NEW YORK (AP) — The basketball season is over, but St. John's forward Zuby Ejiofor is still heeding coach Rick Pitino’s advice.

The 6-foot-9 Ejiofor, who earned first-team All-Big East honors last month after helping the Johnnies to their first outright regular-season conference title in 40 years, threw out the first pitch at Citi Field on Wednesday before the series finale between the New York Mets and Miami Marlins.

“He gave me a little advice,” Ejiofor said of Pitino, who threw out the first pitch before a Mets-Yankees game in 2023. “He said not to bounce it.”

Despite saying he had “zero” experience in baseball, Ejiofor threw a pitch from the top of the mound that landed right in the glove of John Franco, the St. John’s alum and former Mets closer who stood at the plate in front of eight of Ejiofor’s teammates.

“If Zuby takes care of business and doesn’t hurt our superstar alumnus here, it’ll be a good start for the Mets, the hottest team in baseball,” Pitino said before New York lost 5-0, snapping its six-game winning streak.

Pitino — wearing a personalized No. 41 jersey, the same number retired by the Mets in Tom Seaver’s honor — appeared with Ejiofor, Franco and Red Storm center Vince Iwuchukwu at a pregame news conference. Franco was presented with a St. John’s No. 45 uniform — the same number he wore in his final six-plus seasons with the Mets.

The 72-year-old Pitino, raised in New York City and Long Island, recalled going to Yankees games as a child with his sisters but also said he cheered for the Mets.

“I used to go watch Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris, reserves like Héctor López, Johnny Blanchard, (Tony) Kubek, (Bobby) Richardson,” Pitino said. “But I was also a Mets fan of (Jerry) Koosman, Seaver and going back to Tommie Agee. I’m one of the few people that rooted for both teams. Anything with ‘NY’ on it, I’m 100% behind it.”

Mets manager Carlos Mendoza said he enjoyed watching as St. John’s became the biggest winter sports story in New York by going 31-5 and winning an NCAA Tournament game for the first time since 2000. The Red Storm matched a school record for wins and took home their first Big East Tournament title in 25 years before their season ended with a 75-66 loss to Arkansas in the second round of the NCAAs.

“When you get a team that is doing something special like they did — we saw it last year with us, it was our story where nobody knew if we were able to do anything,” said Mendoza, who led the Mets to the 2024 National League Championship Series after a 24-35 start. “It’s a pretty cool feeling. It’s a privilege, it’s an honor, when you have the ability to represent and do something special the way they did.”

Pitino said he’s looking forward to getting back to work with the Red Storm, who have added former Providence star Bryce Hopkins and ex-Arizona State guard Joson Sanon via the transfer portal. Red Storm star RJ Luis Jr., the Big East Player of the Year and a second-team All-American, decided to declare for the NBA draft while retaining his eligibility and entering the portal.

Pitino acknowledged St. John’s needs to improve offensively in order to become a national title contender. The Red Storm finished second in the nation in defensive efficiency but 68th in offensive efficiency, per KenPom.com. Each of the teams that made the Final Four — NCAA champion Florida along with Houston, Duke and Auburn — finished in the top 10 in offensive efficiency.

“We need shooting as much as anything,” Pitino said of the Red Storm, who shot 44.5% from the field and ranked among the nation’s bottom 20 teams in 3-point shooting at 30.1%. “It’s the offensive teams that really go far in the tournament. You have to have a great offense. And we were not a great offensive basketball team this season.”

This story has been corrected with the proper spelling of Tommie Agee’s first name and Héctor López's last name. A previous version was corrected to show that Pitino was referring to Bobby Richardson, not Clint Richardson.

AP MLB: https://apnews.com/hub/mlb

St. John's men's basketball coach Rick Pitino speaks at a press conference before a baseball game between the Miami Marlins and the New York Mets, Wednesday, April 9, 2025, in New York. (AP Photo/Pamela Smith)

St. John's men's basketball coach Rick Pitino, center left, speaks at a press conference alongside forward Zuby Ejiofor, left, John Franco, center right, and center Vince Iwuchukwu, right, before a baseball game between the Miami Marlins and the New York Mets, Wednesday, April 9, 2025, in New York. (AP Photo/Pamela Smith)

St. John's men's basketball player Zuby Ejiofor gets set to throw out a ceremonial first pitch before a baseball game between the New York Mets and the Miami Marlins, Wednesday, April 9, 2025, in New York. (AP Photo/Pamela Smith)

WASHINGTON (AP) — When the Justice Department lifted a school desegregation order in Louisiana this week, officials called its continued existence a “historical wrong” and suggested that others dating to the Civil Rights Movement should be reconsidered.

