VENICE, Italy (AP) — Venice is charging day-trippers to the famed canal city an arrivals tax for the second year starting Friday, a measure aimed at combating the kind of overtourism that put the city's UNESCO World Cultural Heritage status at risk.

A UNESCO body decided against putting Venice on its list of cultural heritage sites deemed in danger after the tax was announced. But opponents of the day-tripper fee say it has done nothing to discourage tourists from visiting Venice even on high-traffic days.

Click to Gallery

Tourists take pictures next Rialto Bridge "Ponte di Rialto" in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

A taxi sails under the Rialto Bridge "Ponte di Rialto" in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Tourists take pictures in San Marco square in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Tourists take a break in San Marco square in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

People walk in San Marco square in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Tourists take pictures on Rialto Bridge "Ponte di Rialto" in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Tourists take pictures on Rialto Bridge "Ponte di Rialto" in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

A tourist jumps in San Marco square in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Gondola sail in a canal in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

A man walks as people stand on a water bus "Vaporetto" in Venice Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Tourists walk in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Tourists walk in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Tourists visit in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

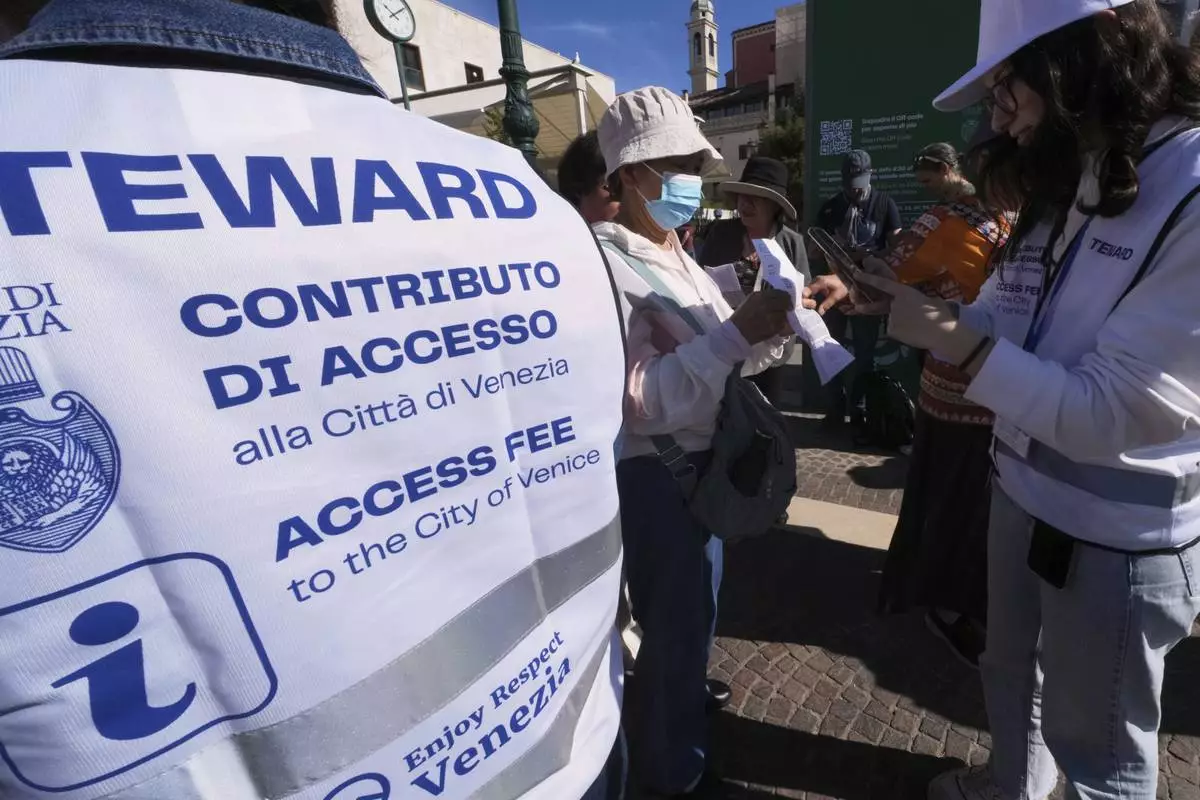

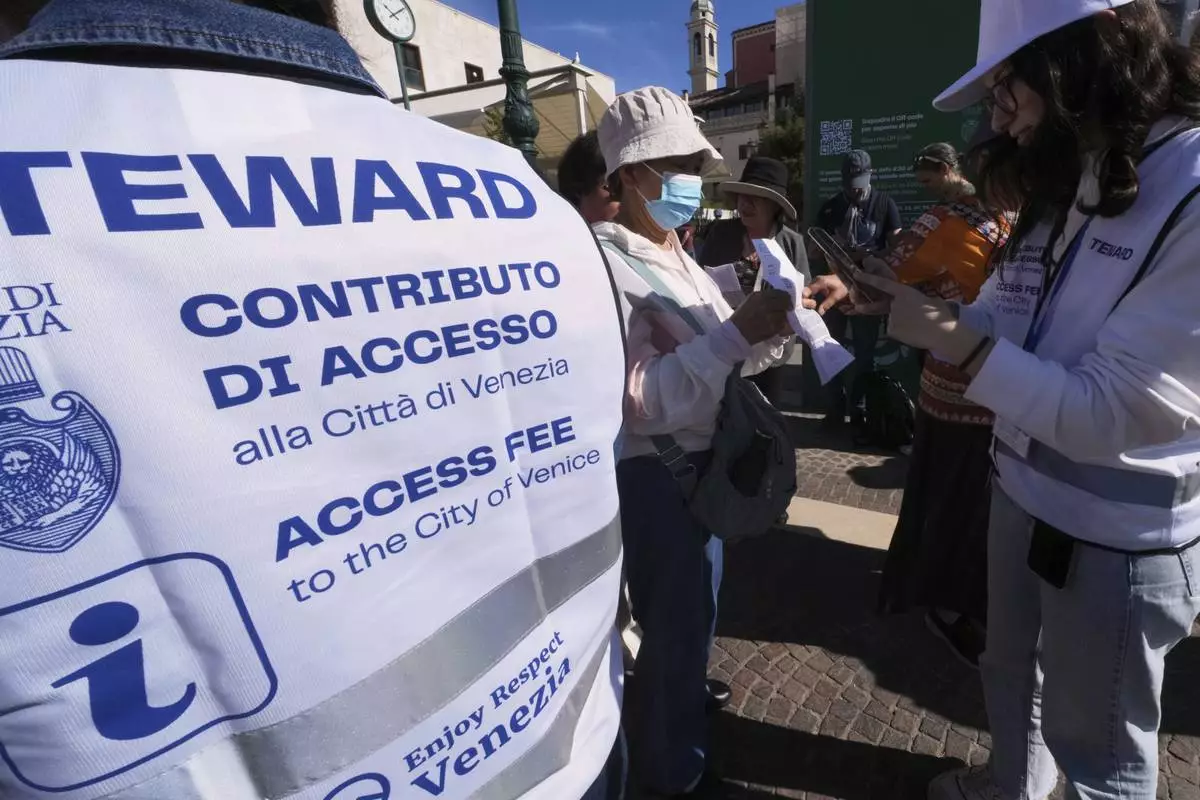

Stewards check tourists' QR codes outside the main train station in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, as the city for a second year is charging day-trippers an arrivals tax. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Stewards check tourists' QR codes outside the main train station in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, as the city for a second year is charging day-trippers an arrivals tax. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

