ST. AUGUSTINE, Fla. (AP) — Lori Matthias and her husband had tired of Atlanta traffic when they moved to St. Augustine, Florida, in 2023. For Mike Waldron and his wife, moving from the Boston area in 2020 to a place that bills itself as “the nation's oldest city” was motivated by a desire to be closer to their adult children.

They were among thousands of white-collar, remote workers who migrated to the St. Augustine area in recent years, transforming the touristy beach town into one of the top remote work hubs in the United States.

Click to Gallery

Aliyah Meyer, an official with the St. Johns County Chamber of Commerce, walks through a downtown neighborhood in St. Augustine, Fla., which has become a top remote work hub in the U.S. during the 2020s, on Thursday, March 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Mike Schneider.)

An oversized alligator model sits on top of a truck's trailer at the St. Augustine Alligator Farm Zoological Park, a top tourist attraction in St. Augustine, Fla. on Thursday, March 13, 2025.

Walkers make their way through the downtown historic district in St. Augustine, Fla., which has become a top remote work hub in the U.S. during the 2020s, on Thursday, March 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Mike Schneider.)

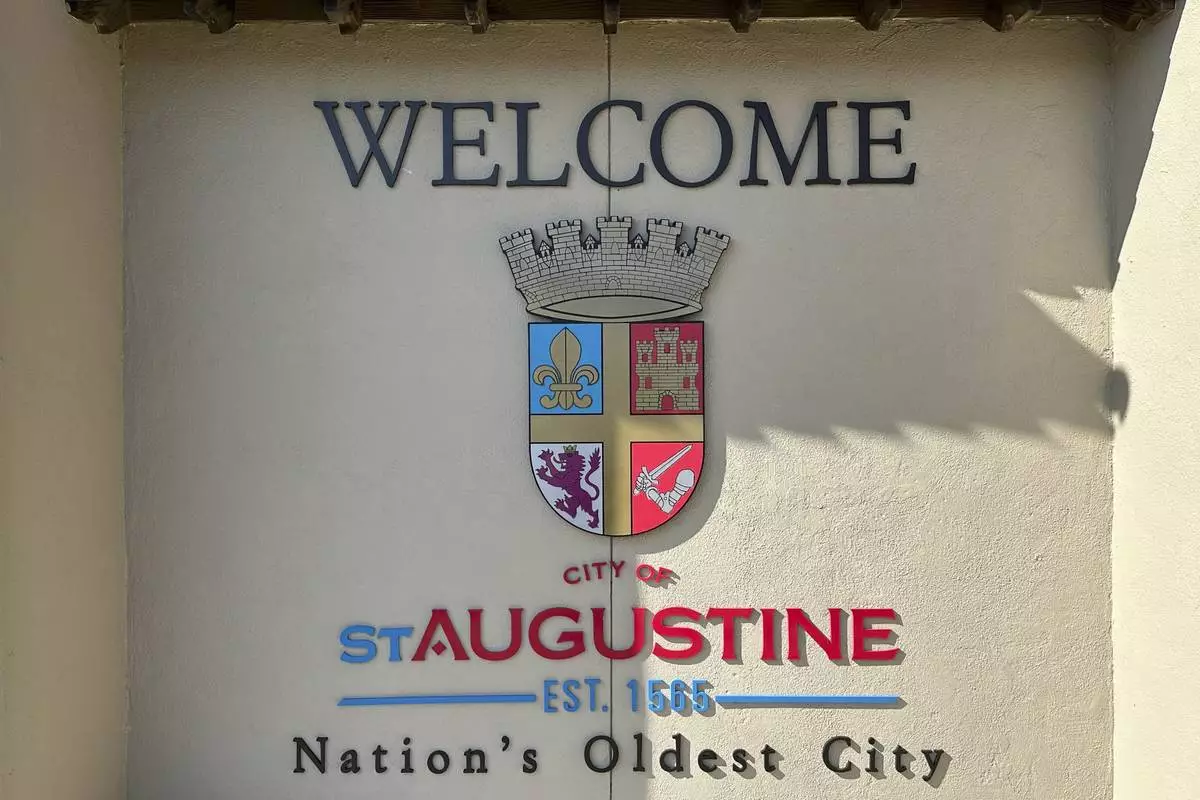

A welcome sign greets visitors to St. Augustine, Fla., which has become a top remote work hub in the U.S. during the 2020s, on Thursday, March 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Mike Schneider.)

