CALGARY, Alberta (AP) — Al MacNeil, a former NHL player who won the Stanley Cup as coach of the Montreal Canadiens, has died. He was 89.

The Calgary Flames announced Monday that MacNeil died a day earlier in Calgary. No cause of death was provided.

MacNeil was a defenseman who played 524 NHL games for the Toronto Maple Leafs, Canadiens, Chicago Blackhawks, New York Rangers and Pittsburgh Penguins between 1955 and 1968.

He compiled 17 goals, 75 assists and 615 penalty minutes during his player career.

He was a first-year coach of the Canadiens when the team won the Stanley Cup in 1971. MacNeil was Montreal’s director of player personnel for Stanley Cup wins in 1978 and 1979.

MacNeil won three Calder Cups as general manager and head coach of the Canadiens’ farm team, the Nova Scotia Voyageurs, in 1972, 1976 and 1977.

MacNeil, from Sydney, Nova Scotia, was the last coach of the Atlanta Flames and the first coach of the Calgary Flames for their first two seasons after relocation. He was an assistant general manager of the Flames for their Stanley Cup victory in 1989.

“Al was a great man who will be dearly missed by our organization,” Calgary Sports and Entertainment Corporation chairman Murray Edwards said in a statement. “He was a long-term loyal member of our Flames family ever since the team’s arrival in Calgary in 1980. He played, coached, and managed in both the NHL and AHL, and had ultimate success while doing so.”

He was also interim head coach of the Flames for 13 games in 2002-03.

He was an assistant coach of Canada’s team that won the 1976 Canada Cup, and served in that role again at the 1981 Canada Cup.

“For the last 70 years, Al MacNeil’s impact on our game has been profound, both on and off the ice,” NHL commissioner Gary Bettman said in a statement. “First as a player, then as a coach, and finally as an executive, Al was the consummate professional who conducted himself with humility and grace.”

MacNeil is survived by his wife Norma, son Allister, who is an amateur scout for Flames, daughter Allison, son-in-law Paul Sparkes and grandsons Jack and Ben Sparkes.

AP NHL: https://apnews.com/hub/nhl

FILE - Detroit Red Wings' star Gordie Howe (9) charges in but is ganged up on the three Chicago players, Al MacNeil (19), Doug Jarrett (20), and goalie Glenn Hall, who defend against the shot in first period of their NHL game in Chicago, March 16, 1966. (AP Photo/Paul Cannon, File)