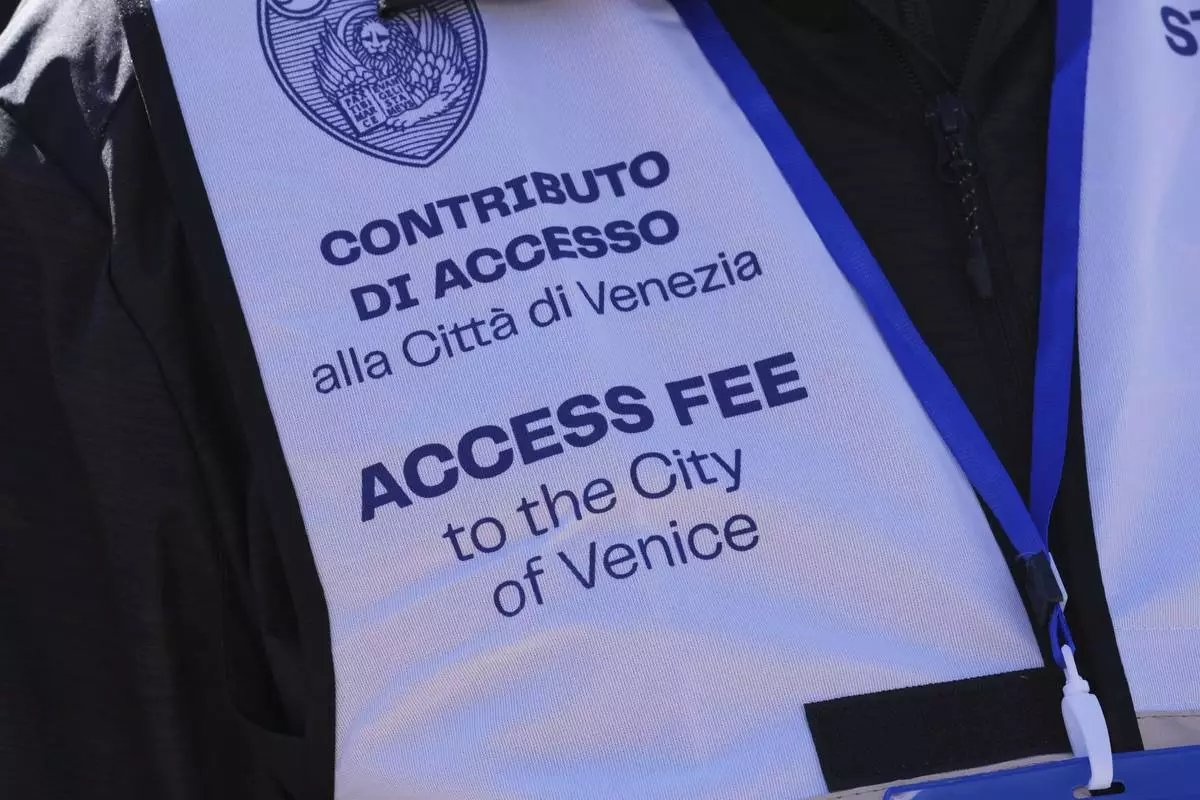

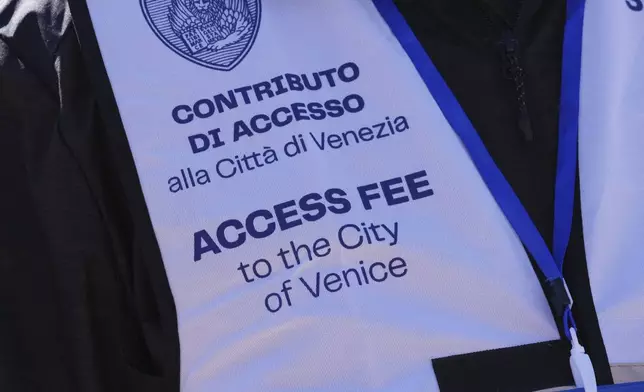

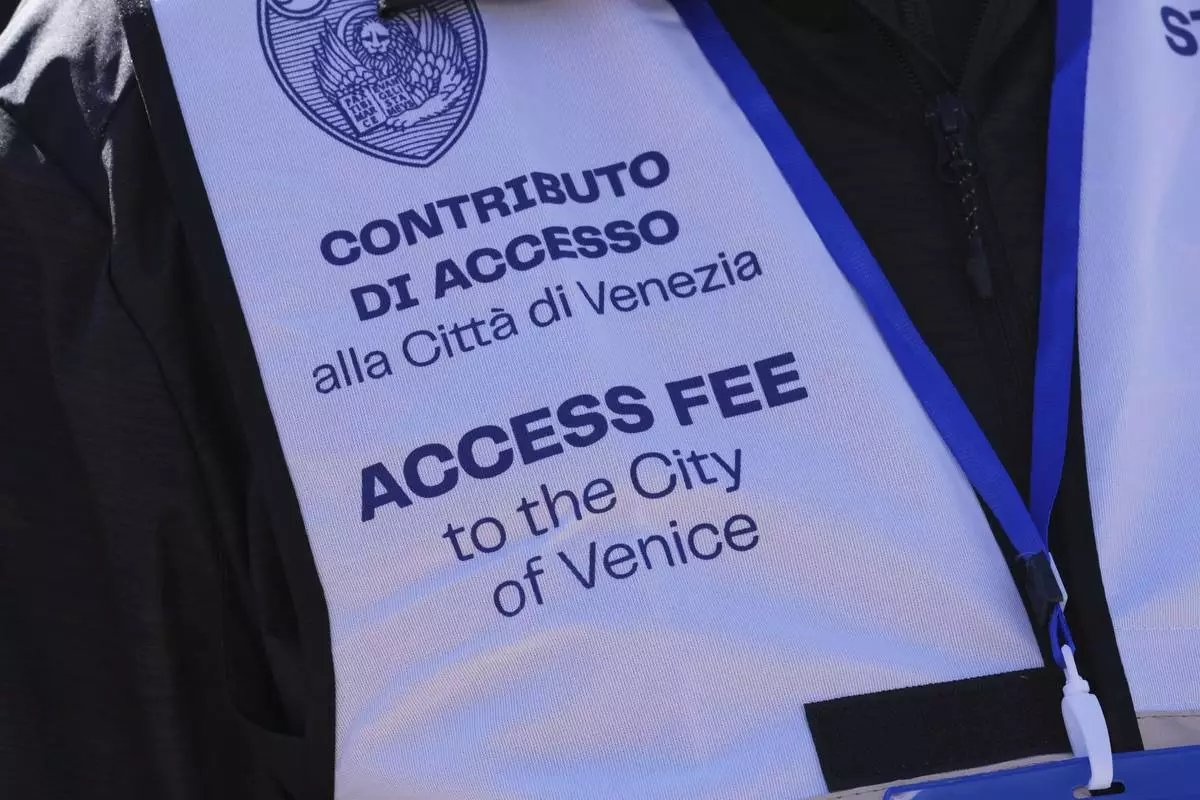

A steward's gilet states an arrival tax fee for tourists visiting Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Stewards check tourists' QR codes outside the main train station in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, as the city for a second year is charging day-trippers an arrivals tax. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Stewards check tourists' QR codes outside the main train station in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, as the city for a second year is charging day-trippers an arrivals tax. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Stewards check tourists' QR codes outside the main train station in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, as the city for a second year is charging day-trippers an arrivals tax. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Stewards check tourists' QR codes outside the main train station in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, as the city for a second year is charging day-trippers an arrivals tax. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Here’s a look at Venice’s battle with overtourism by the numbers:

The fee charged to visitors who are not overnighting in Venice to enter its historic center during the second year of the day-tripper tax. Visitors who download a QR code at least three days in advance will pay 5 euros ($5.69) — the same amount charged last year throughout the pilot program. But those who make last-minute plans pay double. The QR code is required from 8:30 a.m. until 4 p.m. and is checked at entry points to the city, including the Santa Lucia train station, the Piazzale Roma bus depot and the Tronchetto parking garage.

The number of days this year that day visitors to Venice will be charged a fee to enter the historic center. They include mostly weekends and holidays from April 18 to July 27. That is up from 29 last year. The new calendar covers entire weeks over key holidays and extends the weekend period to include Fridays.

