NEW YORK (AP) — Bulls, bears and dead cats are lurking in the background of President Donald Trump's trade war. As the effects of the administration's latest tariffs unfold, news consumers may confront unfamiliar terms related to investments or financial markets. Here is a guide to some of the most common words:

A bear market is a term used by Wall Street when an index such as the S&P 500 or the Dow Jones Industrial Average has fallen 20% or more from a recent high for a sustained period of time.

Why use a bear to refer to a market slump? Bears hibernate, so they represent a stock market in retreat. In contrast, Wall Street’s nickname for a surging market is a bull market, because bulls charge.

When stocks rebound briefly in a moment of free fall or uncertainty, it's known as a “dead cat bounce." That's from the notion that even a dead cat will bounce when it falls from a great enough height. The market recovery tends to be temporary and brief, and the downturn tends to resume.

Capitulation refers to the point when investors give up on the idea of recouping their losses and sell, often out of fear and intolerance of falling prices. This tends to happen during times of low confidence and high uncertainty and volatility.

Capitulation can sometimes indicate the bottom of a market, but it's easier to identify in retrospect.

A recession is a time when the economy shrinks and unemployment rises.

Recessions are officially declared by the obscure-sounding National Bureau of Economic Research, a group of economists who consider factors such as hiring trends, income levels, spending, retail sales and factory output. The bureau's Business Cycle Dating Committee defines a recession as “a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and lasts more than a few months.”

The organization typically does not declare a recession until well after one has begun, sometimes as long as a year later.

In the days before Trump’s most recent tariffs took effect, economists at Goldman Sachs raised their assessment of the odds the U.S. will experience a recession from 35% to as high as 65%, but the analysts rescinded that forecast Wednesday after his administration announced a 90-day pause on most of the levees.

"Buying the dip” refers to purchasing a stock or buying into the market right after it has lost value, at a discount. The phrase is commonly used by retail investors. Unfortunately, it's all but impossible to time the market, to know where the bottom will be or how long a recovery will take.

The 10-year Treasury bond yield is the interest rate the U.S. government pays to borrow money for a decade. It's a key indicator of investor sentiment and economic conditions, and it helps set prices for all kinds of other loans and investments. The yield influences borrowing costs and signals expectations about inflation and economic growth.

Historically, Treasury bonds are considered one of the world's safest assets. That means investors often buy them when there's uncertainty in the market, which tends to lower the yield. Prices for the 10-year bonds tend to fall when confidence is high (and people buy assets perceived as riskier), which causes yields to rise.

In recent days, however, investors have sold Treasury bonds, which has sent the benchmark 10-year yield up. That could point to a lack of consumer confidence in Treasury bonds themselves, or any number of other factors.

Associated Press writers Stan Choe, Alex Veiga and Chris Rugaber contributed to this report.

The Associated Press receives support from Charles Schwab Foundation for educational and explanatory reporting to improve financial literacy. The independent foundation is separate from Charles Schwab and Co. Inc. The AP is solely responsible for its journalism.

Pedestrians walk past a Wall Street sign on the sidewalk near the New York Stock Exchange in New York, Wednesday, April 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

An electronic display show financial information on the floor at the New York Stock Exchange in New York, Tuesday, April 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

The New York Stock Exchange is seen in New York, Tuesday, April 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