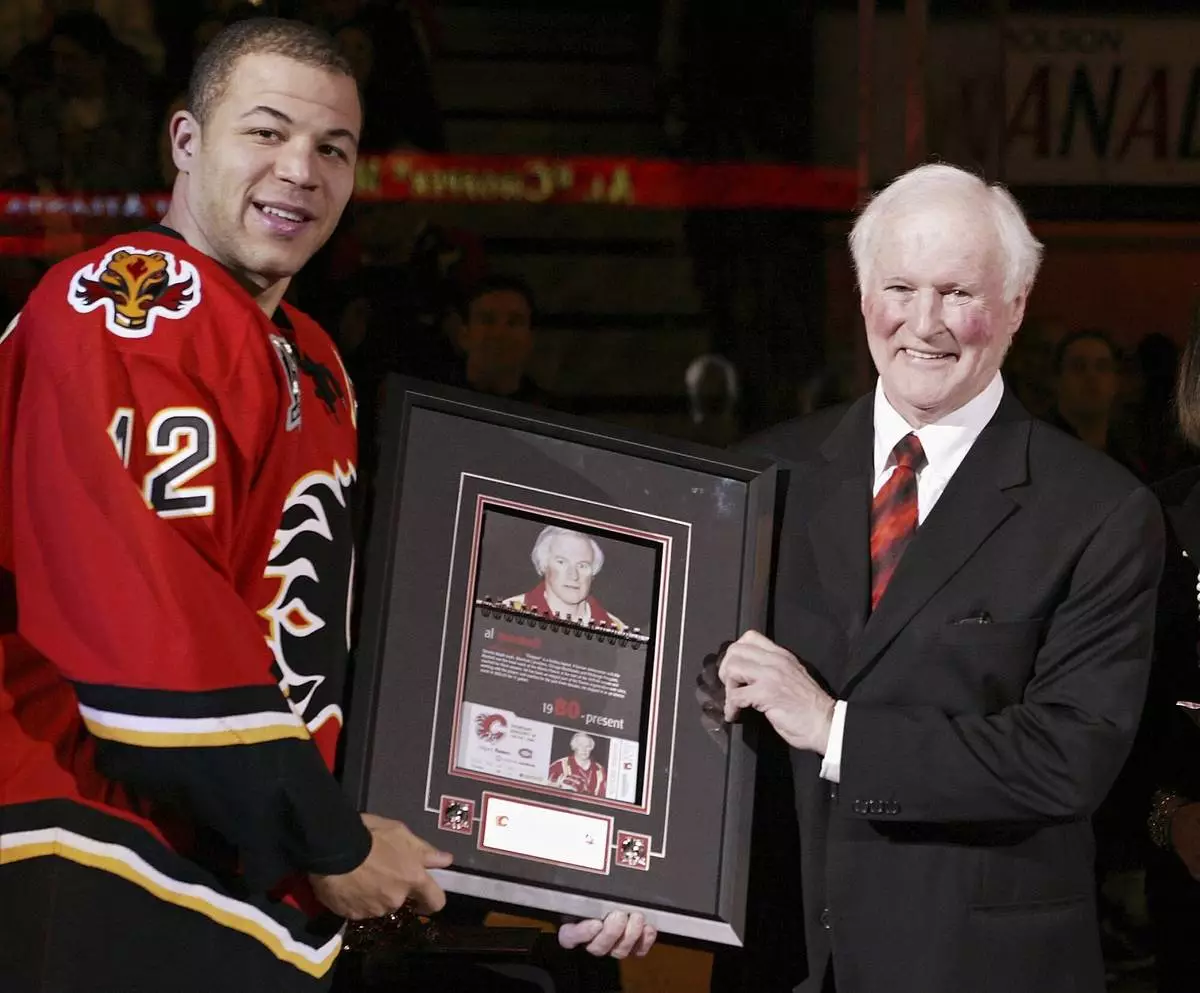

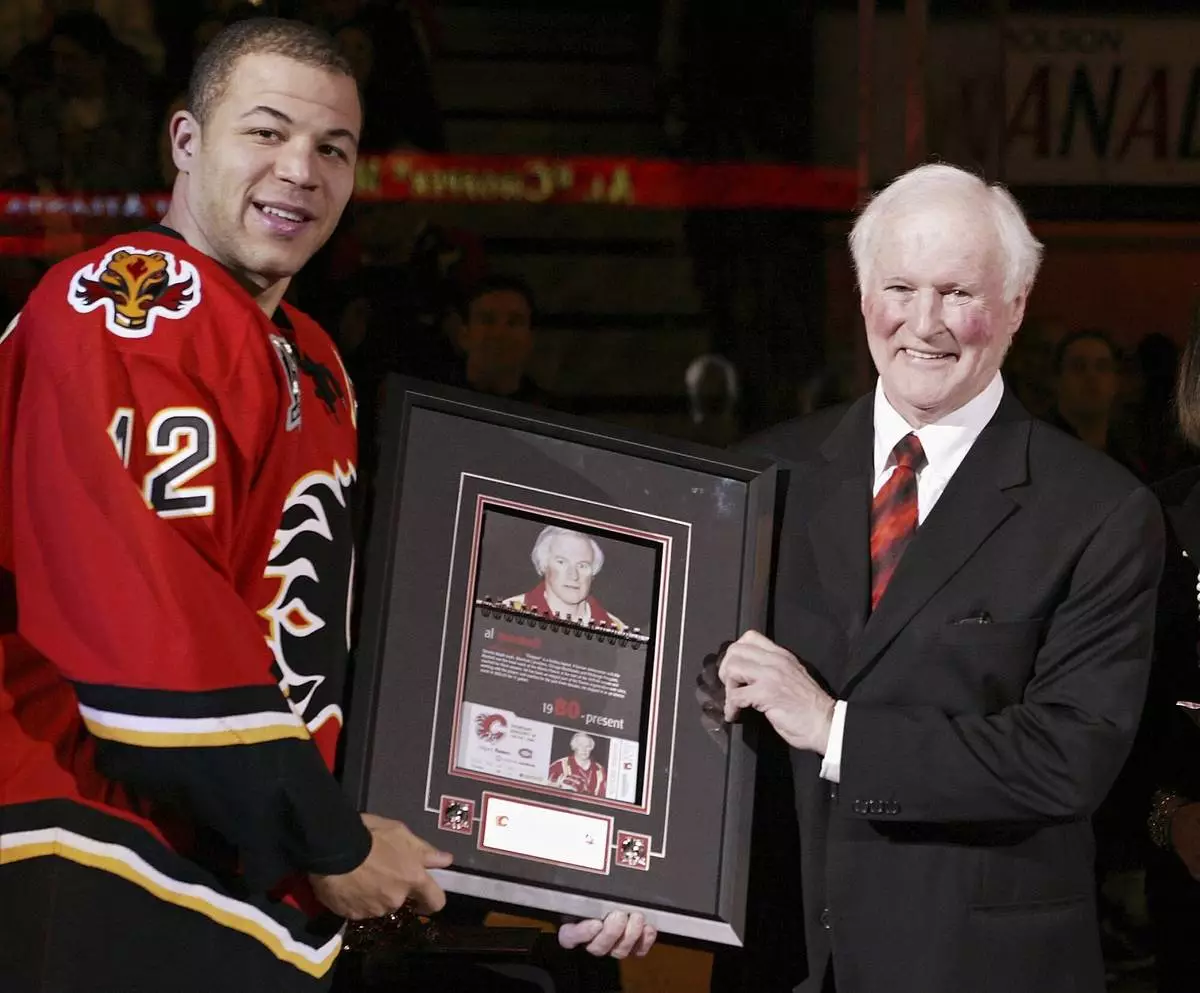

FILE - Calgary Flames captain Jarome Iginla, left, presents longtime Flames employee Al MacNeil with a plaque before the start NHL hockey action against the Montreal Canadiens in Calgary, Canada, Jan. 19, 2006. (Canadian Press/Jeff McIntosh, via AP, FILE)

