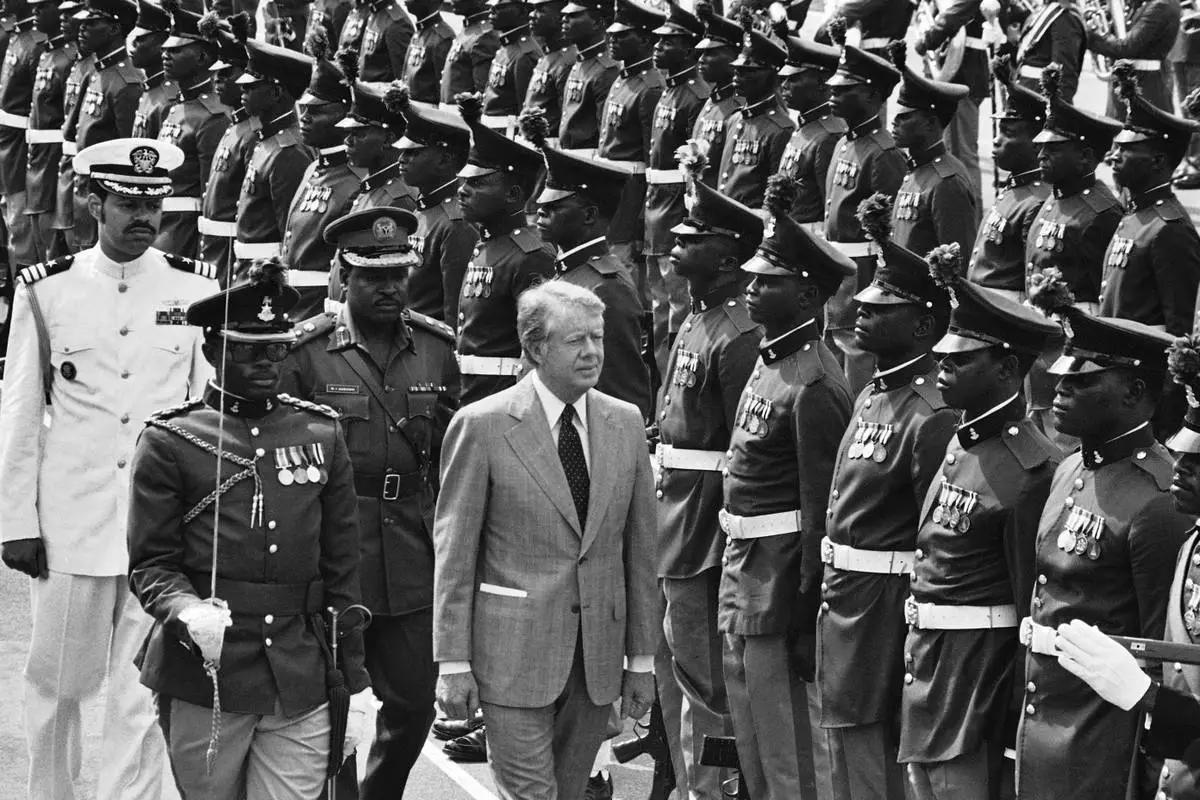

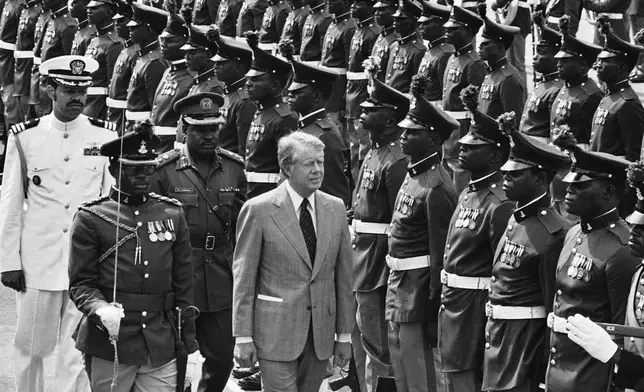

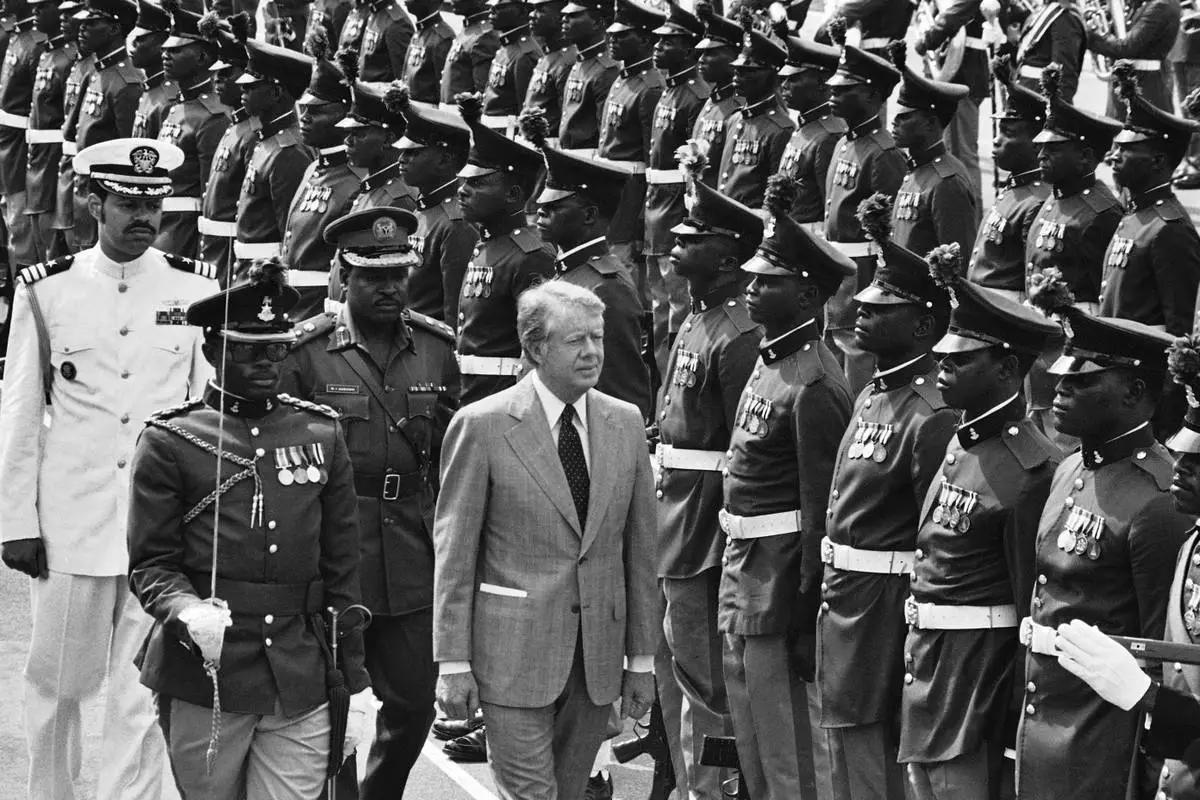

FILE - U.S. President Jimmy Carter reviews honor guards during arrival ceremonies at the Dodan Barracks in Lagos, Nigeria, April 1, 1978. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - President Jimmy Carter meets with Zimbabwean Prime Minister Robert Mugabe in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington, Aug. 27, 1980. (AP Photo/Barry Thumma, File)

FILE - Former South African President Nelson Mandela, left, and former U.S. President Jimmy Carter, right, hold HIV-positive babies at the Zola Clinic in Soweto, March 7, 2002. (AP Photo/Nonthemba Kwela, File)