Health care sales executive Mike Waldron works out of his home office in St. Augustine, Fla., which has become a top remote work hub in the U.S. during the 2020s, on Thursday, March 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Mike Schneider.)

Health sales care executive Mike Waldron looks at a cumquat tree in the sunroom at his home in St. Augustine, Fla., which has become a top remote work hub in the U.S. during the 2020s, on Thursday, March 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Mike Schneider.)

Matthias fell in love with St. Augustine’s small town feeling, trading the hour-long commute she had in Atlanta for bumping into friends and acquaintances while running errands.

“The whole pace here is slower and I’m attracted to that,” said Matthias, who does sales and marketing for a power tool company. “My commute is like 30 steps from my kitchen to my office. It’s just different. It’s just relaxed and friendly.”

Centuries before becoming a remote work hub, the St. Augustine area was claimed by the Spanish crown in the early 16th century after explorer Juan Ponce de Leon’s arrival. In modern times, it is best known for its Spanish architecture of terra cotta roofs and arched doorways, tourist-carrying trollies, a historic fort, an alligator farm, lighthouses and a shipwreck museum.

In St. Johns County, home to St. Augustine, the percentage of workers who did their jobs from home nearly tripled from 8.6% in 2018 to almost 24% in 2023, moving the northeast Florida county into the top ranks of U.S. counties with the largest share of people working remotely, according to U.S. Census Bureau figures.

Only counties with a heavy presence of tech, finance and government workers in metro Washington, Atlanta, Austin, Charlotte and Dallas, as well as two counties in North Carolina’s Research Triangle, had a larger share of their workforce working from home. But these were counties much more populous than the 335,000 residents in St. Johns County, which has grown by more than a fifth during this decade.

Scott Maynard, a vice president of economic development for the county’s chamber of commerce, attributes the initial influx of new residents to Florida’s lifting of COVID-19 restrictions in businesses and schools in the fall of 2020 while much of the country remained locked down.

“A lot of people were relocating here from the Northeast, the Midwest and California so that their children could get back to a face-to-face education,” Maynard said. “That brought in a tremendous number of people who had the ability to work remotely and wanted their children back in a face-to-face school situation.”

Public schools in St. Johns County are among the best in Florida, according to an annual report card by the state Department of Education.

The influx of new residents has brought growing pains, particularly when it comes to affordable housing since many of the new, remote workers moving into the area are wealthier than locals and able to outbid them on homes, officials said.

Many essential workers such as police officers, firefighters and teachers have been forced to commute from outside St. Johns County because of rising housing costs. The median home price grew from $405,000 in 2019 to almost $535,000 in 2023, according to Census Bureau figures, making the purchase of a home further out of reach for the county's essential workers.

Essential workers would need to earn at least $180,000 annually to afford the median price of a home in St. Johns County, but a teacher has an average salary of around $48,000 and a law enforcement officer earns around $58,000 on average, according to an analysis by the local chamber of commerce.

“What happened was a lot of the people, especially coming in from up North, were able to sell their homes for such a high value and come here and just pay cash since this seemed affordable to them,” said Aliyah Meyer, an economic researcher at the chamber of commerce. “So it kind of inflated the market and put a bit of a constraint on the local residents.”

Waldron, a sales executive in the health care industry, was able to sell his Boston home at the height of the pandemic and purchase a three-bedroom, two-bath home in a gated community by a golf course outside St. Augustine where “things really worked out to be less expensive down here."

The flexibility offered by fast wireless internet and the popularity of online meeting platforms since the start of the pandemic also helped.

“If I was still locked in an office, I would not have been able to move down here,” Waldron said.

Follow Mike Schneider on the social platform Bluesky: @mikeysid.bsky.social

Aliyah Meyer, an official with the St. Johns County Chamber of Commerce, walks through a downtown neighborhood in St. Augustine, Fla., which has become a top remote work hub in the U.S. during the 2020s, on Thursday, March 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Mike Schneider.)

An oversized alligator model sits on top of a truck's trailer at the St. Augustine Alligator Farm Zoological Park, a top tourist attraction in St. Augustine, Fla. on Thursday, March 13, 2025.

Walkers make their way through the downtown historic district in St. Augustine, Fla., which has become a top remote work hub in the U.S. during the 2020s, on Thursday, March 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Mike Schneider.)

A welcome sign greets visitors to St. Augustine, Fla., which has become a top remote work hub in the U.S. during the 2020s, on Thursday, March 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Mike Schneider.)

