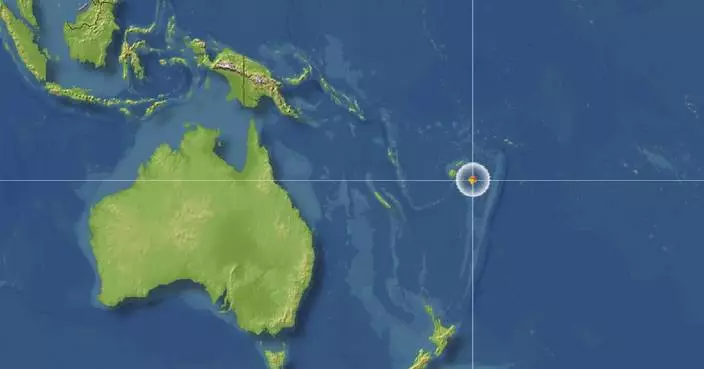

Early Friday, a major 7.7 magnitude earthquake that originated near Mandalay, Myanmar, shook the Earth as far as Bangkok, about 800 miles (1,300 kilometers) away.

Two hard-hit cities in Myanmar suffered extensive damage, with images from the capital, Naypyidaw, showing rescue crews pulling victims from the rubble of collapsed buildings. Authorities in Bangkok said deaths had occurred at three construction sites, including a high-rise that collapsed.

Click to Gallery

People who evacuated from buildings following earthquake in Bangkok, Thailand, Friday, March 28, 2025. (AP Photo/Chutima Lalit)

In this image provided by The Myanmar Military True News Information Team, Myanmar's military leader Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, center, inspects damaged road caused by an earthquake Friday, March 28, 2025, in Naypyitaw, Myanmar. (The Myanmar Military True News Information Team via AP)

