JARAMANA, Syria (AP) — Rana Al-Ahmad opens her fridge after breaking fast at sundown with her husband and four children during the Islamic holy month of Ramadan.

Apart from eggs, potatoes and some bread, it’s empty because state electricity in Syria only comes two hours a day.

“We can’t leave our food in the fridge because it will spoil,” she said.

Her husband, a taxi driver in Damascus, is struggling to make ends meet, so the family can’t afford to install a solar panel in their two-room apartment in Jaramana on the outskirts of the capital.

Months after a lightning insurgency ended over half a century of the Assad dynasty’s rule in Syria, the Islamist interim government has been struggling to fix battered infrastructure after a 14-year conflict decimated much of the country. Severe electricity shortages continue to plague the war-torn country.

The United Nations estimates that 90% of Syrians live in poverty and the Syrian government has only been able to provide about two hours of electricity every day. Millions of Syrians, like Al-Ahmad and her family, can’t afford to pay hefty fees for private generator services or install solar panels.

Syria's new authorities under interim leader Ahmad Al-Sharaa have tried to ease the country's electricity crisis, but have been unable to stop the outages with patchwork solutions.

Even with a recent gas deal with Qatar and an agreement with Kurdish-led authorities that will give them access to Syria's oil fields, the country spends most of its days with virtually no power. Reports of oil shipments coming from Russia, a key military and political ally of Assad, shows the desperation.

At Al-Ahmad’s home, she and her husband were only able to get a small battery that could power some lights.

“The battery we have is small and its charge runs out quickly,” said Al-Ahmad, 37. It’s just enough that her children can huddle in the living room to finish their homework after school.

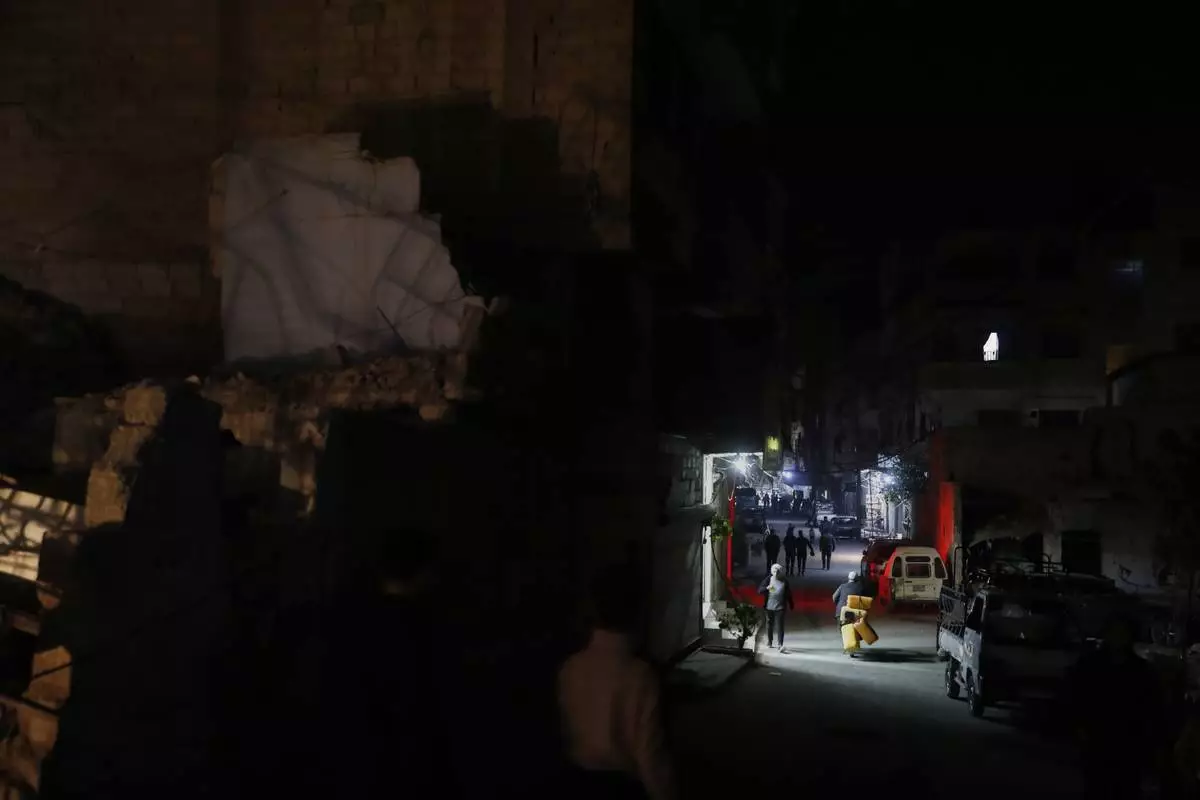

And the family is not alone. Everywhere in Syria, from Damascus to Daraa in the south, neighborhoods turn pitch black once the sun sets, lit only from street lamps, mosque minarets and car headlights.