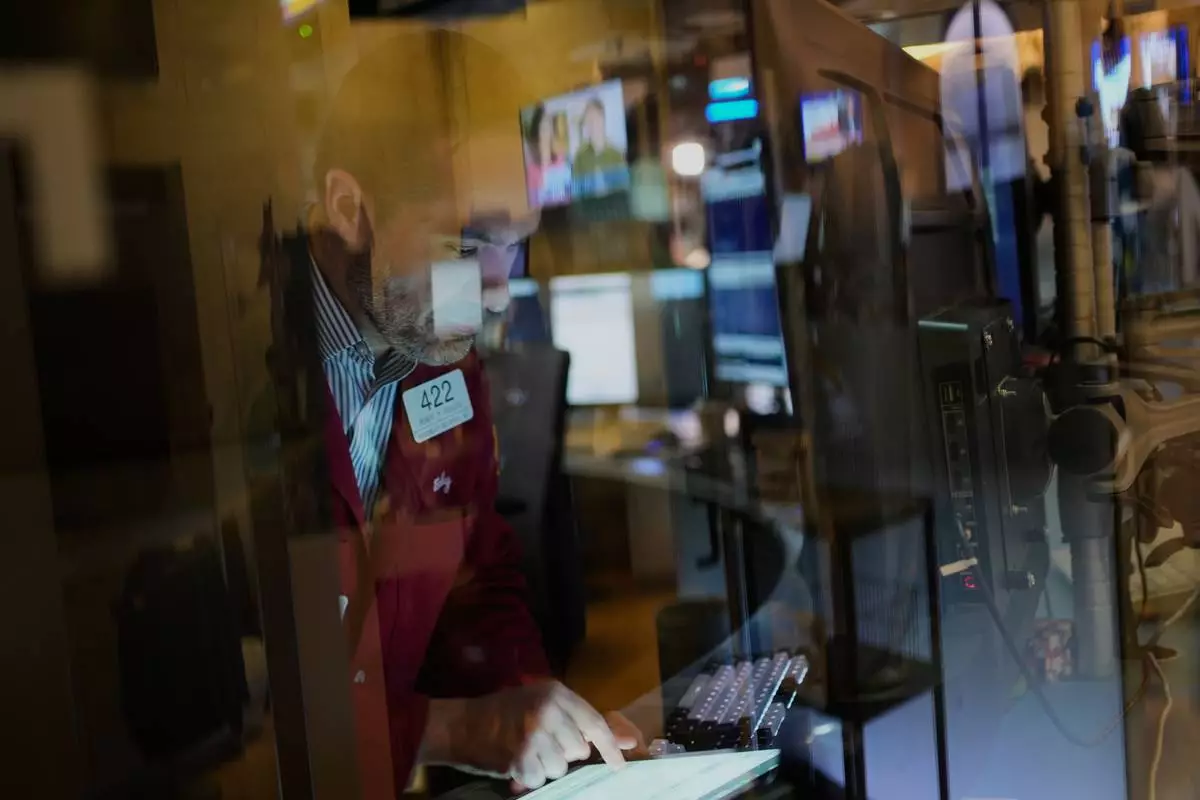

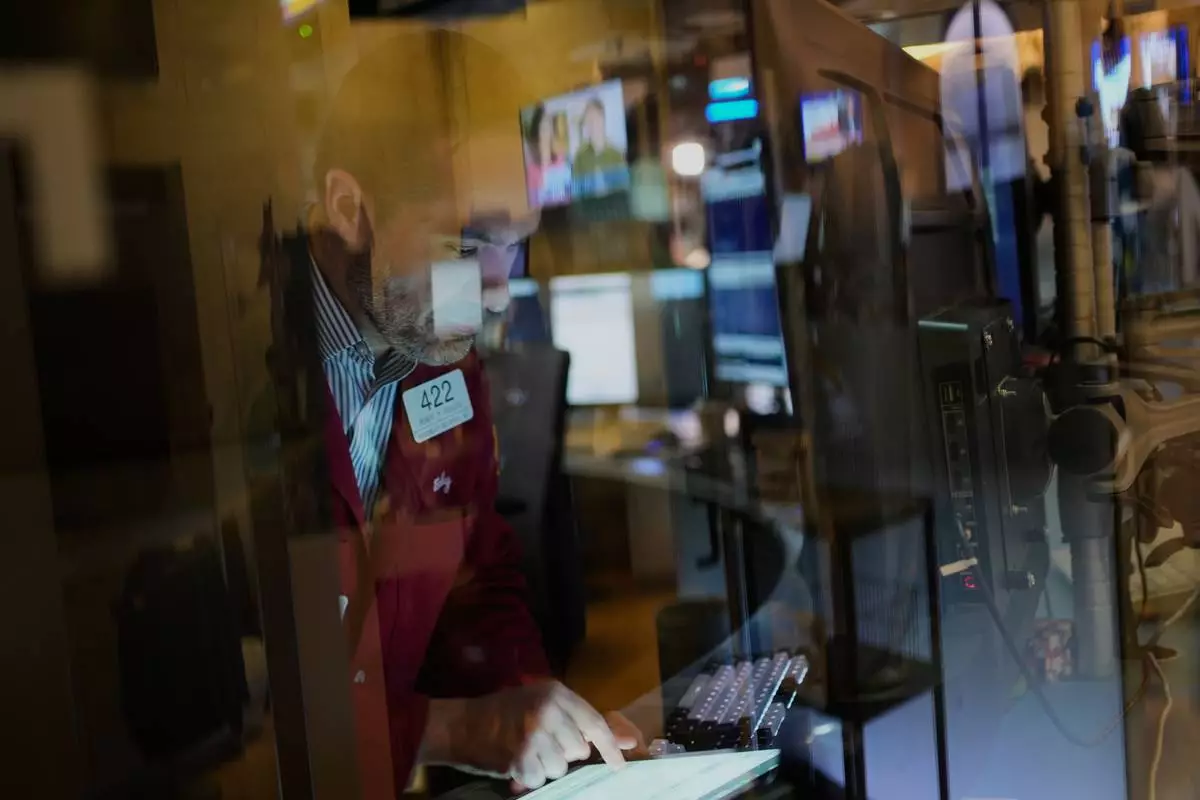

Traders work on the floor at the New York Stock Exchange in New York, Wednesday, April 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

NEW YORK (AP) — Uncertainty continues to hang over the latest round of financial results and forecasts for companies both big and small as they try to navigate a global trade system severely shaken by a shift in U.S. policy.

