NEW YORK (AP) — President-elect Donald Trump was sentenced Friday to no punishment in his historic hush money case, a judgment that lets him return to the White House unencumbered by the threat of a jail term or a fine.

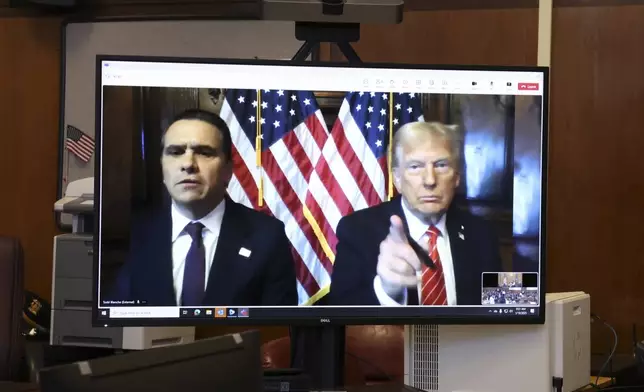

With Trump appearing by video from his Florida estate, the sentence quietly capped an extraordinary case rife with moments unthinkable in the U.S. only a few years ago.

Click to Gallery

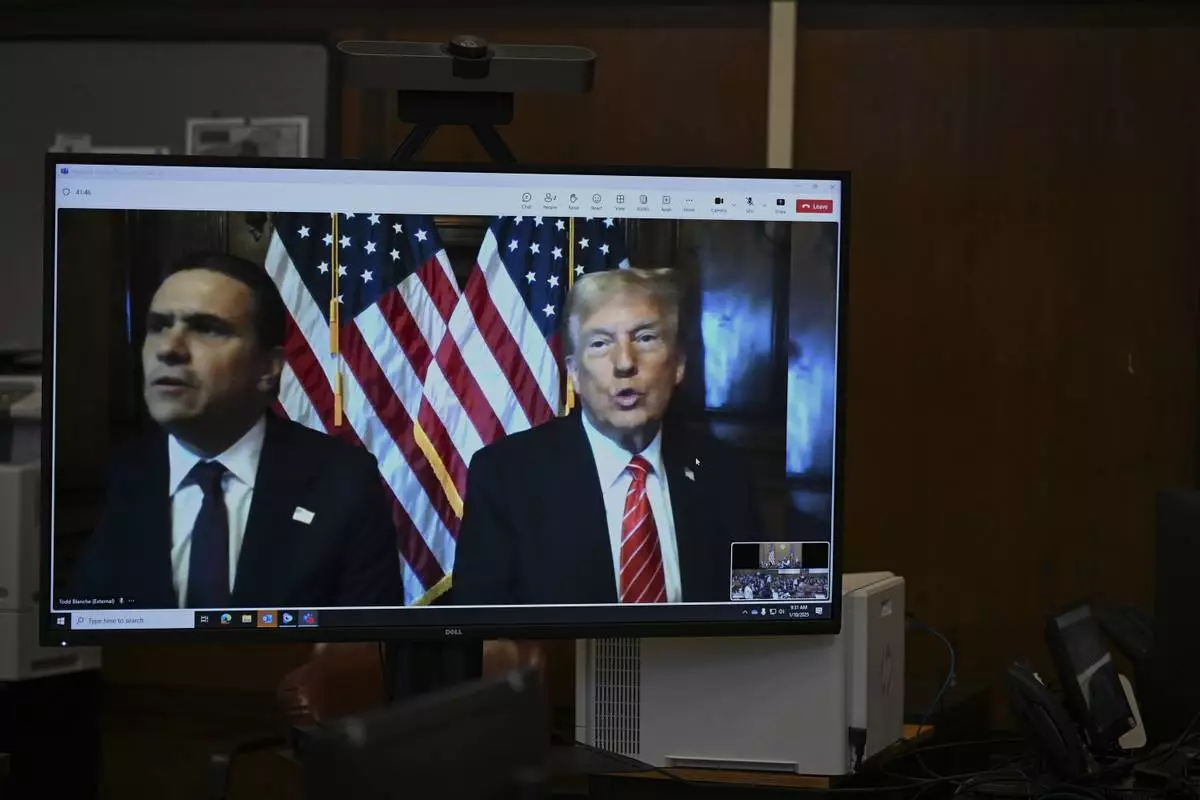

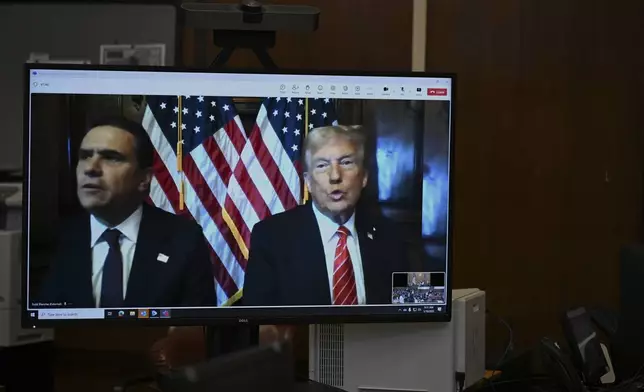

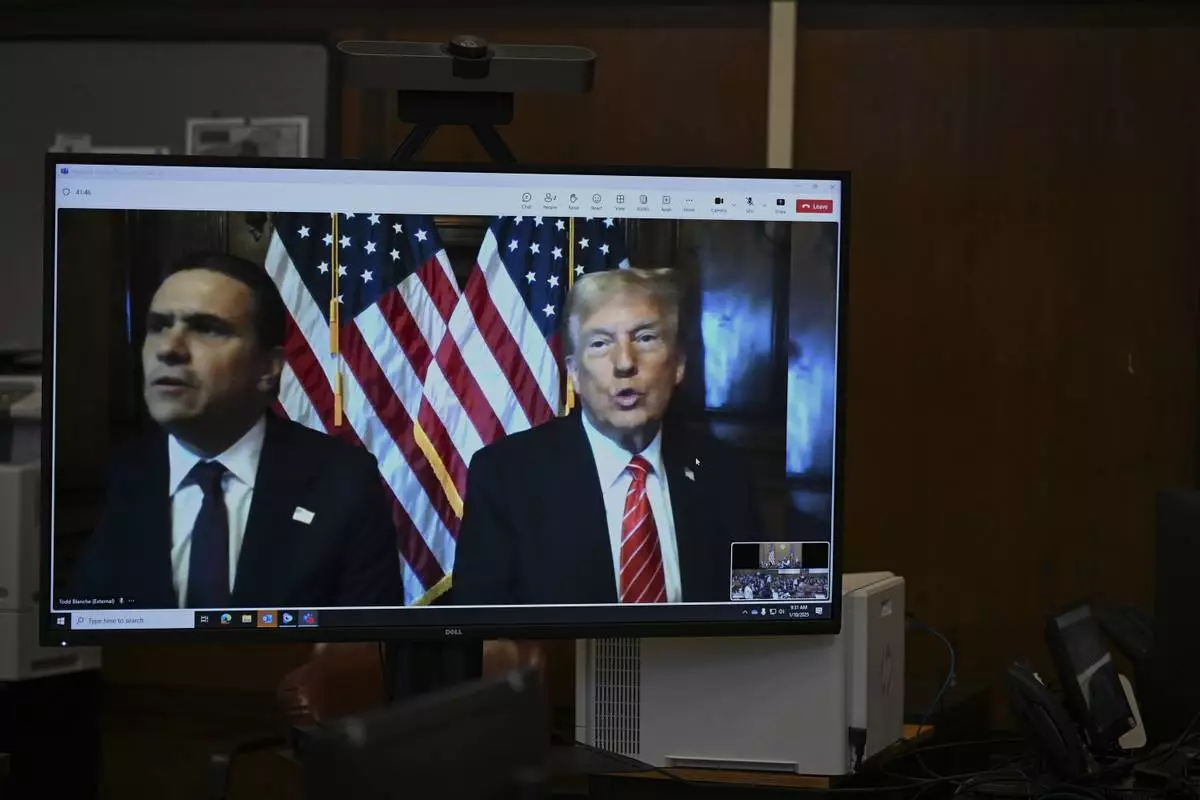

President-elect Donald Trump appears on a video feed for his sentencing for for his hush money conviction in a Manhattan courtroom on Friday, Jan. 10, 2025 in New York. (Curtis Means/Pool Photo via AP)

