WASHINGTON (AP) — The Trump administration’s claim that it can't do anything to free Kilmar Abrego Garcia from an El Salvador prison and return him to the U.S. “should be shocking,” a federal appeals court said Thursday in a blistering order that ratchets up the escalating conflict between the government's executive and judicial branches.

A three-judge panel from the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals unanimously refused to suspend a judge's decision to order sworn testimony by Trump administration officials to determine if they complied with her instruction to facilitate Abrego Garcia's return.

Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III, who was nominated by Republican President Ronald Reagan, wrote that he and his two colleagues “cling to the hope that it is not naïve to believe our good brethren in the Executive Branch perceive the rule of law as vital to the American ethos.”

“This case presents their unique chance to vindicate that value and to summon the best that is within us while there is still time,” Wilkinson wrote.

The seven-page order amounts to an extraordinary condemnation of the administration’s position in Abrego Garcia’s case and also an ominous warning of the dangers of an escalating conflict between the judiciary and executive branches the court said threatens to “diminish both.” It says the judiciary will be hurt by the “constant intimations of its illegitimacy” while the executive branch “will lose much from a public perception of its lawlessness.”

When asked by reporters Thursday afternoon if he believed Abrego Garcia was entitled to due process, President Donald Trump ducked the question.

“I have to refer, again, to the lawyers,” he said in the Oval Office. “I have to do what they ask me to do.”

The president added: “I had heard that there were a lot of things about a certain gentleman — perhaps it was that gentleman — that would make that case be a case that’s easily winnable on appeal. So we’ll just have to see. I’m gonna have to respond to the lawyers.”

The Justice Department didn’t immediately comment on the decision. In a brief accompanying their appeal, government lawyers argued that courts do not have the authority to “press-gang the President or his agents into taking any particular act of diplomacy.”

“Yet here, a single district court has inserted itself into the foreign policy of the United States and has tried to dictate it from the bench,” they wrote.

The panel said the Republican president's government is “asserting a right to stash away residents of this country in foreign prisons without the semblance of due process that is the foundation of our constitutional order.”

“Further, it claims in essence that because it has rid itself of custody that there is nothing that can be done. This should be shocking not only to judges, but to the intuitive sense of liberty that Americans far removed from courthouses still hold dear,” Wilkinson wrote.

Earlier this month, the Supreme Court said the Trump administration must work to bring back Abrego Garcia. An earlier order by U.S. District Judge Paula Xinis “properly requires the Government to ‘facilitate’ Abrego Garcia’s release from custody in El Salvador and to ensure that his case is handled as it would have been had he not been improperly sent to El Salvador,” the high court said in an unsigned order with no noted dissents.

The Justice Department appealed after Xinis on Tuesday ordered sworn testimony by at least four officials who work for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the Department of Homeland Security and the State Department.

The 4th Circuit panel denied the government's request for a stay of Xinis' order while they appeal.

“The relief the government is requesting is both extraordinary and premature," the opinion says. "While we fully respect the Executive’s robust assertion of its Article II powers, we shall not micromanage the efforts of a fine district judge attempting to implement the Supreme Court’s recent decision.”

Wilkinson, the opinion's author, was regarded as a contender for the Supreme Court seat that was ultimately filled by Chief Justice John Roberts in 2005. Wilkinson’s conservative pedigree may complicate White House efforts to credibly assail him as a left-leaning jurist bent on thwarting the Trump administration’s agenda for political purposes, a fallback line of attack when judicial decisions run counter to the president’s wishes.

Joining Wilkinson in the ruling were judges Stephanie Thacker, who was nominated by Democratic President Barack Obama, and Robert Bruce King, who was nominated by Democratic President Bill Clinton.

White House officials claim they lack the authority to bring back the Salvadoran national from his native country. Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele also said Monday that he would not return Abrego Garcia, likening it to smuggling “a terrorist into the United States.”

While initially acknowledging Abrego Garcia was mistakenly deported, the administration has dug in its heels in recent days, describing him as a “terrorist” even though he was never criminally charged in the U.S.

Attorney General Pam Bondi said Wednesday that “he is not coming back to our country.”

Maryland Sen. Chris Van Hollen met with Abrego Garcia in El Salvador on Thursday. Van Hollen posted a photo of the meeting on X, but he did not provide an update on Abrego Garcia's status. Bukele also posted images of the meeting, saying, “Now that he’s been confirmed healthy, he gets the honor of staying in El Salvador’s custody.”

