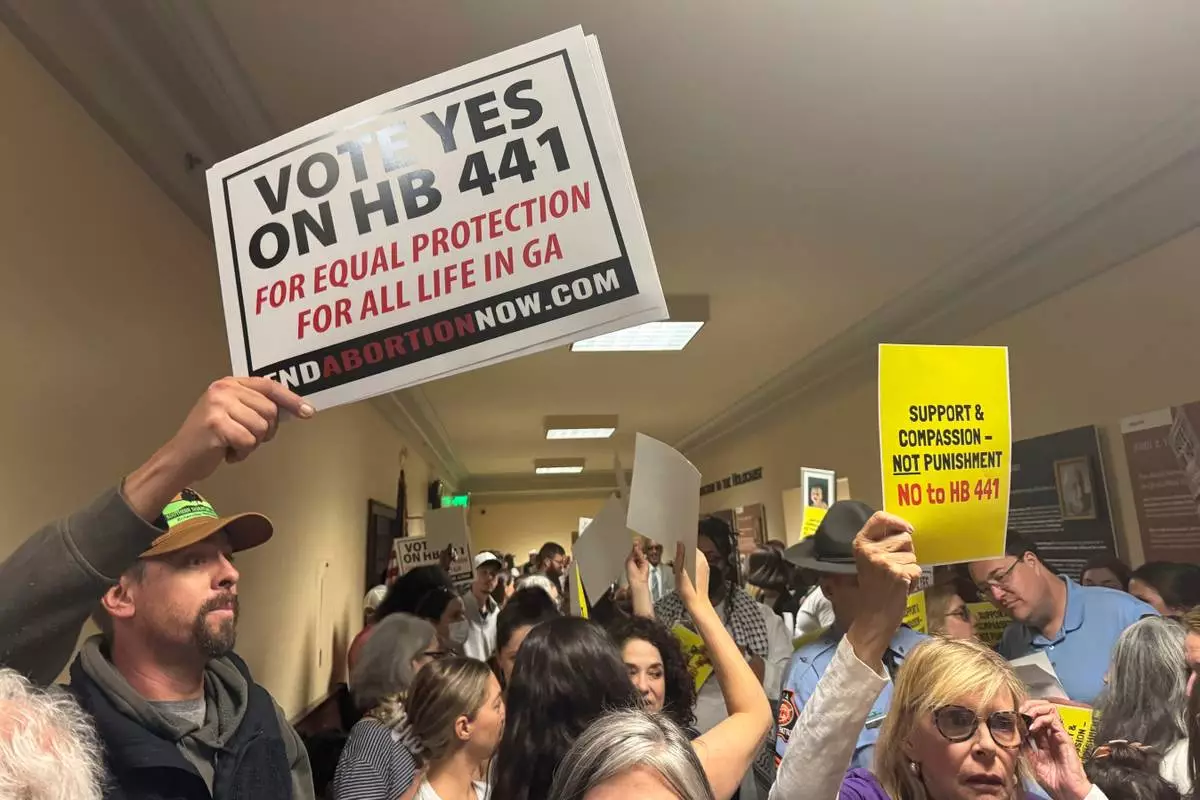

ATLANTA (AP) — A crowd of protesters on each side of the abortion debate flooded a windowless Georgia Capitol hallway Wednesday with chants and signs as lawmakers held a hearing on a bill that would ban the procedure in almost all cases.

Although the bill will not go anywhere this year because a deadline has passed for consideration by both chambers, the hearing granted by the House's Republican leadership gave anti-abortion activists a chance to speak out on an issue near and dear to their constituents.

Dozens milled about and shouted words of support or disdain for the proposal. Onlookers tried to squeeze into the hearing room as sheriff's deputies guarded the area. One man raised his voice above the noise and said, “I'm so thankful that my mom gave me life” and did not “sacrifice” her children.

Each time someone left the room after testifying, they were met with cheers from those on their side of the bill.

“Tens of thousands of babies made in the image of God continue to be murdered in our state every year, all within the bounds of the current law,” said bill sponsor Rep. Emory Dunahoo, a Gillsville Republican.

The bill would make most abortions a crime from the point of fertilization, at which point one would be considered a person, and classify the procedure as a homicide. It would expand Georgia’s broad “personhood” law, which gives rights such as tax breaks and child support to unborn children. At least five states have personhood laws.

Georgia already bans abortions after finding a “detectable human heartbeat,” which can happen as early as six weeks into pregnancy, when many women still don't know they are pregnant. Still, a flurry of religious leaders said the measure doesn't go far enough.

Some religious anti-abortion individuals were among the bill's opponents, though, saying it goes too far with criminalization.