The end of the 1966 legal agreement with Plaquemines Parish schools announced Tuesday shows the Trump administration is “getting America refocused on our bright future,” Assistant Attorney General Harmeet Dhillon said.

Inside the Justice Department, officials appointed by President Donald Trump have expressed desire to withdraw from other desegregation orders they see as an unnecessary burden on schools, according to a person familiar with the issue who was granted anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly.

Dozens of school districts across the South remain under court-enforced agreements dictating steps to work toward integration, decades after the Supreme Court struck down racial segregation in education. Some see the court orders' endurance as a sign the government never eradicated segregation, while officials in Louisiana and at some schools see the orders as bygone relics that should be wiped away.

The Justice Department opened a wave of cases in the 1960s, after Congress unleashed the department to go after schools that resisted desegregation. Known as consent decrees, the orders can be lifted when districts prove they have eliminated segregation and its legacy.

The Trump administration called the Plaquemines case an example of administrative neglect. The district in the Mississippi River Delta Basin in southeast Louisiana was found to have integrated in 1975, but the case was to stay under the court’s watch for another year. The judge died the same year, and the court record “appears to be lost to time,” according to a court filing.

“Given that this case has been stayed for a half-century with zero action by the court, the parties or any third-party, the parties are satisfied that the United States’ claims have been fully resolved,” according to a joint filing from the Justice Department and the office of Louisiana Attorney General Liz Murrill.

Plaquemines Superintendent Shelley Ritz said Justice Department officials still visited every year as recently as 2023 and requested data on topics including hiring and discipline. She said the paperwork was a burden for her district of fewer than 4,000 students.

“It was hours of compiling the data,” she said.

Louisiana “got its act together decades ago,” said Leo Terrell, senior counsel to the Civil Rights Division at the Justice Department, in a statement. He said the dismissal corrects a historical wrong, adding it’s “past time to acknowledge how far we have come.”

Murrill asked the Justice Department to close other school orders in her state. In a statement, she vowed to work with Louisiana schools to help them “put the past in the past.”

Civil rights activists say that's the wrong move. Many orders have been only loosely enforced in recent decades, but that doesn't mean problems are solved, said Johnathan Smith, who worked in the Justice Department's Civil Rights Division during President Joe Biden's administration.

“It probably means the opposite — that the school district remains segregated. And in fact, most of these districts are now more segregated today than they were in 1954," said Smith, who is now chief of staff and general counsel for the National Center for Youth Law.

More than 130 school systems are under Justice Department desegregation orders, according to records in a court filing this year. The vast majority are in Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi, with smaller numbers in states like Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina. Some other districts remain under separate desegregation agreements with the Education Department.

The orders can include a range of remedies, from busing requirements to district policies allowing students in predominately Black schools to transfer to predominately white ones. The agreements are between the school district and the U.S. government, but other parties can ask the court to intervene when signs of segregation resurface.

In 2020, the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund invoked a consent decree in Alabama’s Leeds school district when it stopped offering school meals during the COVID-19 pandemic. The civil rights group said it disproportionately hurt Black students, in violation of the desegregation order. The district agreed to resume meals.

Last year, a Louisiana school board closed a predominately Black elementary school near a petrochemical facility after the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund said it disproportionately exposed Black students to health risks. The board made the decision after the group filed a motion invoking a decades-old desegregation order at St. John the Baptist Parish.

The dismissal has raised alarms among some who fear it could undo decades of progress. Research on districts released from orders has found that many saw greater increases in racial segregation compared with those under court orders.

“In very many cases, schools quite rapidly resegregate, and there are new civil rights concerns for students,” said Halley Potter, a senior fellow at The Century Foundation who studies educational inequity.

Ending the orders would send a signal that desegregation is no longer a priority, said Robert Westley, a professor of antidiscrimination law at Tulane University Law School in New Orleans.