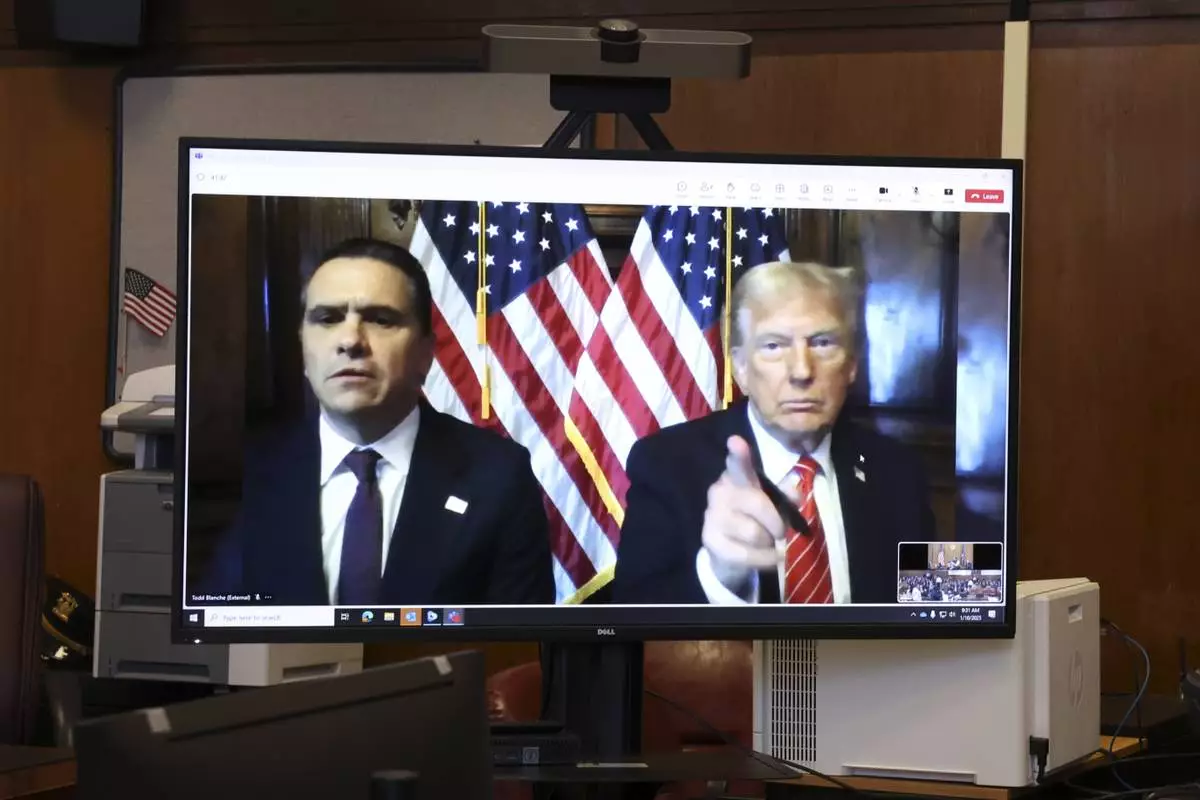

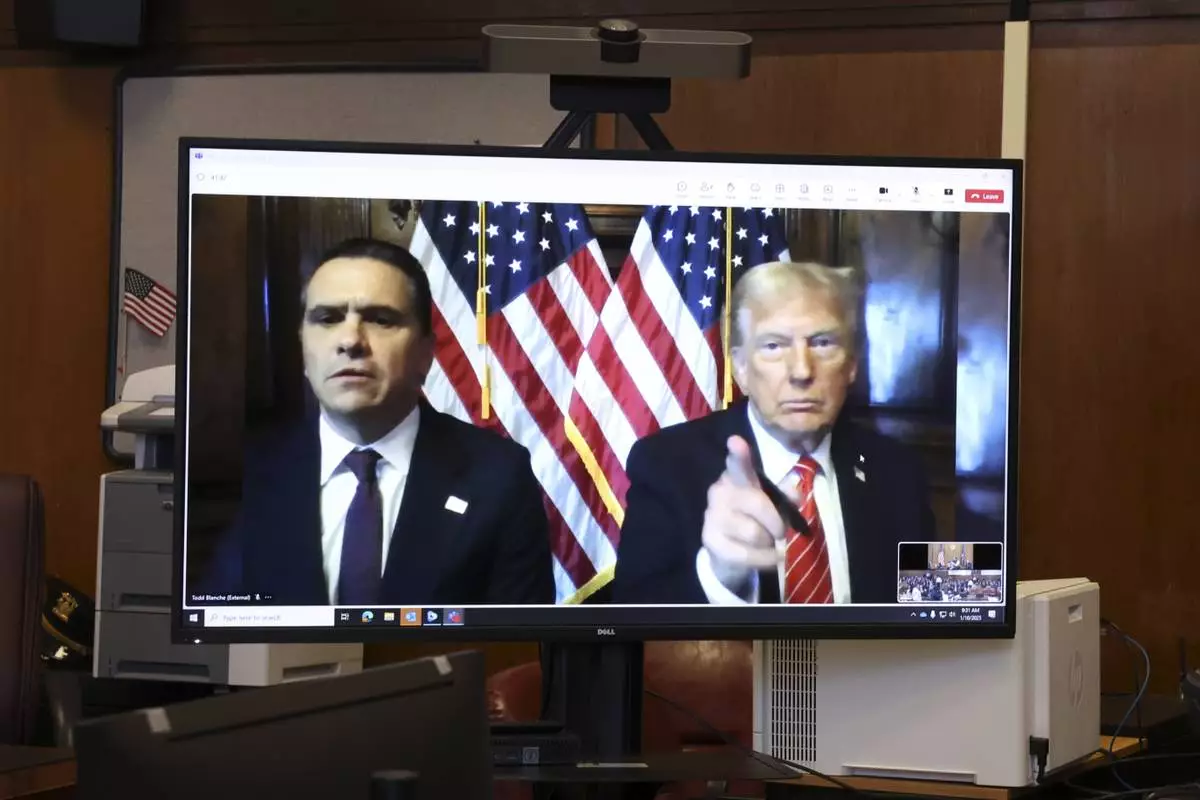

Attorney Emil Bove, left, listens as attorney Todd Blanche and President-elect Donald Trump, seen on a television screen, appear virtually for sentencing for Trump's hush money conviction in a Manhattan courtroom on Friday, Jan. 10, 2025 in New York. (Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post via AP, Pool)