Administration officials have conceded that Abrego Garcia shouldn't have been sent to El Salvador, but they have insisted that he was a member of the MS-13 gang. Abrego Garcia's lawyers say there is no evidence linking him to MS-13 or any other gang.

The appeals court panel concluded that Abrego Garcia deserves due process, even if the government can connect him to a gang.

“If the government is confident of its position, it should be assured that position will prevail in proceedings to terminate the withholding of removal order,” the opinion says.

Xinis also was skeptical of assertions by White House officials and Bukele that they were unable to bring back Abrego Garcia. She described their statements as “two very misguided ships passing in the night.”

“The Supreme Court has spoken,” Xinis said Tuesday.

Associated Press writer Will Weissert contributed reporting.

Jennifer Vasquez Sura, the wife of Kilmar Abrego Garcia of Maryland, who was mistakenly deported to El Salvador, speaks during a news conference at CASA's Multicultural Center in Hyattsville, Md., Friday, April 4, 2025. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana)

FILE - Jennifer Vasquez Sura, the wife of Kilmar Abrego Garcia of Maryland, who was mistakenly deported to El Salvador, speaks during a news conference at CASA's Multicultural Center in Hyattsville, Md., April 4, 2025. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana, file)

VATICAN CITY (AP) — “Conclave” the film may have introduced moviegoers to the spectacular ritual and drama of a modern conclave, but the periodic voting to elect a new pope has been going on for centuries and created a whole genre of historical trivia.

Here are some facts about conclaves past, derived from historical studies including Miles Pattenden's “Electing the Pope in Early Modern Italy, 1450–1700,” and interviews with experts including Elena Cangiano, an archeologist at Viterbo's Palazzo dei Papi (Palace of the Popes).

In the 13th century, it took almost three years — 1,006 days to be exact — to choose Pope Clement IV's successor, making it the longest conclave in the Catholic Church’s history. It's also where the term conclave comes from — "under lock and key," because the cardinals who were meeting in Viterbo, north of Rome, took so long the town's frustrated citizens locked them in the room.

The secret vote that elected Pope Gregory X lasted from November 1268 to September 1271. It was the first example of a papal election by “compromise,” after a long struggle between supporters of two main geopolitical medieval factions — those faithful to the papacy and those supporting the Holy Roman Empire.

Gregory X was elected only after Viterbo residents tore the roof off the building where the prelates were staying and restricted their meals to bread and water to pressure them to come to a conclusion. Hoping to avoid a repeat, Gregory X decreed in 1274 that cardinals would only get “one meal a day” if the conclave stretched beyond three days, and only “bread, water and wine” if it went beyond eight. That restriction has been dropped.

Before 1274, there were times when a pope was elected the same day as the death of his predecessor. After that, however, the church decided to wait at least 10 days before the first vote. Later that was extended to 15 days to give all cardinals time to get to Rome. The quickest conclave observing the 10-day wait rule appears to have been the 1503 election of Pope Julius II, who was elected in just a few hours, according to Vatican historian Ambrogio Piazzoni. In more recent times, Pope Francis was elected in 2013 on the fifth ballot, Benedict XVI won in 2005 on the fourth and Pope Pius XII won on the third in 1939.

The first conclave held under Michelangelo's frescoed ceiling in the Sistine Chapel was in 1492. Since 1878, the world-renowned chapel has become the venue of all conclaves. “Everything is conducive to an awareness of the presence of God, in whose sight each person will one day be judged,” St. John Paul II wrote in his 1996 document regulating the conclave, “Universi Dominici Gregis.” The cardinals sleep a short distance away in the nearby Domus Santa Marta hotel or a nearby residence.

Most conclaves were held in Rome, with some taking place outside the Vatican walls. Four were held in the Pauline Chapel of the papal residence at the Quirinale Palace, while some 30 others were held in St. John Lateran Basilica, Santa Maria Sopra Minerva or other places in Rome. On 15 occasions they took place outside Rome and the Vatican altogether, including in Viterbo, Perugia, Arezzo and Venice in Italy, and Konstanz, Germany, and Lyon, France.

Between 1378-1417, referred to by historians as the Western Schism, there were rival claimants to the title of pope. The schism produced multiple papal contenders, the so-called antipopes, splitting the Catholic Church for nearly 40 years. The most prominent antipopes during the Western Schism were Clement VII, Benedict XIII, Alexander V, and John XXIII. The schism was ultimately resolved by the Council of Constance in 1417, which led to the election of Martin V, a universally accepted pontiff.