Health care sales executive Mike Waldron works out of his home office in St. Augustine, Fla., which has become a top remote work hub in the U.S. during the 2020s, on Thursday, March 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Mike Schneider.)

Health sales care executive Mike Waldron looks at a cumquat tree in the sunroom at his home in St. Augustine, Fla., which has become a top remote work hub in the U.S. during the 2020s, on Thursday, March 13, 2025. (AP Photo/Mike Schneider.)

WASHINGTON (AP) — The revelation that President Donald Trump's most senior national security officials posted the specifics of a military attack to a chat group that included a journalist hours before the attack took place in Yemen has raised many questions.

Among them is whether federal laws were violated, whether classified information was exposed on the commercial messaging app, and whether anyone will face consequences for the leaks.

Here's what we know so far, and what we don't know.

KNOWN: Signal is a publicly available app that provides encrypted communications, but it can be hacked. It is not approved for carrying classified information. On March 14, one day before the strikes, the Defense Department cautioned personnel about the vulnerability of Signal, specifically that Russia was attempting to hack the app, according to a U.S. official, who was not authorized to speak to the press and spoke on the condition of anonymity.

One known vulnerability is that a malicious actor, if they have access to a person's phone, can link their own device to the user's Signal — and essentially monitor messages remotely in real time.

NOT KNOWN: How frequently the administration and the Defense Department use Signal for sensitive government communications, and whether those on the chat were using unauthorized personal devices to transmit or receive those messages. The department put out an instruction in 2023 restricting what information could be posted on unauthorized and unclassified systems.

At a Senate Intelligence Committee hearing on Tuesday, Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard would not say whether she was accessing the information on her personal phone or government-issued phone, citing an ongoing investigation by the National Security Council.

KNOWN: The government has a requirement under the Presidential Records Act to archive all of those planning discussions.

NOT KNOWN: Whether anyone in the group archived the messages as required by law to a government server.

KNOWN: The chat group included 18 members, including Jeffrey Goldberg, editor-in-chief of The Atlantic. The group, called “Houthi PC Small Group,” likely for Houthi “principals committee” — was comprised of Trump’s senior-most advisers on national security, including Gabbard, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, Secretary of State Marco Rubio and CIA Director John Ratcliffe. The National Security Council said the text chain “appears to be authentic.”

NOT KNOWN: How Goldberg got added. Each agency principal named a staff member to be added to the chat, and Waltz named his staffer Alex Wong, as taking the lead in assembling the team that would monitor the attacks. It was not clear if Waltz himself, or a staffer managing Waltz's Signal account, sent Goldberg the invitation.

KNOWN: Just hours before the attack on the Houthis in Yemen began, Hegseth shared details on the timing, targets, weapons and sequence of strikes that would take place.

NOT KNOWN: The classification level of this information. In the Senate hearing, both Gabbard and Ratcliffe referred questions to Hegseth on whether classified information was posted to the unclassified Signal chat. Hegseth so far has not answered questions on whether the information he shared on Signal during that messaging was classified.

KNOWN: Hegseth has adamantly denied that “war plans” were texted on Signal, something that current and former U.S. officials called “semantics.” War plans carry a specific meaning. They often refer to the numbered and highly classified planning documents — sometimes thousands of pages long — that would inform U.S. decisions in case of a major conflict, such as if the United States is called to defend Taiwan.

But the information Hegseth did post — specific attack details selecting human and weapons storage targets — was a subset of those plans and was likely informed by the same classified intelligence. Posting those details to an unclassified app risked tipping off adversaries of the pending attack and could have put U.S. service members at risk, multiple U.S. officials said.

Sharing that information on a commercial app like Signal in advance of a strike “would be a violation of everything that we’re about,” said former Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel, who served under President Barack Obama.

NOT KNOWN: If anyone outside the messaging group got access to the Signal texts.

KNOWN: Hegseth is cracking down on unauthorized leaks of information inside the Defense Department, and his chief of staff issued a memo on March 21 saying the Pentagon would use polygraph tests to determine the sources of recent leaks, and prosecute those found to have disclosed unauthorized information.

NOT KNOWN: Whether Hegseth will take responsibility for the unauthorized release of national defense information to a journalist regarding the attack plans on the Houthis.

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth does a television interview outside the White House, Friday, March 21, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin)

Wearing a U.S. flag themed pocket square and belt buckle, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth waits for the start of a television interview outside the White House, Friday, March 21, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin)