BOULDER, Colo. (AP) — Bill McCartney, who coached Colorado to its only football national championship in 1990, has died. He was 84.

The charismatic figure known as Coach Mac died Friday night “after a courageous journey with dementia,” according to a family statement. His family announced in 2016 that he had been diagnosed with dementia and Alzheimer's.

“Coach Mac touched countless lives with his unwavering faith, boundless compassion, and enduring legacy as a leader, mentor and advocate for family, community and faith,” the family said in its statement. “As a trailblazer and visionary, his impact was felt both on and off the field, and his spirit will forever remain in the hearts of those he inspired.”

McCartney remains the winningest coach in Colorado history, with a record of 93-55-5. He was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 2013.

“I am very saddened at the passing of Coach Mac,” said Colorado athletic director Rick George, who remained lifelong friends with McCartney after he hired George as his recruiting coordinator in 1987. “Coach Mac was an incredible man who taught me about the importance of faith, family and being a good husband, father and grandfather. He instilled discipline and accountability to all of us who worked and played under his leadership."

McCartney led Colorado to its best season in 1990, when the team finished 11-1-1 and beat Notre Dame in the Orange Bowl to clinch the national title. That season included a win at Missouri where the Buffaloes scored the winning touchdown on a “fifth down” as time expired — one of the biggest blunders in college football history.

The chain crew didn’t flip the marker from second to third down and the officials failed to notice. On fourth down — fifth in actuality — Charles Johnson scored to keep Colorado’s national title hopes afloat. Asked later if he would consider forfeiting the game, McCartney pointed to poor field conditions and didn’t think it was a fair test.

McCartney coached at Colorado from 1982-94, retiring early to spend more time with his wife, Lyndi, who died in 2013. Following his retirement, he worked full time at Promise Keepers, a ministry he started in 1990 after converting from Catholicism and whose aim is to encourage “godly men.”

The organization became a flash point in state politics, advocating unsuccessfully that gays be denied the designation of “protected class,” a position by the group that drew campus protests. He left as Promise Keepers’ president in 2003 because of his wife’s health but returned five years later.

As a football coach, McCartney’s impact at Colorado was immense. During a six-year span in the late ’80s and early ’90s, his teams were right up there with the powers of the time. McCartney coached Colorado to three Big Eight titles, 10 consecutive winning seasons in league competition and a 58-29-4 mark in conference play, all still school bests.

His 1989 squad went 11-1 and lost to Notre Dame 21-6 in the Orange Bowl. That set the groundwork for a national championship team that featured quarterbacks Darian Hagan and Charles Johnson, tailback Eric Bieniemy, and a stalwart defense that included Alfred Williams, Greg Biekert, Chad Brown and Kanavis McGhee.

“A hall of fame coach but somehow a better man and human being,” Brown wrote in a post on X, formerly known as Twitter. “Love you Coach!”

Added Williams in a post on X: “His legacy is firmly built on love, character, integrity, hope, and faith. I will always thank God for blessing me with the opportunity to have him in my life. Thank you Coach for loving on all of us.”

To think, McCartney nearly chose a basketball coaching career.

Born in Riverview, Michigan, McCartney played center and linebacker at the University of Missouri, where he met his wife. He later coached basketball and football at a high school in Dearborn, Michigan. His teams were good, too, each capturing the state title in 1973.

He caught the eye of Michigan football coach Bo Schembechler, who wanted McCartney to join his staff at Michigan. If that weren’t enough, Michigan basketball coach Johnny Orr urged him to join his staff.

McCartney couldn’t decide. His wife gave him some simple advice — follow his heart.

He stepped into the world of college football.

McCartney learned under Schembechler for eight seasons, until an opportunity came up to guide his own team. When the late Chuck Fairbanks left Colorado to become involved with the New Jersey Generals in the upstart United States Football League, McCartney asked Schembechler if the Hall of Fame coach would put in a good word for him.

Schembechler’s backing carried a lot of weight, and then-Colorado athletic director Eddie Crowder gave McCartney the position.

It was a rough start for McCartney with only seven victories in his first three seasons, including a 1-10 finish in 1984. Then things started to turn.

His last season with the Buffaloes was 1994, when the team went 11-1 behind a roster that included Kordell Stewart, Michael Westbrook and the late Rashaan Salaam. That season featured the “Miracle in Michigan,” with Westbrook hauling in a 64-yard TD catch from Stewart on a Hail Mary as time expired in a road win over the Wolverines. Salaam also rushed for 2,055 yards and won the Heisman Trophy.

McCartney also groomed the next wave of coaches, mentoring assistants such as Gary Barnett, Jim Caldwell, Ron Dickerson, Gerry DiNardo, Karl Dorrell, Jon Embree, Les Miles, Rick Neuheisel, Bob Simmons, Lou Tepper, Ron Vanderlinden and John Wristen.

In recent years, McCartney got to watch grandson Derek play defensive line at Colorado. Derek’s father, Shannon Clavelle, was a defensive lineman for Colorado from 1992-94 before playing a few seasons in the NFL. Derek’s brother, T.C. McCartney, was a quarterback at LSU and is the son of late Colorado quarterback Sal Aunese, who played for Bill McCartney in 1987 and ’88 before being diagnosed with stomach cancer in 1989 and dying six months later at 21.

Growing up, Derek McCartney used to go next door to his grandfather’s house to listen to his stories. He never tired of them.

Derek soaked up the tales about Salaam winning the Heisman Trophy and how Colorado beat Notre Dame in the Orange Bowl to cement the national title. His grandfather had a picture of the famous play at Michigan and a button to push to hear the broadcast audio.

When playing for Colorado, hardly a day would go by when someone didn't ask Derek if he was somehow related to the coach.

“I like when that happens,” Derek said.