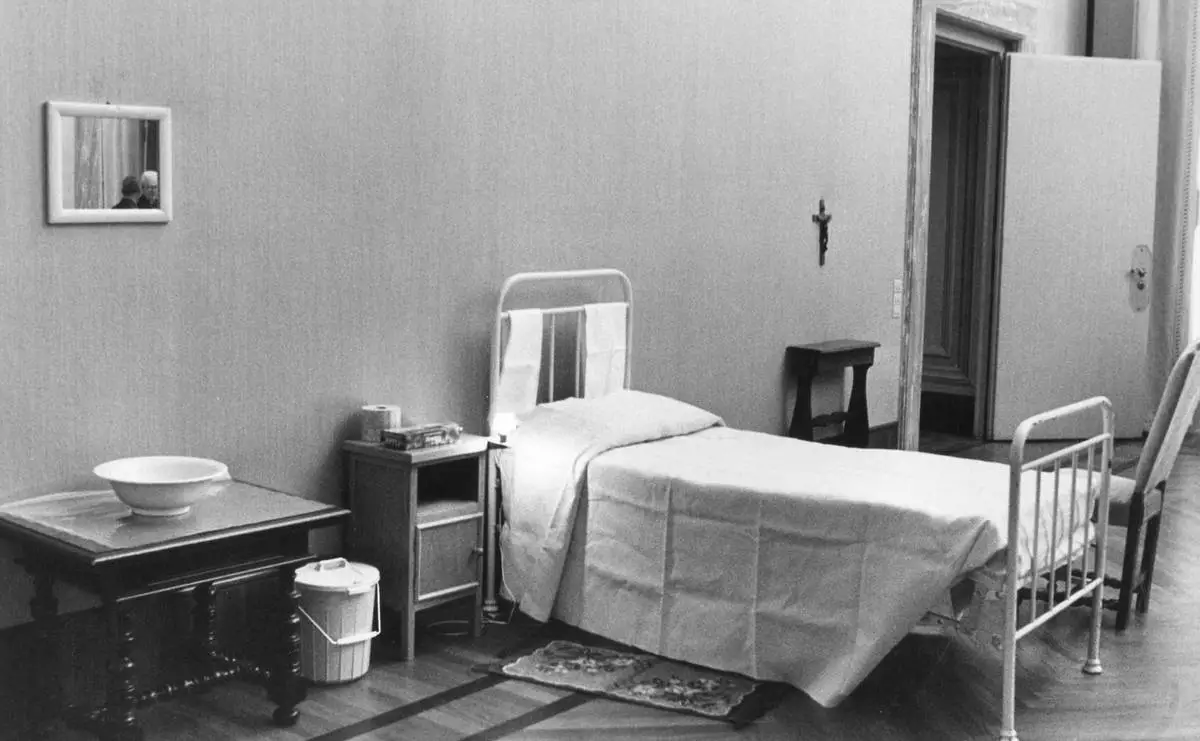

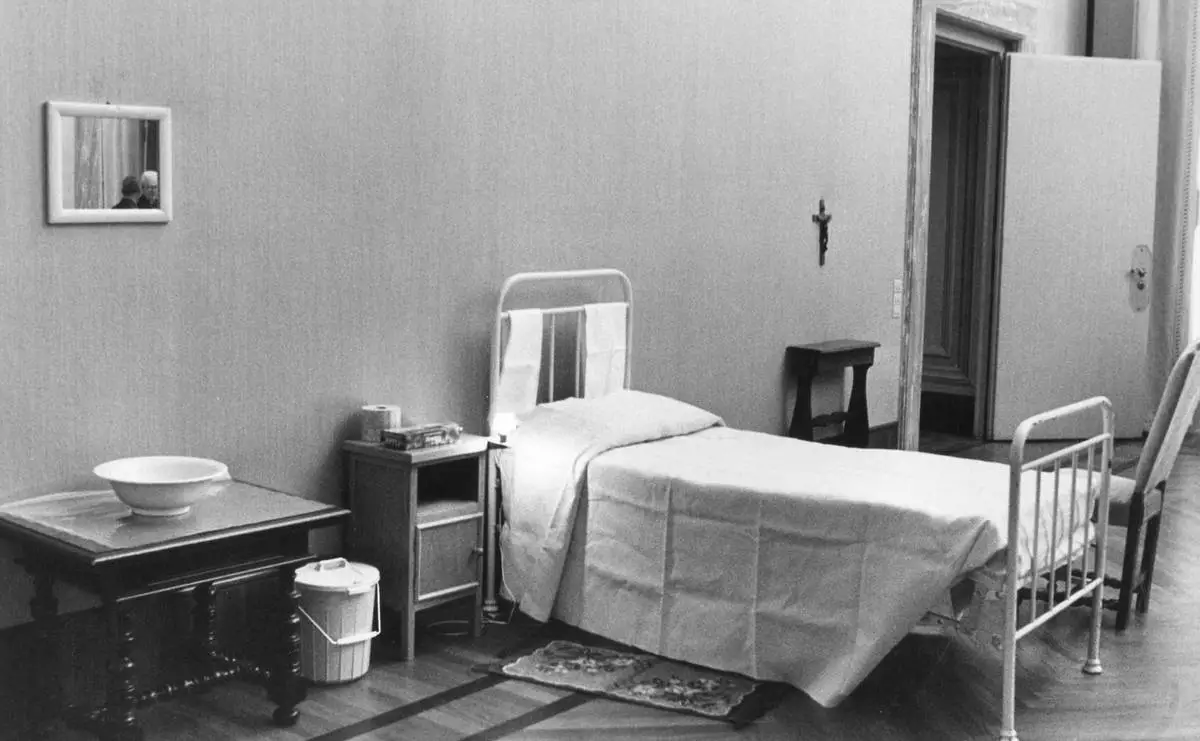

The cloistered nature of the conclave posed another challenge for cardinals: staying healthy. Before the Domus Santa Marta guest house was built in 1996, cardinal electors slept on cots in rooms connected to the Sistine Chapel. Conclaves in the 16th and 17th centuries were described as “disgusting” and “badly smelling,” with concern about disease outbreaks, particularly in summer, according to historian Miles Pattenden. “The cardinals simply had to have a more regular and comfortable way of living because they were old men, many of them with quite advanced disease,” Pattenden wrote. The enclosed space and lack of ventilation further aggravated these issues. Some of the electors left the conclave sick, often seriously.

Initially, papal elections weren’t as secretive, but concerns about political interference soared during the longest conclave in Viterbo. Gregory X decreed that cardinal electors should be locked in seclusion, “cum clave” (with a key), until a new pope was chosen. The purpose was to create a totally secluded environment where the cardinals could focus on their task, guided by God’s will, without any political interference or distractions. Over the centuries, various popes have modified and reinforced the rules surrounding the conclave, emphasizing the importance of secrecy.

Pope John XII was just 18 when he was elected in 955. The oldest popes were Pope Celestine III (elected in 1191) and Celestine V (elected in 1294) who were both nearly 85. Benedict XVI was 78 when he was elected in 2005.

There is no requirement that a pope be a cardinal, but that has been the case for centuries. The last time a pope was elected who wasn’t a cardinal was Urban VI in 1378. He was a monk and archbishop of Bari. While the Italians have had a stranglehold on the papacy over centuries, there have been many exceptions aside from John Paul II (Polish in 1978) and Benedict XVI (German in 2005) and Francis (Argentine in 2013). Alexander VI, elected in 1492, was Spanish; Gregory III, elected in 731, was Syrian; Adrian VI, elected in 1522, was from the Netherlands.