Critics say the measure would bar women from lifesaving care during birth complications and in vitro fertilization. Many voiced concern that women with miscarriages or dangerous health complications would not get the care they need.

Rep. Shea Roberts, an Atlanta Democrat, recounted her own experience getting an abortion to save her life.

“It was one of the most devastating times in my life, and doctors told me that the dream of my child was going to die either inside of me or within minutes outside my body, and it would be suffering,” Roberts said.

The bill would grant some exceptions, including in cases involving a “spontaneous miscarriage” and procedures undertaken to save a woman's life "when accompanied by reasonable steps, if available, to save the life of her unborn child.”

But opponents say doctors would be too frightened to provide such care even when necessary. They pointed to the cases — reported by ProPublica — of two women who died from delayed care tied to Georgia's abortion law after taking abortion pills.

Doctors also noted that Georgia already has some of the nation’s highest maternal mortality rates, especially for Black women. Lawmakers should focus on helping them get more care, opponents said.

Doctors also said the bill sets the stage for the criminalization of in vitro fertilization and would force fertility clinics to close. The bill comes about a month after Georgia’s House passed a bill with bipartisan support to protect the right to in vitro fertilization. That measure was sponsored by Statesboro Republican Rep. Lehman Franklin, whose wife used IVF to conceive.

Dr. Karenne Fru, who runs a fertility clinic that provides in vitro fertilization, said the bill would put her out of work.

“My whole life is doing God's work. He said go forth and procreate,” Fru said, her voice shaking. “I'm doing that. Please just let me continue to do that. I cannot go to jail because I want to help people become parents.”

Kramon is a corps member for The Associated Press/Report for America Statehouse News Initiative. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues. Follow Kramon on X: @charlottekramon.