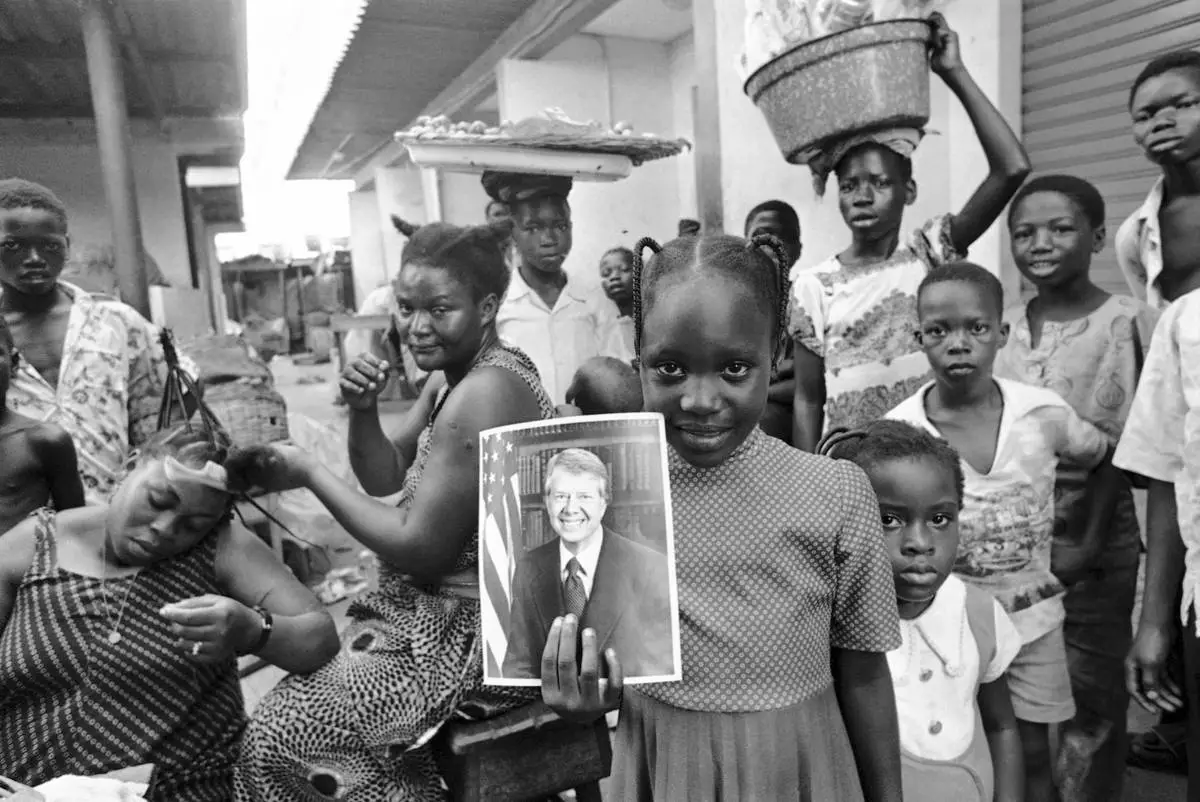

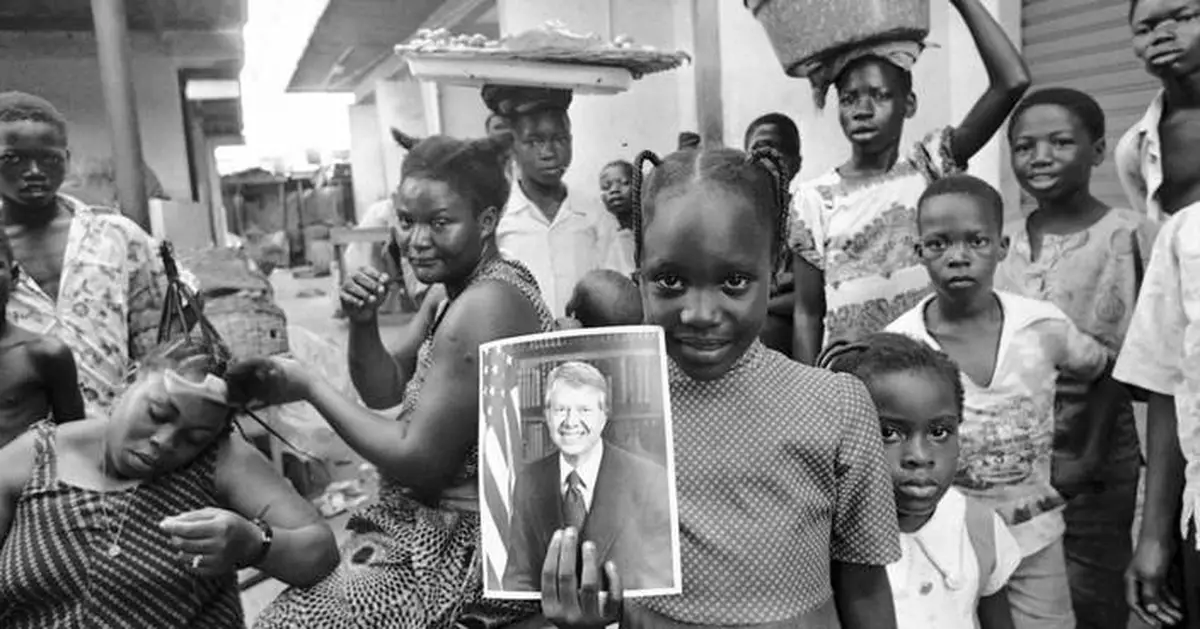

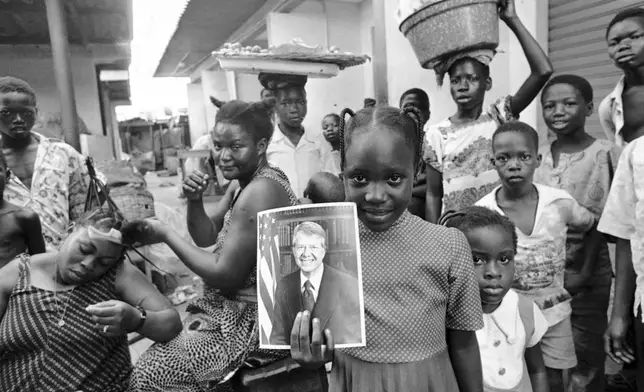

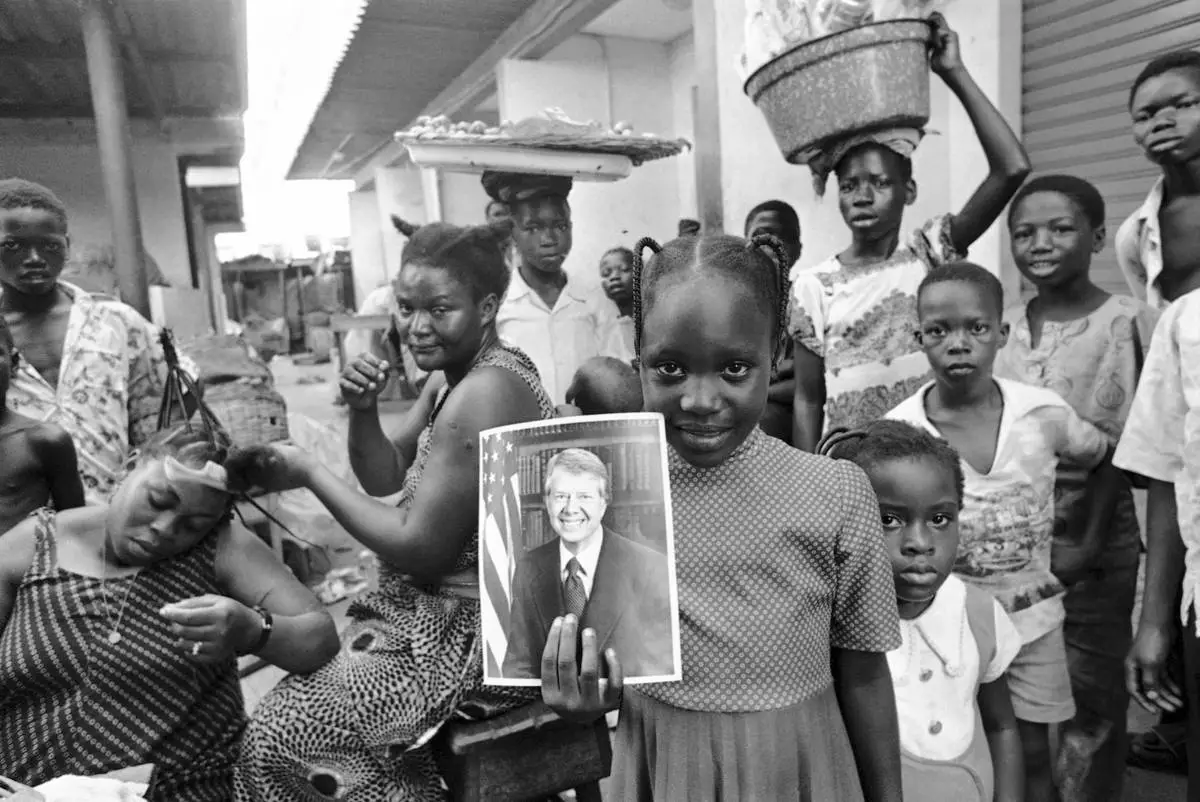

FILE - A girl holds a portrait of U.S. President Jimmy Carter in a market in Lagos, Nigeria, March 31, 1978, the day of his arrival for a state visit, the first to Africa by an American president. (AP Photo/Dieter Endlicher, File)

“I think the day of the so-called ugly American is over,” Carter said during his warm 1978 reception in Nigeria, Africa's most populous country. He said the official state visit swept aside “past aloofness by the United States,” and he joked that he and Nigerian President Olesegun Obasanjo would go into peanut farming together.

Cold War tensions drew Carter's attention to the continent as the U.S. and Soviet Union competed for influence. But Carter also drew on the missionary traditions of his Baptist faith and the racial injustice he witnessed in his homeland in the U.S. South.

“For too long our country ignored Africa,” Carter told the Democratic National Committee in his first year as president.

African leaders soon received invitations to the White House, intrigued by the abrupt interest from the world’s most powerful nation and what it could mean for them.

“There is an air of freshness which is invigorating," visiting Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda said.

Carter observed after his first Africa trip, “There is a common theme that runs through the advice to me of leaders of African nations: ‘We want to manage our own affairs. We want to be friends with both of the great superpowers and also with the nations of Europe. We don’t want to choose up sides.’”

