SAN JUAN, Puerto Rico (AP) — Crews scrambled to restore power to Puerto Rico on Thursday after a blackout hit the entire island the previous day, affecting the main international airport, hospitals and hotels filled with Easter vacationers.

The outage that began around midday Wednesday left 1.4 million customers without electricity and more than 400,000 without water. More than 958,000 customers, or 65%, had power back by Thursday night, while 89% of customers had water restored. Officials expected 90% of customers to have power back within 48 to 72 hours after the outage, although 200,000 clients were left without power again on Thursday afternoon when one power plant failed twice.

Click to Gallery

A man uses a plastic plate to fan the flames of a makeshift charcoal grill outside his home during a blackout in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Thursday, April 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Alejandro Granadillo)

Nurys Perez, owner of Nurys Salon, styles a client's hair on the sidewalk outside her shop during a blackout in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Thursday, April 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Alejandro Granadillo)

Drivers fill up fuel containers at a gas station during an island-wide blackout in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Wednesday, April 16, 2025. (AP Photo/Alejandro Granadillo)

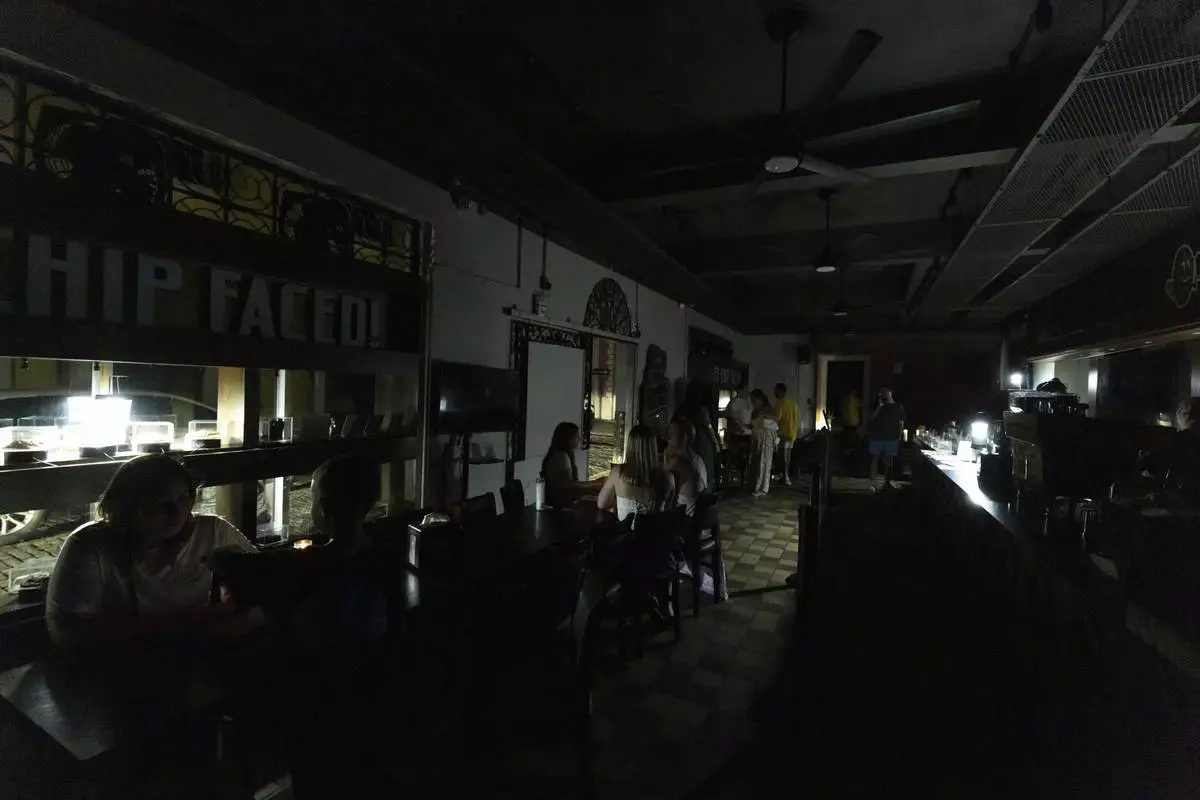

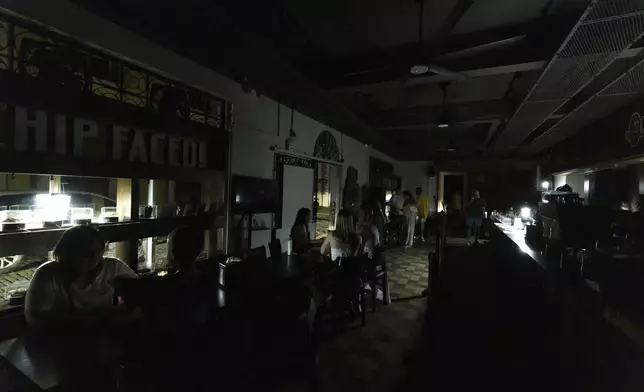

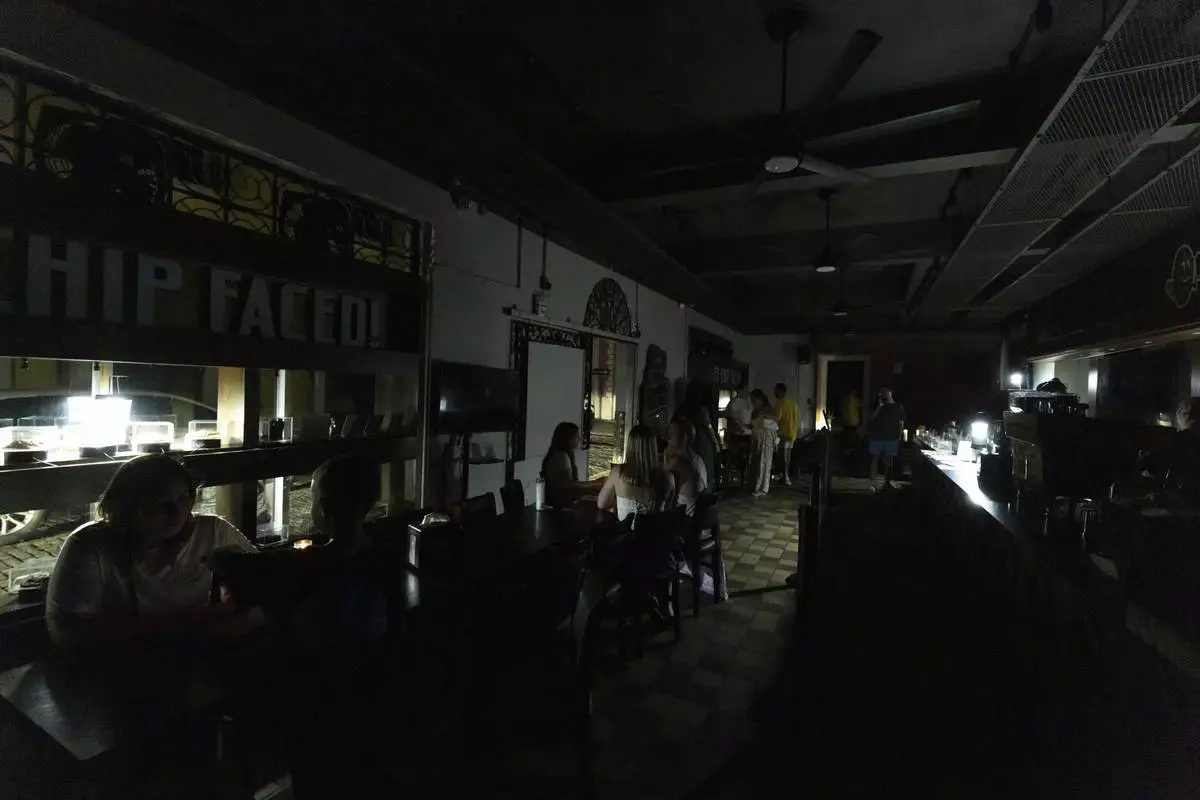

Customers sit inside a restaurant lit by battery-powered lanterns during an island-wide power outage, in Old San Juan, Puerto Rico, Wednesday, April 16, 2025. (AP Photo/Alejandro Granadillo)

Vehicles navigate a dark street in Old San Juan, Puerto Rico, during an island-wide blackout, Wednesday, April 16, 2025. (AP Photo/Alejandro Granadillo)

A local fills fuel containers at a gas station in San Juan, Puerto Rico, during an island-wide blackout, Wednesday, April 16, 2025. (AP Photo/Alejandro Granadillo)

A gas station employee directs traffic as cars line up for fuel during an island-wide blackout in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Wednesday, April 16, 2025. (AP Photo/Alejandro Granadillo)

Headlights illuminate cobblestone streets in Old San Juan, Puerto Rico, during an island-wide blackout, Wednesday, April 16, 2025. (AP Photo/Alejandro Granadillo)

“We are still in a precarious situation. This is old, fragile equipment," said Gov. Jenniffer González, who cut her weeklong vacation short and returned to Puerto Rico on Wednesday evening.