That is the amount Venice took in during a 2024 pilot program for the tax. The city's top budget official, Michele Zuin, said last year the running costs for the new system ran to 2.7 million euros, overshooting the total fees collected. This year, Zuin projects a surplus of about 1 million euros to 1.5 million euros, which will be used to offset the cost of trash collection and other services for residents.

The number of day-trippers who paid the tax in 2024. Officials said that 12,744 day-trippers paid to enter the city on Friday — 7,173 at the higher 10-euro rate. They were among the 77,000 who have registered so far to enter the city this year. Another 117,000 have registered for exemptions, which apply to anyone born in Venice, those paying property taxes in the city, studying or working in the historic center, or living in the wider Veneto region, among others.

The average number of daily visitors on the first 11 days of 2024 that Venice charged day-trippers. That's about 10,000 people more than the number of tourists recorded on each of the three important holidays during the previous year. City council member Giovanni Andrea Martini, an opponent of the measure, said the figures show the project has not deterred visitors.

The number of official residents in Venice’s historic center composed of over 100 islands connected by footbridges and traversed by its famed canals. The population peaked at 174,000 in 1951, when Venice was home to thriving industries. The number shrank during Italy's postwar economic boom as residents moved to the mainland for more modern housing — including indoor plumbing which was lacking in Venice. It has been shrinking dramatically over recent decades as local industry lost traction, families sought mainland conveniences and housing prices rose. Activists also blame the “mono-culture” of tourism, which they say has emptied the city of basic services like shops for everyday goods and medical care.

The number of beds for tourists in Venice’s historic center, including 12,627 in the less regulated short-term rental market, according to April data from the Ocio housing activist group. The number of tourist beds surpassed the number of permanent residents in 2023, according to Ocio's monitor. Anyone staying in a hotel within the city limits, including on the mainland districts of Mestre and Marghera, pays a lodging tax and is therefore exempt from the day-tripper tax.

The number of annual arrivals of both day-trippers and overnight guests roughly confirmed by cellphone data tracked from a Smart Control Room since 2020, according to city officials.

Tourists take pictures next Rialto Bridge "Ponte di Rialto" in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

A taxi sails under the Rialto Bridge "Ponte di Rialto" in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Tourists take pictures in San Marco square in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Tourists take a break in San Marco square in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

People walk in San Marco square in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Tourists take pictures on Rialto Bridge "Ponte di Rialto" in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Tourists take pictures on Rialto Bridge "Ponte di Rialto" in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

A tourist jumps in San Marco square in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Gondola sail in a canal in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

A man walks as people stand on a water bus "Vaporetto" in Venice Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Tourists walk in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Tourists walk in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Tourists visit in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, Venice on Friday launches for a second year a pilot program to charge day-trippers an entrance fee. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Stewards check tourists' QR codes outside the main train station in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, as the city for a second year is charging day-trippers an arrivals tax. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Stewards check tourists' QR codes outside the main train station in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, as the city for a second year is charging day-trippers an arrivals tax. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

A steward's gilet states an arrival tax fee for tourists visiting Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Stewards check tourists' QR codes outside the main train station in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, as the city for a second year is charging day-trippers an arrivals tax. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Stewards check tourists' QR codes outside the main train station in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, as the city for a second year is charging day-trippers an arrivals tax. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Stewards check tourists' QR codes outside the main train station in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, as the city for a second year is charging day-trippers an arrivals tax. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

Stewards check tourists' QR codes outside the main train station in Venice, Italy, Friday, April 18, 2025, as the city for a second year is charging day-trippers an arrivals tax. (AP Photo/Antonio Calanni)

MONTEVIDEO, Uruguay (AP) — Former Uruguayan President José Mujica, a onetime Marxist guerilla and flower farmer whose radical brand of democracy, plain-spoken philosophy and simple lifestyle fascinated people around the world, has died. He was 89.