“It’s really just signaling that the backsliding that has started some time ago is complete," Westley said. “The United States government doesn’t really care anymore of dealing with problems of racial discrimination in the schools. It’s over.”

Any attempt to drop further cases would face heavy opposition in court, said Raymond Pierce, president and CEO of the Southern Education Foundation.

“It represents a disregard for education opportunities for a large section of America. It represents a disregard for America’s need to have an educated workforce," he said. “And it represents a disregard for the rule of law.”

Associated Press writer Sharon Lurye contributed from New Orleans.

This story has been corrected to reflect the group that invoked desegregation orders in other Louisiana districts is the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, not the NAACP.

The Associated Press’ education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

FILE - Louisiana Attorney General Liz Murrill speaks to reporters, Jan. 1, 2025, in New Orleans. (AP Photo/Matthew Hinton, file)

FILE - Children smile from window of a school bus in Springfield, Mass., as court-ordered busing brought Black children and white children together in elementary grades without incident, Sept. 16, 1974. (AP Photo/Peter Bregg, File)

FILE - White and Black children mix freely on the playground outside a school in a racially mixed neighborhood, Oct. 18, 1957, in Detroit. (AP Photo/Alvan Quinn, File)

FILE - Students from Charlotte High School in Charlotte, N.C., ride a bus together, May 15, 1972. (AP Photo/Harold L. Valentine, File)

