PLAINS, Ga. (AP) — When Jimmy Carter chose branding designs for his presidential campaign, he passed on the usual red, white and blue. He wanted green.

Emphasizing how much the Georgia Democrat enjoyed nature and prioritized environmental policy, the color became ubiquitous. On buttons, bumper stickers, brochures, the sign rechristening the old Plains train depot as his campaign headquarters. Even the hometown Election Night party.

“The minute it was announced, we all had the shirts to put on — and they were green, too,” said LeAnne Smith, Carter’s niece, recalling the 1976 victory celebration.

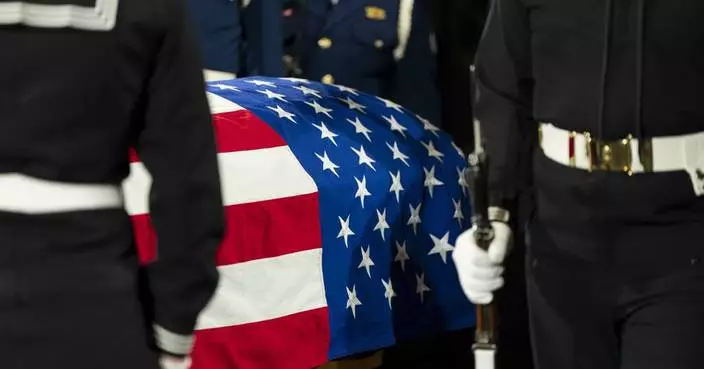

Nearly a half-century later, environmental advocates are remembering Carter, who died on Dec. 29 at the age of 100, as a president who elevated environmental stewardship, energy conservation and discussions about the global threat of rising carbon dioxide levels.