The theme echoes today as China also jostles with Russia and the U.S. for influence, and access to Africa's raw materials. But neither superpower has had an emissary like Carter, who made human rights central to U.S. foreign policy and made 43 more trips to the continent after his presidency, promoting Carter Center projects that sought to empower Africans to determine their own futures.

As president, Carter focused on civil and political rights. He later broadened his efforts to include social and economic rights as the key to public health.

“They are the rights of the human by virtue of their humanity. And Carter is the single person in the world that has done the most for advancing this idea,” said Abdullahi Ahmed An-Naim, a Sudanese legal scholar.

Even as a candidate, Carter mused about what he might accomplish, telling Playboy magazine, “it might be that now I should drop my campaign for president and start a crusade for black-majority rule in South Africa or Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). It might be that later on, we’ll discover there were opportunities in our lives to do wonderful things and we didn’t take advantage of them.”

Carter welcomed Zimbabwe’s independence just four years later, hosting new Prime Minister Robert Mugabe at the White House and quoting the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

“Carter told me that he spent more time on Rhodesia than he did on the entire Middle East. And when you go into the archives and look at the administration, there is indeed more on southern Africa than the Middle East,” historian and author Nancy Mitchell said.

Relations with Mugabe’s government soon soured amid deadly repression, and by 1986 Carter led a walkout of diplomats in the capital. In 2008, Carter was barred from Zimbabwe, a first in his travels. He called the country “a basket case, an embarrassment to the region.”

“Whatever the Zimbabwean leadership may think of him now, Zimbabweans, at least those who were around in the 1970s and ’80s, will always regard him as an icon and a tenacious promoter of democracy,” said Eldred Masunungure, a Harare-based political analyst.

Carter also criticized South Africa’s government for its treatment of Black citizens under apartheid, at a time when South Africa was “trying to ingratiate itself with influential economies around the world,” current President Cyril Ramaphosa said on X after Carter’s death.

The think tank Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter founded in 1982 played a key role in monitoring African elections and brokering cease-fires between warring forces, but fighting disease was the third pillar of The Carter Center's work.

“The first time I came here to Cape Town, I almost got in a fight with the president of South Africa, Thabo Mbeki, because he was refusing to let AIDS be treated,” Carter told a local newspaper. “That’s the closest I’ve come to getting into a fist fight with a head of state.”