She said it would take at least three days to have preliminary information on what might have caused the blackout, which snarled traffic, forced hundreds of businesses to close and left those unable to afford generators scrambling to buy ice and candles.

“This is a shame for the people of Puerto Rico that we have a problem of this magnitude,” the governor said.

González warned that the boiler of one power plant was not functioning and would take one week to repair, which could affect power generation next week, when people return from vacation.

It’s the second massive blackout to hit Puerto Rico in less than four months. The previous one happened on New Year’s Eve.

“Why on holidays?” griped José Luis Richardson, who did not have a generator and kept cool by splashing water on himself every couple of hours.

The roar of generators and smell of fumes filled the air as a growing number of Puerto Ricans renewed calls for the government to cancel the contracts with Luma Energy, which oversees the transmission and distribution of power, and Genera PR, which oversees power generation.

González promised to heed those calls.

“That is not under doubt or question,” she said, but added that it’s not a quick process. “It is unacceptable that we have failures of this kind.”

González said a major outage, like the latest one, causes an estimated $215 million revenue loss daily.

Ramón C. Barquín III, president of the United Retail Center, a nonprofit that represents small- and medium-sized businesses, warned that ongoing outages would spook potential investors at a time when Puerto Rico urgently needs economic development.

“We cannot continue to repeat this cycle of blackouts without taking concrete measures to strengthen our energy infrastructure,” he said.

Many also were concerned about Puerto Rico’s elderly population, with the mayor of Canóvanas deploying brigades to visit the bedridden and those who depend on electronic medical equipment.

Meanwhile, the mayor of Vega Alta opened a center to provide power to those with lifesaving medical equipment.

Wednesday night was difficult for many, including 62-year-old Santos Bones Burgos.

“I spent it on the balcony,” he said, adding that he was trying to get some fresh air.

At some point, he fell asleep and recalled waking up at 5 a.m. to a neighbor yelling, “The power is back!”

Among those unable to sleep was Dorca Navarrete, a 50-year-old house cleaner who said it was too hot. “Last night was horrible,” she said. "I woke up with a headache.”

When she opened her eyes, she saw light and thought it couldn't possibly be the sun at that hour. Then a smile spread across her face when she realized it was from the light she had left on in a room the day before.

It was not immediately clear what caused the shutdown, the latest in a string of major blackouts on the island in recent years.

Officials are looking into whether several breakers failed to open or exploded. González said.

Another possibility is that overgrown vegetation affected the grid, which, if true, should not have happened, said Josué Colón, the island’s energy czar and former executive director of Puerto Rico’s Electric Power Authority.

He noted that the authority flew daily to check on certain lines, something he said Luma should be doing.

Colón said Luma also needs to explain why all the generators shut down after there was a failure in the transmission system, when only one was supposed to go into protective mode.

Pedro Meléndez, a Luma engineer, said an investigation is ongoing. He said in a news conference Thursday that the line where the failure occurred was inspected last week as part of regular air patrols to check on more than 2,500 miles worth of transmission lines across the island.

“No imminent risk was identified,” he said.

Daniel Hernández, vice president of operations at Genera PR, said Wednesday that a disturbance hit the transmission system shortly after noon, a time when the grid is vulnerable because there are few machines regulating frequency at that hour.

Puerto Rico has struggled with chronic outages since September 2017, when Hurricane Maria pummeled the island as a powerful Category 4 storm, razing a power grid that crews are still struggling to rebuild.

The grid already had been deteriorating as a result of decades of a lack of maintenance and investment under the state's Electric Power Authority, which is struggling to restructure $9 billion in debt.

On Jan. 9, Puerto Rico's representative in Congress, Pablo José Hernández, joined by legislators including Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, sent a letter to U.S. Energy Secretary Chris Wright calling for the release of federal funds slated for the installation of rooftop solar and battery storage in Puerto Rico. The money is meant to help those whose disabilities or medical conditions require a power connection.