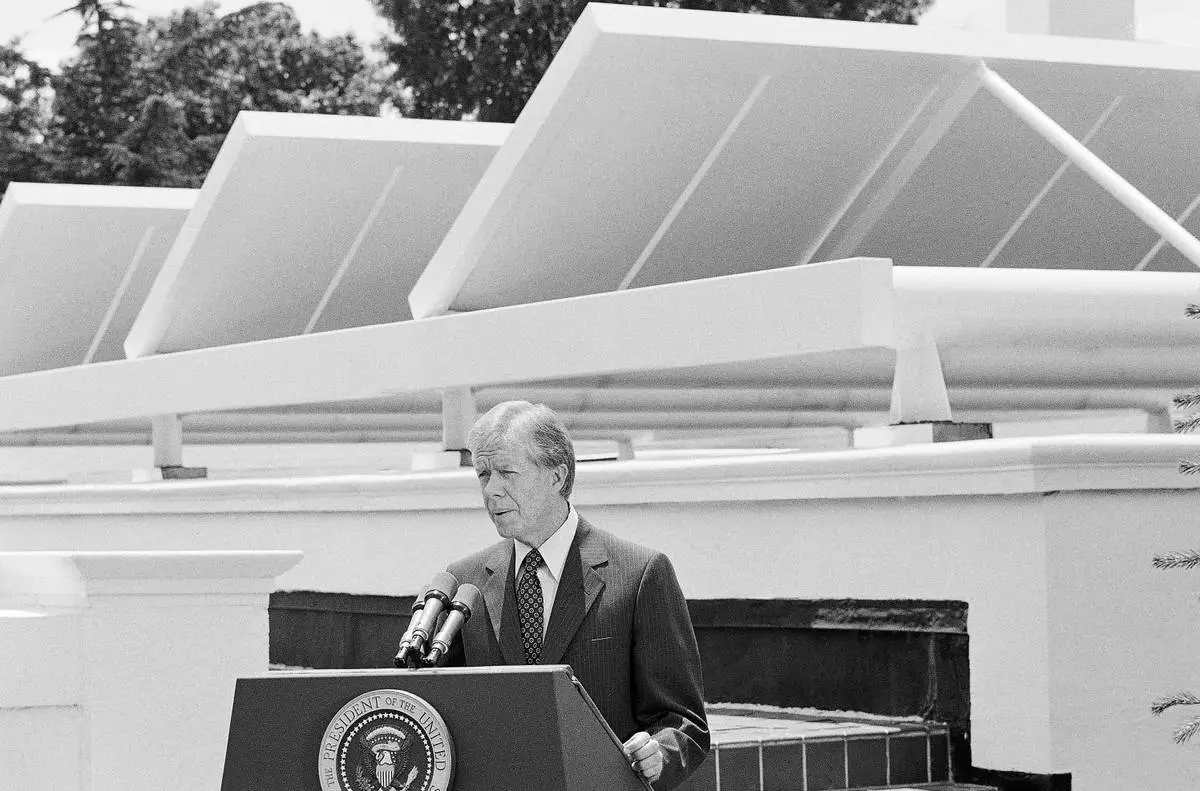

President-elect Donald Trump has vowed to abandon the renewable energy investments that President Joe Biden included in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, echoing how President Ronald Reagan dismantled the solar panels Carter installed on the White House roof. But politics aside, the scientific consensus has settled where Carter stood two generations earlier.

“President Carter was four decades ahead of his time,” said Manish Bapna, who leads the Natural Resources Defense Council. Carter called for cuts in greenhouse gas emissions well before “climate change” was part of the American lexicon, he said.

Former Vice President Al Gore, whose climate advocacy earned him the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize, called Carter “a lifelong role model for the entire environmental movement.”

As president, Carter implemented the first U.S. efficiency standards for passenger vehicles and household appliances. He created the U.S. Department of Energy, which streamlined energy research, and more than doubled the wildnerness area under National Park Service protection.

Inviting ridicule, Carter asked Americans to conserve energy through personal sacrifice, including driving less and turning down thermostats in winter amid global fuel shortages. He pushed renewable energy to lessen dependence on fossil fuels, calling for 20% of U.S. energy to come from alternative sources by 2000.

But laments linger about what 39th president could not get done or did not try before his landslide defeat to Ronald Reagan.

Carter left office in 1981 shortly after receiving a West Wing report linking fossil fuels to rising carbon dioxide levels in Earth’s atmosphere. Carter’s top environmental advisers urged “immediate” cutbacks on the burning of fossil fuels to reduce what scientists at the time called “carbon dioxide pollution.”

“Nobody anywhere in the world in a high government position was talking about this problem” before Carter, biographer Jonathan Alter said.

The White House released the findings, which drew forgettable news coverage: The New York Times published its story on the 13th page of its front section. And with scant time left in office, there were no tangible moves Carter could make, beyond the energy legislation he had already signed.

The report recommended limiting global average temperatures to 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial levels. Thirty-five years later, in the 2015 Paris climate accords, participating nations set a similar goal.

“If he had been reelected, it’s fair to say that we would have been beginning to address climate change in the early 1980s,” Alter told the AP. “When you think about that, it adds a kind of a tragic dimension, almost, to his political defeat.”

Reagan ended high-level conversations about carbon emissions. He opposed efficiency standards as government overreach and rolled back some regulations. His chief of staff, Don Regan, called the solar panels “a joke.”

Despite Carter’s emphasis on renewable sources, the fossil fuel industry benefited from his push toward U.S. energy independence.

Collin O’Mara, CEO of the National Wildlife Foundation, pointed to coal-fired power plants built during and shortly thereafter Carter’s term, and his deregulation of natural gas production, a move O'Mara called “a precursor” to widespread fracking. Bapna noted Carter backed drilling off the coasts of Long Island in New York and New England.

Steven Nadel, executive director of the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, pointed to Carter’s Synthetic Fuels Corporation, a short-lived effort to produce fossil fuel alternatives that “would have meant much higher carbon emissions.”

But Carter had the right priorities, especially on research and development coordinated through the Energy Department, Nadel said. “He allowed us to have a national approach rather than one agency here and another there."