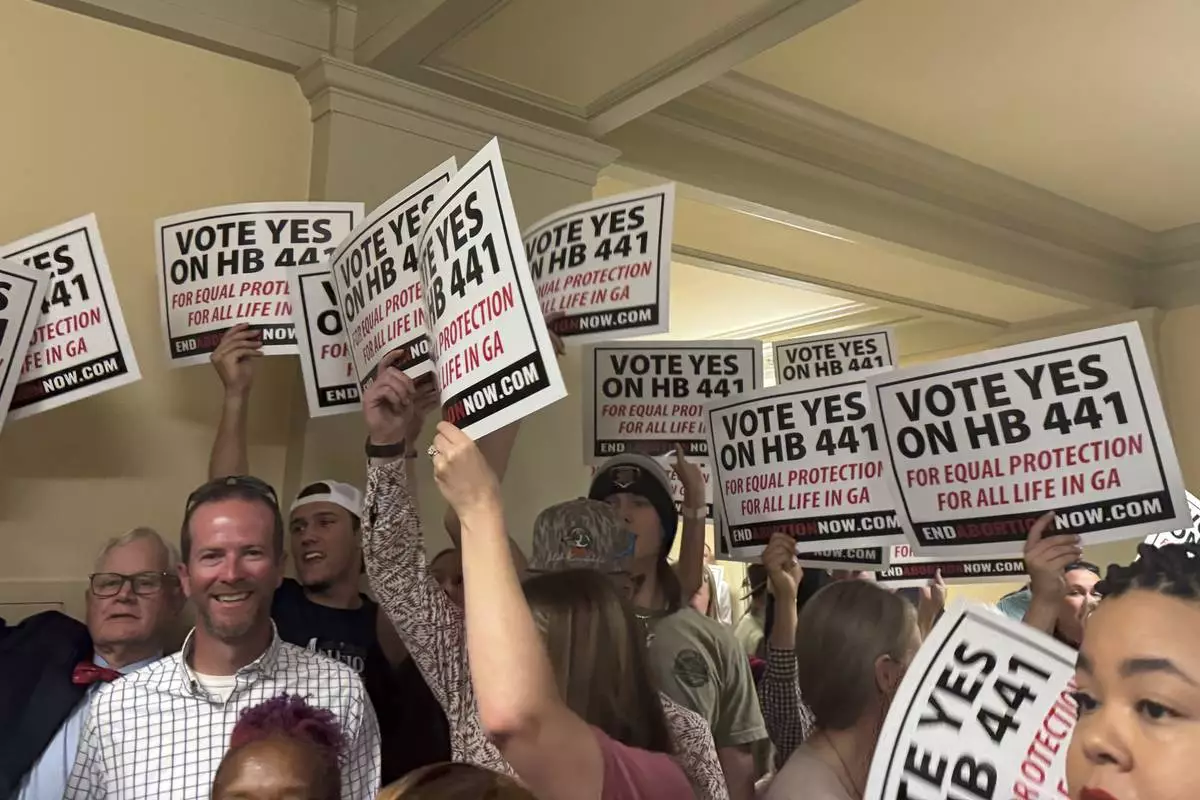

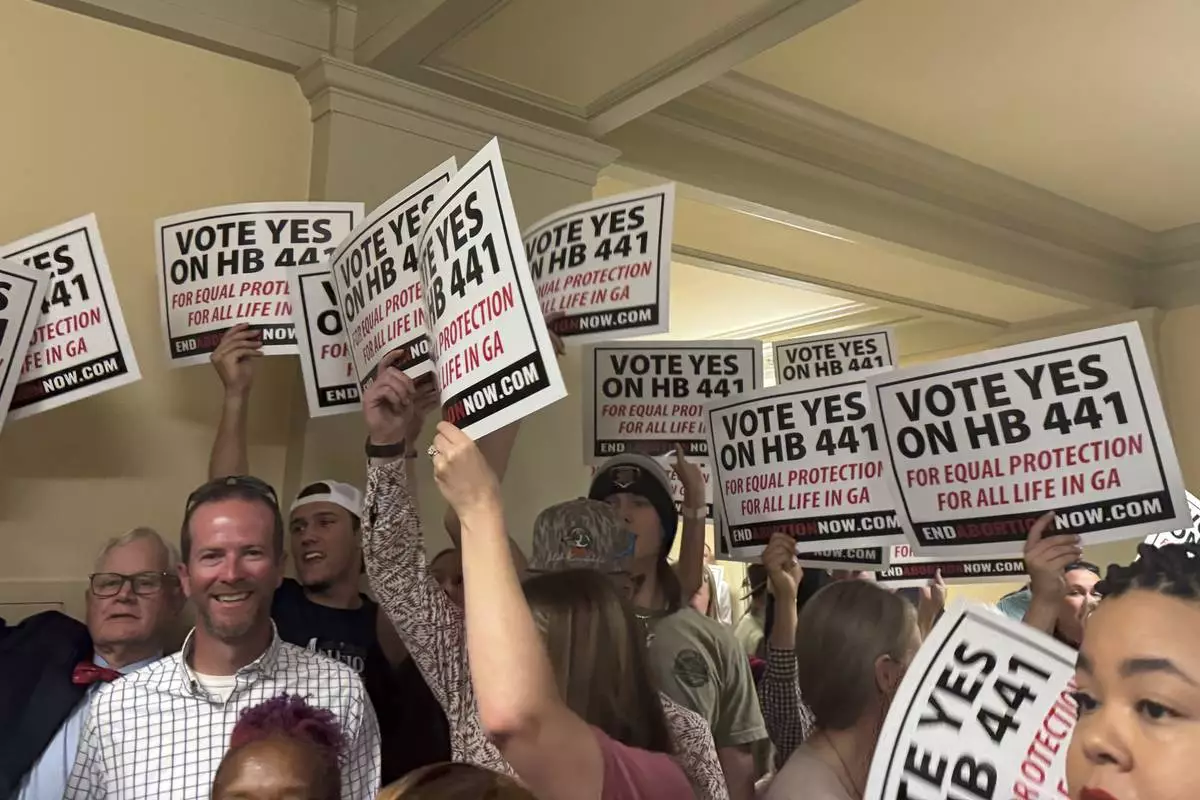

Anti-abortion protesters gather at the Georgia Capitol in Atlanta to support a total abortion ban on Wednesday, March 26, 2025. (AP Photo/Charlotte Kramon)