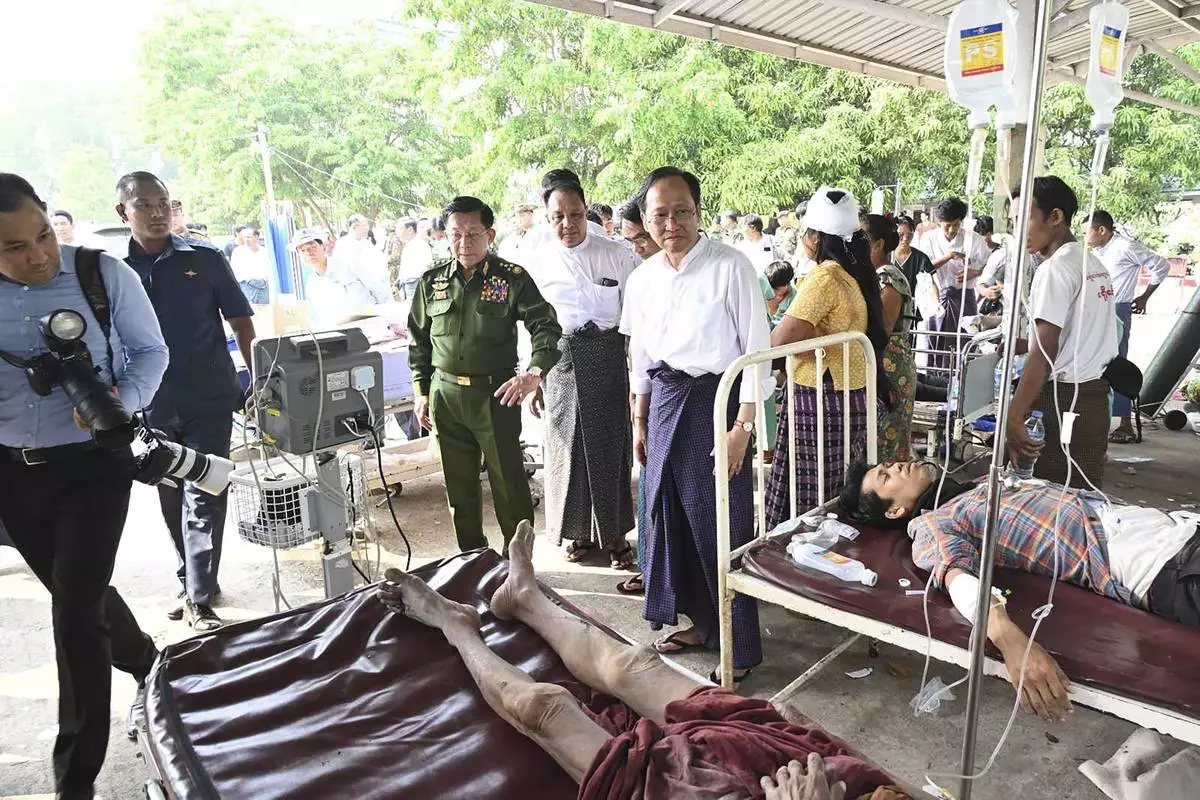

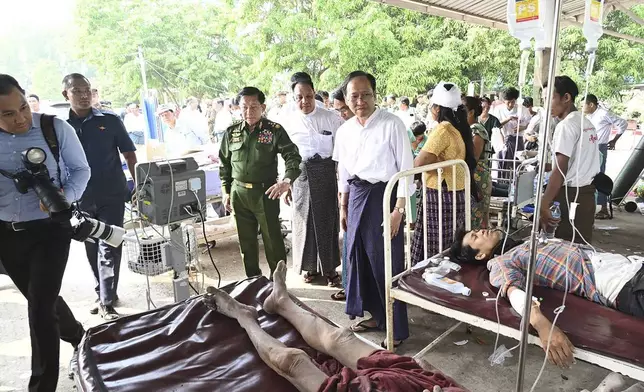

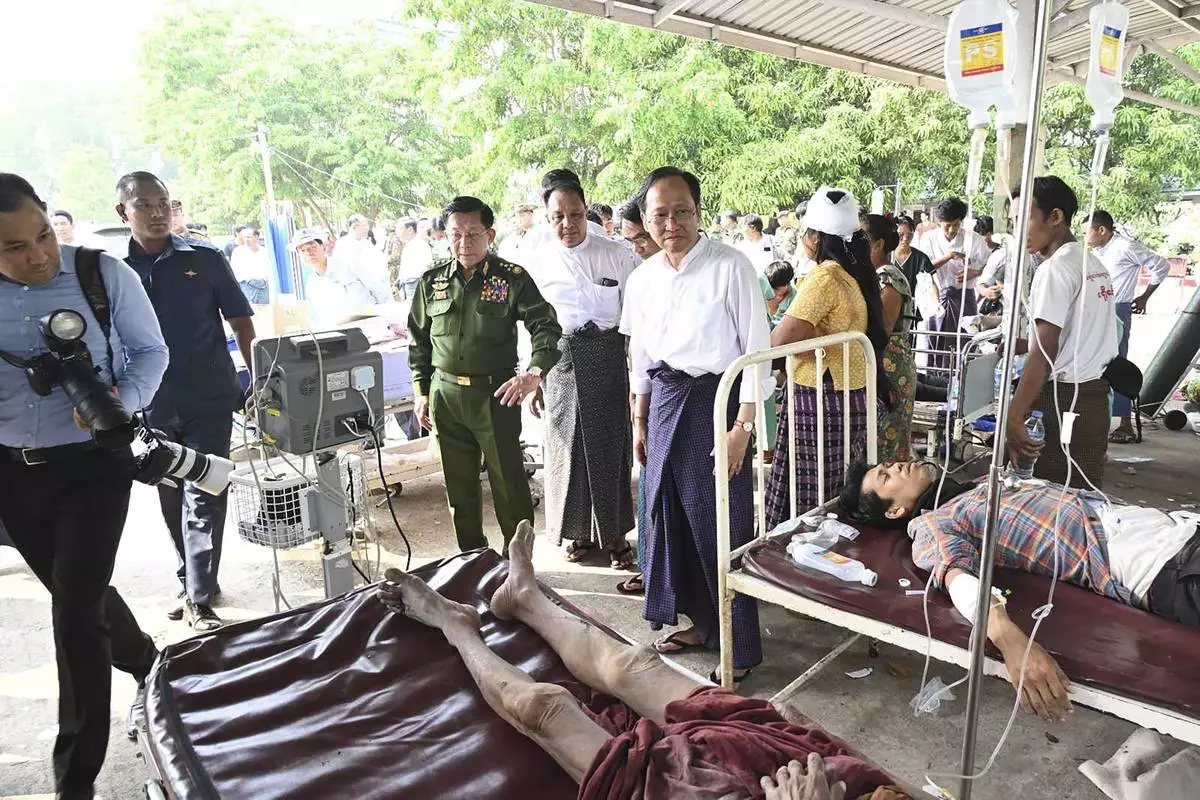

In this image provided by The Myanmar Military True News Information Team, Myanmar's military leader Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, center, inspects victims caused by an earthquake Friday, March 28, 2025, in Naypyitaw, Myanmar. (The Myanmar Military True News Information Team via AP)