Carter often said he was determined to outlive the last guinea worm infecting the human race. Once affecting millions of people, the parasitic disease has nearly been eliminated, with just 14 cases documented in 2023 in a handful of African countries.

Carter's quest included arranging a four-month “guinea worm cease-fire” in Sudan in 1995 so that The Carter Center could reach almost 2,000 endemic villages.

“He taught us a lot about having faith,” said Makoy Samuel Yibi, who leads the guinea worm eradication program for South Sudan's health ministry and grew up with people who believed the disease was simply their fate. “Even the poor people call these people poor, you see. To have the leader of the free world pay attention and try to uplift them is a touching virtue.”

Such dedication impressed health officials in Africa over the years.

“President Carter worked for all humankind irrespective of race, religion, or status,” Ethiopia’s former health minister, Lia Tadesse, said in a statement shared with the AP. Ethiopia, the continent’s second most populous country with over 110 million people, had zero guinea worm cases in 2023.

Associated Press reporters Farai Mutsaka in Harare, Zimbabwe, and Michael Warren in Atlanta contributed.

FILE - Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter, right, greets Southern Sudanese men waiting to cast their vote at a polling station in Juba, Southern Sudan, Jan 9, 2011, during a weeklong referendum on independence that is expected to split Africa's largest nation in two. (AP Photo/Jerome Delay, File)

FILE - Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter helps in the contruction of a low-income housing project in Durban, South Africa, June 6, 2002. Carter was among 4,500 volunteers, organized by Habitat for Humanity, building 100 homes in the coastal city during the week. (AP Photo/Themba Hadebe, File)

FILE - Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter, left, speaks with Ethiopian President Mengistu Haile Mariam in Addis Ababa, July 11, 1990, during the 26th summit of the Organization of African Unity. (AP Photo/Aris Saris, File)

FILE - U.S. President Jimmy Carter reviews honor guards during arrival ceremonies at the Dodan Barracks in Lagos, Nigeria, April 1, 1978. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - President Jimmy Carter meets with Zimbabwean Prime Minister Robert Mugabe in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington, Aug. 27, 1980. (AP Photo/Barry Thumma, File)

FILE - Former South African President Nelson Mandela, left, and former U.S. President Jimmy Carter, right, hold HIV-positive babies at the Zola Clinic in Soweto, March 7, 2002. (AP Photo/Nonthemba Kwela, File)

FILE - A girl holds a portrait of U.S. President Jimmy Carter in a market in Lagos, Nigeria, March 31, 1978, the day of his arrival for a state visit, the first to Africa by an American president. (AP Photo/Dieter Endlicher, File)

WASHINGTON (AP) — It's the largest prosecution in Justice Department history — with reams of evidence, harrowing videos and hundreds of convictions of the rioters who stormed the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. Now Donald Trump's return to power has thrown into question the future of the more than 1,500 federal cases brought over the last four years.

Jan. 6 trials, guilty pleas and sentencings have continued chugging along in Washington's federal court despite Trump's promise to pardon rioters, whom he has called “political prisoners" and “hostages” he contends were treated too harshly.

In a statement Monday, Attorney General Merrick Garland said Justice Department prosecutors “have sought to hold accountable those criminally responsible for the January 6 attack on our democracy with unrelenting integrity.”

“They have conducted themselves in a manner that adheres to the rule of law and honors our obligation to protect the civil rights and civil liberties of everyone in this country,” Garland said.

Here's a look at where the prosecutions stand on the fourth anniversary of the Capitol riot and what could happen next:

More than 1,500 people across the U.S. have been charged with federal crimes related to the deadly riot. Hundreds of people who did not engage in destruction or violence were charged only with misdemeanor offenses for entering the Capitol illegally. Others were charged with felony offenses, including assault for beating police officers. Leaders of the Oath Keepers and the Proud Boys extremist groups were convicted of seditious conspiracy for what prosecutors described as plots to use violence to stop the peaceful transfer of power from Trump, a Republican, to Joe Biden, a Democrat.

About 250 people have been convicted of crimes by a judge or a jury after a trial. Only two people were acquitted of all charges by judges after bench trials. No jury has fully acquitted a Capitol riot defendant. At least 1,020 others had pleaded guilty as of Jan. 1.