Uruguay's left-wing president, Yamandú Orsi, announced his death, which came four months after Mujica decided to forgo further medical treatment for esophageal cancer and enter hospice care at his three-room ranch house on the outskirts of Montevideo, Uruguay’s capital.

“President, activist, guide and leader,” Orsi wrote of his longtime political mentor before heading to Mujica's home to pay his respects. “Thank you for everything you gave us.”

Mujica had been under treatment for cancer of the esophagus since his diagnosis last spring. Radiation eliminated much of the tumor but soon Mujica’s autoimmune disease complicated his recovery.

In January, Mujica’s doctor announced that the cancer in his esophagus had returned and spread to his liver. In recent days, “he knew that he was in his final hours,” said Fernando Pereira, the president of Mujica's left-wing Broad Front party who visited the ailing ex-leader last week.

As leader of a violent leftist guerrilla group in the 1960s known as the Tupamaros, Mujica robbed banks, planted bombs and abducted businessmen and politicians on Montevideo’s streets in hopes of provoking a popular uprising that would lead to a Cuban-style socialist Uruguay.

A brutal counterinsurgency and ensuing right-wing military dictatorship that ruled Uruguay between 1973 and 1985 sent him to prison for nearly 15 years, 10 of which he spent in solitary confinement.

During his 2010-2015 presidency, Mujica, widely known as “Pepe,” oversaw the transformation of his small South American nation into one of the world’s healthiest and most socially liberal democracies. He earned admiration at home and cult status abroad for legalizing marijuana and same-sex marriage, enacting the region’s first sweeping abortion rights law and establishing Uruguay as a leader in alternative energy.

Rejecting the pomp and circumstance of the presidency, he drove a light blue beat-up 1987 Volkswagen Beetle, wore rumpled cardigan sweaters and sandals with socks and lived in a tin-roof house outside Montevideo, where for decades he tended to chrysanthemums for sale in local markets.

“This is the tragedy of life, on the one hand it’s beautiful, but it ends,” Mujica told The Associated Press in a wide-ranging Oct. 2023 interview from his farmhouse. “Therefore, paradise is here. As is hell.”

As the Uruguayan government declared three days of national mourning, tributes poured in from presidents and ordinary people around the world. The first to share remembrances were allied leaders who recalled not only Mujica's accomplishments but also his hallowed status as one of the last surviving lions of the now-receding Latin American left that peaked two decades ago.

Colombian President Gustavo Petro praised Mujica as a “great revolutionary." Bolivia’s former socialist president, Evo Morales said that he “and all of Latin America" are in mourning. Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum called Mujica “an example for Latin America and the entire world.” Brazil's Foreign Ministry described him as “one of the most important humanists of our time.”

Chile's leftist President Gabriel Boric paid tribute to Mujica's efforts to combat social inequality.

“If you left us anything, it was the unquenchable hope that things can be done better,” he wrote. “The unwavering conviction that as long as our hearts beat and there is injustice in the world, it’s worth continuing to fight.”

Mujica never attended university and didn’t finish high school. But politics piqued his interest as early as adolescence, when the young flower farmer joined the progressive wing of the conservative National Party, one of the two main parties in Uruguay. His pivot to urban guerrilla warfare came in the 1960s, as leftist struggles swept the region in the wake of the Cuban Revolution.

He and other student and labor radicals launched the Tupamaros National Liberation Movement, which quickly gained notoriety for its Robin Hood-style exploits aimed at installing a revolutionary government.

By 1970 the government cracked down, and the Tupamaros responded with violence, planting bombs in upscale neighborhoods and attacking casinos and other civilian targets, killing more than 30 people.

Mujica was shot six times in a firefight with police in a bar. He helped stage a prison break and twice escaped custody. But in 1973 the military seized power, unleashing a reign of terror upon the population that resulted in the forced disappearance of some 200 Uruguayans and the imprisonment of thousands.

During his time in prison, he endured torture and long stretches in solitary confinement, often in a hole in the ground.