In this image provided by The Myanmar Military True News Information Team, a soldier provide security while vehicles make their ways near damaged road caused by an earthquake Friday, March 28, 2025, in Naypyitaw, Myanmar. (The Myanmar Military True News Information Team via AP)

Rescuers work at the site a high-rise building under construction that collapsed after a 7.7 magnitude earthquake in Bangkok, Thailand, Friday, March 28, 2025. (AP Photo/Wason Wanichakorn)

Volunteers look for survivors near a damaged building Friday, March 28, 2025, in Naypyitaw, Myanmar. (AP Photo/Aung Shine Oo)

Experts say the earthquake, which occurred along the Sagaing Fault, was close to the Earth's surface, generating intense seismic forces. Preliminary estimates by the U.S. Geological Survey show that nearly 800,000 people in Myanmar may have been within the zone of the most violent shaking and that death tolls exceeding 1,000 people, and perhaps much higher, are probable.

The Earth's crust is broken up into several pieces called tectonic plates, which fit together like a jigsaw puzzle.

This formation is “mostly stable, but along the edges they are moving,” Columbia University geophysicist Michael Steckler said.

Pressure builds up when sliding plates get stuck, increasing “very slowly for decades or for hundreds of years, and then all of a sudden the rock plates will jump," triggering shaking that causes an earthquake, Steckler said.

Earthquakes typically occur along edges of tectonic plates. But their impacts may be felt in a broader region.

Earthquakes that occur in the ocean don't always attract attention, but those that occur close to where people live can cause deaths and injuries, most often from collapsed buildings.

Scientists have a good idea of where earthquakes are likely to occur, "but we can't predict when they'll occur,” USGS seismologist Will Yeck said.

However, after the initial big earthquake, researchers are able to project that other smaller earthquakes nearby, called aftershocks, are likely.

Aftershocks are triggered “because of changes to stress in the Earth from the main shock,” Yeck said.

Given the magnitude of the quake in Myanmar, “you will probably see aftershocks for the next several months,” Steckler said.

In regions of the world with known active fault lines, including California and Japan, building codes are often designed to withstand earthquakes. But that's not true everywhere.

“If you feel shaking, the guidance depends on where you are in the world,” Yeck said.

In many countries, including the United States, if you're inside when an earthquake occurs, it's advisable to drop to the ground, cover your head — for example, by crawling under a desk or other sturdy structure — and hold onto that structure, he said. Try to avoid areas near glass windows and don't use building elevators.

If you're outside, try to remain in an area away from buildings or trees that could fall.

Depending on the location, there may be secondary hazards triggered by earthquakes, such as landslides, fires or tsunamis, he said.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

People who evacuated from buildings following earthquake in Bangkok, Thailand, Friday, March 28, 2025. (AP Photo/Chutima Lalit)

In this image provided by The Myanmar Military True News Information Team, Myanmar's military leader Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, center, inspects damaged road caused by an earthquake Friday, March 28, 2025, in Naypyitaw, Myanmar. (The Myanmar Military True News Information Team via AP)

In this image provided by The Myanmar Military True News Information Team, Myanmar's military leader Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, center, inspects victims caused by an earthquake Friday, March 28, 2025, in Naypyitaw, Myanmar. (The Myanmar Military True News Information Team via AP)

In this image provided by The Myanmar Military True News Information Team, a soldier provide security while vehicles make their ways near damaged road caused by an earthquake Friday, March 28, 2025, in Naypyitaw, Myanmar. (The Myanmar Military True News Information Team via AP)

Rescuers work at the site a high-rise building under construction that collapsed after a 7.7 magnitude earthquake in Bangkok, Thailand, Friday, March 28, 2025. (AP Photo/Wason Wanichakorn)

Volunteers look for survivors near a damaged building Friday, March 28, 2025, in Naypyitaw, Myanmar. (AP Photo/Aung Shine Oo)

SEOUL, South Korea (AP) — South Korea’s Constitutional Court will rule Friday on whether to formally dismiss or reinstate impeached President Yoon Suk Yeol — a decision that either way will likely deepen domestic divisions.