FILE - Calgary Flames head coach Al MacNeil raises his arms in victory as time runs out in the Flames' 2-1 victory over the Colorado Avalanche in the Pepsi Center in Denver, Dec. 3, 2002. (AP Photo/David Zalubowski, File)

WELLINGTON, New Zealand (AP) — Wild weather during New Zealand ’s peak summer holiday period has disrupted travel for thousands of passengers on ferries that cross the sea between the country’s main islands.

The havoc wrought by huge swells and gales in the deep and turbulent Cook Strait between the North and South Islands is a recurring feature of the country’s roughest weather. Breakdowns of New Zealand’s aging ferries have also caused delays.

But unlike in Britain and Japan, New Zealand has not seriously considered an undersea tunnel beneath the strait that more than 1 million people cross by sea each year. Although every New Zealander has an opinion on the idea, the last time a prime minister was known to have suggested building one was in 1904.

A tunnel or bridge crossing the approximately 25-30 kilometers (15-18 miles) of volatile sea is so unlikely for the same reason that regularly vexes the country’s planners — solutions for traversing New Zealand’s remote, rugged and hazard-prone terrain are logistically fraught, analysts said.

A Cook Strait tunnel would dramatically reduce the three- to four-hour sailing time between the North Island, home to 75% of the population, and the South.

“But it would chew up, off the top of my head, about 20 years of the country’s entire transport infrastructure development budget in one project,” said Nicolas Reid, transport planner at MRCagney.

He estimated a cost for a tunnel of 50 billion New Zealand dollars ($28 billion), comparable in today’s terms to the price of the undersea tunnel that connects Britain and Europe by rail. New Zealand is the same size as the United Kingdom — but the U.K. has a population of 69 million, more than 13 times New Zealand’s.

It’s also about the same size as Japan, which is home to the Seikan undersea rail tunnel connecting the islands of Honshu and Hokkaido — and has a population of 124 million.

“We have a large infrastructure burden if we want to reach out across the country,” said Reid. “And we’ve only got 5 million people to pay for it.”

New Zealand’s volatile ground could also prove a problem. Perched on the boundary between tectonic plates, fault lines run under both the North and South Islands and earthquakes are sometimes centered in the strait, said seismologist John Risteau of GNS.

Sailing on both Cook Strait ferry services — which have five ships transporting people, vehicles and freight — resumed Tuesday after two days of dangerous waves. Clearing the backlog meant more waiting and some passengers on one carrier said they could not book a new berth for a fortnight.

The Cook Strait is less calm than many worldwide because it features opposing tides at each end — one where it joins the Tasman Sea and the other where it meets the Pacific Ocean.

“We tend to have the prevailing, dominating wind funnel through Cook Strait, northerlies or southerlies, and that’s why they’re stronger there,” said Gerard Bellam, a forecaster for the weather agency MetService. Swells in the strait this week reached 9 meters (30 feet), he said.

Julia Rufey, an English tourist waiting at the Wellington terminal, said she had flown between North Island and South Island on previous trips, but “adventure” had prompted her to choose the ferry.

“We thought, come to Wellington, try the ferry, which is already 3 1/2 hours late,” she said.

The ferries themselves, prone to breakdowns and more than half of them state-owned, have long been a political hot potato. The current government scrapped their predecessors’ plan to replace the vessels before they become defunct in 2029 as too costly. The opposition has criticized the government for only partly revealing its new ferry replacement plan in December and for not divulging the cost.

Still, some delayed on Tuesday said they would choose the ferry even if they had alternatives. Laurie Perino, an Australian tourist, said the pristine and scenic ocean views had prompted her to book.

“It would be more convenient,” she said, referring to a Cook Strait tunnel. “But I think a lot of people would still like to travel on the ferry.”

An Interislander ferry leaves Wellington harbor, New Zealand, on Tuesday, Jan. 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Charlotte Graham-McLay)

An Interislander ferry arrives in Wellington harbor, New Zealand, on Tuesday, Jan. 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Charlotte Graham-McLay)

Cars board an Interislander ferry in Wellington, New Zealand, on Tuesday, Jan. 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Charlotte Graham-McLay)

A ferry is docket, top right, in Wellington's harbor, New Zealand, on Tuesday, Jan. 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Charlotte Graham-McLay)

Bluebridge ferry passengers disembark in Wellington, New Zealand, on Tuesday, Jan. 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Charlotte Graham-McLay)