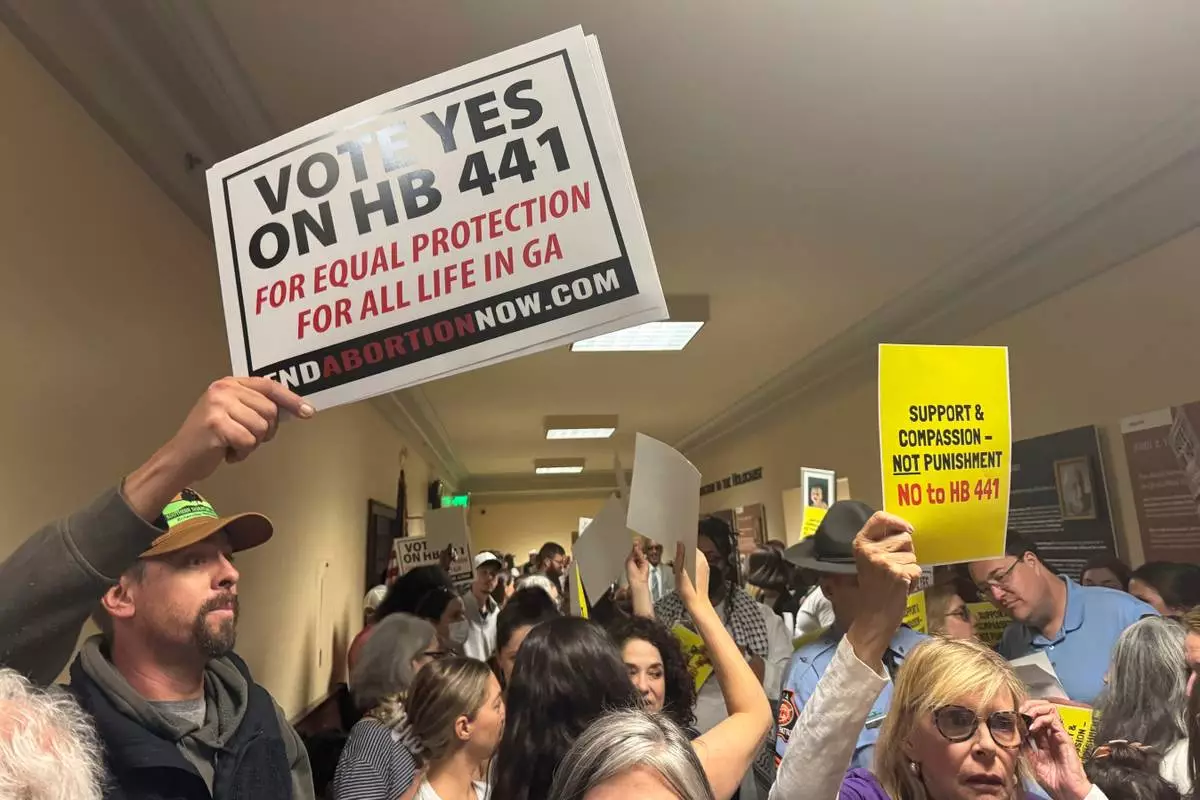

Protestors gather at the Georgia Capitol for a hearing on a bill that would ban all abortion in the state on Wednesday, March 26, 2025, in Atlanta. (AP Photo/Charlotte Kramon)

Demonstrators gather at the Georgia Capitol in Atlanta, Wednesday, March 26, 2025, to support and oppose a bill that would ban all abortion. (AP Photo/Charlotte Kramon)

WASHINGTON (AP) — A judge challenging the outcome of his North Carolina Supreme Court race was photographed wearing Confederate military garb and posing before a Confederate battle flag when he was a member of a college fraternity that glorified the pre-Civil War South.

The emergence of the photographs comes at a delicate time for Jefferson Griffin, a Republican appellate judge who is seeking a spot on North Carolina's highest court. Griffin, 44, is facing mounting criticism – including from some Republicans – as he seeks to invalidate over 60,000 votes cast in last November’s election, a still undecided contest in which he is trailing the Democratic incumbent by over 700 votes.

The photographs, which were obtained by The Associated Press, are from when Griffin was a student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill from 1999-2003 and a member of the Kappa Alpha Order, one of the oldest and largest fraternities in the U.S., with tens of thousands of alumni.

Griffin said he regretted donning the Confederate uniform, which was customary during the fraternity's annual “Old South” ball.

“I attended a college fraternity event that, in hindsight, was inappropriate and does not reflect the person I am today,” Griffin said in a statement. “At that time, like many college students, I did not fully grasp such participation’s broader historical and social implications. Since then, I have grown, learned, and dedicated myself to values that promote unity, inclusivity, and respect for all people.”

One of the pictures, taken during the 2001 ball, shows Griffin and roughly two-dozen other fraternity members clad in Confederate uniforms. Another photograph from the spring of 2000 shows Griffin and other Kappa Alpha brothers in front of a large Confederate flag. He served in 2002 as his chapter’s president.

Kappa Alpha has proven to be a lightning rod for controversy over the decades, often due to the racist or insensitive actions of some of its members. A number of politicians have been forced to apologize for having worn Confederate costumes at the fraternity's functions or for being photographed in front of a Confederate flag.

Griffin said Friday he voted in favor of a resolution prohibiting Kappa Alpha members from displaying the rebel battle flag at the group’s national convention in 2001. The fraternity didn’t ban the wearing of the Confederate uniforms until nearly a decade later, long after Griffin graduated.