Attorney Todd Blanche and President-elect Donald Trump, seen on a television screen, appear virtually for sentencing for Trump's hush money conviction in a Manhattan courtroom on Friday, Jan. 10, 2025 in New York. (Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post via AP, Pool)

President-elect Donald Trump appears on a video feed for his sentencing for for his hush money conviction in a Manhattan courtroom on Friday, Jan. 10, 2025 in New York. (Curtis Means/Pool Photo via AP)

U.S. President-elect Donald Trump appears remotely for a sentencing hearing in front of New York State Judge Juan Merchan in the criminal case in which he was convicted in 2024 on charges involving hush money paid to a porn star, at New York Criminal Court in Manhattan in New York, Jan. 10, 2025. (Brendan McDermid via AP, Pool)

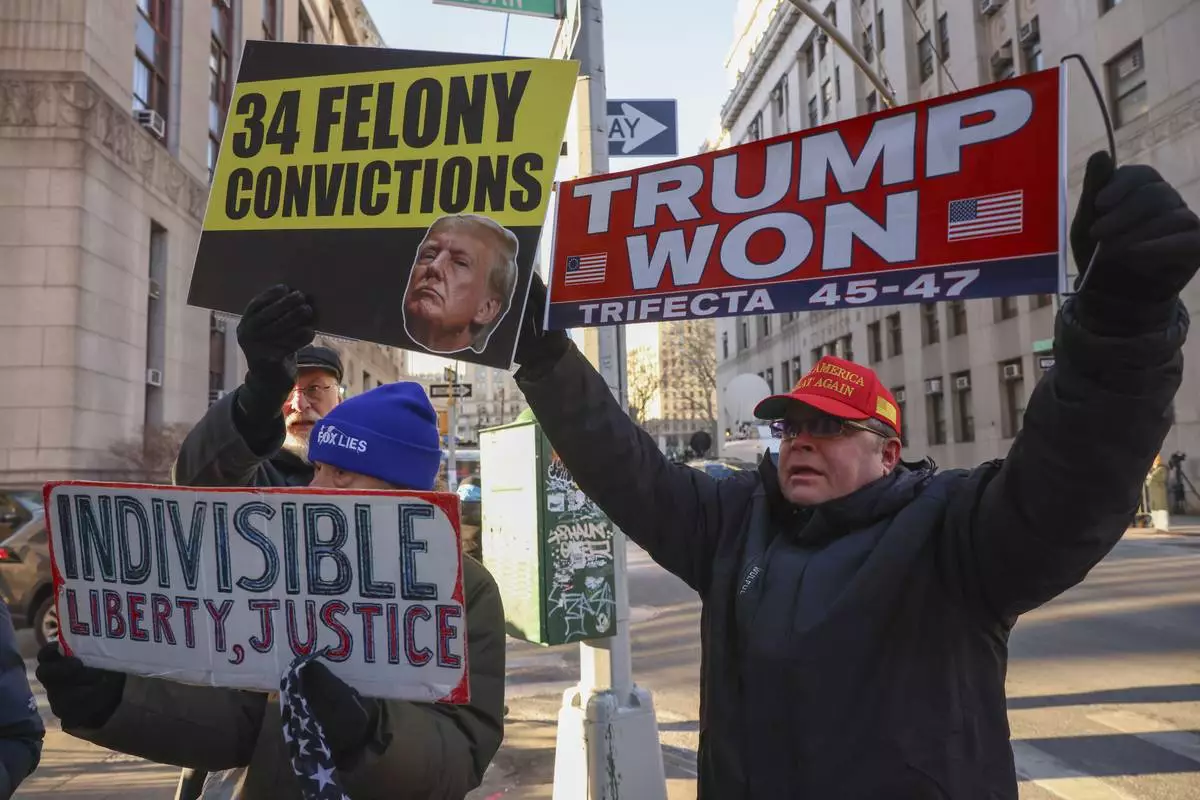

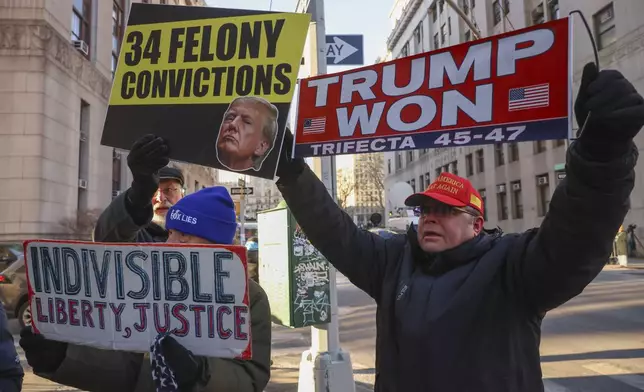

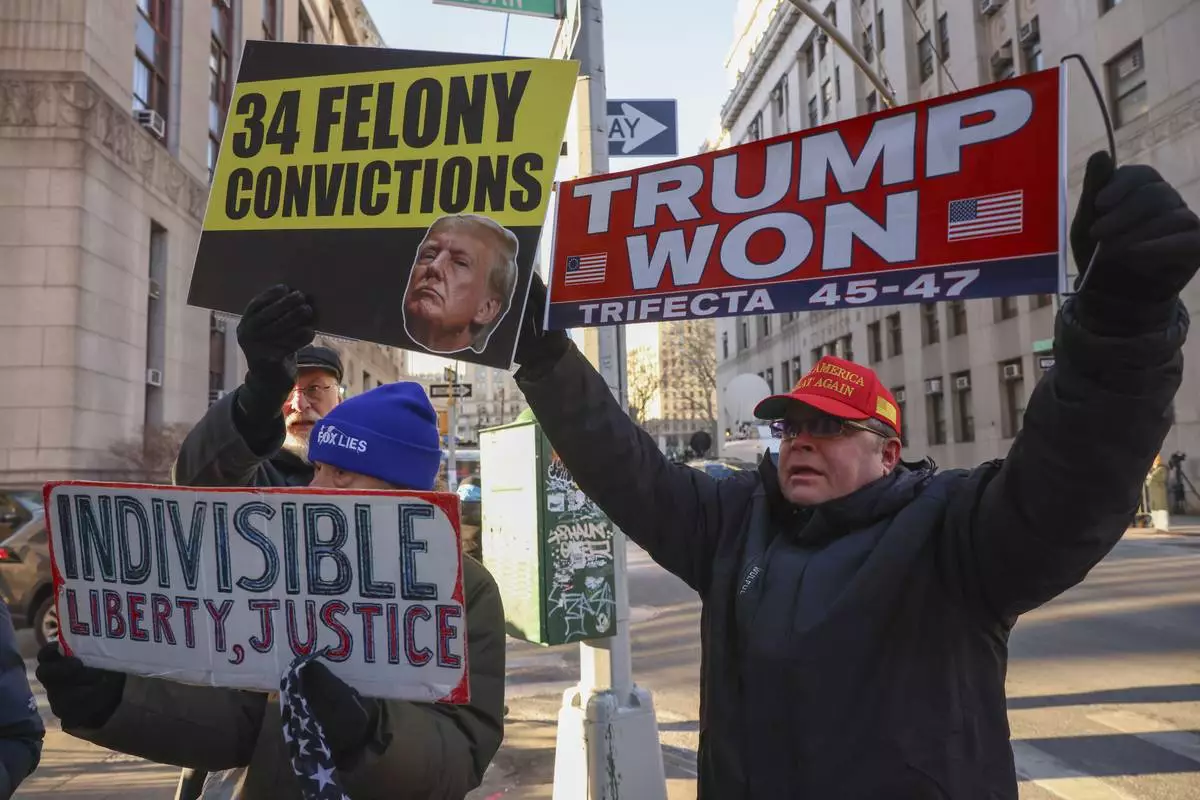

Demonstrators protest outside Manhattan criminal court before the start of the sentencing in President-elect Donald Trump's hush money case, Friday, Jan. 10, 2025, in New York. (AP Photo/Yuki Iwamura)

Demonstrators protest outside Manhattan criminal court before the start of the sentencing in President-elect Donald Trump's hush money case, Friday, Jan. 10, 2025, in New York. (AP Photo/Yuki Iwamura)

Demonstrators protest outside Manhattan criminal court before the start of the sentencing in President-elect Donald Trump's hush money case, Friday, Jan. 10, 2025, in New York. (AP Photo/Yuki Iwamura)

Demonstrators protest outside Manhattan criminal court before the start of the sentencing in President-elect Donald Trump's hush money case, Friday, Jan. 10, 2025, in New York. (AP Photo/Yuki Iwamura)

A man impersonating President-elect Donald Trump walks outside Manhattan criminal court before the start of the sentencing in Trump's hush money case, Friday, Jan. 10, 2025, in New York. (AP Photo/Yuki Iwamura)

A supporter for President-elect Donald Trump takes a photo of the Manhattan criminal courthouse before the start of the sentencing in Trump's hush money case, Friday, Jan. 10, 2025, in New York. (AP Photo/Yuki Iwamura)

A man crosses the street outside Manhattan criminal court before the start of the sentencing in President-elect Donald Trump's hush money case, Friday, Jan. 10, 2025, in New York. (AP Photo/Yuki Iwamura)

FILE - Judge Juan M. Merchan sits for a portrait in his chambers in New York, March 14, 2024. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig, File)

It was the first criminal prosecution and first conviction of a former U.S. president and major presidential candidate. The New York case became the only one of Trump's four criminal indictments that has gone to trial and possibly the only one that ever will. And the sentencing came 10 days before his inauguration for his second term.

In roughly six minutes of remarks to the court, a calm but insistent Trump called the case “a weaponization of government” and “an embarrassment to New York.” He maintained that he did not commit any crime.

"It’s been a political witch hunt. It was done to damage my reputation so that I would lose the election, and, obviously, that didn’t work,” the Republican president-elect said by video, with U.S. flags in the background.

After the roughly half-hour proceeding, Trump said in a post on his social media network that the hearing had been a “despicable charade.” He reiterated that he would appeal his conviction.

Manhattan Judge Juan M. Merchan could have sentenced the 78-year-old to up to four years in prison. Instead, Merchan chose a sentence that sidestepped thorny constitutional issues by effectively ending the case but assured that Trump will become the first president to take office with a felony conviction on his record.

Trump’s no-penalty sentence, called an unconditional discharge, is rare for felony convictions. The judge said that he had to respect Trump's upcoming legal protections as president, while also giving due consideration to the jury's decision.

“Despite the extraordinary breadth of those protections, one power they do not provide is the power to erase a jury verdict,” said Merchan, who had indicated ahead of time that he planned the no-penalty sentence.

As Merchan pronounced the sentence, Trump sat upright, lips pursed, frowning slightly. He tilted his head to the side as the judge wished him “godspeed in your second term in office.”

Before the hearing, a handful of Trump supporters and critics gathered outside. One group held a banner that read, “Trump is guilty.” The other held one that said, “Stop partisan conspiracy” and “Stop political witch hunt.”

Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg, whose office brought the charges, is a Democrat.

The norm-smashing case saw the former and incoming president charged with 34 felony counts of falsifying business records, put on trial for almost two months and convicted by a jury on every count. Yet the legal detour — and sordid details aired in court of a plot to bury affair allegations — didn’t hurt him with voters, who elected him in November to a second term.

Beside Trump as he appeared virtually Friday from his Mar-a-Lago property was defense lawyer Todd Blanche, with partner Emil Bove in the New York courtroom. Trump has tapped both for high-ranking Justice Department posts.

Prosecutors said that they supported a no-penalty sentence, but they chided Trump's attacks on the legal system throughout the case.

“The once and future president of the United States has engaged in a coordinated campaign to undermine its legitimacy,” prosecutor Joshua Steinglass said.

Afterward, Trump was expected to return to the business of planning for his new administration. He was set later Friday to host conservative House Republicans as they gathered to discuss GOP priorities.

The specific charges in the hush money case were about checks and ledgers. But the underlying accusations were seamy and deeply entangled with Trump’s political rise.

Trump was charged with fudging his business' records to veil a $130,000 payoff to porn actor Stormy Daniels. She was paid, late in Trump’s 2016 campaign, not to tell the public about a sexual encounter she maintains the two had a decade earlier. He says nothing sexual happened between them and that he did nothing wrong.

Prosecutors said Daniels was paid off — through Trump's personal attorney at the time, Michael Cohen — as part of a wider effort to keep voters from hearing about Trump's alleged extramarital escapades.

Trump denies the alleged encounters occurred. His lawyers said he wanted to squelch the stories to protect his family, not his campaign. And while prosecutors said Cohen's reimbursements for paying Daniels were deceptively logged as legal expenses, Trump says that's simply what they were.

“For this I got indicted,” Trump lamented to the judge Friday. “It’s incredible, actually."

Trump's lawyers tried unsuccessfully to forestall a trial, and later to get the conviction overturned, the case dismissed or at least the sentencing postponed.

Trump attorneys have leaned heavily into assertions of presidential immunity from prosecution, and they got a boost in July from a Supreme Court decision that affords former commanders-in-chief considerable immunity.

Trump was a private citizen and presidential candidate when Daniels was paid in 2016. He was president when the reimbursements to Cohen were made and recorded the following year.

Merchan, a Democrat, repeatedly postponed the sentencing, initially set for July. But last week, he set Friday's date, citing a need for “finality.”

Trump's lawyers then launched a flurry of last-minute efforts to block the sentencing. Their last hope vanished Thursday night with a 5-4 Supreme Court ruling that declined to delay the sentencing.

Meanwhile, the other criminal cases that once loomed over Trump have ended or stalled ahead of trial.

After Trump's election, special counsel Jack Smith closed out the federal prosecutions over Trump’s handling of classified documents and his efforts to overturn his 2020 election loss to Democrat Joe Biden. A state-level Georgia election interference case is locked in uncertainty after prosecutorFaniWillis was removed from it.