Carter’s environmental interests had deep roots going back to a a rural boyhood filled with hunting and fishing and working his father’s farmland.

“Jimmy Carter was an environmentalist before it was a real part of the political discussion — and I’m not talking about solar panels on the White House,” said Dubose Porter, a longtime Georgia Democratic Party leader. “Just focusing on that misses how early and how committed he was.”

His early years influenced Carter as governor, Porter said, when he boosted Georgia's state parks system and opposed Georgia congressmen who wanted to dam a river. Carter paddled the waterway himself and decided its natural state trumped the lucrative federal construction proposal.

In Washington, Carter continued sometimes unwinnable fights against funding for projects he deemed damaging and unnecessary. He found more success extending federal protection for more than 150 million acres (60.7 million hectares), including redwood forests in California and vast swaths of Alaska.

Randall Balmer, a Dartmouth College professor who has written on Carter's faith, said he saw himself as a custodian of divinely granted natural resources.

“That’s a real connection that young evangelicals still have with him today,” Balmer said.

Carter won the presidency amid energy shortages rooted in global strife, especially in the oil-rich Middle East, so national security and economic interests dovetailed with Carter’s religious beliefs and affinity for nature, Nadel noted.

Carter compared the energy crisis to “the moral equivalent of war,” and as inflation and gas lines grew, he called for individual sacrifice and sweeping action on renewable energy.

“Human identity is no longer defined by what one does, but by what one owns,” Carter warned in 1979. “But we’ve discovered that owning things and consuming things does not satisfy our longing for meaning.”

That “malaise” speech — dubbed so by the media despite Carter not using the word — was unique in presidential politics for its condemnation of unchecked American consumerism. Carter celebrated that more than 100 million Americans watched. By 2010, Carter acknowledged in his annotated “White House Diary” that his speech was a flop, but said it proved to be prescient for advocating bold and direct action on energy.

“You can say the Carter presidency is still producing results today,” said Washington Gov. Jay Inslee, whose 2020 presidential run focused on climate action. “I’ve learned in politics that timing is everything and serendipity is everything.”

Former Associated Press reporter Drew Costley contributed from Washington, D.C.

FILE - Former President Jimmy Carter, center, sits with his grandson Jason Carter, left, and George Mori, executive vice president at SolAmerica Energy during a ribbon cutting ceremony for a solar panel project on Jimmy Carter's farmland in his hometown of Plains, Ga., Feb. 8, 2017. (AP Photo/David Goldman, File)

FILE - President Jimmy Carter talks to power plant workers against a backdrop of tall stacks at the Louisville Gas and Electric Company plant in Louisville, Ky., July 31, 1979. (AP Photo, File)