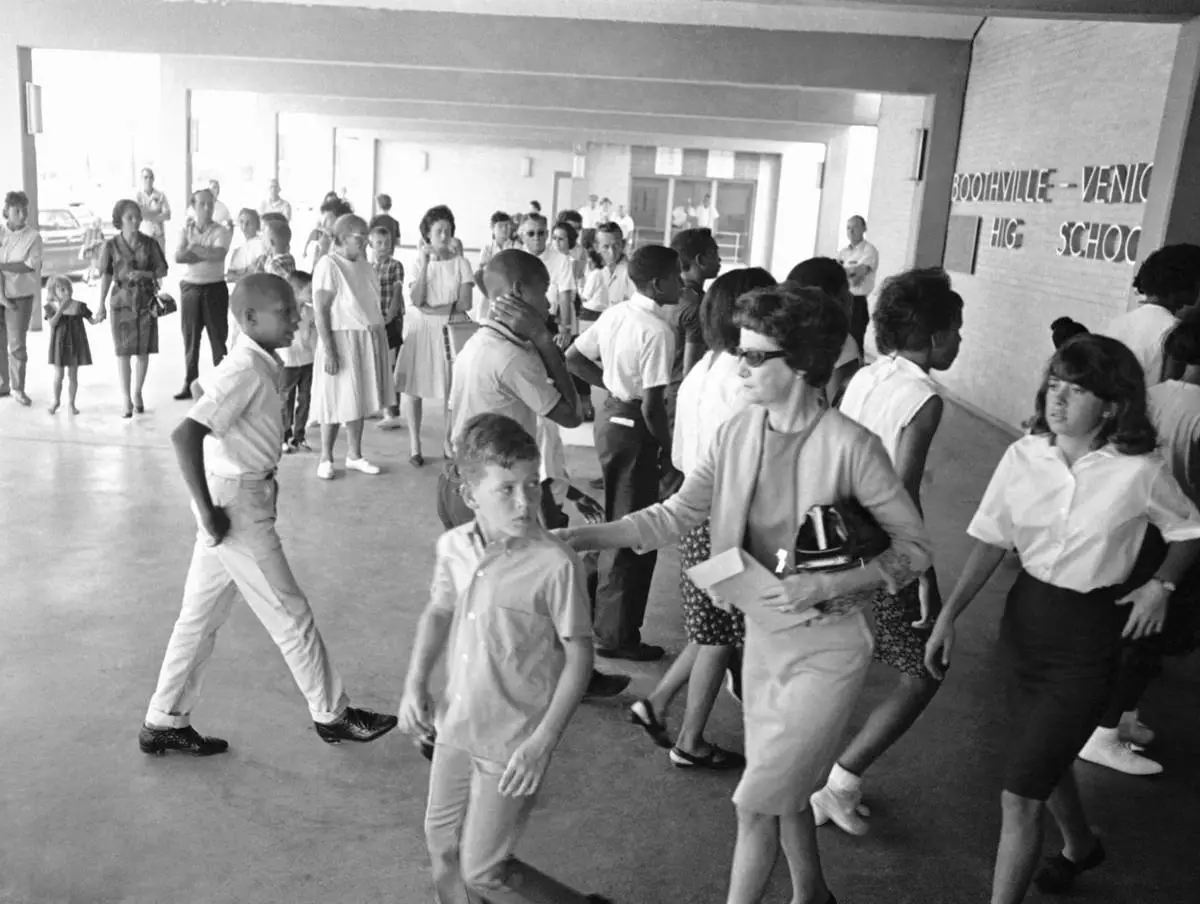

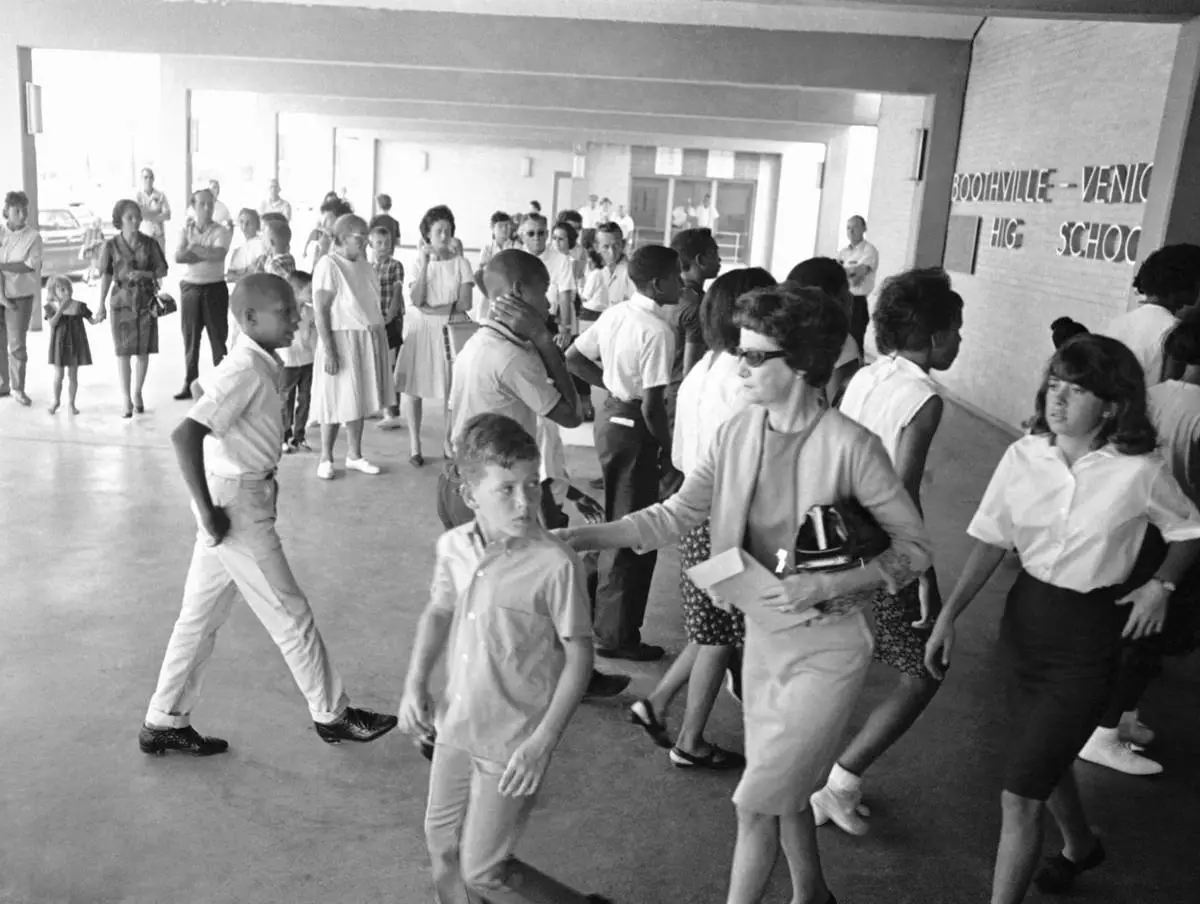

FILE - A white mother walks with her son past a group of African American students arriving for classes at formerly all-white Boothville Venice High School on Monday, Sept. 12, 1966 as racial barriers fell in Plaquemines Parish. (AP Photo/Jack Thornell, file)