“We believe in cultural humility, we respect the best parts of our organization’s history, and through education we challenge our members to work for a better future. These things are not mutually exclusive,” said Jesse Lyons, a spokesman for Kappa Alpha’s national office in Lexington, Virginia.

The fraternity claims Robert E. Lee as its “spiritual founder” and long championed the Southern “Lost Cause," a revisionist view of history that romanticizes the Confederacy and portrays the Civil War as a valiant struggle for “states’ rights” unrelated to the enslavement of Black people. In decades past, some Kappa Alpha chapters referred to themselves as a “klan,” a term that many viewed as an unsubtle wink to the Ku Klux Klan.

The photographs featuring Griffin were taken at a time when many other Kappa Alpha chapters were reevaluating their celebration of the Confederacy.

During Griffin’s time in the fraternity, some in his chapter questioned the appropriateness of dressing up in Confederate uniforms for the ball. Griffin opposed abandoning the tradition, according to a person familiar with the situation, who spoke on the condition of anonymity out of fear of reprisal. The uniforms stayed.

Griffin said he would “not respond to unsubstantiated comments based on memories of 20-plus years past.”

In high school Griffin also expressed an affinity for Robert E. Lee, the Confederate general who led southern forces during the Civil War. In a 1998 feature on high school “scholars of the week” in The News & Observer of Raleigh newspaper, Griffin said Lee was his No. 1 choice to include on an “ideal guest list” for a party.

The Kappa Alpha Order was founded in 1865, not long after Lee surrendered to the Union Army, at a Virginia college where Lee served as president. At least one of the first members was a former rebel soldier who had served under Lee, who is revered by the fraternity as the ideal of gentlemanly Southern chivalry.

For more than a century, Kappa Alpha threw “Old South” parties. They were formal affairs where the Confederate battle flag was flown and fraternity brothers dressed in replica Confederate gray uniforms and their dates wore antebellum-style hoop skirts. Sometimes they would ride through campus on horseback.

Some Kappa Alpha chapters, particularly in the South, clung to their traditions, including the wearing of blackface, even as they drew protests and public sentiment shifted.

A Kappa Alpha “Old South” parade at Alabama’s Auburn University in 1992 drew supporters waving Confederate battle flags, as well as counter protesters who burned them. In 1995, a group of Kappa Alpha members at the University of Memphis hurled racial slurs while beating a Black student who caused a disturbance outside a frat party, the Memphis Commercial Appeal reported at the time.

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill was no exception to the turmoil. Under pressure from student groups, the school's Kappa Alpha chapter in 1985 canceled its annual “Sharecropper’s Ball," which some attended in blackface. Fraternity members said blackface was worn because the event needed both Black and white attendees, but promised to discontinue the practice, according to a news story in the Daily Tar Heel student newspaper.

The Kappa Alpha chapter at North Carolina’s Wake Forest University stopped allowing members to wear Confederate uniform and display the Confederate flag in 1987.

But other chapters held on longer. It wasn't until Kappa Alpha members at the University of Alabama wore Confederate uniforms during a parade that paused in front of a Black sorority, which elicited intense blowback, that the national headquarters forbade them. It’s unclear if the chapter at UNC banned the uniforms before the national organization did.

Griffin is not the first public official to draw unwanted attention for their college-age embrace of symbols drawn from the darker chapters of the South's past.

Virginia's then-governor, Democrat Ralph Northam, came under intense criticism in 2019 over a racist photo that appeared on his yearbook page of his medical school. The incident led reporters to scour the college histories of other Southern leaders, forcing a number of politicians to publicly address their time as Kappa Alpha brothers.

Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves, then the state’s Republican lieutenant governor, dodged questions in 2019 about photos showing him wearing a Confederate uniform while he was a Kappa Alpha member at Millsaps College in the early 1990s. While Reeves was enrolled there in October 1994, other members of the fraternity were disciplined for wearing afro wigs and Confederate battle flags and shouting racial slurs at Black students, the AP reported at the time.

Republican South Carolina Gov. Henry McMaster declined to comment after yearbooks listed him as the leader of the fraternity's chapter at the University of South Carolina in 1969, along with photos of members wearing Confederate uniforms and posing with a rebel flag.

And Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee, also a Republican, expressed regret for participating in “Old South” parties as a student at Auburn University in the 1970s.

Contact AP’s global investigative team at Investigative@ap.org or https://www.ap.org/tips/

FILE - Judge Jefferson Griffin, the Republican candidate for the N.C. Supreme Court listens to testimony in Wake County Superior Court on Friday, February 7, 2025 in Raleigh, N.C. (Robert Willett/The News & Observer via AP, File)