Get poll alerts and updates on the AP Top 25 throughout the season. Sign up here. AP college football: https://apnews.com/hub/ap-top-25-college-football-poll and https://apnews.com/hub/college-football

FILE - Colorado University head coach Bill McCartney repositions tight end Jon Embree (80) during practice in Irvine, Calif., Dec. 26, 1985. (AP Photo/Doug Pizac, File)

FILE - Colorado coach Bill McCartney, left, is escorted off the Orange Bowl field after the Buffaloes defeated Notre Dame, 10-9, in the 57th annual Orange Bowl Classic in Miami, Jan. 1, 1991. (AP Photo/Ray Fairall, File)

FILE - Retired Colorado head football coach Bill McCartney watches in the second half of an NCAA college basketball game, March 9, 2019, in Boulder, Colo. (AP Photo/David Zalubowski, File)

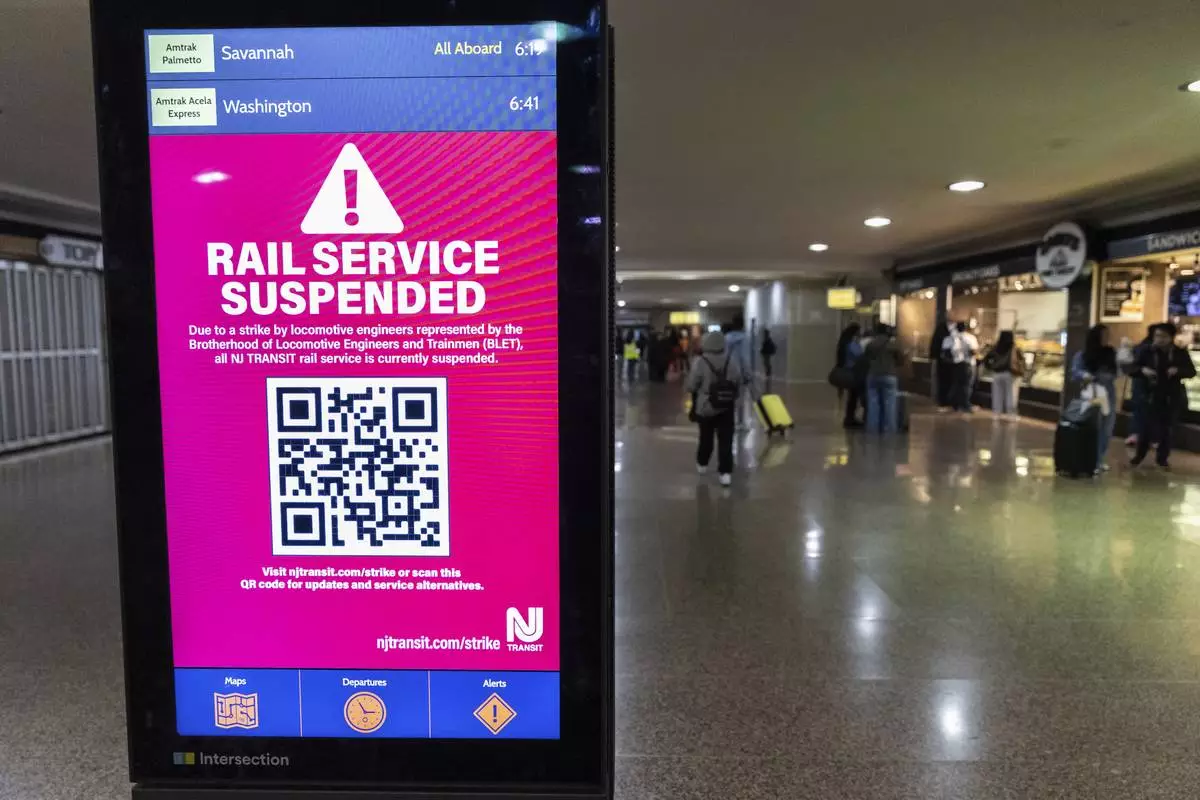

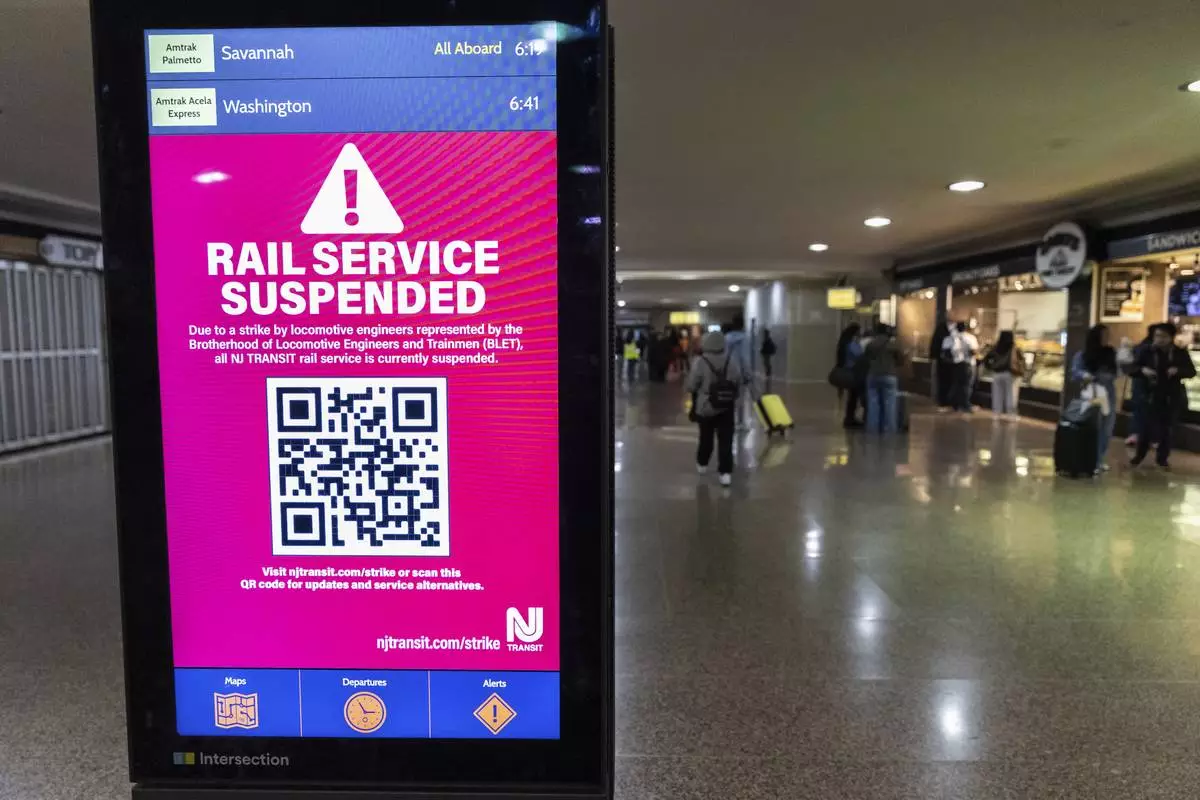

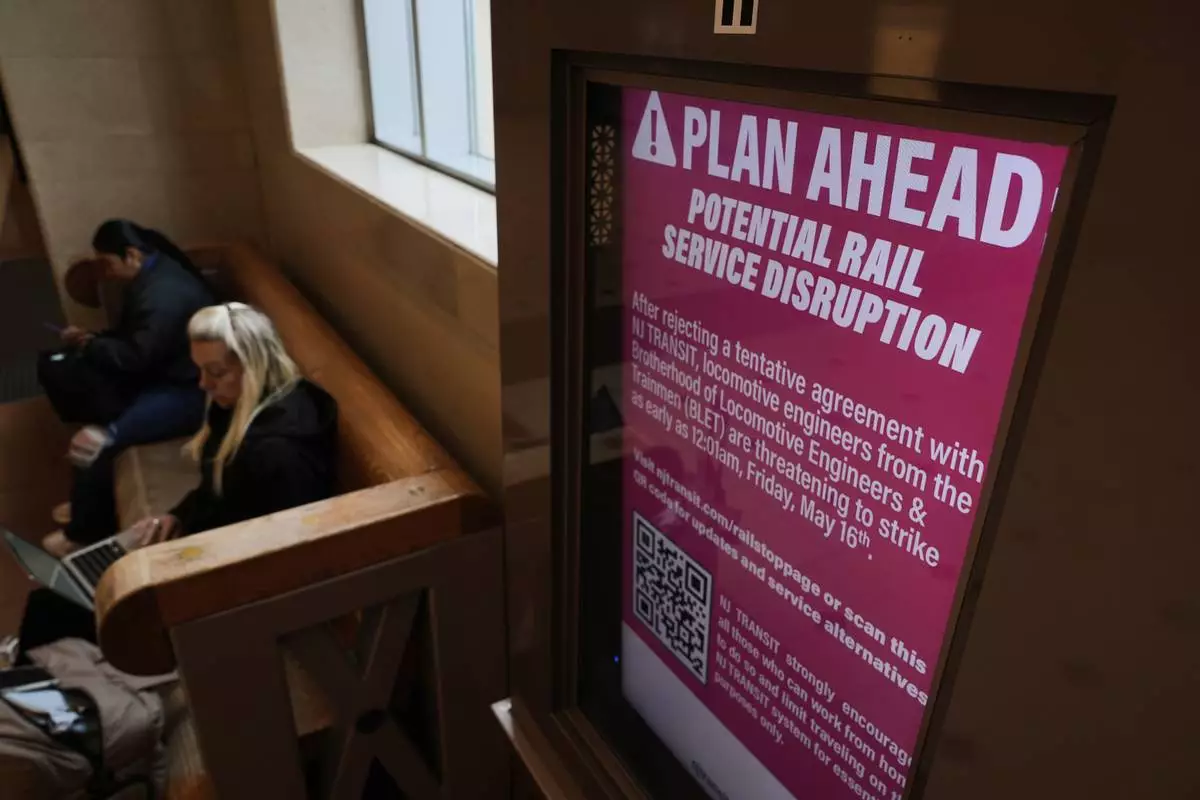

New Jersey Transit train engineers went on strike, leaving train terminals quiet for Friday's rush hour and an estimated 350,000 commuters in New Jersey and New York City to seek other means to reach their destinations or consider staying home.

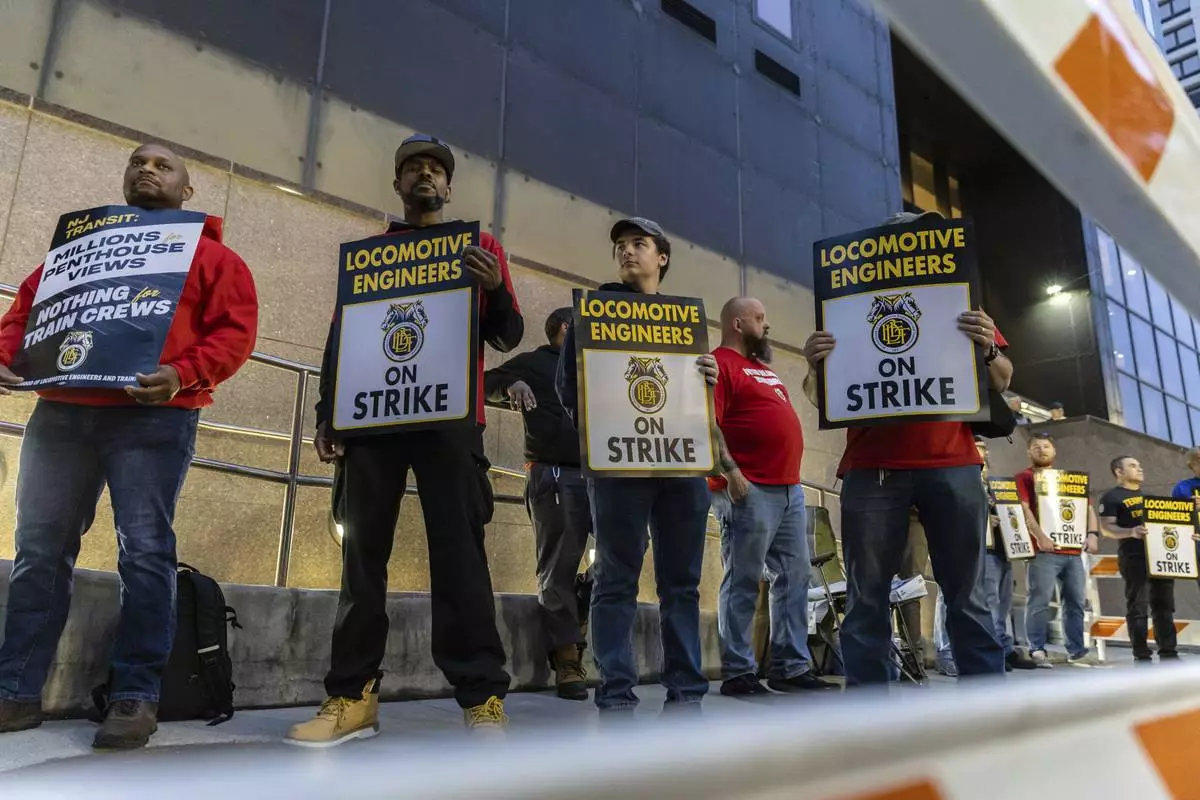

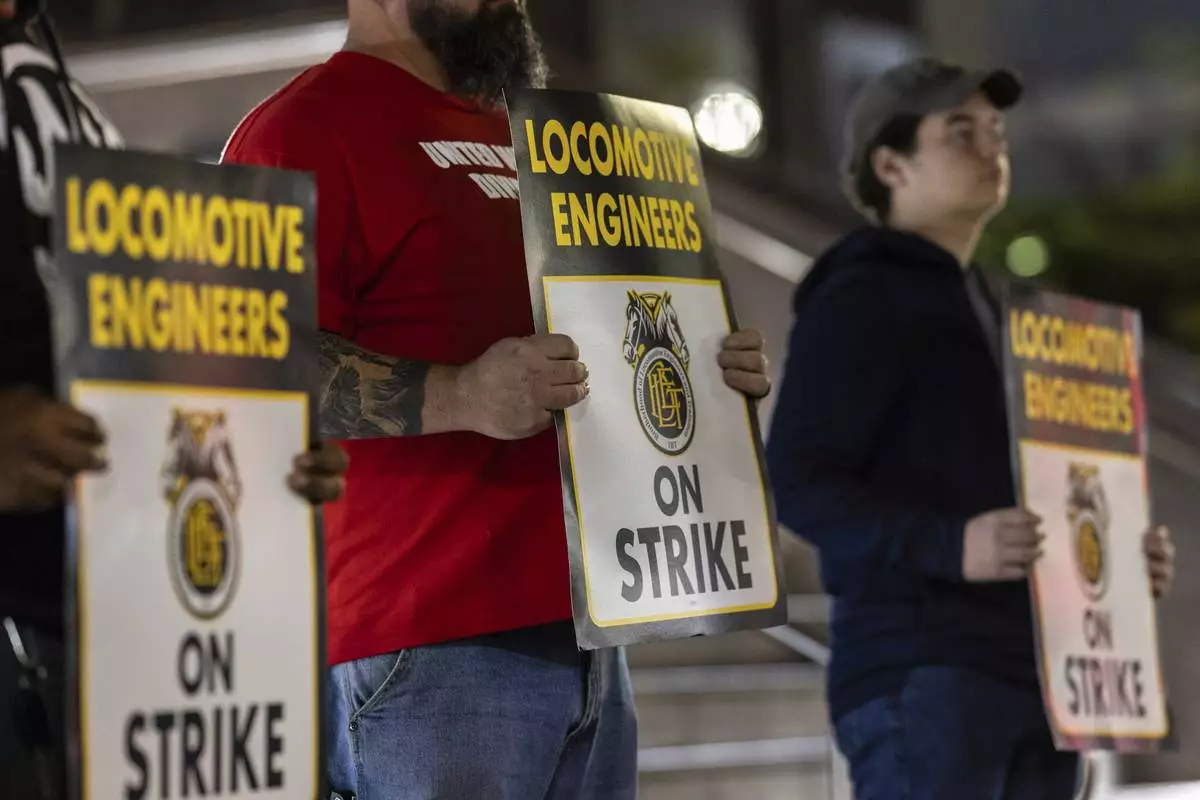

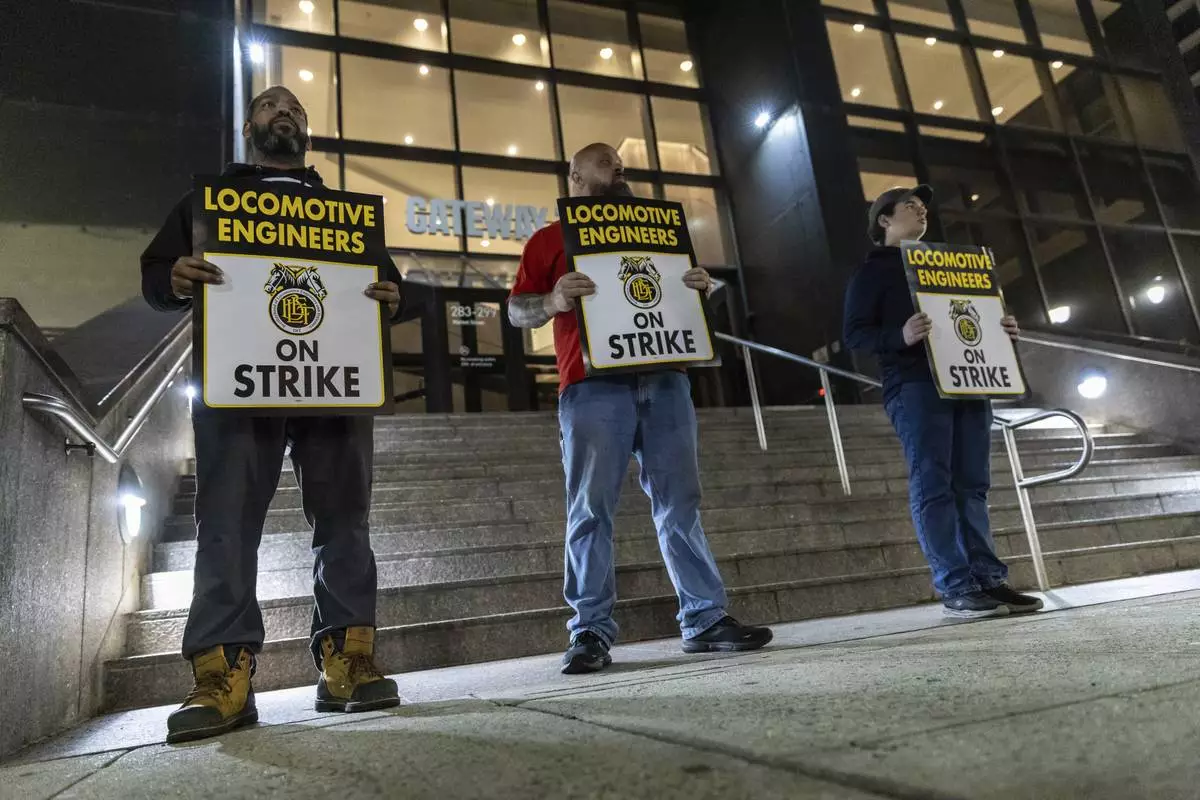

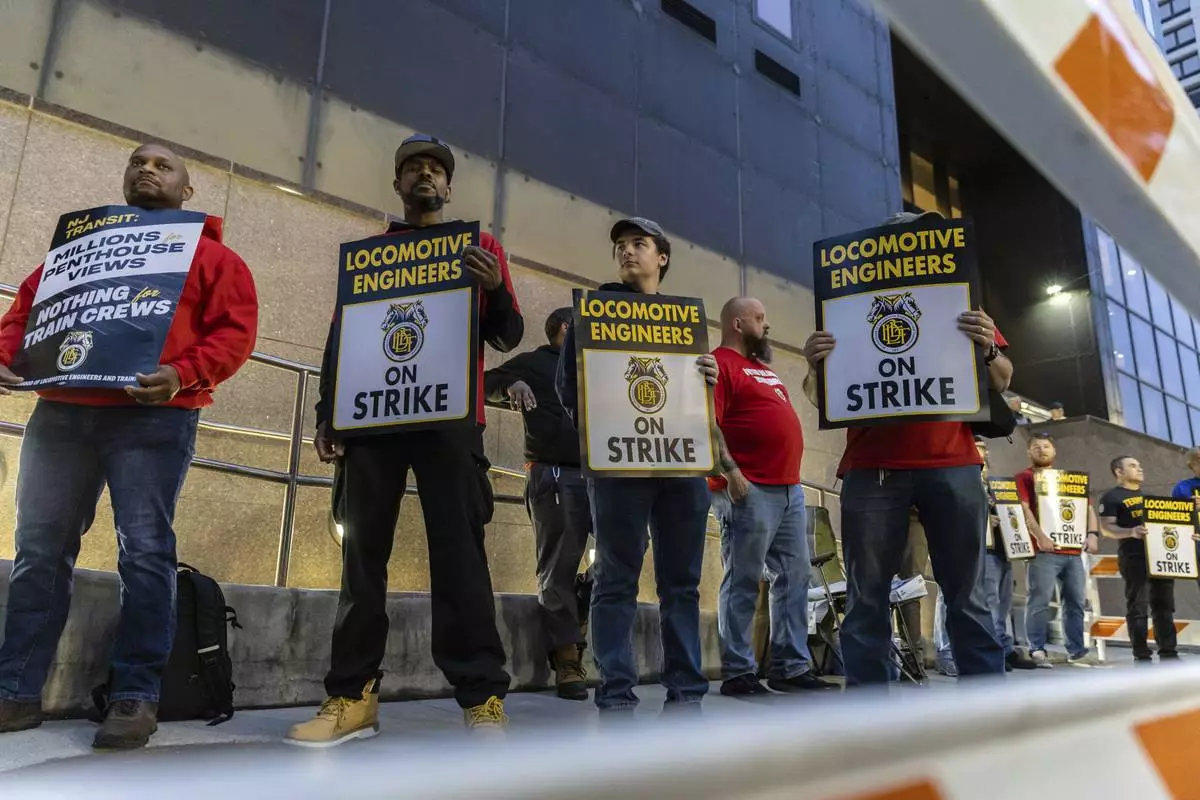

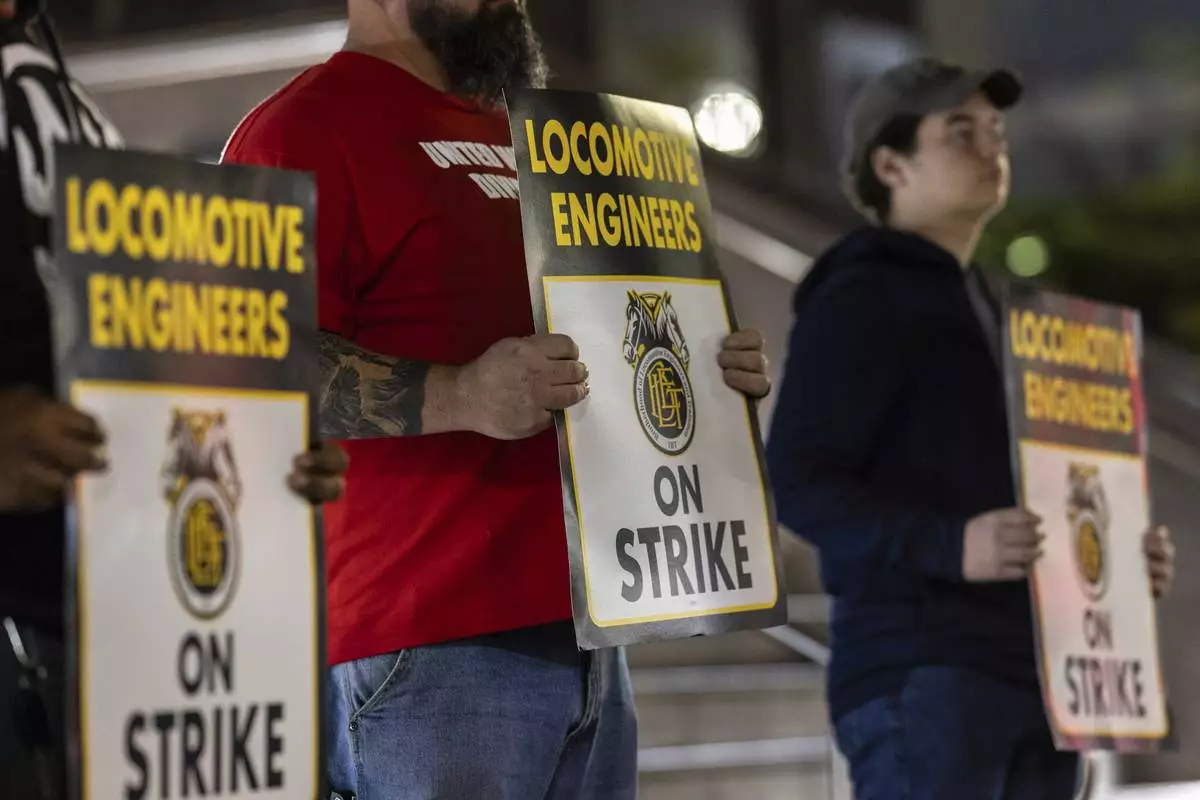

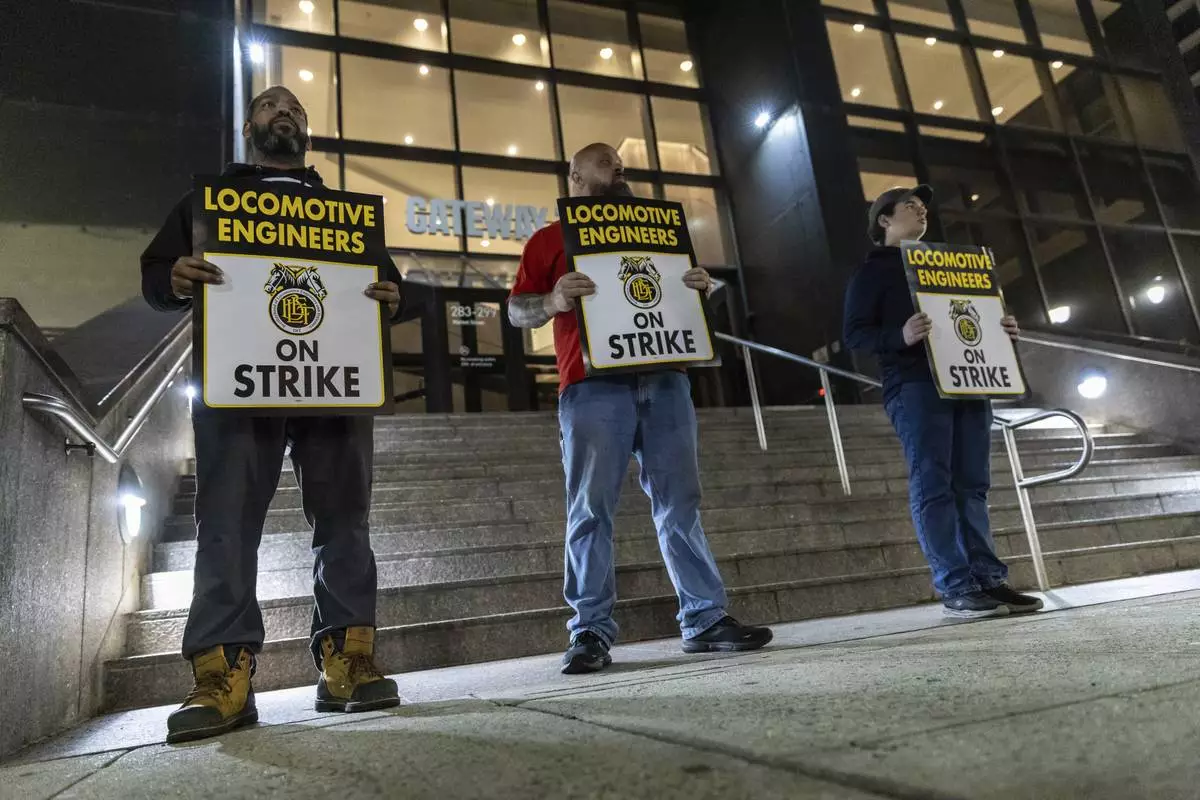

Groups of picketers gathered in front of transit headquarters in Newark and at the Hoboken Terminal, carrying signs that said “Locomotive Engineers on Strike” and “NJ Transit: Millions for Penthouse Views Nothing for Train Crews.”

Friday’s rail commute into New York from New Jersey is typically the lightest of the week. In New York, some commuters from New Jersey said they could not work remotely and had to come in, taking busses to the Port Authority bus terminal in Manhattan.

David Milosevich, a fashion and advertising casting director, was on his way to a photo shoot in Brooklyn. At 1 a.m. he checked his phone and saw the strike was on.

“I left home very early because of it,” he said, grabbing the bus in Montclair, New Jersey, and arriving in Manhattan at 7 a.m. “I think a lot of people don’t come in on Fridays since COVID. I don’t know what’s going to happen Monday.”

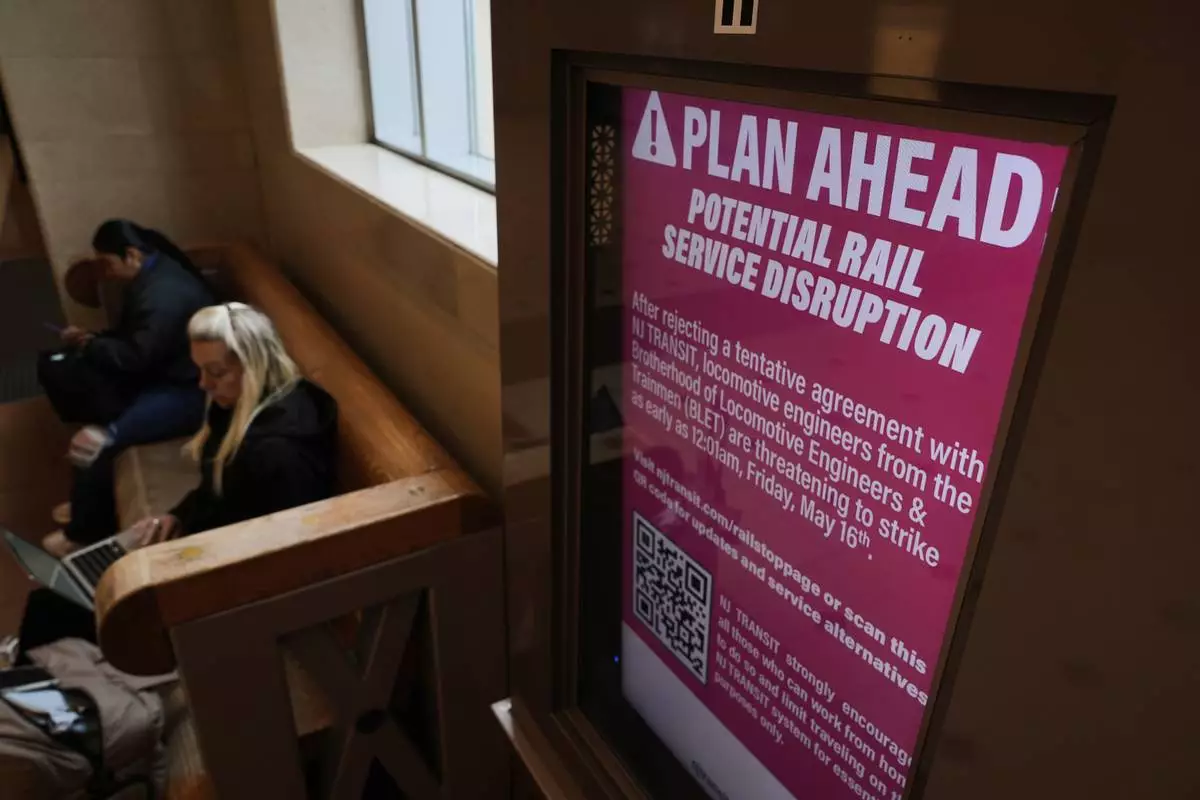

The walkout comes after the latest round of negotiations on Thursday didn’t produce an agreement. It is the state’s first transit strike in more than 40 years and comes a month after union members overwhelmingly rejected a labor agreement with management.

“We presented them the last proposal; they rejected it and walked away with two hours left on the clock," said Tom Haas, general chairman of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen.

NJ Transit CEO Kris Kolluri described the situation as a “pause in the conversations.”

“I certainly expect to pick back up these conversations as soon as possible,” he said late Thursday during a joint news conference with New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy. “If they’re willing to meet tonight, I’ll meet them again tonight. If they want to meet tomorrow morning, I’ll do it again. Because I think this is an imminently workable problem. The question is, do they have the willingness to come to a solution.”

Murphy and Kolluri planned a Friday morning news conference.

A few blocks from the Port Authority bus terminal, the NJ Transit train terminal was quiet, with an NJ transit worker in an orange hoody on hand to warn riders it was closed, Signs read: “service suspended.”

The South Amboy train station, an express stop on the NJ Transit rail line, was vacant. But the Waterway ferry that began service only 18 months ago from a waterside launching point that’s a 10-minute walk from the train station was busier than usual for its 6:40 a.m., 55-minute nonstop trip to Manhattan.

The ferry runs once an hour during the morning and evening commutes. With about three dozen people aboard, more than half the seats in the ferry’s lower deck were empty.

Murphy said it was important to “reach a final deal that is both fair to employees and at the same time affordable to New Jersey’s commuters and taxpayers.”

"Again, we cannot ignore the agency’s fiscal realities,” Murphy said.

The announcement came after 15 hours of nonstop contract talks, according to the union.

NJ Transit — the nation’s third-largest transit system — operates buses and rail in the state, providing nearly 1 million weekday trips, including into New York City. The walkout halts all NJ Transit commuter trains, which provide heavily used public transit routes between New York City’s Penn Station on one side of the Hudson River and communities in northern New Jersey on the other, as well as the Newark airport, which has grappled with unrelated delays of its own recently.

The agency had announced contingency plans in recent days, saying it planned to increase bus service, but warned riders that the buses would only add “very limited” capacity to existing New York commuter bus routes in close proximity to rail stations and would not start running until Monday.

However, the agency noted that the buses would not be able to handle close to the same number of passengers — only about 20% of current rail customers — so it urged people who could work from home to do so.