Roughly half of the companies in the S&P 500 have reported their latest quarterly financial results, but the focus has been on how they will adjust to tariffs and any change in consumers’ behavior. Here’s a look a what companies are saying about tariffs and the potential impact:

General Motors expects tariffs to inflict between $4 billion and $5 billion in damage to its revenue for the year.

Auto companies like General Motors have operations spread out throughout North America, with auto parts and assembly steps often crossing multiple borders before a car is produced.

The company said that it expects full-year adjusted earnings before interest and taxes in a range of $10 billion to $12.5 billion. That’s down from a previous range of $13.7 billion to $15.7 billion.

President Donald Trump signed executive orders Tuesday to relax some of his 25% tariffs on automobiles and auto parts.

Harley-Davidson withdrew its financial forecast for the year because of uncertainty over tariffs and the economy.

The iconic motorcycle maker is facing an impact from 25% tariffs on steel and aluminum imports, along with other broader tariffs. It said it is focusing on productivity measures, supply chain management and cost controls to help deal with the impact from tariffs. The company gets just under 70% of its revenue from within the U.S., according to FactSet. That leaves a large chunk of its revenue exposed to retaliatory tariffs from other nations.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce is asking the Trump administration for some relief on tariffs, particularly for small businesses that are the most affected.

The group is the world’s largest business federation and represents 3 million businesses of all sizes. In a letter to Secretary of the Treasury Scott Bessent, Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick and U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer, U.S. Chamber CEO Suzanne Clark said the group agrees with many of President Trump’s policy goals, but said tariffs take time to work, and in the interim small businesses are being endangered by higher costs and a disrupted supply chain.

The Chamber is calling for automatic exclusions for any small business importer. It also wants to establish a process for businesses to apply for exclusions if they can show American employment is at risk from the tariffs, and asking for exclusions for all products that cannot be produced in the United States or are not readily available.

“Whether it is coffee, bananas, cocoa, minerals or numerous other products, the reality is certain things just can’t be produced in the United States,” said Clark. Providing some exclusions could help “stave off a recession,” she added.

Hershey reaffirmed its financial forecasts for the year, which include assessments for tariff expenses as they currently stand.

The chocolate maker estimates the current tariff expenses to range from about $15 million to $20 million in the second quarter. Hershey and other chocolate makers are already dealing with cocoa supply issues that have helped push prices higher. More than 70% of the global cocoa supply comes from West Africa and the region has been dealing with stressed and damaged crops for years.

Church & Dwight slashed its financial forecasts for the year as it faces the impact from tariffs and a potential slowdown in consumer spending.

The maker of Arm & Hammer and other household and personal care products now expects earnings to range from flat to 2% growth. It previously forecast earnings growth of up to 8%.

It estimated that its tariff exposure over the next 12 months is about $190 million. The company hopes to reduce that exposure by up to 80% with several measures, including no longer sourcing Waterpik flossers from China for the U.S. market. It will also potentially shut down or sell some of its brands.

Becton Dickinson trimmed its earnings forecast for the year to account for a tariffs currently in effect.

The medical device maker and supplies company expects earnings between $14.06 and $14.34 per share and that includes a 25 cents-per-share tariff impact. But the company has not estimated the potential costs of any delayed or threatened tariffs.

“Obviously, the situation remains extremely fluid,” said Chief Financial Officer Christopher DelOrefice, in a conference call with analysts. “We will see how the next few months play out as it relates to further tariff rates.”

McDonald’s, like other fast-food operations and restaurants, is dealing with the economic uncertainty fueled by the tariffs.

The company reported that store traffic fell further than expected during the first quarter. Sales at locations open at least a year in the U.S. slumped 3.6%, marking the biggest decline for the company since 2020, when a pandemic shuttered stores and restaurants.

“We believe McDonald’s can weather these difficult conditions better than most,” said CEO Chris Kempczinski, in a conference call with investors. “However, we’re not immune to the volatility in the industry or the pressures that our consumers are facing.”

AP writers Michelle Chapman, Mae Anderson and Dee-Ann Durbin contributed to this report.

FILE - The General Motors logo is displayed at the General Motors Detroit-Hamtramck Assembly plant in Hamtramck, Mich., Jan. 27, 2020. (AP Photo/Paul Sancya, File)