The downfall of Assad in December brought rare hope to Syrians. But the new interim authorities have scrambled to establish control across the country and convince Western nations to lift economic sanctions to make its economy viable again.

The United States in January eased some restrictions for six months, authorizing some energy-related transactions. But it doesn’t appear to have made a significant difference on the ground just yet.

Washington and other Western governments face a delicate balance with Syria’s new authorities, and appear to be keen on lifting restrictions only if the war-torn country’s political transition is democratic and inclusive of Syrian civil society, women and non-Sunni Muslim communities.

Some minority groups have been concerned about the new authorities, especially incidents of revenge attacks targeting the Alawite community during a counter-offensive against an insurgency of Assad loyalists.

Fixing Syria’s damaged power plants and oil fields takes time, so Damascus is racing to get as much fuel as it can to produce more energy.

Damascus is now looking towards the northeastern provinces, where its oil fields under Kurdish-led authorities are to boost its capacity, especially after reaching a landmark ceasefire deal with them.

Political economist Karam Shaar said 85% of the country’s oil production is based in those areas, and Syria once exported crude oil in exchange for refined oil to boost local production, though the fields are battered and bruised from years of conflict.

These crucial oil fields fell into the hands of the extremist Islamic State group, which carved out a so-called caliphate across large swaths of Syria and Iraq from 2014 to 2017.

“It’s during that period where much of the damage to the (oil) sector happened,” said Shaar, highlighting intense airstrikes and fighting against the group by a U.S.-led international coalition.

After IS fell, the U.S.-backed Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces took control of key fields, leaving them away from the central government in Damascus. The new authorities hope to resolve this in a landmark deal with the SDF signed earlier this month.

Kamran Omar, who oversees oil production in the Rmeilan oil fields in the northeastern city of Hassakeh, says shortages in equipment and supplies and clashes that persisted with Turkey and Turkish-backed forces have slowed down production, but told the AP that some of that production will eventually go to households and factories in other parts of Syria.

The fields only produce a fraction of what they once did. The Rmeilan field sends just 15,000 of the approximately 100,000 barrels they produce to other parts of Syria to ease some of the burden on the state.

The authorities in Damascus also hope that a recent deal with Qatar that would supply them with gas through Jordan to a major plant south of the capital will be the first of more agreements.

Syria's authorities have not acknowledged reports of Russia sending oil shipments to the country. Moscow once aided Assad in the conflict against armed Islamist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham that toppled the former president, but this shows that they are willing to stock up on fuel from whoever is offering.

Interim Electricity Minister Omar Shaqrouq admitted in a news conference that bringing back electricity to Syrian homes 24 hours a day is not on the horizon.

“It will soon be four hours, but maybe some more in the coming days.”

Increasing that supply will be critical for the battered country, which hopes to ease the economic woes of millions and bring about calm and stability. Shaar, who has visited and met with Syria’s new authorities, says that the focus on trying to bring fuel in the absence of funding for major infrastructural overhauls is the best Damascus can do given how critical the situation is.

“Electricity is the cornerstone of economic recovery,” said Shaar. “Without electricity you can’t have a productive sector, (or any) meaningful industries.”

Chehayeb reported from Beirut. Associated Press journalist Hogir El Abdo reported from Hassakeh, Syria.

Tankers line up as they prepare to head to the rural areas where oil and gas fields are located in the outskirts Qamishli, northeast Syria, Saturday, March 22, 2025. Damascus is urgently working to secure as much fuel as possible to increase energy production, focusing on the country's northeastern provinces, where oil fields controlled by Kurdish-led authorities could help boost its capacity after a landmark ceasefire deal with them.(AP Photo/Baderkhan Ahmad)

A worker operates a makeshift refinery on the outskirts of Qamishli, northeast Syria, Saturday, March 22, 2025, where oil is refined into gasoline and other products like diesel. Damascus is urgently working to secure as much fuel as possible to increase energy production, focusing on the country's northeastern provinces, where oil fields controlled by Kurdish-led authorities could help boost capacity after a landmark ceasefire deal with them. (AP Photo/Baderkhan Ahmad)