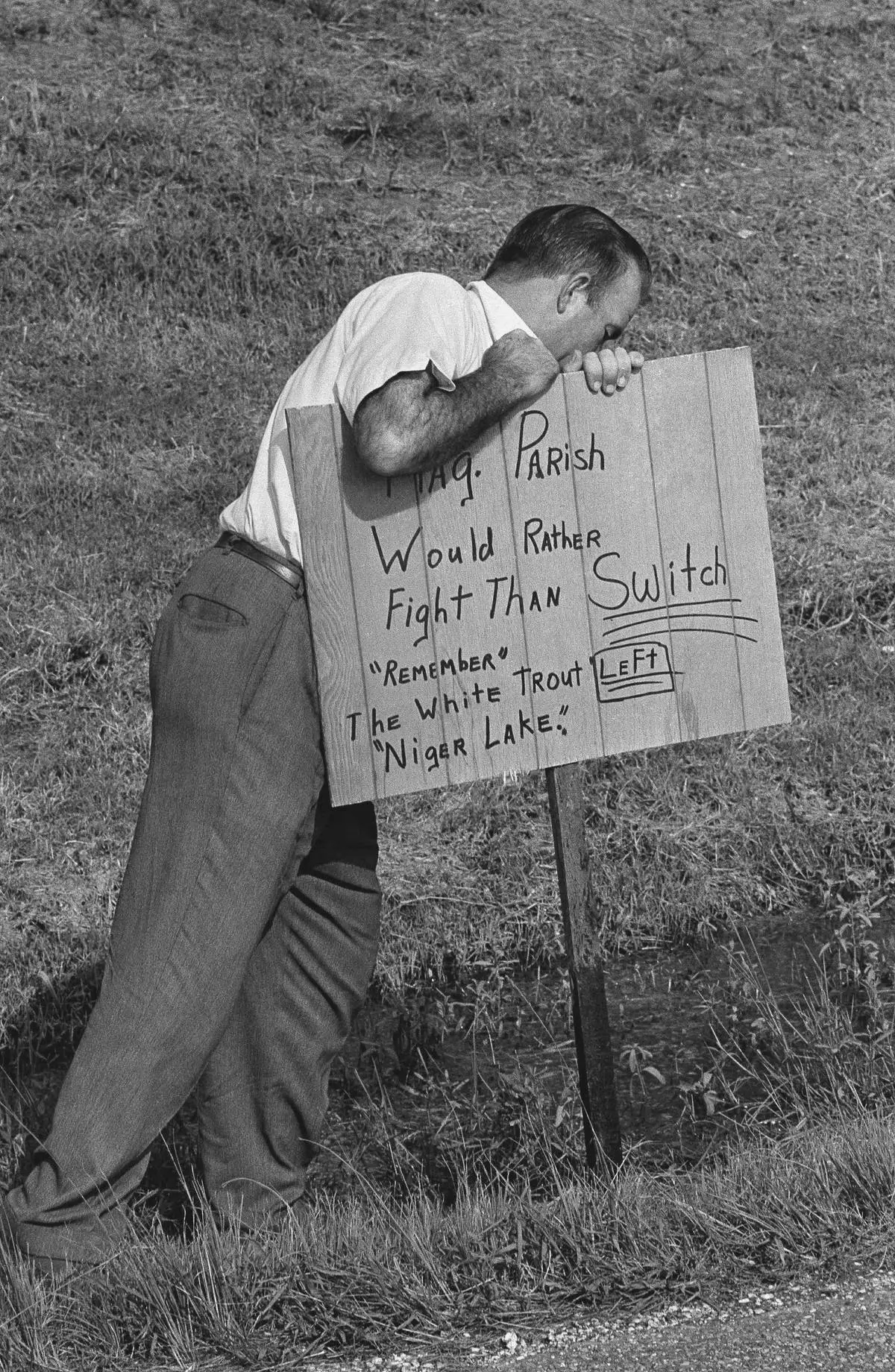

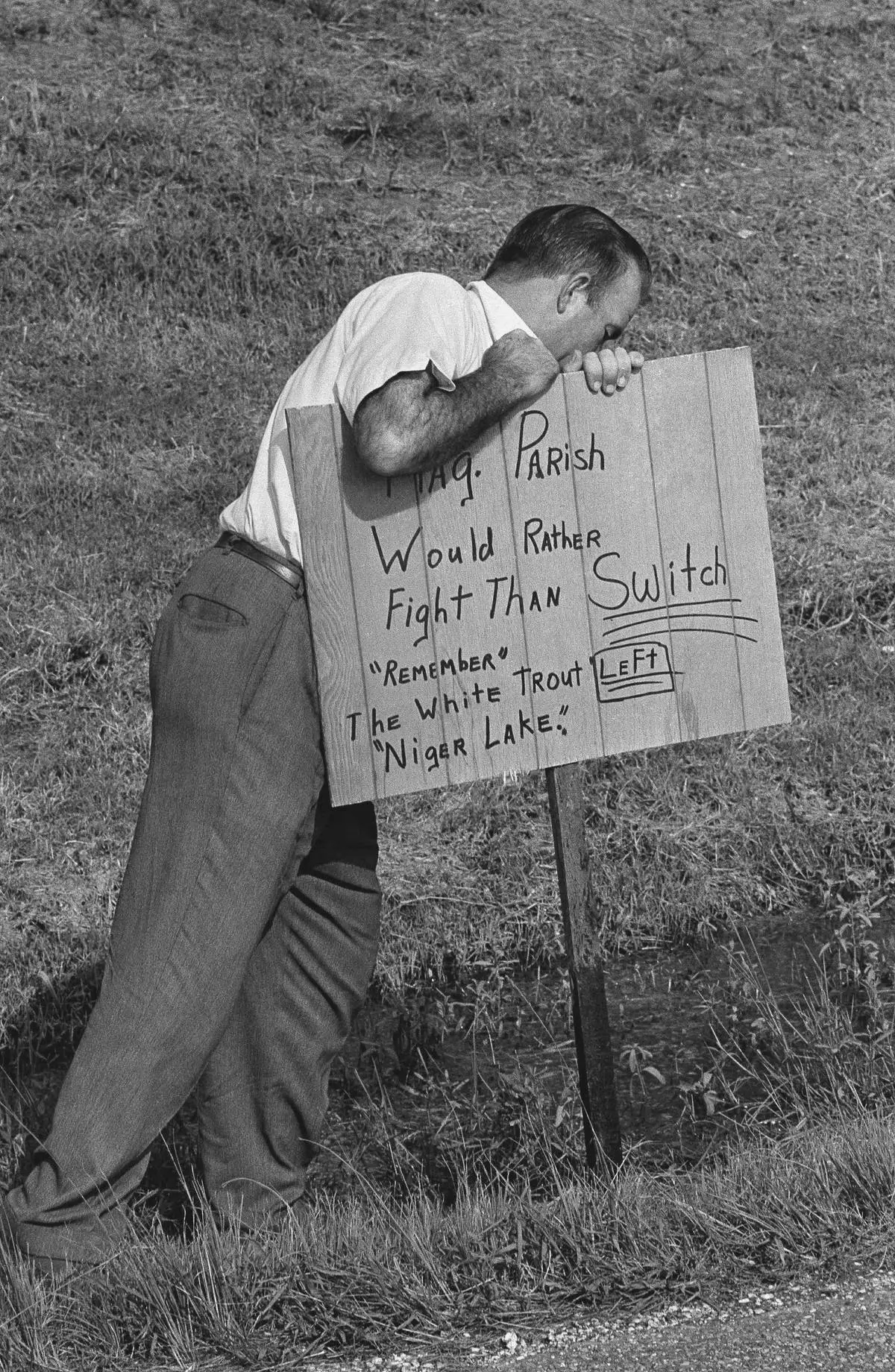

FILE - A man plants a sign reading outside Woodlawn High School in Pointe a la Hache, Louisiana on Sept. 1, 1966 where five African Americans applied for registration for the first time in parish history. (AP Photo/Jack Thornell, file)

FILE - A group of African American students, left, enter the Boothville-Venice School in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana on Sept. 12, 1966 as a group of white mothers wait at the entrance of the school. (AP Photo/Jack Thornell, file)