More than 1,000 rioters have already been sentenced, with over 700 receiving at least some time behind bars. The rest were given some combination of probation, community service, home detention or fines.

The longest sentence, 22 years, went to former Proud Boys national chairman Enrique Tarrio, who was convicted of seditious conspiracy along with three lieutenants. A California man with a history of political violence got 20 years in prison for repeatedly attacking police with flagpoles and other makeshift weapons during the riot. And Oath Keepers founder Stewart Rhodes is serving an 18-year prison sentence for seditious conspiracy and other offenses.

More than 100 Jan. 6 defendants are scheduled to stand trial in 2025, while at least 168 riot defendants are set to be sentenced this year.

The FBI has continued to arrest people on Capitol riot charges since Trump’s electoral victory in November. The Justice Department says prosecutors are still evaluating nearly 200 riot cases investigated by the FBI, including more than 60 cases in which the suspects are accused of assaulting or interfering with police officers who were guarding the Capitol.

Citing Trump's promise of pardons, several defendants have sought to have their cases delayed — with little success.

In denying one such request, U.S. District Judge Royce Lamberth, who was nominated to the bench by President Ronald Reagan, a Republican, wrote: "This Court recently had the occasion to discuss what effect the speculative possibility of a presidential pardon has on the timetable for a pending criminal matter. In short: little to none."

One defendant who convinced a judge to postpone his trial, William Pope, told the court that the “American people gave President Trump a mandate to carry out the agenda he campaigned on, which includes ending the January 6 prosecutions and pardoning those who exercised First Amendment rights at the Capitol.” Pope has now asked the judge to allow him to travel to Washington to attend Trump's inauguration on Jan. 20.

Trump embraced the Jan. 6 rioters on the campaign trail, downplaying the violence that was broadcast on live TV and has been documented extensively through video, testimony and other evidence in the federal cases.

Trump has vowed to begin issuing pardons of Jan. 6 rioters on his first day in office. He has said he will look at individuals on a case-by-case basis, but he has not explained how he will decide who receives such relief.

He has said there may be “some exceptions" — if “somebody was radical, crazy." But he has not ruled out pardons for people convicted of serious crimes, like assaulting police officers. When confronted in a recent NBC News interview about the dozens of people who have pleaded guilty to assaulting law enforcement, Trump responded: “Because they had no choice."

In a letter dated Monday to Trump, a lawyer for Tarrio urged the president-elect to pardon the former Proud Boys leader, who was convicted of seditious conspiracy.

Many judges in Washington's federal court have condemned the depiction of the rioters as “political prisoners," and some have raised alarm about the potential pardons.

"No matter what ultimately becomes of the Capital Riots cases already concluded and still pending, the true story of what happened on January 6, 2021 will never change," Judge Lamberth recently said in a statement when handing down a sentence.

U.S. District Judge Carl Nichols, who was nominated to the bench by Trump, has said it would be “beyond frustrating and disappointing” if Trump hands out mass pardons to rioters.

In another case, U.S. District Judge Amit Mehta alluded to the prospect of a pardon for Rhodes, the Oath Keepers founder convicted of seditious conspiracy.

“The notion that Stewart Rhodes could be absolved of his actions is frightening and ought to be frightening to anyone who cares about democracy in this country,” said Mehta, who was nominated by President Barack Obama, a Democrat.

Follow the AP's coverage of the Jan. 6 insurrection at https://apnews.com/hub/capitol-siege.

FILE - Violent protesters loyal to President Donald Trump, including Kevin Seefried, center, holding a Confederate battle flag, are confronted by U.S. Capitol Police officers outside the Senate Chamber inside the Capitol, Jan. 6, 2021 in Washington. (AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta, File)

FILE - Supporters of President Donald Trump climb the west wall of the the U.S. Capitol in Washington, Jan. 6, 2021. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana, File)

FILE - A flag hangs between broken windows after then-President Donald Trump supporters tried to break through police barriers outside the U.S. Capitol, Jan 6, 2021. (AP Photo/John Minchillo, File)

FILE - Insurrectionists loyal to President Donald Trump try to break through a police barrier, Wednesday, Jan. 6, 2021, at the Capitol in Washington. (AP Photo/Julio Cortez, File)