The court has been deliberating his political fate after conservative Yoon was impeached by the liberal opposition-controlled National Assembly in December over his brief imposition of martial law that has triggered a massive political crisis.

Millions of people have rallied around the country to support or denounce Yoon. Police said they’ll mobilize all available personnel to preserve order and respond to possible acts of vandalism, arson and assault before and after the court's ruling.

The Constitutional Court said in a brief statement Tuesday that it would issue its ruling at 11 a.m. Friday and that it will be broadcast live.

Removing Yoon from office requires support from at least six of the court's eight justices. If the court rules against Yoon, South Korea must hold an election within two months for a new president. If the court overturns his impeachment, Yoon would immediately return to his presidential duties.

Jo Seung-lae, a spokesperson for the main liberal opposition Democratic Party which led Yoon's impeachment, called for the court to “demonstrate its firm resolve” to uphold the constitutional order by dismissing Yoon. Kwon Youngse, leader of Yoon’s People Power Party, urged the court’s justices to “consider the national interest” and produce a decision that is “strictly neutral and fair.”

Many observers earlier predicted the court’s verdict would come in mid-March based on the timing of its ruling in past presidential impeachments. The court hasn’t explained why it takes longer time for Yoon's case, sparking rampant speculation on his political fate.

At the heart of the matter is Yoon’s decision to send hundreds of troops and police officers to the National Assembly after imposing martial law on Dec. 3. Yoon has insisted that he aimed to maintain order, but some military and military officials testified Yoon ordered them to drag out lawmakers to frustrate a floor vote on his decree and detain his political opponents.

Yoon argues that he didn’t intend to maintain martial law for long, and he only wanted to highlight what he called the “wickedness” of the Democratic Party, which obstructed his agenda, impeached senior officials and slashed his budget bill. During his martial law announcement, he called the assembly “a den of criminals” and “anti-state forces.”

By law, a president has the right to declare martial law in wartime or other emergency situations, but the Democratic Party and its supporters say South Korea wasn’t in such a situation.

The impeachment motion accused Yoon of suppressing National Assembly activities, attempting to detain politicians and others and undermining peace in violation of the constitution and other laws. Yoon has said he had no intention of disrupting National Assembly operations and detaining anyone.

Martial law lasted only six hours because lawmakers managed to enter the assembly and vote to strike down his decree unanimously. No violence erupted, but live TV footage showing armed soldiers arriving at the assembly invoked painful memories of past military-backed dictatorships. It was the first time for South Korea to be placed under martial law since 1980.

Earlier public surveys showed a majority of South Koreans supported Yoon’s impeachment. But after his impeachment, pro-Yoon rallies have grown sharply, with many conservatives fed up with what they call the Democratic Party’s excessive offensive on the already embattled Yoon administration.

In addition to the Constitutional Court’s ruling on his impeachment, Yoon was arrested and indicted in January on criminal rebellion charges.Yoon was released from prison March 8, after a Seoul district court cancelled his arrest and allowed him to stand his criminal trial without being detained.

Ten top military and police officials have also been arrested and indicted over their roles in the martial law enactment.

__

Associated Press writer Kim Tong-hyung contributed to this report.

Police officers stand guard to block an anticipated farmers' march calling for impeached South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol to step down in Seoul, South Korea, Tuesday, March 25, 2025.(AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

Supporters of impeached South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol stage a rally to oppose his impeachment in Seoul, South Korea, Saturday, March 29, 2025. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

Supporters of impeached South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol attend a rally to oppose his impeachment in Seoul, South Korea, Saturday, March 29, 2025. The letters read "Yoon Suk Yeol's immediate return." (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

Protesters stage a rally calling for impeached South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol to step down in Seoul, South Korea, Saturday, March 29, 2025. The banners read "Dismiss Yoon Suk Yeol." (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

FILE - Impeached South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol greets his supporters as he comes out of a detention center in Uiwang, South Korea, on March 8, 2025. (Kim Do-hun/Yonhap via AP, File)

FILE - South Korea's impeached President Yoon Suk Yeol attends a hearing of his impeachment trial at the Constitutional Court in Seoul, South Korea, on Feb. 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man, Pool, File)

A protester wearing a mask of impeached South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol attends a march during a rally calling for Yoon to step down in Seoul, South Korea, Saturday, March 29, 2025. The banner reads "Dismiss Yoon Suk Yeol." (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)