Smoke rises from a tank used as makeshift refinery on the outskirts of Qamishli, northeast Syria, Saturday, March 22, 2025, where oil is refined into gasoline and other products like diesel. Damascus is urgently working to secure as much fuel as possible to increase energy production, focusing on the country's northeastern provinces, where oil fields controlled by Kurdish-led authorities could help boost capacity following a landmark ceasefire deal with them. (AP Photo/Baderkhan Ahmad)

Tankers line up as they prepare to head to the rural areas where oil and gas fields are located in the outskirts Qamishli, northeast Syria, Saturday, March 22, 2025. Damascus is urgently working to secure as much fuel as possible to increase energy production, focusing on the country's northeastern provinces, where oil fields controlled by Kurdish-led authorities could help boost its capacity after a landmark ceasefire deal with them.(AP Photo/Baderkhan Ahmad)

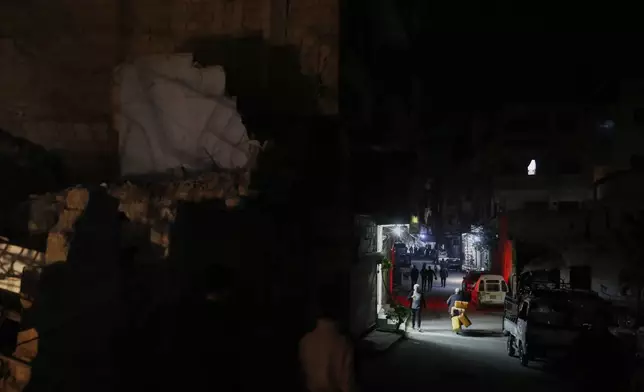

Lights illuminate a few windows of a damaged building in Damascus, Syria, early Thursday, March 27, 2025. In most neighborhoods across the country, areas plunge into darkness once the sun sets, forcing many residents to pay high fees for private generator services or install solar panels. (AP Photo/Omar Sanadiki)

Residents walk along a poorly illuminated street in Damascus, Syria, early Thursday March 27, 2025. Neighborhoods in most parts of the country turn pitch black once the sunsets, save on some lights from street lamps, Mosque minarets, and drivers with their floodlights on to see.(AP Photo/Omar Sanadiki)

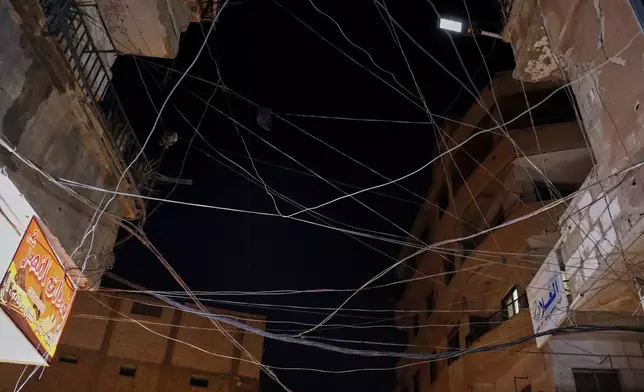

Electricity cables hang across a street in Damascus, Syria, early Thursday March 27, 2025. Neighborhoods in most parts of the country turn pitch black once the sunsets, save on some lights from street lamps, Mosque minarets, and drivers with their floodlights on to see.(AP Photo/Omar Sanadiki)

A truck sits on the side of a road as a car drives by along an otherwise dark road in the outskirts of Damascus, Syria, early Thursday March 27, 2025. Neighborhoods in most parts of the country turn pitch black once the sunsets, save on some lights from street lamps, Mosque minarets, and drivers with their floodlights on to see.(AP Photo/Omar Sanadiki)

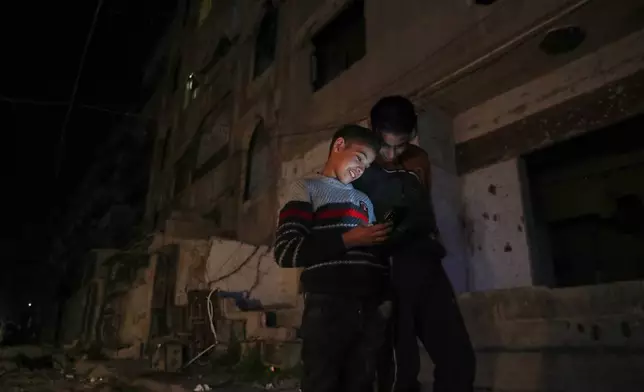

Two boys look at a cellphone in a dark street in Damascus, Syria, early Thursday March 27, 2025. Neighborhoods in most parts of the country turn pitch black once the sunsets, save on some lights from street lamps, Mosque minarets, and drivers with their floodlights on to see.(AP Photo/Omar Sanadiki)