Puerto Rico's governor also has repeatedly called for those funds to be released.

Follow AP’s coverage of Latin America and the Caribbean at https://apnews.com/hub/latin-america

A man uses a plastic plate to fan the flames of a makeshift charcoal grill outside his home during a blackout in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Thursday, April 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Alejandro Granadillo)

Nurys Perez, owner of Nurys Salon, styles a client's hair on the sidewalk outside her shop during a blackout in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Thursday, April 17, 2025. (AP Photo/Alejandro Granadillo)

Drivers fill up fuel containers at a gas station during an island-wide blackout in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Wednesday, April 16, 2025. (AP Photo/Alejandro Granadillo)

Customers sit inside a restaurant lit by battery-powered lanterns during an island-wide power outage, in Old San Juan, Puerto Rico, Wednesday, April 16, 2025. (AP Photo/Alejandro Granadillo)

Vehicles navigate a dark street in Old San Juan, Puerto Rico, during an island-wide blackout, Wednesday, April 16, 2025. (AP Photo/Alejandro Granadillo)

A local fills fuel containers at a gas station in San Juan, Puerto Rico, during an island-wide blackout, Wednesday, April 16, 2025. (AP Photo/Alejandro Granadillo)

A gas station employee directs traffic as cars line up for fuel during an island-wide blackout in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Wednesday, April 16, 2025. (AP Photo/Alejandro Granadillo)

Headlights illuminate cobblestone streets in Old San Juan, Puerto Rico, during an island-wide blackout, Wednesday, April 16, 2025. (AP Photo/Alejandro Granadillo)

CAXIUANA NATIONAL FOREST, Brazil (AP) — Deep in silence, as if under a spell, children watch intently as Bacuri, a young Amazonian manatee, glides around a small plastic pool. When he surfaces for air, some of them exchange wide smiles. The soft rustle of rainforest leaves punctuated by bird song adds to the magic of the moment.

The children from riverside communities traveled for hours by boat just to meet Bacuri at the field station of the Emilio Goeldi Museum, Brazil’s oldest research institute in the Amazon. Despite their endangered status, manatees are still hunted and their meat illegally sold, and they are increasingly threatened by climate change. Environmentalists hope that by engaging local communities, Bacuri and others like him will be spared.

The Amazonian manatee is the region’s largest mammal but is rarely seen, much less up close. The reasons for this are twofold: The manatee has acute hearing and will vanish into the murky water at the slightest sound; and its population has dwindled after being overhunted for hundreds of years, mostly for its tough hides that were exported to Europe and Central America.

To help the manatee population recover, several institutions are rescuing orphaned manatee calves, rehabilitating them and reintroducing them to the wild.

Bacuri weighed just 22 pounds (10 kilograms) — a fraction of the more than 900 pounds (400 kilograms) of an adult manatee — when he was rescued and taken to the museum's research center in the federally protected Caxiuana National Forest. He was named after the local community that found him. Two years and several thousand milk bottles later, Bacuri has grown to about 130 pounds (60 kilos).

Three institutions are responsible for his care. The Goeldi Museum provides facilities and educates nearby communities. The federal Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation assigns two staffers for 15-day shifts to feed Bacuri three bottles of milk a day as well as chopped beets and carrots, and clean the pool every 48 hours. The nonprofit Instituto Bicho d'Agua— meaning institute of water animals in Portuguese — oversees veterinary care, dietary planning and caregiver training.

During their visit, the children learn that female manatees are pregnant for about a year then nurse their young for two more, feeding them from nipples behind their front flippers — the manatee equivalent of armpits. This long reproductive cycle is one reason the manatee population has not recovered from the commercial hunting that persisted until the mid-20th century.

They also learn the species is endangered and that they are the ones who must protect it.

“You are the main guardians,” biologist Tatyanna Mariúcha, head of the scientific base, tells the children, who spend the rest of the day drawing and making Play-Doh models of Bacuri.

With its auditorium, dormitories, observation towers, cafeteria and laboratories, the research station — two hours by speedboat from Portel, the nearest city — stands in stark contrast to nearby communities comprising clusters of wooden houses on stilts where families rely on cassava farming, fishing and harvesting açaí berries. School field trips and community outreach aim to narrow the gap.

“Caxiuana is their home,” Mariúcha told The Associated Press. “We can’t just come here and do things without their consent.”