Associated Press writer Adriana Gomez Licon in West Palm Beach, Florida, contributed to this report.

Follow the AP's coverage of President-elect Donald Trump at https://apnews.com/hub/donald-trump.

President-elect Donald Trump appears on a video feed for his sentencing for for his hush money conviction in a Manhattan courtroom on Friday, Jan. 10, 2025 in New York. (Curtis Means/Pool Photo via AP)

Attorney Emil Bove, left, listens as attorney Todd Blanche and President-elect Donald Trump, seen on a television screen, appear virtually for sentencing for Trump's hush money conviction in a Manhattan courtroom on Friday, Jan. 10, 2025 in New York. (Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post via AP, Pool)

Attorney Todd Blanche and President-elect Donald Trump, seen on a television screen, appear virtually for sentencing for Trump's hush money conviction in a Manhattan courtroom on Friday, Jan. 10, 2025 in New York. (Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post via AP, Pool)

President-elect Donald Trump appears on a video feed for his sentencing for for his hush money conviction in a Manhattan courtroom on Friday, Jan. 10, 2025 in New York. (Curtis Means/Pool Photo via AP)

U.S. President-elect Donald Trump appears remotely for a sentencing hearing in front of New York State Judge Juan Merchan in the criminal case in which he was convicted in 2024 on charges involving hush money paid to a porn star, at New York Criminal Court in Manhattan in New York, Jan. 10, 2025. (Brendan McDermid via AP, Pool)

Demonstrators protest outside Manhattan criminal court before the start of the sentencing in President-elect Donald Trump's hush money case, Friday, Jan. 10, 2025, in New York. (AP Photo/Yuki Iwamura)

Demonstrators protest outside Manhattan criminal court before the start of the sentencing in President-elect Donald Trump's hush money case, Friday, Jan. 10, 2025, in New York. (AP Photo/Yuki Iwamura)

Demonstrators protest outside Manhattan criminal court before the start of the sentencing in President-elect Donald Trump's hush money case, Friday, Jan. 10, 2025, in New York. (AP Photo/Yuki Iwamura)

Demonstrators protest outside Manhattan criminal court before the start of the sentencing in President-elect Donald Trump's hush money case, Friday, Jan. 10, 2025, in New York. (AP Photo/Yuki Iwamura)

A man impersonating President-elect Donald Trump walks outside Manhattan criminal court before the start of the sentencing in Trump's hush money case, Friday, Jan. 10, 2025, in New York. (AP Photo/Yuki Iwamura)

A supporter for President-elect Donald Trump takes a photo of the Manhattan criminal courthouse before the start of the sentencing in Trump's hush money case, Friday, Jan. 10, 2025, in New York. (AP Photo/Yuki Iwamura)

A man crosses the street outside Manhattan criminal court before the start of the sentencing in President-elect Donald Trump's hush money case, Friday, Jan. 10, 2025, in New York. (AP Photo/Yuki Iwamura)

FILE - Judge Juan M. Merchan sits for a portrait in his chambers in New York, March 14, 2024. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig, File)

ATLANTA (AP) — A pregnant woman in Georgia was declared brain-dead after a medical emergency and doctors have kept her on life support for three months to allow enough time for the baby to be born and comply with Georgia’s strict anti-abortion law, family members say.

The case is the latest consequence of abortion bans introduced in some states since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade three years ago.

Adriana Smith, a 30-year-old mother and nurse, was declared brain-dead — meaning she is legally dead — in February, her mother, April Newkirk, told Atlanta TV station WXIA.

Newkirk said her daughter had intense headaches more than three months ago and went to Atlanta's Northside Hospital, where she received medication and was released. The next morning, her boyfriend woke to her gasping for air and called 911. Emory University Hospital determined she had blood clots in her brain and she was later declared brain-dead.

Newkirk said Smith is now 21 weeks pregnant. Removing breathing tubes and other life-saving devices would likely kill the fetus.

Northside did not respond to a request for comment Thursday. Emory Healthcare said it could not comment on an individual case because of privacy rules, but released a statement saying it “uses consensus from clinical experts, medical literature, and legal guidance to support our providers as they make individualized treatment recommendations in compliance with Georgia’s abortion laws and all other applicable laws. Our top priorities continue to be the safety and wellbeing of the patients we serve.”

Smith's family says Emory doctors have told them they are not allowed to stop or remove the devices that are keeping her breathing because state law bans abortion after cardiac activity can be detected — generally around six weeks into pregnancy.

The law was adopted in 2019 but not enforced until after Roe v. Wade was overturned in 2022, opening the door to state abortion bans. Georgia's ban includes an exception if an abortion is necessary to maintain the life of the woman.

Smith's family, including her five-year-old son, still visit her in the hospital.

Newkirk said doctors told the family that the fetus has fluid on the brain and that they're concerned about his health.