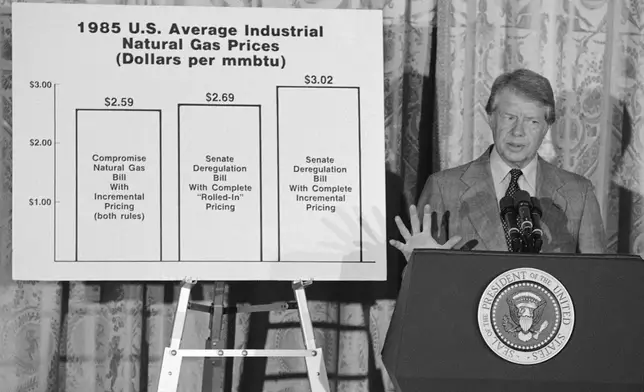

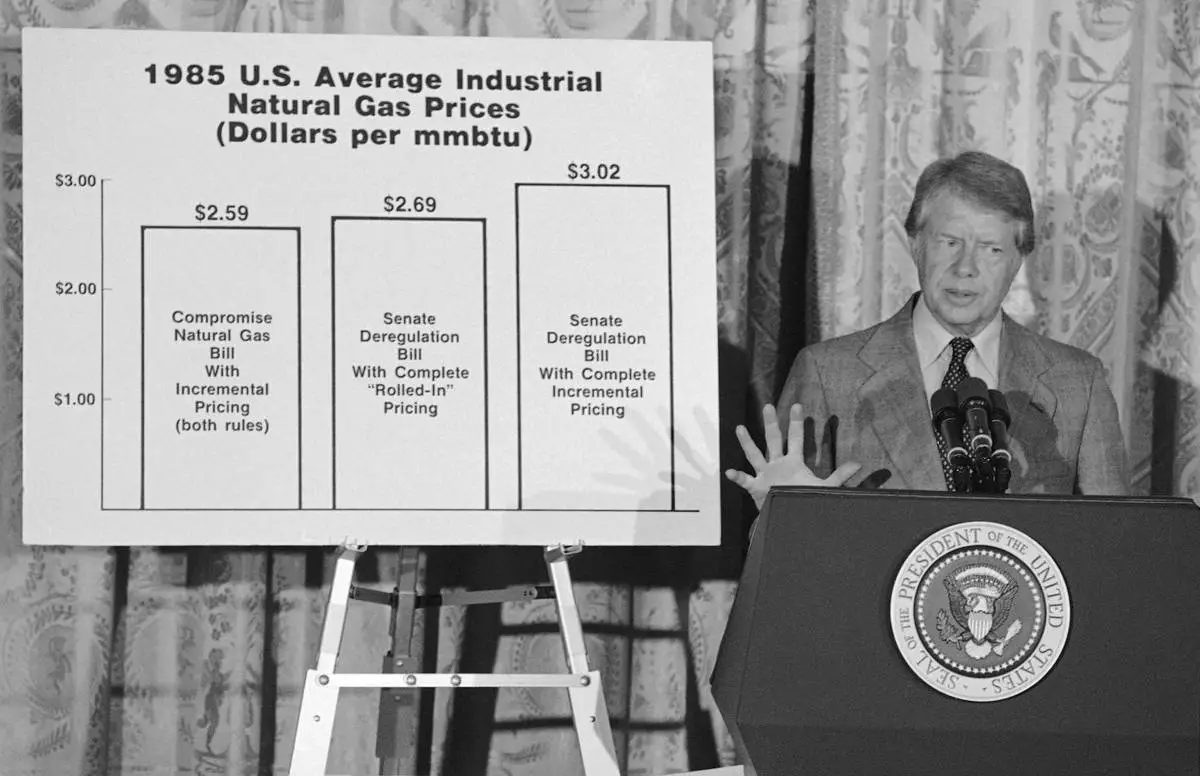

FILE - President Jimmy Carter speaks to executives of gas-using businesses at the White House in Washington, Aug. 31, 1978, before the passage of a natural gas compromise bill. (AP Photo/Jeff Taylor, File)

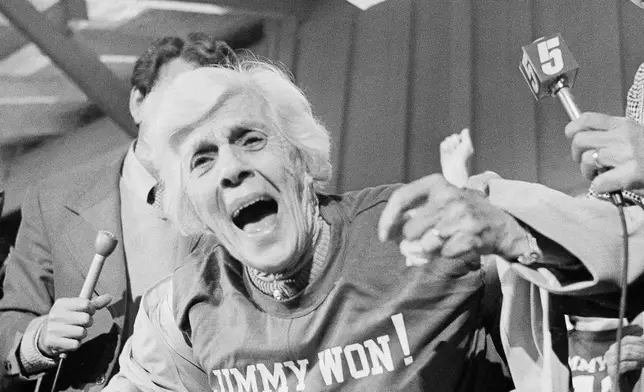

FILE - Lillian Carter, mother of Jimmy Carter, displays her "Jimmy Won!" T-shirt at a train station after Carter was declared the winner in the presidential election, Nov. 3, 1976, in Plains, Ga. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - President Jimmy Carter speaks against a backdrop of solar panels at the White House, June 21, 1979, in Washington. (AP Photo/Harvey Georges, File)