After power returned to civilians in 1985, Mujica left prison under an amnesty that covered the crimes of the dictators and their guerrilla opponents. He entered mainstream politics with the Broad Front, a coalition of radical leftists and centrist social democrats.

Rapidly rising through the party ranks, Mujica charmed the country with his low-key way of living and penchant for speaking his mind. In 2005 he entered government with the Broad Front as an agricultural minister. Just four years later he was Uruguay’s 40th president, elected with 52% of the vote.

His wife, Lucía Topolansky, a former co-revolutionary guerrilla member who was also imprisoned before becoming a prominent politician, bestowed the presidential sash on Mujica at his inauguration — as is custom for the senator who had received the most votes. They married in 2005 and had no children.

“I’ve been with him for over 40 years, and I’ll be with him until the end,” she told a local radio station Sunday as Mujica's condition deteriorated.

Pepe’s bracingly modest and spontaneous style as president — distributing pamphlets in the streets against machismo culture, lunching in Montevideo bars — made him a populist folk hero and token of global fascination.

“They made me seem like some impoverished president, but they were the poor ones ... imagine if you have to live in that four-story government house just to have tea,” he told the AP of his decision to shun the presidential palace.

Over his years in power, Mujica presided over comfortable economic growth, rising wages and falling poverty. In speeches, he pushed Uruguayans to reject consumerism and embrace their nation’s tradition of simplicity.

Under his watch, the small nation became known worldwide for the strength of its institutions and the civility of its politics — rare features most recently on display during Uruguay’s 2024 presidential vote that vaulted Orsi, Mujica’s moderate protégé, to power.

Mujica's greatest innovations came on social issues. During his term, Uruguay became the first country in South America to legalize abortion for the first trimester and the first in the world to legalize the production, distribution and sale of marijuana. His government also legalized same-sex marriage, burnishing Uruguay’s progressive image in the predominantly Catholic region.

Mujica’s government also powered a green energy revolution that transformed Uruguay into one of the world’s most environmentally friendly nations. Today the country generates 98% of its electricity from biomass, solar and wind energy.

His tenure was also not without controversy. The opposition complained of rising crime and a swollen fiscal deficit that forced his successor to raise taxes.

Some world leaders disapproved of his disdain for the established order. Conservative Uruguayans voiced outrage over his progressive policies.

Still, Mujica ended his tenure with a 60% approval rating. Ineligible to seek re-election because of a ban on consecutive terms, he continued to wield influence at home as an elected senator and abroad as a trailblazer and sage.

Even so, his humility defined him until the end.

“They ask you: ‘How do you want to be remembered?’ Vanity of vanities!” he exclaimed to the AP. “Memory is a historical thing. ... Years go by. Not even the dust remains.”

DeBre reported from Buenos Aires, Argentina. Associated Press writers Leonardo Haberkorn in Montevideo, Uruguay, and Nayara Batschke in Santiago, Chile, contributed to this report.

FILE - Uruguay's President Jose Mujica, left, and his wife Lucia Topolansky attend a flag ceremony in Montevideo, Uruguay, Feb. 27, 2015. (AP Photo/Matilde Campodonico, File)

FILE - Presidential candidate Jose Mujica drinks mate during a closing campaign rally in Pando, Uruguay, Oct. 22, 2009. (AP Photo/Matilde Campodonico, File)

FILE - Jose "Pepe" Mujica, 74, presidential hopeful for the governing Broad Front leftist coalition, stands in a tractor on his flower farm after voting in Uruguay's general elections, on the outskirts of Montevideo, Oct. 25, 2009. (AP Photo/Matilde Campodonico, File)

FILE - Uruguay's President Jose Mujica poses for a photo with his dog, Manuela, at his home on the outskirts of Montevideo, Uruguay, May 2, 2014. (AP Photo/Matilde Campodonico, File)

FILE - TO HOLD - Uruguay's former President Jose Mujica arrives to cast his vote in Montevideo, Uruguay, Oct. 26, 2014. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko, File)