Local knowledge will play a key role when Bacuri is finally released. He is the only manatee calf under care at Caxiuana. Once he has fully transitioned to a plant-based diet, he’ll spend time in a river enclosure before his release. That site will be selected based on where residents say wild manatees feed and pass through.

If all goes as planned, Bacuri will be the first released in the Caxiuana area. Two other calves rescued in poor health died in captivity, a sadly common outcome.

While subsistence hunting isn’t a major threat to the species, some fishermen still sell manatee meat illegally in nearby towns. Brazil banned hunting of all wild animals in 1967, with two exceptions: Indigenous peoples are allowed to hunt, and others can kill a wild animal to satisfy the hunger of the hunter or his family.

The threat of hunters has become harder to manage due to climate change, said Miriam Marmontel, a senior researcher at the Mamirauá Institute for Sustainable Development, hundreds of miles (kilometers) upstream along the Amazon River.

Dozens of dolphins died near Mamiraua in 2023, likely due to soaring water temperatures during a historic drought. Manatees avoided mass mortality then because they typically inhabit deep pools during the dry season, but recent droughts have dramatically reduced the water level, making manatees more vulnerable to poachers.

“As climate change accelerates, manatees may begin to suffer from heat stress too,” Marmontel said. “They also have a thermal limit, and eventually it may be crossed.”

That’s why reintroduction efforts are so important.

Around 60 rescued manatees are being cared for across the state of Para, where Caxiuana is located. Bicho d’Agua is caring for four in partnership with the Federal University of Para and Brazil's environmental agency. One of the four, named Coral, was found near Óbidos and airlifted 620 miles (1,000 kilometers) to the institute's facility in Castanhal. She arrived dehydrated and with severe skin burns, likely from sun exposure.

“The population has declined so much that every hunted animal impacts the species,” Renata Emin, president of Bicho d’Agua, told AP. “That’s why any effort matters, not just because one individual may return to the wild and help rebuild the population but because of the community and government engagement it inspires.”

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Maria, a rescued manatee, swims in a pool at the Bicho d'Agua project facilities in Castanhal, Brazil, Sunday, March 23, 2025. (AP Photo/Jorge Saenz)

Coral, a rescued manatee, is fed while in a pool at the Bicho d'Agua project facilities in Castanhal, Brazil on Sunday, March 23, 2025. (AP Photo/Jorge Saenz)

Coral, a rescued manatee, swims in a pool at the Bicho d'Agua project facilities in Castanhal, Brazil, Sunday, March 23, 2025. (AP Photo/Jorge Saenz)

Coral, a rescued manatee, sleeps belly up in a pool at Bicho d'Agua project facilities in Castanhal, Brazil, Sunday, March 23, 2025. (AP Photo/Jorge Saenz)

Coral, a rescued manatee, receives healing cream from an assistant at a pool at Bicho d'Agua project facilities in Castanhal, Brazil, Sunday, March 23, 2025. (AP Photo/Jorge Saenz)

Workers clean a pool near Bacuri, a rescued manatee, at the Emilio Goeldi Museum's scientific station in Para state, Brazil, Thursday, March 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Jorge Saenz)

Children make manatee models out of Play-Doh during a trip to Emilio Goeldi Museum's scientific station in Para state, Brazil, Friday, March 21, 2025. (AP Photo/Jorge Saenz)

Bacuri, a rescued manatee, swims as children observe in the Emilio Goeldi Museum's scientific base at Caxiuana National Forest in Para state, Brazil, Friday, March 21, 2025. (AP Photo/Jorge Saenz)

A girl embraces biologist Tatyanna Mariúcha, head of the Emilio Goeldi Museum's scientific base, as children arrive at the station in the Caxiuana National Forest in Para state, Brazil, Friday, March 21, 2025. (AP Photo/Jorge Saenz)

The Curua River crosses the Caxiuana National Forest with Emilio Goeldi Museum's scientific station at bottom in Para state, Brazil, Saturday, March 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Jorge Saenz)

Children arrive at the Emilio Goeldi Museum's scientific station in the Caxiuana National Forest in Para state, Brazil, Friday, March 21, 2025. (AP Photo/Jorge Saenz)

Bacuri, a rescued manatee, breathes while swimming in a pool at the Emilio Goeldi Museum's scientific station in the Caxiuana National Forest in Para state, Brazil, Thursday, March 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Jorge Saenz)