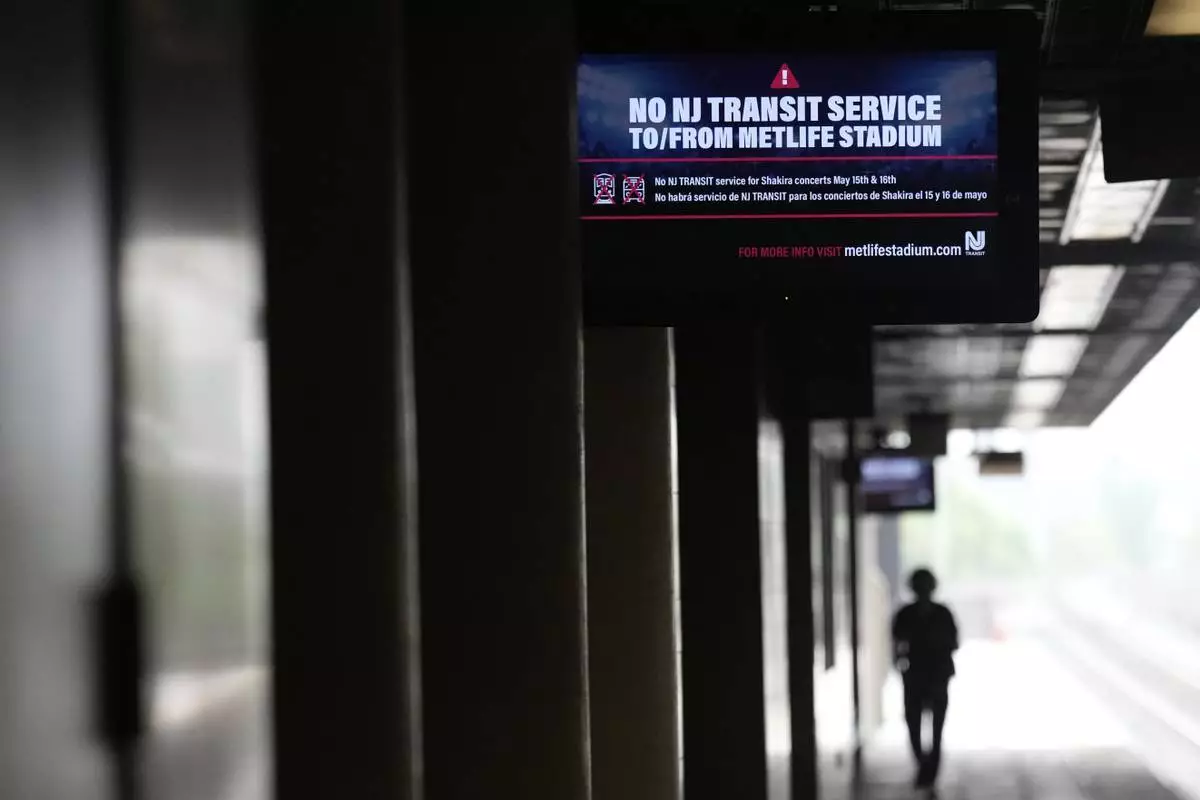

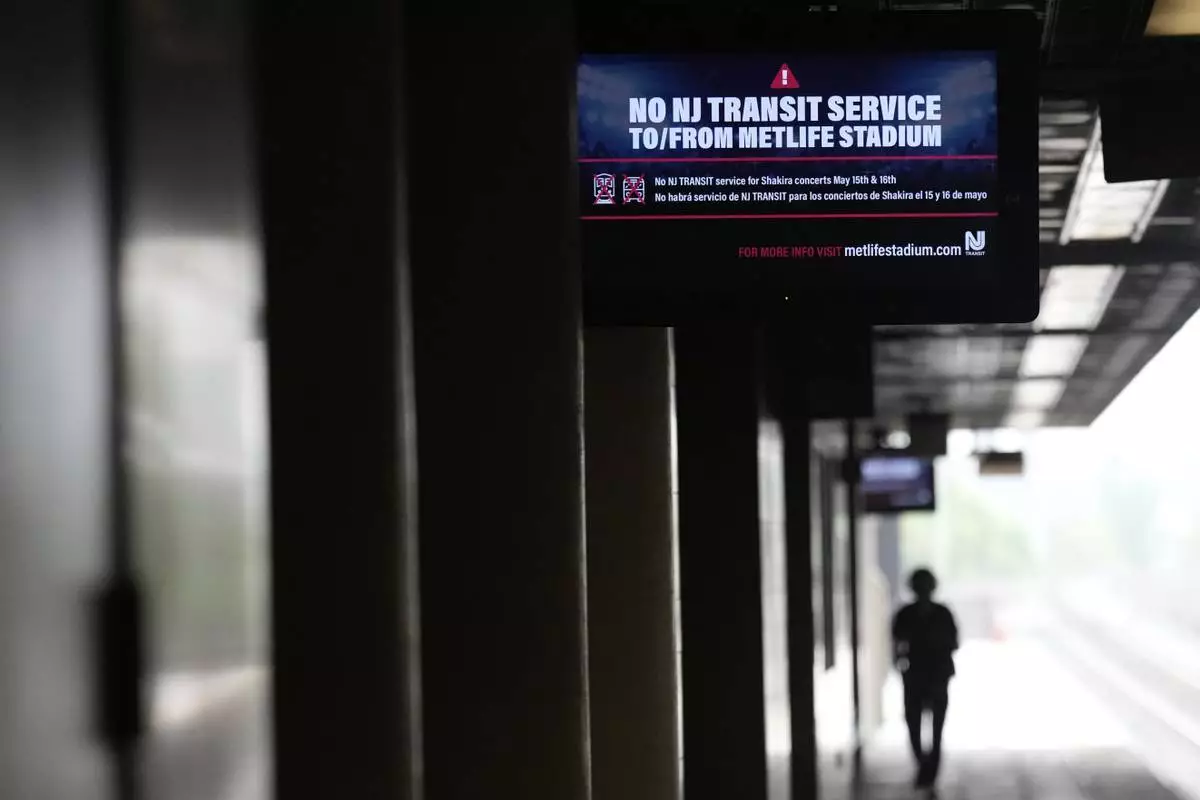

Earlier, even the thread of a strike caused travel disruptions. Amid the uncertainty, the transit agency canceled train and bus service for Shakira concerts Thursday and Friday at MetLife Stadium in New Jersey.

The parties met Monday with a federal mediation board in Washington to discuss the matter, and a mediator was present during Thursday’s talks. Kolluri said Thursday night that the mediation board has suggested a Sunday morning meeting to resume talks.

Wages have been the main sticking point of the negotiations between the agency and the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen that wants to see its members earn wages comparable to other passenger railroads in the area. The union says its members earn an average salary of $113,000 a year and says an agreement could be reached if agency CEO Kris Kolluri agrees to an average yearly salary of $170,000.

NJ Transit leadership, though, disputes the union’s data, saying the engineers have average total earnings of $135,000 annually, with the highest earners exceeding $200,000.

Kolluri and Murphy said Thursday night that the problem isn’t so much whether both sides can agree to a wage increase, but whether they can do so under terms that wouldn’t then trigger other unions to demand similar increases and create a financially unfeasible situation for NJ Transit.

Congress has the power to intervene and block the strike and force the union to accept a deal, but lawmakers have not shown a willingness to do that this time like they did in 2022 to prevent a national freight railroad strike.

The union has seen steady attrition in its ranks at NJ Transit as more of its members leave to take better-paying jobs at other railroads. The number of NJ Transit engineers has shrunk from 500 several months ago to about 450.

Associated Press reporters Cedar Attanasio and Larry Neumeister in New York, Hallie Golden in Seattle and Josh Funk in Omaha, Nebraska, contributed to this report.

An information screen informing commuters of the rail service suspension, due to the strike by Union members from the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen, inside Newark Penn Station on Friday, May 16, 2025 in Newark, New Jersey. (AP Photo/Stefan Jeremiah)

An information screen informing commuters of the rail service suspension, due to the strike by Union members from the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen, inside Newark Penn Station on Friday, May 16, 2025 in Newark, New Jersey. (AP Photo/Stefan Jeremiah)

An empty PATH train platform with an information screen informing commuters of the rail service suspension, due to the strike by Union members from the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen, inside Newark Penn Station on Friday, May 16, 2025 in Newark, New Jersey. (AP Photo/Stefan Jeremiah)

Union members from the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen form a picket line outside the NJ Transit Headquarters on Friday, May 16, 2025 in Newark, New Jersey. (AP Photo/Stefan Jeremiah)

An electronic display advises commuters of NJ Transit service disruptions at the Secaucus Junction station in Secaucus, N.J., Wednesday, May 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

An NJ Transit train pulls into the Secaucus Junction station in Secaucus, N.J., Wednesday, May 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

An electronic display advises commuters of potential NJ Transit service disruptions at the Secaucus Junction station in Secaucus, N.J., Wednesday, May 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

Union members from the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen form a picket line outside the NJ Transit Headquarters on Friday, May 16, 2025 in Newark, New Jersey. (AP Photo/Stefan Jeremiah)

Union members from the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen form a picket line outside the NJ Transit Headquarters on Friday, May 16, 2025 in Newark, New Jersey. (AP Photo/Stefan Jeremiah)