“She’s pregnant with my grandson. But he may be blind, may not be able to walk, may not survive once he’s born,” Newkirk said. She has not commented on whether the family wants Smith removed from life support.

Monica Simpson, executive director of SisterSong, the lead plaintiff in a lawsuit challenging Georgia’s abortion law, said the situation is problematic.

"Her family deserved the right to have decision-making power about her medical decisions,” Simpson said in a statement. “Instead, they have endured over 90 days of retraumatization, expensive medical costs, and the cruelty of being unable to resolve and move toward healing.”

Lois Shepherd, a bioethicist and law professor at the University of Virginia, said she does not believe Georgia's law requires life support in this case.

But she said whether a state could insist Smith remains on the breathing and other devices is uncertain since the 2022 ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, which overturned Roe including that fetuses do not have the rights of people.

“Pre-Dobbs, a fetus didn’t have any rights,” Shepherd said. “And the state’s interest in fetal life could not be so strong as to overcome other important rights, but now we don’t know.”

Brain death in pregnancy is rare. Even rarer still are cases in which doctors aim to prolong the pregnancy after a woman is declared brain-dead.

“It’s a very complex situation, obviously, not only ethically but also medically,” said Dr. Vincenzo Berghella, director of maternal fetal medicine at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

A 2021 review that Berghella co-authored scoured medical literature going back decades for cases in which doctors declared a woman brain-dead and aimed to prolong her pregnancy. It found 35.

Of those, 27 resulted in a live birth, the majority either immediately declared healthy or with normal follow-up tests. But Berghella also cautioned that the Georgia case was much more difficult because the pregnancy was less far along when the woman was declared brain dead. In the 35 cases he studied, doctors were able to prolong the pregnancy by an average of just seven weeks before complications forced them to intervene.

“It’ s just hard to keep the mother out of infection, out of cardiac failure,” he said.

Berghella also found a case from Germany that resulted in a live birth when the woman was declared brain dead at nine weeks of pregnancy.

Georgia's law confers personhood on a fetus. Those who favor personhood say fertilized eggs, embryos and fetuses should be considered people with the same rights as those already born.

Georgia state Sen. Ed Setzler, a Republican who sponsored the 2019 law, said he supported Emory’s interpretation.

“I think it is completely appropriate that the hospital do what they can to save the life of the child,” Setzler said. “I think this is an unusual circumstance, but I think it highlights the value of innocent human life. I think the hospital is acting appropriately.”

Setzler said he believes it is sometimes acceptable to remove life support from someone who is brain dead, but that the law is “an appropriate check” because the mother is pregnant. He said Smith's relatives have “good choices,” including keeping the child or offering it for adoption.

Georgia’s abortion ban has been in the spotlight before.

Last year, ProPublica reported that two Georgia women died after they did not get proper medical treatment for complications from taking abortion pills. The stories of Amber Thurman and Candi Miller entered into the presidential race, with Democrat Kamala Harris saying the deaths were the result of the abortion bans that went into effect in Georgia and elsewhere after Dobbs.

The situation echoes a case in Texas more than a decade ago when a brain-dead woman was kept on maintenance measures for about two months because she was pregnant. A judge eventually ruled that the hospital keeping her alive against her family’s wishes was misapplying state law, and life support was removed.

Twelve states are enforcing abortion bans at all stages of pregnancy, with limited exceptions. Georgia is one of four with a ban that kicks in at or around six weeks into pregnancy — often before women realize they’re pregnant.

Last year, the Texas Supreme Court ruled unanimously against a group of women who challenged that state’s abortion ban, saying the exceptions were being interpreted so narrowly that they were denied abortion access as they dealt with serious pregnancy complications. This year, the state Senate has passed a bill that seeks to clarify when abortions are allowed.

South Dakota produced a video to inform doctors about when exceptions should apply. Abortion rights groups have blasted it.

The U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments in December over whether the federal law that requires hospitals to provide abortion in emergency medical situations should apply. A ruling is expected in coming months.

Mulvihill reported from Cherry Hill, New Jersey. Associated Press journalists Kate Brumback, Sudhin Thanawala, Sharon Johnson and Charlotte Kramon contributed.

Emory University Hospital Midtown is seen on Thursday, May 15, 2025, in Atlanta. (AP Photo/Brynn Anderson)

Emory University Hospital Midtown is seen on Thursday, May 15, 2025, in Atlanta. (AP Photo/Brynn Anderson)

Emory University Hospital Midtown is seen on Thursday, May 15, 2025, in Atlanta. (AP Photo/Brynn Anderson)

Emory University Hospital Midtown is seen on Thursday, May 15, 2025, in Atlanta. (AP Photo/Brynn Anderson)

FILE - The Georgia State Capitol is seen from Liberty Plaza in downtown Atlanta, April 6, 2020. (Alyssa Pointer/Atlanta Journal-Constitution via AP, File)