FILE - One of the cells in which a Cardinal will live during the Conclave, at the Vatican, Aug. 23, 1978. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - Cardinals stand in prayer inside the Sistine Chapel after they entered the conclave area for electing the successor of late John Paul I. In the background on the wall Michelangelo's famous fresco "The Last Judgement", in this Oct. 14, 1978 file photo. (AP Photo/Pool, File)

FILE - White smoke is seen billowing out from the chimney of the Sistine Chapel and announcing that a new pope has been elected on Wednesday, March 13, 2013. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia, File)

FILE - Italian Cardinal Giacomo Biffi, center, takes an oath at the beginning of the conclave to elect the next pope in the Sistine Chapel at the Vatican, Monday, April 18, 2005. (AP Photo/Osservatore Romano via AP, File)

FILE - Pope Benedict XVI blesses the faithful as he arrives at St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican, Dec. 16, 2010. (AP Photo/Alessandra Tarantino, File)

FILE - Nuns talk in front of Italian Renaissance artist Michelangelo Buonarroti's Moses statue, part of a funerary monument he designed for Pope Julius II inside San Pietro in Vincoli Basilica in Rome, July 2, 2013. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia, File)

Cardinal Matteo Zuppi, centre, attends a mass on the third of nine days of mourning for late Pope Francis, in St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Monday, April 28, 2025. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini)

FILE - Cardinals walk in procession to the Sistine Chapel at the Vatican, at the beginning of the conclave, April 18, 2005. (Osservatore Romano via AP, File)